Abstract

Objective: Cyberbullying among children and adolescents is a serious and increasingly prevalent issue worldwide. Victims often experience various emotional issues such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts, as well as disruptive and impulsive behavioral problems. Therefore, effective therapeutic interventions and social support are essential. This study investigated the effects of group sandplay therapy (GST) on children who have been victims of cyberbullying. Method: This study was designed as a non-randomized controlled trial with an intervention group and a control group. The participants included 127 children aged 11 to 12 years old who had experienced cyberbullying, with 64 participants in the GST intervention group and 63 participants in a matched control group based on gender and age. The intervention group participated in 10 GST sessions, each lasting 40 min, held once a week in groups of three or four. The control group received no treatment. The Korean Youth Self Report (K-YSR) was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention. Results: The results indicated that the GST intervention group experienced significant reductions in anxiety/depression (F = 7.09, p = 0.009, d = 0.49), somatic symptoms (F = 10.02, p = 0.002, d = 0.58), and aggressive behavior (F = 3.94, p = 0.049, d = 0.36) on the K-YSR scale compared to the control group. Conclusions: Thus, GST was found to be effective in alleviating negative emotions and aggressive behavior in children affected by cyberbullying.

1. Introduction

Cyberbullying among children and adolescents has rapidly increased globally and is now one of the most prominent forms of cybercrime [1,2]. Kowalski et al. [2] defined cyberbullying as “the use of electronic communication devices as a medium to harass someone.” This form of bullying can manifest in various ways, including text messaging, emails, social media, chat rooms, and blogs [3]. A meta-analysis by Li et al. [4] highlighted that the rapid development of information and communication technology, coupled with the widespread use of mobile devices by children and adolescents, has led to the emergence of cyberbullying as a new form of harassment. In particular, violent incidents among children and adolescents are becoming increasingly prevalent in virtual spaces rather than being confined to the real world [5].

A survey conducted across 25 countries involving 7644 children and adolescents aged 8 to 17 years old found that, on average, 37% had experienced cyberbullying [6]. In Australia, the UK, Canada, and the United States, reports indicate that between 10% and 42% of respondents have experienced cyberbullying [7]. According to the 2023 Cyberbullying Survey in South Korea, 36.8% of 9218 children and adolescents aged 10 to 18 years old experienced incidents of cyberbullying [8].

Children and adolescents often hesitate to report cyberbullying victimization to teachers or parents or to seek help due to feelings of conflict and a sense of being misunderstood because of parental supervision and control over their online activities [5]. This passivity can lead to serious consequences, such as refusing to attend school, giving up hobbies, and withdrawing from social interactions [9]. Hu et al. [10] found a significant positive association between cyberbullying victimization and depression among children and adolescents, based on findings from 57 studies across 17 countries. A study involving 845 Spanish adolescents aged 13 to 17 years old by Gámez-Guadix et al. [11] found that experiencing cyberbullying can lead to depression, which in turn increases the likelihood of re-exposure to cyberbullying. Children and adolescents who face cyberbullying are known to experience internalizing problems, such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, as well as externalizing problems, including aggressive and impulsive behaviors like violence and substance abuse [12,13]. Studies indicate that victims of cyberbullying are at a higher risk for school-related issues such as truancy, tardiness, and school rule violations, as well as deviant behaviors such as drug and alcohol abuse [14,15]. Furthermore, a study involving 638 Bulgarian adolescents aged 12 to 17 years old found that victims of cyberbullying experienced sleep and eating disorders. These issues persisted over a six-month period, demonstrating the negative impact that cyberbullying can have on physical health, including the development of somatic symptoms [9].

Traumatic experiences such as cyberbullying put children and adolescents at high risk for both physical and psychological problems and can affect neurobiological brain development [16]. Childhood trauma can lead to cognitive, emotional, and social issues, including ADHD, depression, anxiety, and personality disorders, and these problems can continue into adulthood [17]. Additionally, victims of cyberbullying may also become bystanders or even perpetrators of violence [18]. Therefore, early intervention is crucial for children and adolescents exposed to cyberbullying, as it can help break the cycle of repeated victimization and prevent long-term psychological sequelae and side effects.

Sandplay therapy is a psychotherapy method that became widespread with the founding of the International Society for Sandplay Therapy (ISST) in 1985. It has been widely utilized not only in Western countries but also in Asia and Latin America, where it has experienced significant growth over the past 15 years [19]. This therapy has been applied to a diverse range of subjects, including infants, children, and adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems; children exposed to abuse and violence; and children and adults with post-traumatic stress disorder [19,20,21]. In particular, sandplay therapy has proven effective in reducing negative emotions and improving behavioral problems among both children and adults who have experienced traumatic events, including children who have been sexually abused [22], children who survived an earthquake in Nepal [23], refugee preschoolers who experienced a tsunami [24], children who have been victims of abuse [25], war veterans [26], migrant women exposed to domestic violence [27], and children who experienced the World Trade Center attacks [28]. However, research on the effectiveness of GST for victims of cyberbullying remains limited. Thus, this study aims to examine the effectiveness of GST in alleviating internalizing and externalizing problems for children who have been victims of cyberbullying.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was designed as a non-randomized controlled trial consisting of an intervention group and a control group to evaluate the effectiveness of GST for children who are victims of cyberbullying. The intervention group received GST following a pre-test, while the control group received no treatment. Both groups underwent pre- and post-tests. The research was conducted over 18 months, from September 2022 to December 2023, in a sandplay therapy room at an elementary school in Asan, South Korea. Before starting the program, two sandplay therapy specialists and two child counseling experts convened multiple meetings to discuss the rules, suggestions, methods of implementation, and necessary precautions for it. The program was conducted by a professional therapist with over 10 years of experience in sandplay therapy, with clinical supervision provided by a pediatric and adolescent psychiatrist.

2.2. Participants

A cyberbullying victimization survey was conducted among 573 fifth- and sixth-grade students at an elementary school in Asan City. From this group, 195 children were selected based on their responses to eight questions addressing their experiences with cyberbullying. These questions measured the frequency of victimization, with the following options: (1) at least once or twice every six months in the past year, (2) once or twice a month, (3) once or twice a week, and (4) once or twice almost every day. Based on the work of Kowalski et al. [29] the victims were identified based on their frequency of victimization, as cyberbullying typically does not occur as a single event; instead, it often involves the ongoing sharing and disseminating of harmful photos, comments, and content. The inclusion criteria required that children had experienced cyberbullying within the past year, as determined through a questionnaire. Participants were limited to those who voluntarily agreed to be involved in the study and who had obtained parental consent. Of the 195 children, 68 were excluded due to refusal to participate in the program (n = 64), hospital care (n = 3), and other reasons (n = 1). Consequently, 127 children received the intervention and were evaluated in this study. They were diagnosed and assessed by a pediatric psychiatrist according to the DSM-5 criteria, ensuring that none had developmental disorders such as childhood psychosis, autism, or intellectual disabilities, nor were they taking any medications. Among them, 64 students were randomized to the GST intervention group, while 63 were assigned to the control group. There was no psychiatric disorder in either the intervention or control group.

2.3. Intervention

Before the study began, the purpose and procedures were clearly explained, and written informed consent was obtained from all participating children. Those in the GST intervention group received ten 40 min sandplay therapy sessions held once a week during after-school hours or creative hands-on activity periods. Each child was provided with a sand tray measuring 72 cm wide, 57 cm high, and 7 cm deep, in accordance with international standards. Each therapy group consisted of one therapist and 3 to 4 children. The program included thousands of miniatures representing people, buildings, plants, animals, vehicles, and household items, which were shared among the children. The program was adapted from Boik and Goodwin’s [20] Sandplay Therapy: A Step-by-Step Manual for Psychotherapists of Diverse Orientation and Kalff’s [30] Introduction to Sandplay Therapy, based on the school sandplay group therapy program developed by Kwak et al. [31] (Table 1). During the sessions, children created sand trays, showcased their finished works, and shared their experiences with group members. The group members interacted with and supported one another, and the therapist encouraged free expression of their emotions.

Table 1.

Contents of the GST intervention program.

2.4. Measures

Korean Youth Self Report: K-YSR

The Youth Self Report (YSR), developed by Achenbach [32], is a self-report measure used to assess emotional/behavioral issues in adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18. In this study, the Korean Youth Self Report (K-YSR), adapted and standardized by Oh et al. [33], was utilized. The K-YSR includes the Problem Behavior Syndrome Scale and the Social Competence Syndrome Scale, with each item rated on a 3-point Likert scale. For this research, only the Problem Behavior Syndrome Scale was employed. This scale comprises nine subscales, including internalizing (anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, somatic symptoms), externalizing (aggressive behavior, rule-breaking), social immaturity, cognitive issues, attention problems, and other problems. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.949.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0 was used for statistical analysis. Chi-squared tests were conducted for gender comparisons, while t-tests were performed for age comparisons to assess the homogeneity of demographic characteristics. Repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) was employed to evaluate pre–post changes between the intervention and control groups. In addition, Cohen’s d value was calculated to determine the effect size according to the pre–post mean difference between the two groups.

2.6. Ethical Considerations and Informed Consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Board and Research Ethics Committee of Dankook University (Identification Code: DKU 2020-03-004). The purpose and procedures of the study were thoroughly explained to all participating children. Written informed consent was obtained from both the participating children and their parents, who were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time during the study.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

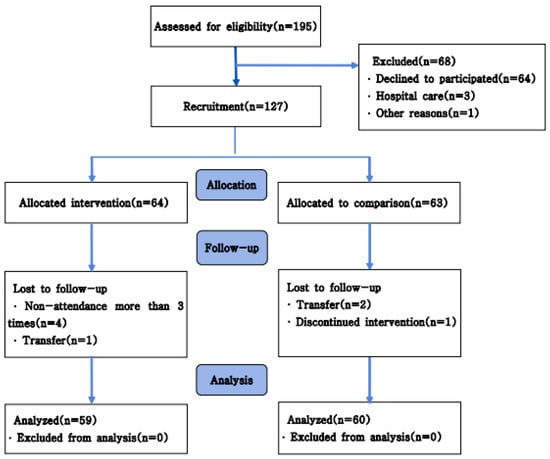

Of the 127 children who agreed to participate, 119 completed the post-test (GST = 59, COMP = 60). Five children from the intervention group were excluded from the analysis because they missed three or more sessions (n = 4) or transferred to another school (n = 1). In the control group, three participants were excluded from the analysis due to transferring to another school (n = 2) or discontinued due to other interventions outside of school (n = 1) (Figure 1). All participating children were 11–12 years old. The mean age of the intervention group was 11.39 years (SD = 0.48), while the mean age of the control group was 11.32 years (SD = 0.47). No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of age (t = 0.70, p = 0.404) or gender (χ2 = 0.014, p = 0.906) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the intervention group (n = 59) and control group (n = 60).

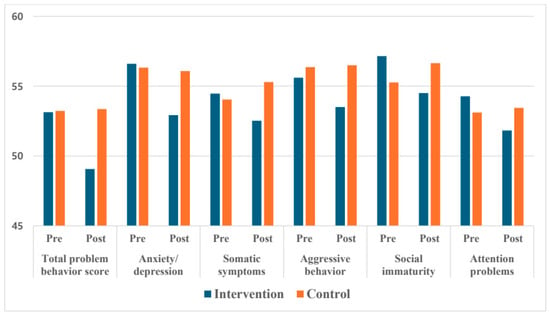

3.2. Changes in K-YSR After GST Intervention

An independent samples t-test was conducted to assess the homogeneity between the intervention and control groups. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups regarding the total problem behavior score and syndrome subscales of the K-YSR. While the K-YSR total problem behavior score did not show significant differences between groups, there were significant changes over time (F = 4.171, p = 0.043) and interaction between the groups (F = 4.755, p = 0.031). Anxiety/depression was not significant in the main effect of the group but was significant in the main effect of time (F = 9.313, p = 0.003) and the interaction effect (F = 7.039, p = 0.009). Somatic symptoms (F = 10.023, p = 0.002), aggressive behavior (F = 3.940, p = 0.049), social immaturity (F = 10.632, p = 0.001), and attention problems (F = 4.079, p = 0.046) were not significant in the main effects of group and time but were significant in the interaction effect. Other problems were significant for the group (F = 5.004, p = 0.027) but not for time and interaction. Withdrawal/depression, rule-breaking, and cognitive issues were not significant for group, time, or interaction. Overall, after the GST intervention, the intervention group exhibited significant reductions in the K-YSR total problem behavior score, anxiety/depression, somatic symptoms, aggressive behavior, social immaturity, and attention problems compared to the control group (Table 3). The graphs illustrating the differences of pre–post changes between the two groups over time for these measures are shown in Figure 2. In addition, the effect size according to the pre–post mean difference between the two groups showed a medium effect size in the total problem behavior score, anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression, somatic symptoms, rule-breaking, aggressive behavior, social immaturity, and attention problems (ranging from 0.34 to 0.60 across these measures). While there was a small effect size for cognitive issues (d = 0.20) and other problems (d = 0.04).

Table 3.

Pre- and post-test differences between intervention and control groups using RM-ANOVA (N = 119).

Figure 2.

Graphs of means differences in total problem behavior score, anxiety/depression, somatic symptoms, aggressive behavior, social immaturity, attention problems.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to test the effectiveness of GST on internalizing and externalizing problems in children who had experienced cyberbullying. The findings indicated positive changes in anxiety/depression, somatic symptoms, aggressive behavior, social immaturity, and attention problems in the intervention group after GST intervention.

First, GST reduced the negative emotional symptoms of anxiety and depression in the intervention group. This result aligns with previous research on school violence [31,34]. For instance, a study involving 105 immigrant and refugee preschoolers in a multiethnic South Asian neighborhood found that sandplay therapy significantly alleviated anxiety and depression in 52 participants from the intervention group [24]. In addition, a study examining the effects of GST on the psychological health and resilience of 12 adolescent survivors of a 2015 earthquake in Nepal showed a decrease in anxiety/depression and withdrawal/depression, indicating that the program effectively improved their psychological health [23].

Second, the somatic symptoms of children in the GST intervention group decreased significantly, supporting previous studies on the effectiveness of GST for these issues. Roubenzadeh et al. [35] conducted GST with adolescents who were grieving the loss of a family member and reported that 10 adolescents in the intervention group had significantly reduced somatic symptoms and were more effective in coping with their feelings of grief compared to the control group. Lee [36] found improvements in somatic symptoms among children from divorced families after participating in GST. Cao et al. [37] reported that adolescents with PTSD exhibited improvements in both somatic and negative emotional symptoms following sandplay therapy, with effects sustained at a six-month follow-up.

Third, children in the intervention group exhibited reductions in aggressive behavior after GST intervention, which was consistent with previous studies. Han [38] investigated the effects of sandplay therapy on 20 children (10 from the intervention group, 10 from the control group) aged 4 to 5 years old with externalizing problems and reported a decrease in aggressive behavior and negative peer interaction problems. In a study of pre-adolescents with conduct disorders (n = 56), the intervention group (n = 28) demonstrated significant differences in teacher-rated externalizing problem behaviors after GST intervention compared to the control group. These findings suggest that GST may have a positive therapeutic effect on pre-adolescents with conduct disorders and help prevent their symptoms from worsening [39]. Furthermore, Sim and Jang [40] found that sandplay therapy led to decreased aggressive behavior and positive changes in EEG indices related to aggression among nine female juvenile delinquents.

Fourth, significant improvements in social immaturity and internalizing/externalizing problems were found in the intervention group after GST, which is consistent with previous studies. Zheng and Hu [41] implemented GST for adolescents from divorced families. After the intervention, the intervention group showed enhanced interpersonal trust levels compared to the control group, suggesting that GST can help improve interpersonal problems. Kazemi et al. [42] also reported that, among 30 children aged 7 to 12 years old diagnosed with separation anxiety disorder, 15 children in the intervention group showed improved social skills and adaptability after receiving sandplay therapy.

Finally, the intervention group demonstrated improvements in attention problems after GST. These results support previous studies that reported the effectiveness of sandplay therapy in addressing attention deficit issues in children with ADHD [43,44]. Wang et al. [45] reported reductions in symptoms of attention deficit, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention in the intervention group (n = 15) after 12 sessions of sandplay therapy, which is consistent with the present study.

Although there are only a few studies on the effectiveness of sandplay therapy for school violence victims, school sandplay group therapy reduced depression and suicidal ideation and increased self-esteem among these victims. GST was also found to be effective in improving self-expression and school adjustment in victims of school violence [46]. Matta and Ramos [25] observed improvements in both internalizing and externalizing problems among a group of 60 children (aged 6 to 10 years old) exposed to violence after participating in sandplay therapy. The findings of this study are interpreted as a result of the children expressing their emotions and experiences without resistance in a safe and sheltered space [30]. The therapist did not interpret or direct the sand tray but instead unconditionally accepted the children without judgment, providing the trust and safety needed for them to express their trauma. It is believed that through non-verbal communication using sand and symbols, the children in this study could safely and freely articulate their trauma, leading to improvements in negative emotions and aggressive behaviors. Trauma is a sensory-based experience stored in implicit memory, which can impair brain function. GST is thought to help transform trauma from implicit to explicit memory, promoting healing by restoring brain function through a creative and emotional approach that uses physical sensations, such as seeing, touching, and feeling the sand [16,21].

5. Conclusions

The study found that GST was effective in improving anxiety/depression, somatic symptoms, aggressive behavior, social immaturity, and attention problems in children affected by cyberbullying. GST could be used as an important treatment for children who are victims of cyberbullying, a growing public health problem worldwide.

On the other hand, there are several limitations to this study that should be noted. First, the evaluation relied solely on self-reported questionnaires. Further research, including EEG or neuroimaging studies, as well as parent and teacher evaluations, is needed to objectively and scientifically validate the effectiveness of GST. Second, since our post-test was conducted immediately after the GST intervention, follow-up studies are needed to confirm the long-term treatment effects of GST. Third, there are limitations in generalizing the effectiveness of the program because it was implemented in a single elementary school within a single region, so future studies should include a broader range of regions and age groups.

Despite these limitations, this study is significant as it is one of the few to examine the clinical effectiveness of GST on child victims of cyberbullying. It uses the K-YSR to assess the effectiveness of GST across subscales, including internalizing/externalizing problem behaviors. The findings suggest that GST is an effective technique for treating trauma related to abuse, violence, disasters, and the aftereffects of violence experienced in cyberspace.

Author Contributions

H.-A.K. performed intervention group treatment, analyzed and interpreted the data, wrote the first manuscript. M.-B.L. was in charge of the treatment of the intervention group. Y.L., C.M.L., D.H.K., Y.L.L. and M.K. performed the statistics for analysis and interpreted the data. M.H.L. integrated the analyzed data, wrote and revised this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethical review committee of Dankook University (Approval Code: DKU 2020-03-004; Approval date: 12 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical approval requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| GST | Group Sandplay Therapy |

References

- Beckman, L.; Hagquist, C.; Hellström, L. Does the Association with Psychosomatic Health Problems Differ between Cyberbullying and Traditional Bullying? Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2012, 17, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the Digital Age: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of Cyberbullying Research among Youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauman, M.A. Cyber Bullying: Bullying in the Digital Age. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, P.; Martin-Moratinos, M.; Bella-Fernández, M.; Blasco-Fontecilla, H. Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying in the Digital Age and Its Associated Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 33, 2895–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umesh, B.; Ali, N.N.; Farzana, R.; Bindal, P.; Aminath, N.N. Student and Teachers Perspective on Cyber-Bullying. J. Forensic Psychol. 2018, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, C.S.; Chang, S.-H.; Ragan, M.A. Cyberbullyingin Asia. Educ. Asia 2013, 18, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, E. Cyberbullying: A Worldwide Trend of Misusing Technology to Harass Others. WIT Trans. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2006, 36, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- NIA Statistical Information System. 2024. Available online: https://www.nia.or.kr/site/nia_kor/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=68302&bcIdx=26483&parentSeq=26483 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Mancheva, R. Psychosomatic and Behavioral Shanges in Victims of gyberbullying. Knowl.—Int. J. 2021, 47, 925–931. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, S. Cyberbullying Victimization and Depression among Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 305, 114198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Orue, I.; Smith, P.K.; Calvete, E. Longitudinal and Reciprocal Relations of Cyberbullying with Depression, Substance Use, and Problematic Internet Use Among Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.W.; Gardella, J.H.; Teurbe-Tolon, A.R. Peer Cybervictimization Among Adolescents and the Associated Internalizing and Externalizing Problems: A Meta-Analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1727–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Lalande, K.; Colman, I. Cyberbullying Victimisation and Internalising and Externalising Problems among Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Relationship and Child’s Sex. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Cyberbullying Among Adolescents: Implications for Empirical Research. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 431–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Diener-West, M.; Leaf, P.J. Examining the Overlap in Internet Harassment and School Bullying: Implications for School Intervention. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S42–S50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freedle, L.R. Healing Trauma through Sandplay Therapy: A Neuropsychological Perspective. In The Routledge International Handbook of Sandplay Therapy; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, H. The Impact and Long-Term Effects of Childhood Trauma. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2018, 28, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandebosch, H.; Van Cleemput, K. Cyberbullying among Youngsters: Profiles of Bullies and Victims. N. Media Soc. 2009, 11, 1349–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, C. Sandplay Therapy: An Overview of Theory, Applications and Evidence Base. Arts Psychother. 2019, 64, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boik, B.; Goodwin, E.A. Sandplay Therapy: A Step by Step Manual for Psychotherapists of Diverse Orientation; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, M.; Wilson, H. Sandplay Therapy: A Safe, Creative Space for Trauma Recovery. Aust. Couns. Res. J. 2019, 13, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tornero, M.D.L.A.; Capella, C. Change during Psychotherapy through Sand Play Tray in Children That Have Been Sexually Abused. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jang, M. The Effect of Group Sandplay Therapy on Psychological Health and Resilience of Adolescent Survivors of Nepal Earthquake. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2020, 11, 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Benoit, M.; Lacroix, L.; Gauthier, M.-F. Evaluation of a Sandplay Program for Preschoolers in a Multiethnic Neighborhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta, R.M.D.; Ramos, D.G. The Effectiveness of Sandplay Therapy in Children Who Are Victims of Maltreatment with Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems. Estud. Psicol. 2021, 38, e200036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troshikhina, E. Sandplay Therapy for the Healing of Trauma. In Is This a Culture of Trauma? An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. An Effect of Sandplay Therapy on PTSD Symptoms of Migrant Women Victims of Domestic Violence in South Korea. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 9594–9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.J.; Aslan, S.M.; Mendoza, V.E.; Tsukamoto, M. The Use of Sandplay Therapy in Urban Elementary Schools as a Crisis Response to the World Trade Center Attacks. Psychol. Res. 2015, 5, 413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P.; Agatston, P.W. Cyber Bullying: The New Moral Frontier; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2008; Volume 10, p. 9780470694176. [Google Scholar]

- Kalff, D.M. Introduction to Sandplay Therapy. J. Sandplay Ther. 1991, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, H.J.; Ahn, U.K.; Lim, M.H. The Clinical Effects of School Sandplay Group Therapy on General Children with a Focus on Korea Child & Youth Personality Test. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile; University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K.J.; Ha, E.H.; Lee, H.L.; Hong, K.E. Korean Youth Self Report; Seoul National University Press: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, U.K.; Kwak, H.J.; Lim, M.H. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory of School Sandplay Group Therapy with Maladjustment Behavior in Korean Adolescent. Medicine 2020, 99, e23272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roubenzadeh, S.; Abedin, A.; Heidari, M. Effectiveness of Sand Tray Short Term Group Therapy with Grieving Youth. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 69, 2131–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S. Effects of Group Sand-Play Therapy on Children’s Improvement in Peer Relational Skills and Reduction in Behavioral Problems. Unpublished. Master’s Thesis, Namseoul University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Jin, L.; Cui, C.; Cui, M. A Study on the Effects of Sandplay Therapy on Second Grade Middle School Students with PTSD. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2019, 10, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Lee, Y.; Suh, J.H. Effects of a Sandplay Therapy Program at a Childcare Center on Children with Externalizing Behavioral Problems. Arts Psychother. 2017, 52, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flahive, M.W.; Ray, D. Effect of Group Sandtray Therapy with Preadolescents. J. Spec. Group Work 2007, 32, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, E.; Jang, M. Effects of Sandplay Therapy on Aggression and Brain Waves of Female Juvenile Delinquents. J. Symb. Sandplay Ther. 2013, 4, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Hu, Y. The Effect of Group Sandplay Therapy on Interpersonal Trust of Adolescents. Adv. Psychol. 2019, 9, 1899–1906. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, E.; Ashrafi, M.; Maryam Sadat Hosseinzadeh, M.S.H.; Andalibipour, Z.; Rajab Ali, S.; Mehran Mohebian Far, M.M.F. The Effectiveness of Sand Play Therapy on Social Skills and Adaptation of Children with Separation Anxiety. Iran. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 3, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadampour, E.; Shahbazirad, A.; Haghighi Kermanshahi, M.; Mohammadi, F.; Naseri, N. The Effects of Sand Play Therapy in Reduction of Impulsivity and Attention Deficit in Boys with ADHD. Q. J. Child Ment. Health 2018, 5, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Lu, Y.; Wu, J. Sandplay Therapy as a Complementary Treatment for Children with ADHD: A Scoping Review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 44, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.-M.; Hang, G.; Zhang, X.-L.; He, X.-L.; Wang, D.-D. Effects of Sandplay Therapy in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2010, 24, 691–695. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.G.; Kim, H.W.; Park, B.J. The Effect of Group Sandplay Therapy on Self-Expression and School Adjustment of School Violence Victims. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2013, 20, 175–202. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).