Intervention Effects of a School-Based Smoking Cessation Program on Nicotine Dependence and Mental Health Among Korean Adolescent Smokers: The Experience New Days (END) Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

Experience New Days (END) Program

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

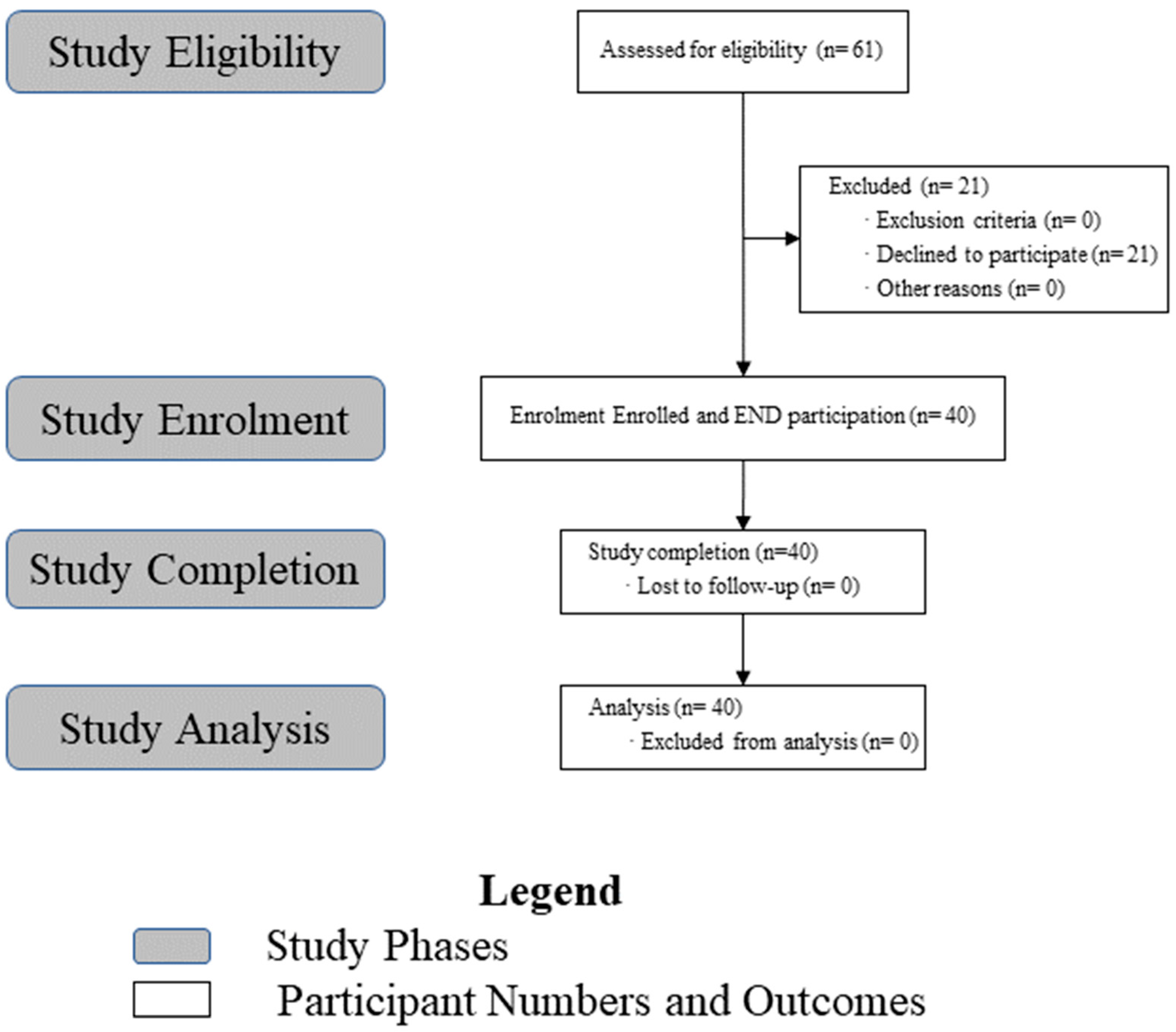

2.2. Participants

2.3. Intervention Program

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)

2.4.2. Cigarette Dependence Scale-12 (CDS-12)

2.4.3. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

2.4.4. Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7)

2.4.5. Urine Cotinine Test: Cotinine Qual, Cotinine Quant Mid

- Qualitative Test (Cotinine Qual): Positive/negative (results are available within 30 s)

- Quantitative Test (Cotinine Quant Mid): Measures the amount of cotinine in the body to assess how much a person smokes (results are available within 4 min)

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. Ethical Considerations and Informed Consent

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Demographic Characteristics

4. Discussions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Global Tobacco Report 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- WHO. WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use 2000–2025, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Conventional Cigarettes (Rolled Tobacco): Trends in Domestic and International Smoking Rates. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/contents.es?mid=a20205010601 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Weinstein, S.; Mermelstein, R. Influences of Mood Variability, Negative Moods, and Depression on Adolescent Cigarette Smoking. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013, 27, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purwana, R. Dynamics of Well Being on the Young Women Who Smoke as a Coping Stress. J. Kesehat. LLDikti Wil. 1 2022, 2, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. Impact of Smoking on Adolescents Development. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 40, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, J.; Lim, J.S. Poly-Use of Tobacco Products among Korean Adolescents and Its Relationship with Depressive Mood, Loneliness and Anxiety. J. Korean Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2023, 14, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Park, J.Y.; Kwon, E.J.; Choi, S.H.; Cho, H.I. Efficacy of Smoking Cessation and Prevention Programs by Intervention Methods: A Systematic Review of Published Studies in Korean Journals during Recent 3 Years. Korean J. Health Educ. Promot. 2013, 30, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Song, H.Y. Transtheoretical Model to Predict the Stages of Changes in Smoking Cessation Behavior among Adolescents. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1399478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defoe, I.N.; Semon Dubas, J.; Somerville, L.H.; Lugtig, P.; van Aken, M.A. The unique roles of intrapersonal and social factors in adolescent smoking development. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 2044–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; Blackwell, S.E.; Burnett Heyes, S.; Renner, F.; Raes, F. Mental Imagery in Depression: Phenomenology, Potential Mechanisms, and Treatment Implications. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 12, 249–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, A.K.; Moore, R. Positive Thinking Revisited: Positive Cognitions, Well-Being and Mental Health. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2000, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Stress and Coping Mechanisms in South Korean High School Students: Academic Pressure, Social Expectations, and Mental Health Support. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dino, G.; Horn, K.; Abdulkadri, A.; Kalsekar, I.; Branstetter, S. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of the Not On Tobacco Program for Adolescent Smoking Cessation. Prev. Sci. 2008, 9, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azagba, S.; Asbridge, M. School Connectedness and Susceptibility to Smoking Among Adolescents in Canada. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwuzo, C.N.; Olukorode, J.; Sange, W.; Orimoloye, D.A.; Udojike, C.; Omoragbon, L.; Hassan, A.E.; Falade, D.M.; Omiko, R.; Odunaike, O.S.; et al. A Review of Smoking Cessation Interventions: Efficacy, Strategies for Implementation, and Future Directions. Cureus 2024, 16, e52102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, L.; Chao, Y.; Wang, J.; Qin, T.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Hou, L.; Lu, L. Effects of Interventions on Smoking Cessation: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Addict. Biol. 2024, 29, e13376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Sun, P. Youth Tobacco Use Cessation: 2008 Update. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2009, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Fredrickson, B.; Kring, A.M.; Johnson, D.P.; Meyer, P.S.; Penn, D.L. Upward Spirals of Positive Emotions Counter Downward Spirals of Negativity: Insights from the Broaden-and-Build Theory and Affective Neuroscience on the Treatment of Emotion Dysfunctions and Deficits in Psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahler, C.W.; Spillane, N.S.; Day, A.M.; Cioe, P.A.; Parks, A.; Leventhal, A.M.; Brown, R.A. Positive Psychotherapy for Smoking Cessation: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, W.; Oh, Y.S. Examining the Mediating Effect of Believability on the Relationship between Social Influences and Smoking Behavior for Smoking Cessation among Korean Youths. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, G.H.; Yang, M.R.; Park, I.; Oh, B. Multidisciplinary Approach to Smoking Cessation in Late Adolescence: A Pilot Study. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2020, 7, 2333794X20944656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Lee, H.K. The Effects of END Smoking Cessation Motivational Program on Carbon Monoxide, Smoking Abstinence Self-efficiency, Smoking Days and Daily Smoking Amount of Smoking High School Students. J. Korean Appl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 38, 669–679. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.; Bak, S.; Hwang, J.I.C.; Gim, H.; Choe, G.; An, S. Development of Road-map of Smoking Prevention and Cessation for Children and Adolescent; Dankook University: Cheonan, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- van Steenbergen, H.; de Bruijn, E.R.; van Duijvenvoorde, A.C.; van Harmelen, A.L. How Positive Affect Buffers Stress Responses. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 39, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.D.; Siegle, G.J.; Zotev, V.; Phillips, R.; Misaki, M.; Yuan, H.; Drevets, W.C.; Bodurka, J. Randomized Clinical Trial of Real-Time fMRI Amygdala Neurofeedback for Major Depressive Disorder: Effects on Symptoms and Autobiographical Memory Recall. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerström, K.O. Measuring Degree of Physical Dependence to Tobacco Smoking with Reference to Individualization of Treatment. Addict. Behav. 1978, 3, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Frecker, R.C.; Fagerstrom, K.O. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A Revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991, 86, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.K.; Lee, H.J.; Jung, D.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, J.H. The Reliability and Validity of Korean Version of Questionnaire for Nicotine Dependence. J. Korean Acad. Fam. Med. 2002, 23, 999–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, J.F.; Le Houezec, J.; Perneger, T.V. A Self-administered Questionnaire to Measure Dependence on Cigarettes: The Cigarette Dependence Scale. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W. Validation and Utility of a Self-report Version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Choi, H.R.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, K.; Hong, J.P. Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). J. Korean Soc. Anxiety 2010, 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raihan, N.; Cogburn, M. Stages of Change Theory. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Compare, A.; Zarbo, C.; Shonin, E.; Van Gordon, W.; Marconi, C. Emotional Regulation and Depression: A Potential Mediator between Heart and Mind. Cardiovasc. Psychiatry Neurol. 2014, 2014, 324374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askelund, A.D.; Schweizer, S.; Goodyer, I.M.; van Harmelen, A. Positive Memory Specificity Reduces Adolescent Vulnerability to Depression. bioRxiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassel, J.D.; Stroud, L.R.; Paronis, C.A. Smoking, Stress, and Negative Affect: Correlation, Causation, and Context across Stages of Smoking. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 270–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, A.A.; Messman, B.; Gould, P.; Slavish, D.C.; Weiss, N.H. Impacts of repeated retrieval of positive and neutral memories on posttrauma health: An investigative pilot study. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2023, 81, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, R.G.; Szeto, E.H.; Suh, S.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Waters, A.J. Associations between Affect, Craving, and Smoking in Korean Smokers: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020, 12, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, L.F.; Carroll, A.J.; Lancaster, T. Group Behaviour Therapy Programmes for Smoking Cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD001007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asnaani, A.; Vonk, I.J.J.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.Y.; Lim, M.K.; Park, E.; Kim, Y.; Lee, D.; Oh, K. Optimum Urine Cotinine and NNAL Levels to Distinguish Smokers from Non-Smokers by the Changes in Tobacco Control Policy in Korea from 2008 to 2018. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benowitz, N.L.; Bernert, J.T.; Foulds, J.; Hecht, S.S.; Jacob, P.; Jarvis, M.J.; Joseph, A.; Oncken, C.; Piper, M.E. Biochemical Verification of Tobacco Use and Abstinence: 2019 Update. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 22, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, P.S.; Delucchi, K.L.; Hall, S.M. Mechanisms of Change in Extended Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Tobacco Dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 109, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierisch, J.M.; Bastian, L.A.; Calhoun, P.S.; McDuffie, J.R.; Williams, J.W. Smoking Cessation Interventions for Patients with Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Steps (Therapeutic Factor) | Topics | Program Highlights | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Awareness (cognition) | Getting to know me |

|

|

| 2 | Recognition (understanding) |

|

| |

| 3 | Expression (coping strategy) | Sharing my emotions |

|

|

| 4 | Discovery (coping strategy) | Happiness energy charging station |

|

|

| 5 | Awakening (motivation) | Smoking: True or false |

|

|

| 6 | Confidence (coping methods) | Practicing how to say no |

|

|

| 7 | Management (stress management) | Stress, go away! |

|

|

| 8 | Support (Maintenance) | Let’s GO together |

|

|

| Variables | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | M ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 37 | 92.5 | 1.075 ± 0.27 |

| Female | 3 | 7.5 | ||

| Age | 17 | 18 | 45.0 | 17.725 ± 0.75 |

| 18 | 15 | 37.5 | ||

| 19 | 7 | 17.5 | ||

| Family economic status | High | 7 | 17.5 | 2.425 ± 0.81 |

| Middle | 32 | 80.0 | ||

| Low | 1 | 2.5 | ||

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 1–5 | 6 | 15.0 | 14.225 ± 7.73 |

| 6–10 | 8 | 20.0 | ||

| 11–20 | 22 | 55 | ||

| 21 or more | 4 | 10.0 | ||

| Drinking experience | Yes | 31 | 77.5 | 1.23 ± 0.42 |

| No | 9 | 22.5 | ||

| Variable | N | Mean | Paired Sample t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | t | p | Cohen’s d | ||

| Nicotine dependence (FTND) | 40 | 3.00 | 2.40 | 2.204 | 0.033 * | 0.25 |

| Cigarette dependence (CDS-12) | 40 | 32.05 | 28.43 | 2.202 | 0.034 * | 0.31 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 40 | 2.25 | 0.40 | 2.618 | 0.013 ** | 0.37 |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 40 | 2.13 | 0.83 | 2.092 | 0.043 * | 0.40 |

| Smoking status (Cotinine Qual) | 40 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 2.623 | 0.012 * | 0.42 |

| Smoking quantity (Cotinine Quant MID) | 40 | 15.50 | 12.93 | 3.318 | 0.002 ** | 0.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yi, Y.-S.; Kim, H.-S.; Bae, E.; Lee, Y.; Lee, C.M.; Shim, S.H.; Kim, M.; Lim, M.H. Intervention Effects of a School-Based Smoking Cessation Program on Nicotine Dependence and Mental Health Among Korean Adolescent Smokers: The Experience New Days (END) Program. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030081

Yi Y-S, Kim H-S, Bae E, Lee Y, Lee CM, Shim SH, Kim M, Lim MH. Intervention Effects of a School-Based Smoking Cessation Program on Nicotine Dependence and Mental Health Among Korean Adolescent Smokers: The Experience New Days (END) Program. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030081

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, You-Shin, Hye-Seung Kim, Eunju Bae, Youngil Lee, Chang Min Lee, Se Hoon Shim, Minsun Kim, and Myung Ho Lim. 2025. "Intervention Effects of a School-Based Smoking Cessation Program on Nicotine Dependence and Mental Health Among Korean Adolescent Smokers: The Experience New Days (END) Program" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030081

APA StyleYi, Y.-S., Kim, H.-S., Bae, E., Lee, Y., Lee, C. M., Shim, S. H., Kim, M., & Lim, M. H. (2025). Intervention Effects of a School-Based Smoking Cessation Program on Nicotine Dependence and Mental Health Among Korean Adolescent Smokers: The Experience New Days (END) Program. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030081