Perinatal Depression Research Trends in Canada: A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Perinatal Depression Research Trends in Canada: A Bibliometric Analysis

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Data Collection

2.3. Data Validation and Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometric Data

3.2. Country Affiliations

3.3. Canadian Institutional Affiliations

3.4. Journals

3.5. Publications

3.6. Authors

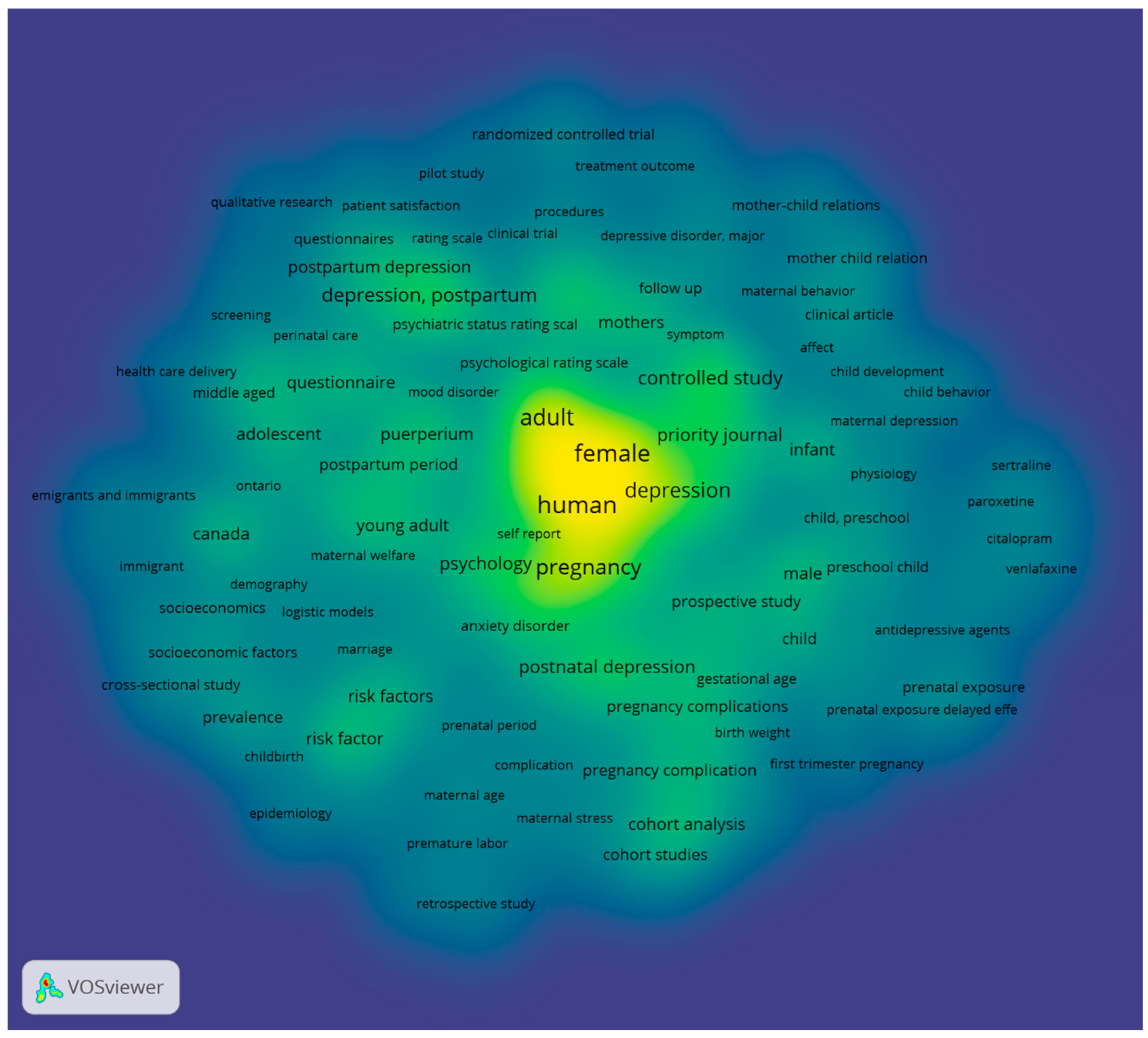

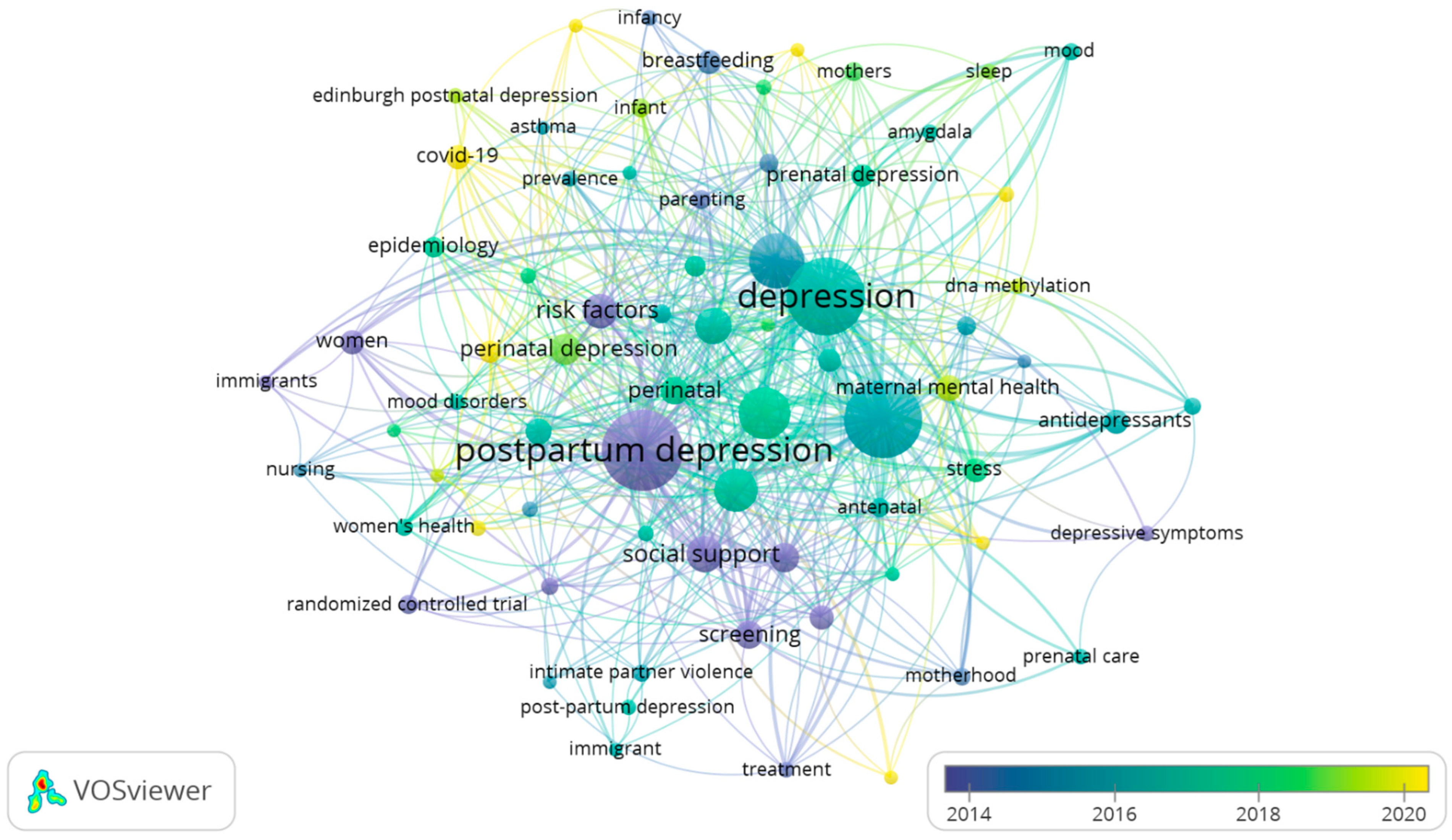

3.7. Keywords

- The largest cluster (red) contains 46 keywords related to “diagnostic labels,” including terms like postpartum depression, anxiety disorder, postpartum period, puerperium, and mood disorder. It also includes “psychometric terms” such as controlled study, questionnaire, screening, and psychological rating scale.

- The second cluster (green) consists of 45 keywords related to “risk factors and social aspects of research,” including terms such as adolescent, mental health, psychology, prenatal care, social support, and socioeconomics.

- The third cluster (blue) includes 40 keywords pertaining to “depression outcomes and treatment” such as prenatal exposure, mother child relation (s), mood, affect, maternal behaviour, priority journal, and antidepressant medications.

- The fourth cluster (yellow) and the fifth cluster (purple), with 31 and 6 keywords, respectively, are centred on “research methods and outcomes.” These include terms such as complications, stress, anxiety, disease association, gestational age, premature labour, cohort analysis, and longitudinal studies.

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; DSM-V: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alhusen, J.L.; Alvarez, C. Perinatal depression: A clinical update. Nurse Pract. 2016, 41, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; McCabe, J.E. Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart-Parrigon, K.; Stuart, S. Perinatal Depression: An Update and Overview. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagher, R.K.; Bruckheim, H.E.; Colpe, L.J.; Edwards, E.; White, D.B. Perinatal Depression: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Womens Health 2021, 30, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woody, C.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Siskind, D.J.; Whiteford, H.A.; Harris, M.G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 219, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Maternal Mental Health in Canada (No. 11-627-M). 2019. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2019041-eng.htm (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). What Mothers Say: The Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey; PHAC: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2009. Available online: http://www.publichealth.gc.ca/mes (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Field, T. Prenatal Depression Risk Factors, Developmental Effects and Interventions: A Review. J. Pregnancy Child Health 2017, 4, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, C.A.; Gold, K.J.; Flynn, H.A.; Yoo, H.; Marcus, S.M.; Davis, M.M. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J.H. Perinatal depression and infant mental health. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yawn, B.P.; Pace, W.; Wollan, P.C.; Bertram, S.; Kurland, M.; Graham, D.; Dietrich, A. Concordance of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to assess increased risk of depression among postpartum women. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2009, 22, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). Assessment and Interventions for Perinatal Depression; RNAO: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2018; Available online: https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/assessment-and-interventions-perinatal-depression (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Eustis, E.H.; Ernst, S.; Sutton, K.; Battle, C.L. Innovations in the Treatment of Perinatal Depression: The Role of Yoga and Physical Activity Interventions During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluxton-Keller, F.; Bruce, M.L. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions in the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, Z.; Rosen, B.; Howlett, A.; Anderson, M.; Herman, D. Interventions for paternal perinatal depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.W.; Denison, F.C.; Hor, K.; Reynolds, R.M. Web-based interventions for prevention and treatment of perinatal mood disorders: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yue, S.W.; Xu, J.; Qiao, J.; Redding, S.R.; Ouyang, Y.Q. Effectiveness of Internet-based psychological interventions for treating perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 3087–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettman, D.; O’Mahen, H.; Blomberg, O.; Svanberg, A.S.; von Essen, L.; Woodford, J. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy-based interventions for maternal perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suradom, C.; Suttajit, S.; Oon-arom, A.; Maneeton, B.; Srisurapanont, M. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (n-3 PUFA) supplementation for prevention and treatment of perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2021, 75, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgate, V.; Manchanda, T.; Maxwell, M. Women’s experiences of care and treatment preferences for perinatal depression: A systematic review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2023, 26, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care. Depression During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. 2022. Available online: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines/depression-during-pregnancy-and-the-postpartum-period/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Centre of Perinatal Excellence. Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline. 2023. Available online: https://www.cope.org.au/uploads/images/Health-professionals/COPE_2023_Perinatal_Mental_Health_Practice_Guideline.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- National Health Service (NHS). NHS Improvement, National Collaboration Centre for Mental Health. The Perinatal Mental Health Care Pathways. 2018. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192/resources/the-perinatal-mental-health-care-pathways-pdf-4844068237 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ali, U.; Waqas, A.; Ayub, M. Research trends and geographical contribution in the field of perinatal mental health: A bibliometric analysis from 1900 to 2020. Women’s Health Rep. 2022, 3, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Song, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D. Bibliometrics and Visual Analysis of the Research Status and Trends of Postpartum Depression From 2000 to 2020. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 665181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dol, J.; Dennis, C.L.; Campbell-Yeo, M.; Leahy-Warren, P. Bibliometric analysis of published articles on perinatal depression from 1920 to 2020. Birth 2024, 51, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Shan, Y. Hot spots and frontiers of postpartum depression research in the past 5 years: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 901668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.L.; Singla, D.R.; Brown, H.K.; Savel, K.; Clark, C.T.; Grigoriadis, S.; Vigod, S.N. Postpartum Depression: A Clinical Review of Impact and Current Treatment Solutions. Drugs 2024, 84, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dol, J.; Richardson, B.; Murphy, G.T.; Aston, M.; McMillan, D.; Campbell-Yeo, M. Impact of mobile health interventions during the perinatal period on maternal psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, N.L.; Dennis, C.L.; Cosic, N.; Linder, J. The effect of perinatal depression treatment for mothers on parenting and child development: A systematic review. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 928–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigod, S.N.; Villegas, L.; Dennis, C.L.; Ross, L.E. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: A systematic review. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010, 117, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, R. Digital journalism: 25 years of research. Review article. El Prof. De La Inf. 2019, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonzo, P.M.; Sakraida, T.J.; Hastings-Tolsma, M. Bibliometrics: Visualizing the Impact of Nursing Research. Online J. Nurs. Inform. 2014, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, O.; Kocaman, R.; Kanbach, D.K. How to design bibliometric research: An overview and a framework proposal. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrino, J.; Portero de la Cruz, S. A worldwide bibliometric analysis of published literature on workplace violence in healthcare personnel. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramo, G.; Cicero, T.; D’Angelo, C.A. Assessing the varying level of impact measurement accuracy as a function of the citation window length. J. Informetr. 2011, 5, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual: Version 1.6.20. 2023. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.20.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Oberlander, T.F.; Weinberg, J.; Papsdorf, M.; Grunau, R.; Misri, S.; Devlin, A.M. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics 2008, 3, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebel, C.; MacKinnon, A.; Bagshawe, M.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Giesbrecht, G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotlib, I.H.; Whiffen, V.E.; Mount, J.H.; Milne, K.; Cordy, N.I. Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 57, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergink, V.; Kooistra, L.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.P.; Wijnen, H.; Bunevicius, R.; Van Baar, A.; Pop, V. Validation of the Edinburgh Depression Scale during pregnancy. J. Psychosom. Res. 2011, 70, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Duan, C.; Li, C.; Fan, J.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Li, X. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 240.e1–240.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, D.R.; O’HARA, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Gorman, L.L.; Larsen, K.E.; Coy, K.C. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother–child relationship. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.J.; Jensen, A.B.; Freeman, L.; Khalife, N.; O’Connor, T.G.; Glover, V. Maternal prenatal anxiety and downregulation of placental 11β-HSD2. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.J.; Glover, V.; Barker, E.D.; O’connor, T.G. The persisting effect of maternal mood in pregnancy on childhood psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, A.M.; Brain, U.; Austin, J.; Oberlander, T.F. Prenatal exposure to maternal depressed mood and the MTHFR C677T variant affect SLC6A4 methylation in infants at birth. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.-L.; Hodnett, E.; Kenton, L.; Weston, J.; Zupancic, J.; Stewart, D.E.; Kiss, A. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: Multisite randomised controlled trial. Bmj 2009, 338, a3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, E.E.; Joyce, K.M.; Delaquis, C.P.; Reynolds, K.; Protudjer, J.L.; Roos, L.E. Maternal psychological distress & mental health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotlib, I.H.; Whiffen, V.E.; Wallace, P.M.; Mount, J.H. Prospective investigation of postpartum depression: Factors involved in onset and recovery. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.L.; Ross, L. Relationships among infant sleep patterns, maternal fatigue, and development of depressive symptomatology. Birth 2005, 32, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, D.; Larouche, J.; Dritsa, M.; Brender, W. Psychosocial correlates of prepartum and postpartum depressed mood. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 59, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, L.E.; Evans, S.G.; Sellers, E.; Romach, M. Measurement issues in postpartum depression part 1: Anxiety as a feature of postpartum depression. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2003, 6, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLearn, K.T.; Minkovitz, C.S.; Strobino, D.M.; Marks, E.; Hou, W. Maternal depressive symptoms at 2 to 4 months post partum and early parenting practices. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006, 160, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiffen, V.E.; Gotlib, I.H. Infants of postpartum depressed mothers: Temperament and cognitive status. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1989, 98, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukhris, T.; Sheehy, O.; Mottron, L.; Bérard, A. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Strat, Y.; Dubertret, C.; Le Foll, B. Prevalence and correlates of major depressive episode in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 135, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.L.; Janssen, P.A.; Singer, J. Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 110, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelkowitz, P.; Tamara, H.M. Screening for post-partum depression in a community sample. Can. J. Psychiatry 1995, 40, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rifkin-Graboi, A.; Bai, J.; Chen, H.; Hameed, W.B.r.; Sim, L.W.; Tint, M.T.; Leutscher-Broekman, B.; Chong, Y.-S.; Gluckman, P.D.; Fortier, M.V. Prenatal maternal depression associates with microstructure of right amygdala in neonates at birth. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanes, A.; Kuk, J.L.; Tamim, H. Prevalence and characteristics of postpartum depression symptomatology among Canadian women: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, A.; Anh, T.T.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Rifkin-Graboi, A.; Broekman, B.F.; Kwek, K.; Saw, S.M.; Chong, Y.S.; Gluckman, P.D. Prenatal maternal depression alters amygdala functional connectivity in 6-month-old infants. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.E.; Gagnon, A.; Saucier, J.-F.; Wahoush, O.; Dougherty, G. Postpartum Depression Symptoms in Newcomers. Can. J. Psychiatry 2008, 53, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.-L.; Brown, H.K.; Brennenstuhl, S. The Postpartum Partner Support Scale: Development, psychometric assessment, and predictive validity in a Canadian prospective cohort. Midwifery 2017, 54, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.-L. Can we identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale? J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 78, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.-L. The Effect of Peer Support on Postpartum Depression: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Can. J. Psychiatry 2003, 48, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lariviere, V.; Grant, J. Bibliometric Analysis of Mental Health Research: 1980–2008. Rand Health Q. 2017, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Top 10 Authors, Journals, and Research Areas | Number of Publications (% of Total Publications) |

|---|---|

| Canadian Authors | |

| 57 (7.47%) |

| 39 (5.11%) |

| 38 (4.98%) |

| 37 (4.84%) |

| 31 (4.06%) |

| 30 (3.93%) |

| 29 (3.80%) |

| 22 (2.88%) |

| 22 (2.88%) |

| 21 (2.75%) 21 (2.75%) |

| Journals (not limited to Canada) | |

| 57 (7.47%) |

| 40 (5.24%) |

| 27 (3.54%) |

| 21(2.75%) |

| 17 (2.23%) |

| 16 (2.10%) |

| 15 (1.97%) |

| 10 (1.31%) |

| 10 (1.31%) |

Translational Psychiatry | 9 (1.18%) 9 (1.18%) 9 (1.18%) |

| Scopus Research Areas | |

| 55.8% |

| 14.30% |

| 8.10% |

| 6.70% |

| 3.50% |

| 3.10% |

| 2.00% |

| 1.60% |

| 1.30% |

| 1.20% |

| Rank | Journal | Publications | Cluster Number | Links | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Archives of Women’s Mental Health | 57 | 5 | 48 | 128 |

| 2 | Journal of Affective Disorders | 40 | 4 | 50 | 106 |

| 3 | BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth | 27 | 5 | 31 | 56 |

| 4 | Canadian Journal of Psychiatry | 21 | 2 | 51 | 129 |

| 5 | PLOS One | 17 | 1 | 19 | 25 |

| 6 | Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | 16 | 3 | 22 | 38 |

| 7 | International Journal of Environment Research and Public Health | 15 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| 8 | JOGNN—Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing | 10 | 5 | 18 | 25 |

| 9 | Journal of Women’s Health | 10 | 6 | 17 | 23 |

| 10 | BMJ Open | 9 | 4 | 11 | 12 |

| Maternal and Child Health Journal | 9 | 3 | 16 | 23 | |

| Translational Psychiatry | 9 | 1 | 16 | 37 |

| Authors | Publication | Journal Title | Publication Year | Total Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oberlander T.F., Weinberg J., Papsdorf M., Grunau R., Misri S., Devlin A.M. [41] | Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses | Epigenetics | 2008 | 1118 |

| Lebel C., MacKinnon A., Bagshawe M., Tomfohr-Madsen L., Giesbrecht G. [42] | Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic | Journal of Affective Disorders | 2020 | 541 |

| Gotlib I.H., Whiffen V.E., Mount J.H., Milne K., Cordy N.I. [43] | Prevalence Rates and Demographic Characteristics Associated With Depression in Pregnancy and the Postpartum | Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology | 1989 | 470 |

| Bergink V., Kooistra L., Lambregtse-van den Berg M.P., Wijnen H., Bunevicius R., van Baar A., Pop V. [44] | Validation of the Edinburgh Depression Scale during pregnancy | Journal of Psychosomatic Research | 2011 | 418 |

| Wu Y., Zhang C., Liu H., Duan C., Li C., Fan J., Li H., Chen L., Xu H., Li X., Guo Y., Wang Y., Li X., Li J., Zhang T., You Y., Li H., Yang S., Tao X., Xu Y., Lao H., Wen M., Zhou Y., Wang J., Chen Y., Meng D., Zhai J., Ye Y., Zhong Q., Yang X., Zhang D., Zhang J., Wu X., Chen W., Dennis C.-L., Huang H.-F. [45] | Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China | American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology | 2020 | 414 |

| Forman D.R., O’Hara M.W., Stuart S., Gorman L.L., Larsen K.E., Coy K.C. [46] | Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship | Development and Psychopathology | 2007 | 367 |

| O’Donnell K.J., Bugge Jensen A., Freeman L., Khalife N., O’Connor T.G., Glover V. [47] | Maternal prenatal anxiety and downregulation of placental 11β-HSD2 | Psychoneuroendocrinology | 2012 | 346 |

| O’Donnell K.J., Glover V., Barker E.D., O’Connor T.G. [48] | The persisting effect of maternal mood in pregnancy on childhood psychopathology | Development and Psychopathology | 2014 | 293 |

| Devlin A.M., Brain U., Austin J., Oberlander T.F. [49] | Prenatal exposure to maternal depressed mood and the MTHFR C677T variant affect SLC6A4 methylation in infants at birth | PLoS ONE | 2010 | 255 |

| Dennis C.-L., Hodnett E., Kenton L., Weston J., Zupancic J., Stewart D.E., Kiss A. [50] | Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: Multisite randomised controlled trial | BMJ (Online) | 2009 | 248 |

| Cameron E.E., Joyce K.M., Delaquis C.P., Reynolds K., Protudjer J.L.P., Roos L.E. [51] | Maternal psychological distress & mental health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic | Journal of Affective Disorders | 2020 | 246 |

| Gotlib I.H., Whiffen V.E., Wallace P.M., Mount J.H. [52] | Prospective Investigation of Postpartum Depression: Factors Involved in Onset and Recovery | Journal of Abnormal Psychology | 1991 | 246 |

| Dennis C.L., Ross L. [53] | Relationships among infant sleep patterns, maternal fatigue, and development of depressive symptomatology. | Birth (Berkeley, Calif.) | 2005 | 244 |

| Da Costa D., Larouche J., Dritsa M., Brender W. [54] | Psychosocial correlates of prepartum and postpartum depressed mood | Journal of Affective Disorders | 2000 | 244 |

| Ross L.E., Evans S.E.G., Sellers E.M., Romach M.K. [55] | Measurement issues in postpartum depression part 1: Anxiety as a feature of postpartum depression | Archives of Women’s Mental Health | 2003 | 232 |

| McLearn K.T., Minkovitz C.S., Strobino D.M., Marks E., Hou W. [56] | Maternal depressive symptoms at 2 to 4 months post partum and early parenting practices | Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine | 2006 | 228 |

| Whiffen V.E., Gotlib I.H. [57] | Infants of Postpartum Depressed Mothers: Temperament and Cognitive Status | Journal of Abnormal Psychology | 1989 | 225 |

| Boukhris T., Sheehy O., Mottron L., Berard A. [58] | Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder in children | JAMA Pediatrics | 2016 | 215 |

| Le Strat Y., Dubertret C., Le Foll B. [59] | Prevalence and correlates of major depressive episode in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States | Journal of Affective Disorders | 2011 | 201 |

| Dennis C.-L.E., Janssen P.A., Singer J. [60] | Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period | Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica | 2004 | 200 |

| Rank | Publication | Citations | Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dennis, C.-L. E, Janssen, P. A. [60] | 200 | 26 |

| 2 | Bergink et al. [44] | 418 | 25 |

| 3 | Zelkowitz, P. & Milet, T. H. [61] | 126 | 25 |

| 4 | Rifkin-Graboi, A., Bai, J., Chen, H., Hameed, W. B., Sim, L. W., Tint, M. T., Leutscher-Broekman, B., Chong, Y., Gluckamn, P. D., Fortier, M. V., Meaney, M. J., & Qiu, A. [62] | 190 | 22 |

| 5 | Lanes, A., Kuk, J. L., & Tamim, H. [63] | 124 | 19 |

| 6 | Qiu, A., Anh, T. T., Li, Y., Chen, H., Rifkin-Graboi, A., Broekman, B. F. P., Kwek, K., Saw, S., Chong, Y., Gluckamn P. D., Fortier, M.V., & Meaney, M. J. [64] | 199 | 16 |

| 7 | Oberlander et al. [41] | 1118 | 16 |

| 8 | Stewart, D. E., Gagon, A., Sauciet, J., Wahoush, O., & Dougherty, G. [65] | 123 | 16 |

| 9 | Gotlib, I. H., Whiffern, V. E., Mount, J. H., Milne, K., & Cordy, N. I. [43] | 470 | 16 |

| 10 | Dennis, C.-L., Brown, H. K., & Brennenstuhl, S. [66] | 17 | 14 |

| Dennis, C.-L. [67] | 161 | 14 | |

| Dennis, C.-L. [68] | 158 | 14 |

| Rank | Keyword | Cluster | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human | 1 | 718 | 15,046 |

| 2 | Female | 1 | 714 | 15,012 |

| 3 | Article | 1 | 614 | 13,490 |

| 4 | Humans | 2 | 611 | 13,603 |

| 5 | Adult | 1 | 605 | 13,144 |

| 6 | Pregnancy | 4 | 481 | 10,687 |

| 7 | Depression | 3 | 385 | 8519 |

| 8 | Major Clinical Study | 4 | 367 | 8594 |

| 9 | Controlled study | 1 | 329 | 7388 |

| 10 | Depression, postpartum | 1 | 327 | 7135 |

| 11 | Postnatal depression | 4 | 281 | 6294 |

| 12 | Puerperal depression | 1 | 266 | 5546 |

| 13 | Priority journal | 3 | 261 | 6129 |

| 14 | Psychology | 2 | 243 | 5786 |

| 15 | Edinburgh postnatal depression scale | 1 | 212 | 4946 |

| 16 | Risk factor | 2 | 205 | 4927 |

| 17 | Male | 3 | 197 | 4694 |

| 18 | Puerperium | 1 | 193 | 4387 |

| 19 | Cohort analysis | 4 | 188 | 4678 |

| 20 | Mothers | 3 | 187 | 4418 |

| 21 | Anxiety | 5 | 174 | 4089 |

| 22 | Mother | 3 | 170 | 4053 |

| 23 | Young adult | 2 | 167 | 3981 |

| 24 | Canada | 2 | 165 | 3731 |

| 25 | Questionnaire | 1 | 163 | 3854 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolak, J.E.; Letourneau, N.; Hayden, K.A. Perinatal Depression Research Trends in Canada: A Bibliometric Analysis. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030086

Wolak JE, Letourneau N, Hayden KA. Perinatal Depression Research Trends in Canada: A Bibliometric Analysis. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030086

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolak, Julia E., Nicole Letourneau, and K. Alix Hayden. 2025. "Perinatal Depression Research Trends in Canada: A Bibliometric Analysis" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030086

APA StyleWolak, J. E., Letourneau, N., & Hayden, K. A. (2025). Perinatal Depression Research Trends in Canada: A Bibliometric Analysis. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030086