Effects of Physical Activity or Exercise on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Esteem in Older Adults: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy for Item Identification

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

| Authors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguiñaga et al. [29] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Araque-Martínez et al. [30] | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| Borbón-Castro et al. [31] | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Blumenthal et al. [32] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Escolar and De Guzman [33] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Motl et al. [34] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Sung [35] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

2.4. Summary of Information

3. Results

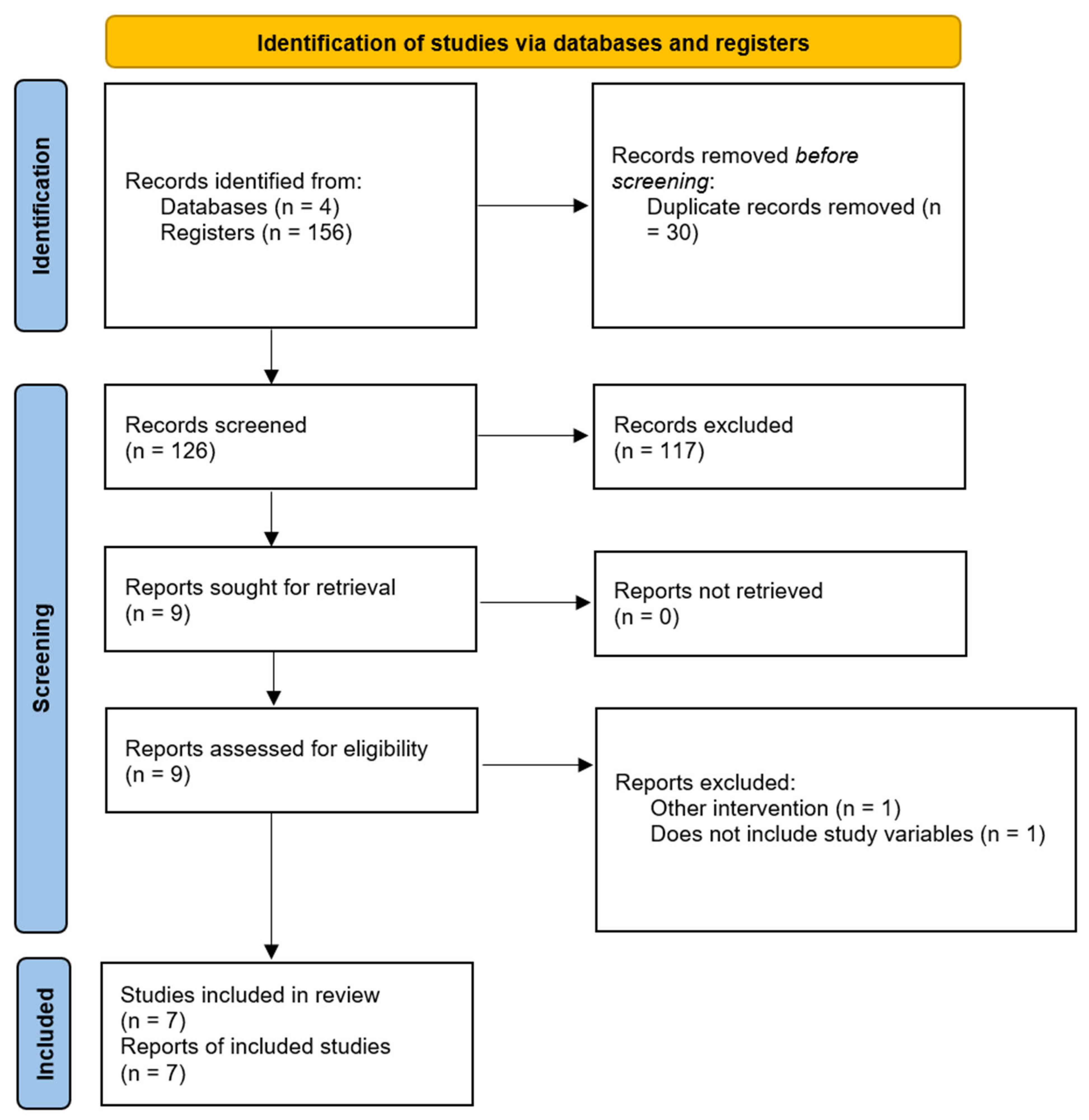

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. PEDro Scale

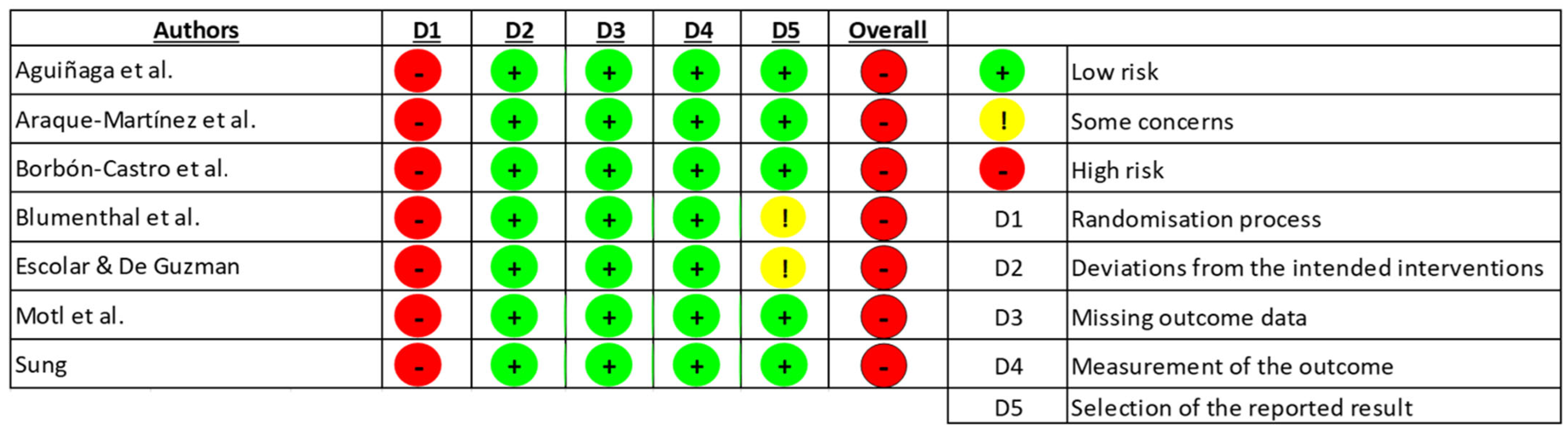

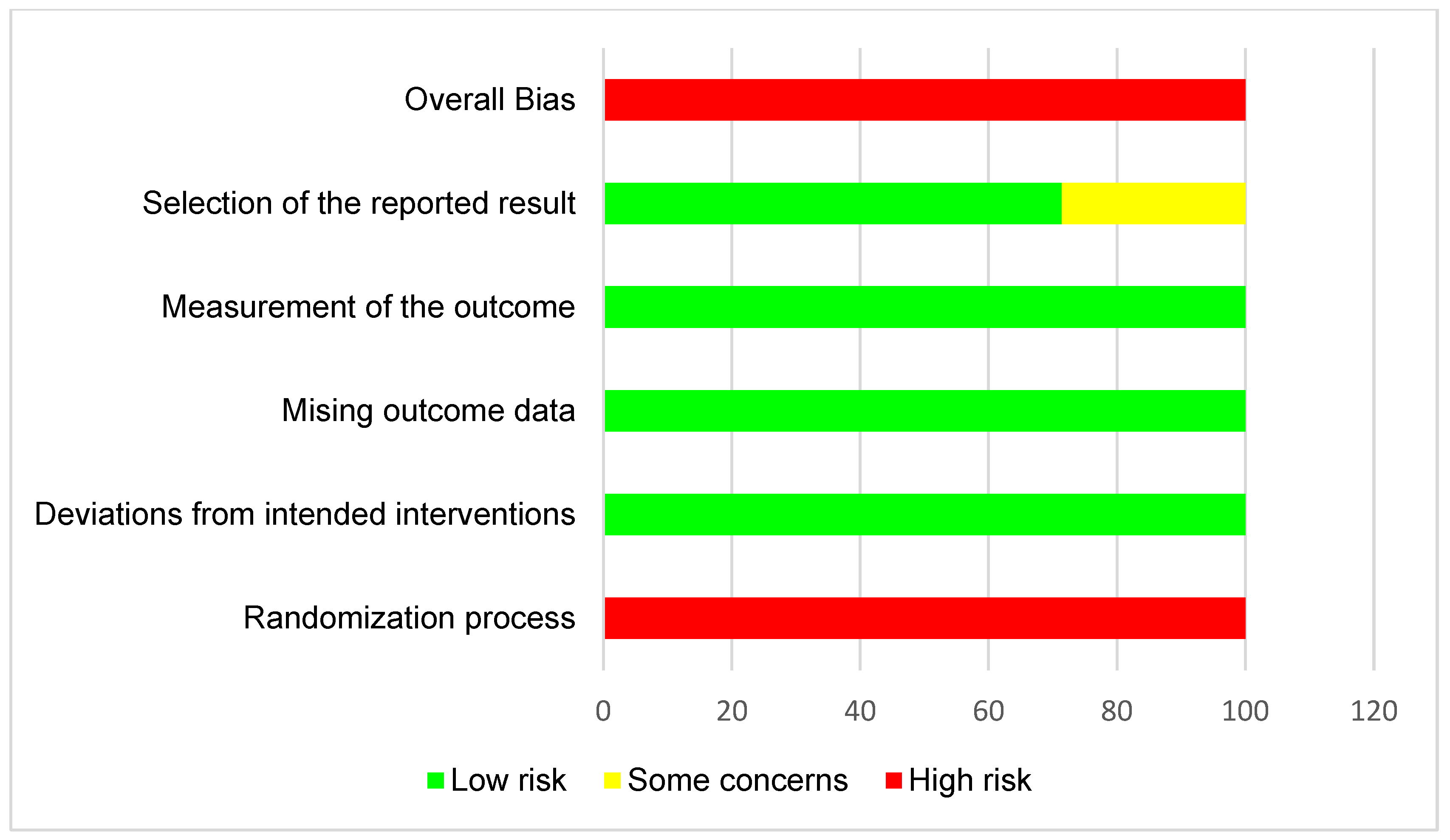

3.3. Risk of Bias

3.4. Characteristics of the Studies

3.5. Description of Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Depressive Symptoms and Self-Esteem

4.2. Other Study Variables

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

4.4. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García Pulgarín, L.V.; García Ortiz, L.H. El adulto mayor maduro: Condiciones actuales de vida. Rev. Médica De Risaralda 2005, 11, 10. Available online: https://revistas.utp.edu.co/index.php/revistamedica/article/view/1189 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Abaunza Forero, C.I.; Mendoza Molina, M.A.; Bustos Benítez, P.; Paredes Álvarez, G.; Enriquez Wilches, K.V.; Padilla Muñoz, A.C. Adultos Mayores Privados de la Libertad en Colombia; Editorial Universidad del Rosario: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Salud Mental de los Adultos Mayores. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Palma-Ayllón, E.; Escarabajal-Arrieta, M.D. Efectos de la soledad en la salud de las personas mayores. Gerokomos 2021, 32, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Depresión. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression#:~:text=Se%20estima%20que%20el%203,personas%20sufren%20depresi%C3%B3n%20(1) (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Felipe, L.R.R.; Barbosa, K.S.S.; Virtuoso Junior, J.S. Sintomatologia depressiva e mortalidade em idosos da América Latina: Uma revisão sistemática com metanálise. Rev. Panam. De Salud Pública 2023, 46, e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud. Guía Práctica en Salud Mental y Prevención de Suicidio para Personas Mayores. Available online: https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019.10.08_Gu%C3%ADa-Pr%C3%A1ctica-Salud-Mental-y-prevenci%C3%B3n-de-suicidio-en-Personas-Mayores_versi%C3%B3n-digital.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Šare, S.; Ljubičić, M.; Gusar, I.; Čanović, S.; Konjevoda, S. Self-Esteem, Anxiety, and Depression in Older People in Nursing Homes. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Pérez, J.I.; Mozaz, M. Self-concept, self-esteem and psychopathological symptoms. Psicothema 2008, 20, 114–123. Available online: https://www.psicothema.com/pdf/3436.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2024). [PubMed]

- Calderón, M.D. Epidemiología de la depresión en el adulto mayor. Rev. Medica Hered. 2018, 29, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Aprahamian, I.; Arai, H.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Bernabei, R.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; et al. International exercise recommendations in older adults (ICFSR): Expert consensus guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 824–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggin, J. What is physical activity? A holistic definition for teachers, researchers and policy makers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzum, H.; Stickel, A.; Corona, M.; Zeller, M.; Melrose, R.J.; Wilkins, S.S. Potential Benefits of Physical Activity in MCI and Dementia. Behav. Neurol. 2020, 2020, 7807856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, B.; Bergland, A.; Rydwik, E. The Importance of Physical Activity Exercise among Older People. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7856823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, D.M.; Ferreira, D.L.; Gonçalves, G.H.; Farche, A.C.S.; de Oliveira, J.C.; Ansai, J.H. Effects of aquatic physical exercise on neuropsychological factors in older people: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 96, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooney, G.M.; Dwan, K.; Greig, C.A.; Lawlor, D.A.; Rimer, J.; Waugh, F.R.; McMurdo, M.; Mead, G.E. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 9, CD004366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvam, S.; Kleppe, C.L.; Nordhus, I.H.; Hovland, A. Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 202, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.; Cipriano, I.; Costa, T.; Saraiva, M.; Martins, A. AGA@4life Consortium. Exercise, ageing and cognitive function—Effects of a personalized physical exercise program in the cognitive function of older adults. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 202, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujral, S.; Aizenstein, H.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Butters, M.A.; Grove, G.; Karp, J.F.; Erickson, K.I. Exercise for Depression: A Feasibility Trial Exploring Neural Mechanisms. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.; Fong, T.; Chan, W.C.; Kwan, J.; Chiu, P.; Yau, J.; Lam, L. Psychophysiological Effects of Dance Movement Therapy and Physical Exercise on Older Adults with Mild Dementia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The journals of gerontology. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, C.M.; de Mattos Pimenta, C.A.; Cuce Nobre, M.R. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. De Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascaes da Silva, F.; Valdivia Arancibia, B.; da Rosa, R.; Barbosa, P.; Silva, R. Escalas y listas de evaluación de la calidad de estudios científicos. Rev. Cuba. De Inf. En Cienc. De La Salud 2013, 24, 295–312. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2307-21132013000300007&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- De Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, R.; Moseley, A.; Sherrington, C.; Maher, C. Physiotherapy Evidence Database. Physiotherapy 2000, 86, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, L.; Paludan-Müller, A.S.; Laursen, D.R.; Savović, J.; Boutron, I.; Sterne, J.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Hróbjartsson, A. Evaluation of the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized clinical trials: Overview of published comments and analysis of user practice in Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguiñaga, S.; Ehlers, D.K.; Salerno, E.A.; Fanning, J.; Motl, R.W.; McAuley, E. Home-Based Physical Activity Program Improves Depression and Anxiety in Older Adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 692–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque-Martínez, M.A.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Artés-Rodríguez, E.M. Efectos de un programa de ejercicio físico multicomponente sobre la condición física, la autoestima, la ansiedad y la depresión de personas adultas-mayores (Effects of a multicomponent physical exercise program on fitness, self-esteem, anxiety and depres). Retos 2021, 39, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbón-Castro, N.A.; Castro-Zamora, A.A.; Cruz-Castruita, R.M.; Banda-Sauceda, N.C.; De La Cruz-Ortega, M.F. The Effects of a Multidimensional Exercise Program on Health Behavior and Biopsychological Factors in Mexican Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; Moore, K.A.; Craighead, W.E.; Herman, S.; Khatri, P.; Waugh, R.; Napolitano, M.A.; Forman, L.M.; Appelbaum, M.; et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escolar Chua, R.L.; de Guzman, A.B. Effects of Third Age Learning Programs on the Life Satisfaction, Self-Esteem, and Depression Level among a Select Group of Community Dwelling Filipino Elderly. Educ. Gerontol. 2013, 40, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Konopack, J.F.; McAuley, E.; Elavsky, S.; Jerome, G.J.; Marquez, D.X. Depressive symptoms among older adults: Long-term reduction after a physical activity intervention. J. Behav. Med. 2005, 28, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. The effects of 16-week group exercise program on physical function and mental health of elderly Korean women in long-term assisted living facility. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2009, 24, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Zhao, X.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Yang, C.; Yang, F. Prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 311, 114511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Vogelzangs, N.; Twisk, J.; Kleiboer, A.; Li, J.; Penninx, B.W. Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Kling, J.M. Depression and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Death: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Medicine 2016, 95, e2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotella, F.; Mannucci, E. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for depression. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 99, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalat, G.; Plasse, J.; Gauthier, E.; Verdoux, H.; Quiles, C.; Dubreucq, J.; Legros-Lafarge, E.; Jaafari, N.; Massoubre, C.; Guillard-Bouhet, N.; et al. The central role of self-esteem in the quality of life of patients with mental disorders. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; Heinsch, M.; Betts, D.; Booth, D.; Kay-Lambkin, F. Barriers and facilitators to the use of e-health by older adults: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinas, P.C.; Koutedakis, Y.; Flouris, A.D. Effects of exercise and physical activity on depression. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 180, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toros, T.; Ogras, E.B.; Toy, A.B.; Kulak, A.; Esen, H.T.; Ozer, S.C.; Celik, T. The Impact of Regular Exercise on Life Satisfaction, Self-Esteem, and Self-Efficacy in Older Adults. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Merwin, R.M. The Role of Exercise in Management of Mental Health Disorders: An Integrative Review. Annu. Rev. Med. 2021, 72, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, F.D.; Stein, J.; Röhr, S.; Fuchs, A.; Pentzek, M.; Mösch, E.; Bickel, H.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Wiese, B.; et al. Prevalence of Anxiety Symptoms and Their Association with Loss Experience in a Large Cohort Sample of the Oldest-Old. Results of the AgeCoDe/AgeQualiDe Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L.; Araújo, L.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Forjaz, M.J. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Trajectories of Influence across Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorston, L.C.; Kolt, G.S.; Rosenkranz, R.R. Physical activity and physical function in older adults: The 45 and up study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahindru, A.; Patil, P.; Agrawal, V. Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e33475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key Words | PubMed | SciELO | WoS | Scopus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Older adults” OR “Elderly” AND “Physical activity” OR “Physical Exercise” AND “Depression” AND “Self-esteem” | 52 | 01 | 66 | 37 |

| Authors | Subjects | Study Design/Objective | Duration of the Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aguiñaga et al. [29] | A total of 307 older adults. FTB group (113 women and 45 men) and control group (123 women and 26 men). | Quasi-experimental: To examine the effect of a DVD-delivered exercise intervention on secondary outcomes of depression and anxiety in older adults and the extent to which physical self-esteem mediated the relationship between leisure-time physical activity and depression and anxiety. | 6 months |

| Araque-Martínez et al. [30] | A total of 70 older adults (65 women and 5 men). | Pre-experimental: To analyze the effects of a multicomponent exercise program on physical fitness, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression in older adults. | 8 months |

| Borbón-Castro et al. [31] | A total of 45 older adults (22 in the control group and 23 in the experimental group). | Quasi-experimental: To investigate the effects of participation in a 12-week multidimensional exercise program on the health behavior and psychological factors of older adults living in northeastern Mexico. | 12 weeks |

| Blumenthal et al. [32] | A total of 156 men and women (exercise group: 53; antidepressant medication group: 48; exercise and medication group: 55). | Randomized controlled trial: To evaluate the effectiveness of an aerobic exercise program compared with standard medication for the treatment of major depressive disorders in older adults. | 16 weeks |

| Escolar and De Guzman [33] | A total of 40 older adults (15 older adults in the control group and 25 older adults in the experimental group). | Quasi-experimental: To assess the effectiveness of community-based learning programs for the elderly on life satisfaction, self-esteem, and depression level of a selected group of elderly Filipinos in a community setting. | 4 months |

| Motl et al. [34] | A total of 174 men and women (walking group: 85 seniors; muscle-strengthening group: 89 seniors). | Randomized controlled trial: To evaluate the effectiveness of an exercise intervention for the sustained reduction in depressive symptoms among sedentary older adults and physical self-esteem as a potential mediator of this effect. | 6 months |

| Sung [35] | A total of 37 women > 65 years (16 women aged 65 to 75 years and 21 women > 75 years). | Randomized controlled trial: To compare the effects of a 16-week group exercise program on physical function and mental health of older women with younger older women. | 16 weeks |

| Authors | Intervention | Frequency | Analysis | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguiñaga et al. [29] | Physical exercise through DVDs (FlexToBa). | No mention of weekly frequency. | HADS; Godin’s Leisure Time; Exercise Questionnaire; PSW. | Self-esteem ↑ Depression ↓ Anxiety ↓ |

| Araque-Martínez et al. [30] | Tasks designed to work on physical, cognitive, and/or emotional levels through movement. | Two sessions of 1 h per week. | SFT; Test de Rosenberg; HADS. | Fitness ↑ Self-esteem ↑ Anxiety ↓ Depression ↓ |

| Borbón-Castro et al. [31] | An exercise program based on improving aerobic capacity, muscular strength, speed, agility, flexibility, and coordination. | Five days a week for 1 h. | GDS-15; Test de Rosenberg. | Self-esteem ↑ Depression ↓ |

| Blumenthal et al. [32] | A treadmill walking or jogging program. | Three days a week for 50 min. | HAM-D test; Rosenberg test; BDI test; Aerobic capacity. | Depression ↓ Self-esteem ↑ Anxiety ↓ Aerobic capacity ↑ |

| Escolar and De Guzman [33] | A physical conditioning program based on muscular strength and cardiovascular endurance. | One session per week lasting between 30 and 40 min. | Test de Rosenberg; GDS-15; LSITA-SF test. | Depression ↓ Self-esteem ↑ Level of life satisfaction ↑ |

| Motl et al. [34] | A walking program focused on cardiovascular endurance or muscular flexibility and strength. | Three times per week, from 10 min to 45 min. | GDS-15; PSPP. | Depression ↓ Self-esteem ↑ |

| Sung [35] | A functional exercise program combined with health education. | Three times a week for 40 min. | Rosenberg Test; GDS-15; Sit And Reach Test; Standing on one leg with eyes open and closed (balance); Sitting and standing on a chair for 30 s. | Functionality ↑ Flexibility ↑ Strength ↑ Self-esteem ↑ Depression ↔ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz Pinto, M.; Montalva-Valenzuela, F.; Farías-Valenzuela, C.; Ferrero Hernández, P.; Ferrari, G.; Castillo-Paredes, A. Effects of Physical Activity or Exercise on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Esteem in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020046

Muñoz Pinto M, Montalva-Valenzuela F, Farías-Valenzuela C, Ferrero Hernández P, Ferrari G, Castillo-Paredes A. Effects of Physical Activity or Exercise on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Esteem in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz Pinto, María, Felipe Montalva-Valenzuela, Claudio Farías-Valenzuela, Paloma Ferrero Hernández, Gerson Ferrari, and Antonio Castillo-Paredes. 2025. "Effects of Physical Activity or Exercise on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Esteem in Older Adults: A Systematic Review" Psychiatry International 6, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020046

APA StyleMuñoz Pinto, M., Montalva-Valenzuela, F., Farías-Valenzuela, C., Ferrero Hernández, P., Ferrari, G., & Castillo-Paredes, A. (2025). Effects of Physical Activity or Exercise on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Esteem in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry International, 6(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6020046