Are Disturbances in Mentalization Ability Similar Between Schizophrenic Patients and Borderline Personality Disorder Patients?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test

2.3. Faux Pas Recognition Test (FP-T)

2.4. The Empathy Quotient Scale (EQ Scale)

2.5. Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characterization

3.2. Reading the Mind in the Eyes Is Impaired in Individuals with Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, and BPD

3.3. Recognition of the Faux Pas Motif Is Impaired in Individuals with Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Disorder, and BPD

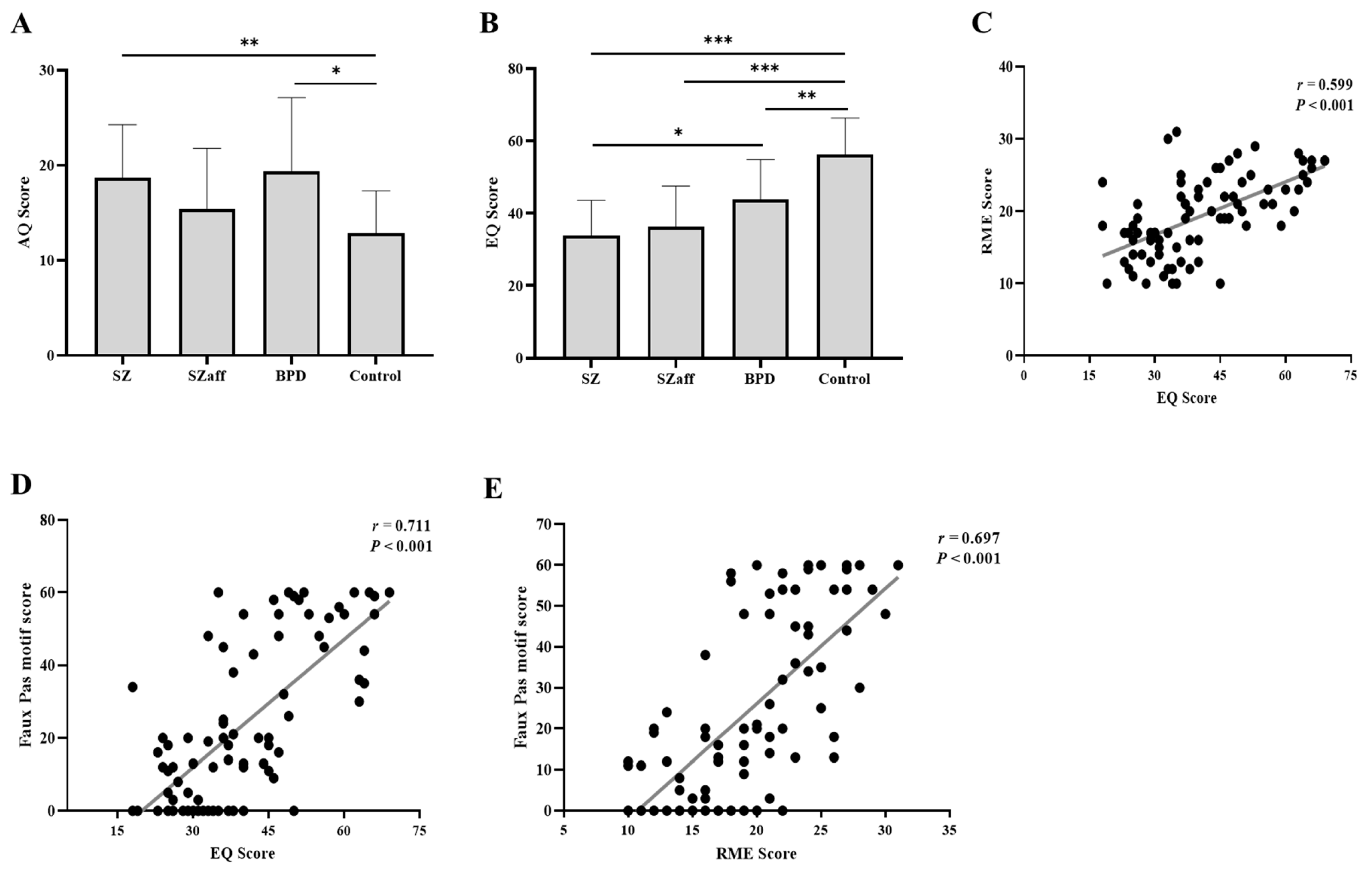

3.4. Assessment of Autistic Symptoms and Empathy

3.5. Correlation Analysis Between the Eyes Test, Faux Pas, EQ, and AQ

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, M.F.; Horan, W.P.; Lee, J. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaretto, E.; Bedani, F.; Brancati, G.; De Berardis, D.; Giovannini, S.; Scarcella, L.; Martiadis, V.; Martini, A.; Pampaloni, I.; Perugi, G.; et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 362, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodell-Feder, D.; Tully, L.M.; Lincoln, S.H.; Hooker, C.I. The neural basis of theory of mind and its relationship to social functioning and social anhedonia in individuals with schizophrenia. NeuroImage Clin. 2014, 4, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, R.R.; Guimond, S.; Bannai, D.; Zeng, V.; Padani, S.; Eack, S.M.; Keshavan, M.S. Theory of Mind Impairments in Early Course Schizophrenia: An fMRI Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucurovic, K.; Caillies, S.; Kaladjian, A. Neural correlates of theory of mind and empathy in schizophrenia: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 120, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprong, M.; Schothorst, P.; Vos, E.; Hox, J.; Van Engeland, H. Theory of mind in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis Review Article Author’s Proof Theory of mind in schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 191, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, E.; Yucel, M.; Pantelis, C. Theory of mind impairment in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrão, J.; Akiba, H.T.; Lederman, V.R.G.; Dias, Á.M. Teste de Faux Pas em pacientes com esquizofrenia. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2016, 65, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kronbichler, L.; Tschernegg, M.; Martin, A.I.; Schurz, M.; Kronbichler, M. Abnormal Brain Activation During Theory of Mind Tasks in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2017, 43, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadmor, H.; Levin, M.; Dadon, T.; Meiman, M.E.; Ajameeh, A.; Mazzawi, H.; Rigbi, A.; Kremer, I.; Golani, I.; Shamir, A. Decoding emotion of the other differs among schizophrenia patients and schizoaffective patients: A pilot study. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2016, 5, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, E.; Yücel, M.; Pantelis, C. Theory of mind impairment: A distinct trait-marker for schizophrenia spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder? Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009, 120, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Németh, N.; Mátrai, P.; Hegyi, P.; Czéh, B.; Czopf, L.; Hussain, A.; Pammer, J.; Szabó, I.; Solymár, M.; Kiss, L.; et al. Theory of mind disturbances in borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normann-Eide, E.; Antonsen, B.T.; Kvarstein, E.H.; Pedersen, G.; Vaskinn, A.; Wilberg, T. Are impairments in theory of mind specific to borderline personality disorder? J. Pers. Disord. 2020, 34, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.; Jo, S.-H.; Jeon, H.-J.; Choo, B.; Seok, J.-H.; Shin, H.; Kim, I.-Y.; Choi, S.-W.; Koo, B.-H. Neurophysiological insights into impaired mentalization in borderline personality disorder an electroencephalography study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1293347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Skinner, R.; Martin, J.; Clubley, E. The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, O.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Hill, J.J.; Golan, Y. The “reading the mind in films” task: Complex emotion recognition in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions. Soc. Neurosci. 2006, 1, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.; Raste, Y.; Plumb, I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Bowen, D.C.; Holt, R.J.; Allison, C.; Auyeung, B.; Lombardo, M.V.; Smith, P.; Lai, M.-C. The “reading the mind in the eyes” test: Complete absence of typical sex difference in ~400 men and women with autism. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.; Lough, S.; Stone, V.; Erzinclioglu, S.; Martin, L.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Hodges, J.R. Theory of mind in patients with frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Theoretical and practical implications. Brain 2002, 125, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S. The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheelwright, S.; Auyeung, B.; Allison, C.; Baron-Cohen, S. Defining the broader, medium and narrow autism phenotype among parents using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ). Mol. Autism 2010, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, G.; Zabihzadeh, A.; Richman, M.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mohammadnejad, F. Decoding and reasoning mental states in major depression and social anxiety disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, L.I.; Heinrichs, R.W.; Mashhadi, F. The continuing story of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: One condition or two? Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2019, 16, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, S.R.; Giuliano, A.J.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Breiger, D.; Sikich, L.; Frazier, J.A.; Findling, R.L.; McClellan, J.; Hamer, R.M.; Vitiello, B.; et al. Neurocognition in early-onset schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, F.; Sanna, L.; Perra, V.; Randaccio, R.P.; Diana, E.; Carpiniello, B.; The Cagliari Recovery Study Group. Long-term outcome of schizoaffective disorder. Are there any differences with respect to schizophrenia? Riv. Psichiatr. 2014, 49, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoso, A.; Carter, C.S.; Gold, J.M.; MacDonald, A.W.; Ragland, J.D.; Silverstein, S.M.; Strauss, M.E.; Barch, D.M. Cognition in schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: Impairments that are more similar than different. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 2535–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupama, V.; Bhola, P.; Thirthalli, J.; Mehta, U.M. Pattern of social cognition deficits in individuals with borderline personality disorder. Asian J. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, M.J.; Unoka, Z. Mental state decoding impairment in major depression and borderline personality disorder: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaskinn, A.; Antonsen, B.T.; Fretland, R.A.; Dziobek, I.; Sundet, K.; Wilberg, T. Theory of mind in women with borderline personality disorder or schizophrenia: Differences in overall ability and error patterns. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, C.; Kelm, L.; Bierbrodt, J.; Braun, V.; Lipp, M.; Yassari, A.H.; Moritz, S. Factors contributing to social cognition impairment in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, C.I.; Verosky, S.C.; Germine, L.T.; Knight, R.T.; D’esposito, M. Mentalizing about emotion and its relationship to empathy. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2008, 3, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, K.; Bluschke, S.; Konradt, B.; Walter, H. Functional relations of empathy and mentalizing: An fMRI study on the neural basis of cognitive empathy. Neuroimage 2010, 54, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, H.J.; Cane, J.E.; Douchkov, M.; Wright, D. Empathy predicts false belief reasoning ability: Evidence from the N400. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014, 10, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Controls (n = 18) | SZ (n = 44) | SZaff (n = 11) | BPD (n = 11) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.3 ± 2.8 | 41.2 ± 1.8 | 41.2 ± 3.4 | 30.8 ± 3.1 | p = 0.028 a |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 7 (39%) | 36 (82%) | 7 (64%) | 2 (18%) | |

| Women | 11 (61%) | 8 (18%) | 4 (36%) | 9 (82%) | |

| Education (years) | 17.1 ± 0.6 | 12.1 ± 0.3 | 12.4 ± 0.4 | 11.2 ± 0.5 | p < 0.001 a |

| Onset (years) | 29.4 ± 1.5 | 28.9 ± 2.8 | 26.7 ± 3.4 | p = 0.73 a | |

| No. of hospitalizations | 11.5 ± 1.7 | 9.4 ± 2.6 | 6.7 ± 2.5 | p = 0.22 b | |

| Years of illness | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 12.5 ± 1.9 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | p = 0.021 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Awad-Igbaria, Y.; Bar, T.; Ikshaibon, E.; Abu-Alhiga, M.; Peleg, T.; Palzur, E.; Golani, I.; Peleg, I.; Shamir, A. Are Disturbances in Mentalization Ability Similar Between Schizophrenic Patients and Borderline Personality Disorder Patients? Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030077

Awad-Igbaria Y, Bar T, Ikshaibon E, Abu-Alhiga M, Peleg T, Palzur E, Golani I, Peleg I, Shamir A. Are Disturbances in Mentalization Ability Similar Between Schizophrenic Patients and Borderline Personality Disorder Patients? Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030077

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwad-Igbaria, Yaseen, Tair Bar, Essam Ikshaibon, Muhammad Abu-Alhiga, Tamar Peleg, Eilam Palzur, Idit Golani, Ido Peleg, and Alon Shamir. 2025. "Are Disturbances in Mentalization Ability Similar Between Schizophrenic Patients and Borderline Personality Disorder Patients?" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030077

APA StyleAwad-Igbaria, Y., Bar, T., Ikshaibon, E., Abu-Alhiga, M., Peleg, T., Palzur, E., Golani, I., Peleg, I., & Shamir, A. (2025). Are Disturbances in Mentalization Ability Similar Between Schizophrenic Patients and Borderline Personality Disorder Patients? Psychiatry International, 6(3), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030077