1. Introduction

Psychosis is a clinical syndrome that has several key features which interact with one another to cause individuals distress which can result in acute inpatient admission and/or sometimes, depending on severity, prolonged residential stays within rehabilitation and recovery units [

1]. Psychosis can occur at any point within the lifespan; however, it tends to occur earlier in males than for females, with males usually contracting symptoms in late adolescence, early adulthood compared to females who often appear to begin showing symptoms between early and mid-adulthood [

2]. In Ireland, the syndrome has an incidence rate of 25.62 per 100,000 population with this incidence increasing two-fold for migrants entering the country [

3].

The number of people in Irish psychiatric units have steadily declined in the past couple of decades [

4]. In 2019, this figure was 2308, showing a hospitalisation rate for those with mental health challenges of 48.5 per 100,000 [

4]. One third of these hospitalisations can be traced back to a psychotic related illness/disorder, suggesting a severe burden on acute mental health services in Ireland [

4]. To help alleviate this burden and to reduce severe relapse for those with psychosis, the Early Intervention in Psychosis [EIP] model of care for Ireland was developed, which like policy, also supported the move towards a more community-based model of interventions and support for those experiencing psychosis.

1.1. Early Intervention in Psychosis

EIP is a clinical programme that applies to individuals who are experiencing their first episode of psychosis within the age periods of 14 to 65 years [

5]. For those with at risk mental state [predetermined clinical features of emerging/prodromal schizophrenia identified in young people] the age limit is 14 to 35 years [

6]. Individuals presenting with first episode psychosis should have access to EIP services for up to three years. It excludes confirmed organic psychotic disorders as they can be more appropriately managed by medical services.

The programme’s vision is that everyone who develops psychosis for the first time or is identified as being at risk of developing psychosis receives the highest quality of care and treatment to achieve their optimal clinical, functional, and personal recovery [

5]. The importance of the service user leading out on their care plan is central. This should be supported by informed clinical best practice and an understanding of the person’s lived experiences.

The key aims of this service are (1) the early detection of first episode psychosis and at-risk mental state (2) the provision of standardised assessments for the duration of the EIP programme and (3) the provision of standardised evidence based biopsychosocial interventions in a timely manner to individuals who meet the inclusion criteria for the programme [

5].

Early detection and reducing delays to diagnosis and to evidence-based assessments and treatment with well-resourced and trained multidisciplinary teams has the potential to reduce illness severity and improve outcomes [

7]. The services should instil an ethos of hope in recovery for service users and their families/carers. All aspects of service development, training and research should include co-production with service users and carers.

Interventions will include individually tailored medication regimes, physical health monitoring and lifestyle interventions, specific psychological therapies, and family interventions. All of which work towards recovery with engagement in appropriate social, educational, and occupational interventions [

8].

While it is expected that over time the personal, societal, and service cost will reduce there is a requirement to invest significantly in personnel and training at the beginning. On a personal level this should lead to better symptomatic and functional recovery, with increased satisfaction and more engagement with relevant services. Additionally, there will be less use of hospital beds, incidence of involuntary admissions, suicide, and a higher rate of future employment for such individuals [

9].

Whilst psychiatrists are beginning to learn a lot more about the causes of mental illness, simultaneously the value of experiential knowledge is beginning to be realised. Experiential knowledge is knowledge learned not via pedagogical means. Rather it is knowledge acquired through experiences of having and living with a mental illness. This knowledge has grown in importance in recent years due to the rise of the recovery movement. The recovery movement does not view an individual by their deficits. Rather, it looks at the person’s strengths to facilitate conversations that will ultimately allow individuals to figure out for themselves what recovery means to them. It is not the reduction of signs and symptoms of disease. Rather it is a re-enchantment with life as one learns to grow beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness [

10,

11]. The value of such experiences is now so powerful that it is engrained in policy and slowly becoming prominent in practice [

12,

13].

In recent years, such knowledge has been valuable in educating clinical staff, with many students positively expressing an enhanced learning experience resulting from the sharing of lived experiences [

14]. This was made possible by bringing to life, medical text through the implementation of peer academics. Most research into this enhanced learning experience through peer input have been qualitative in nature, mainly by Australian scholars such as Brenda Happell. Findings to date suggests positive impacts on the learning for such students interviewed [

15,

16,

17,

18] However, there has been a noted need for further study in order to fully understand this co-produced, learning initiative [

15,

18]. Such positive experiences were also cited by service users employed in peer academic roles and traditional academics [

19,

20,

21].

1.2. Rationale for Paper

The creation of this paper resulted from a workshop on EIP interventions co-produced by the first author [MJN] and another psychiatrist with specific interest in EIP. One author [MJN] has lived experience of psychosis whereby the other [MMcL] is Clinical Director for an Irish mental health service and consultant psychiatrist for a Psychiatry of Later Life [PoLL] service. The workshop that enlightened this article was co-produced as part of a clinical training programme for trainee psychiatrists necessary as part of their training syllabus with the College of Psychiatrists in Ireland. Its intention was to introduce the concept of psychosis as a powerful, overarching syndrome of disease whilst also giving insight into psychosis from a lived experience perspective. Resulting from this workshop, the first author identified a gap in current literature which this article will address. As such, the aim of this article is to provide a more complete understanding of psychosis through personal accounts from lived and professional experience perspectives. In order to achieve this aim, the following objectives were required:

To gather autobiographical experiences of psychosis so that the lived experience of the syndrome and how it impacts a person’s entire life is presented.

To discuss the learned knowledge relating to psychosis

To provide a reflection of the role of psychiatry in the diagnosis and treatment of psychosis and finally.

To provide a list of recommendations for the clinical teaching and practice of psychiatry based on the fusion of experiences.

3. The Clinical Perspective

Psychotic features occur in several conditions, the most common being schizophrenia, mood disorders, delirium, personality disorders and organic brain disease including epilepsy or intoxication by certain substances. What causes some people to become psychotic and not others remains unclear. There are probably several mechanisms at play including genetic predispositions and environmental factors such as trauma, chronic stress or substance misuse, with different combinations being relevant for different people.

A genetic basis for mental illness has been investigated since early last century. Looking specifically at schizophrenia, genetic linkages were identified through twin studies conducted by Kallmann in 1946 [

24]. The evidence base for this assumption is growing with individuals like Henriksen and colleagues [

25] still investigating same to this day through detailed reviews. In 2010 the results of the Human Genome project were published, which instilled hope among clinicians that a genetic basis for mental ill health would be determined. However, they found that there are many different genetic permutations linked to mental illness and no single genetic code was associated with mental illness [

26]. Additionally, other investigations in the past number of years have found specific genetic genome markers associated with mental illness, particularly around schizophrenia [

27,

28,

29].

There is evidence that the structure of the brain is different in service users with a schizophrenic illness, which is not noted to the same extent in other psychotic illnesses [

27]. The relevance of this to psychotic presentations is still not clear. Modern scanning methods have given us a much greater ability to understand how the brain works and also gives some insight into what happens in the brain when people develop symptoms of mental illness. Scans not only show the structures of the brain, but they also provide information on blood flow and how cells in the brain use energy. Even simple actions such as picking up a pen or listening to music can demonstrate to the observer what pathways the individual is using during functional scanning.

Aside from showing lesions in the brain, that in rare instances can cause psychosis, they can also show how volumes in different parts of the brain can decrease during psychotic episodes. Scans can highlight areas of increased metabolism during psychosis. Unfortunately, while such findings are becoming more refined, they do not have the ability to significantly aid diagnosis in day-to-day clinical practice [

28].

There are also theories suggesting that people with schizophrenia might be unable to process the information their central nervous system gathers, which can cause an individual to become overwhelmed. This inability to process large volumes of information is known as the theory of sensory gating [

29].

The over or under production of several neurotransmitters have also been identified as a potential cause of psychotic symptoms. The most commonly mentioned is Dopamine. Carlsson and Lindqvist [

30] first suggested that blocking the dopamine receptor was the basis for the effect of antipsychotic medication. However, some of the benefits of antipsychotic medication seem to come from the opposite effect. Other neurotransmitters such as Glutamate, Serotonin and Nicotinamide have also been implicated in the development of psychosis.

In terms of treatment for the syndrome, there is an array of treatment options available. The first port of treatment, as partly discussed above is through the use of antipsychotics. There are two types of antipsychotics: conventional and atypical antipsychotics [

31]. Both of which interact with various neurotransmitters in the brain to reduce hallucinations, a common feature of psychosis. In addition to medication, there are a number of psychological therapies and self-help/educational programmes that are useful in the treatment of psychosis including cognitive behavioural therapy, Wellness Recovery Action Planning and, in an Irish context, EOLAS [

32].

A Psychiatrist’s Experience

Psychiatrists are trained to take a thorough history from a service user and do a detailed mental state examination. The history taking should include relevant collateral history. As doctors, we look to rule out physical health issues that may complicate the clinical picture. We develop a biopsychosocial formulation based on the information gathered, consider the potential diagnoses and, preferably in collaboration with the service user, put a plan of care in place.

My experience is that people with psychosis present with a story and symptoms that have a commonality with other people who present with psychosis. However, every person is an individual and their story is always their own. The psychotic symptoms they experience fall into categories such as hallucinations, delusional beliefs, thought disorder but how these symptoms interact and how the individual deals with these symptoms varies.

I believe that as clinicians we need to listen to each service user and try to tailor their treatment to the individual. This is with an acceptance that the treatments available to psychiatrists and service users are often quite broad based and this can make tailoring them in an individual way challenging at times. The pathway to recovery for a teenager may look quite different to that of a person who develops a psychotic illness when they are in employment and maybe have a longstanding relationship or children.

4. The Lived Experience Perspective

The following is a reflection of an author’s [MJN] lived experiences of psychosis. For ease of description, the lived experiences of psychosis are first separated into three distinct but connecting features. The auditory experience describes the lived experiences of voice hearing. The visual experience describes the lived experiences of observing phenomena which are not present within reality. Finally, the delusions describe the fixed beliefs that were created and the impact this has had on the service user. Additionally, for the total experience to be recognised, this paper concludes by describing the culmination of experiences along with the somatoform features that such culmination creates. It is important to note that this is entirely the named author’s experience of psychosis, however it is hoped that this experience will showcase the complexity of what happens to individuals when they present to services with psychosis.

4.1. The Auditory Experience

The experience of auditory hallucinations is a hallmark symptom of psychosis [

33]. It describes a sensory experience that occurs without the presence of an external source or stimulus [

34]. The experience of auditory hallucinations first began in 2010. This was meant to be an exciting time as the author had left home for the first-time and as such, everything was new for him. However, instead of enjoying this new-found experience, he was scared of it. The rationale for this came from a strange voice that resided within the author’s head.

This strange voice was negative in nature, that in some ways sounded like the author’s voice but mixed with that of a stranger’s voice. The voice was male and always angry. As the individual became even more unwell, this one voice was accompanied by two other voices [one male and one female] which made it even harder to fight off and ignore. All voices were extremely negative in nature and conflicting, creating a world of confusion. From the author’s perspective and for ease of clarity, they are depicted here as three black figures sitting in the centre of the brain looking out on the world through the victim’s eyes (

Figure 1).

It is difficult to describe the internal dialogue and communication strategies of these voices but imagine a world where every waking moment is surrounded by constant internal criticism. Such criticism was particularly distressing in times of crisis. However, in times of wellness, three voices are reduced to the one male voice who presents himself sporadically. The confusion created by three critical and conflicting voices at times of crisis is partly what led to an altered sense of reality, remnants of which still remain today.

In the author’s experience, these voices interact with the service user for two reasons: a bet and/or a command. A bet is exactly what it says on the tin: a bet. The inspiration for which often came from the simplest of things, but the consequences of losing the bet were dire. The bargaining chip was often something spiritual, usually a soul, in particular the author’s soul. Whether it be that this soul goes to hell or be taken out of the host and implanted into an animal ready for slaughter. It was never nice and as explained later, there was a compulsion to go along with these bets. Waiting for the eventual outcome which would determine the bet maker’s eternal fate. A command on the other hand was slightly different. The voices would make you carry out the most deplorable acts. The content of such acts can consist of anything from the simple everyday tasks like washing hands to saying horrible things to friends and family to deviant and risky behaviour relating to my sexuality. However, commands could also consist of other acts of self-harm that all would result in the person’s eventual social, spiritual, and personal demise.

4.2. The Visual Experience

Visual hallucinations are visual perceptions that are present whilst conscious without an external stimulus [

35]. They are more commonly associated with organic brain disease, such as lewy body dementia, but can also result from psychiatric disease [

36], with an incidence of 26.5% for those suffering from a psychotic illness [

37]. The initial experience of the author lacked visual hallucinations. However, as the disease progressed towards crisis and hospitalisation, their presence became evidently noted. From the author’s own experiences, these hallucinations can come in three different ways: dots, visions, and shadows.

Since the first hospitalisation, the way this service user viewed the world had changed utterly. In his reality, everything is made up of small dots which can come together to form an object, liquid or gas. Everything from the sky, to people, to food, to objects, are all made up of dots. These dots on their own could never cause harm or fear. However, it is when these same dots form inanimate objects that their potential for fear and harm escalates. This normally occurs during times of great stress and even unwellness. It is when these dots become inanimate objects that they become known as shadows.

Shadows have the ability to be 2D in the form of a normal shadow on a wall or 3D where they occupy their own space. They are called shadows as they are black in colour. Sometimes they can be mere black blobs that float independently in the air. Other times, particularly when unwell, they can take the shape of dragons, knights on horses, cattle and so on.

Over the years, these dots have supported this particular service user in managing their wellness and is now a key feature of his Wellness Recovery Action Plan—a structured programme for anyone who wants to create positive change in their lives [

38]. Now, if small dots are observed, it means he is in a place of wellness. This is now his norm. However, when these dots begin to grow and form inanimate objects/creatures, this is an early warning sign which tells him that he needs take appropriate action to protect his wellness.

In the ten or so years this author has lived with psychosis, he has only experienced visions a handful of times, all of which occurred during times of crisis. Visions describe an out of body experience where the individual is transported to another world that has some basis in reality. For example: the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York. During such visions, two possible scenarios can occur. The author is either in the cockpit at the moment of impact with the World Trade Center or is actually in the building, on the exact floor at the exact moment of impact. Regardless of the scenario, the ending is always the same. Suddenly, in what feels like eternity, but in reality, a millisecond, he is transported from the red of fire and blood back to a few moments before penetration and the cycle begins again. Due to the pure distress caused by these experiences, inpatient treatment is often required.

4.3. The Delusions

There is no universally accepted definition for delusions in the academic literature [

39,

40]. Instead, delusions are identified by their clinical presentations. For instance, Kiran and Chaudhury [

41] defines the term based on its clinical features and not the delusional content itself. Here, they suggest that a delusion is:

“…a belief that is clearly false and that indicates an abnormality in the affected person’s content of thought… is not accounted for by the person’s cultural or religious background or his or her level of intelligence.”

For the author, he first experienced delusions just before his first hospitalisation. The content of these delusions centred around the end of the world and more importantly, the service user’s part in that process. The delusions were intrinsically linked to the voices of that time. The main idea of the delusion was that one was responsible for every human soul in this world and that individual actions or inactions alone will result in the planet’s demise. Additionally, these delusions were exacerbated by the religious beliefs of the author at that time. As a result of this, a second delusion emerged where the individual was an evil priest who sexually assaulted children.

Although, the above examples are bizarre, at that time they were totally plausible, believable and factual. This may be because they had some ties with reality, but neither were true. In terms of the delusion pertaining to Armageddon, this was tied to my enjoyment of disaster films and the sense of responsibility the individual had acquired through their professional work as a student general nurse. Equally in terms of the evil, paedophile priest, this was tied to the author’s supressed sexuality. It relates to a memory experienced years ago when this individual first realised, he was gay. During such conflicting times, the author remembers an internal dialogue within his brain where he suggested that he would rather become a priest than admit to himself and the world his sexual orientation. Additionally, it also tied to a media focus in the early 2000′s where priests in Ireland were being identified, charged, and convicted of the sexual abuse of minors in their care.

These delusions were significant in my care as they were signs to others that the author was in a state of extreme unwellness and required hospitalisation to untangle these belief systems. However, in the long term the author has started to experience some residual effects of such delusions. He still cannot go to mass and practice his faith. He still cannot watch disaster films and he questions himself whenever he holds an office of responsibility. Work on overcoming this is still ongoing today, some ten years after the original fixed beliefs began.

4.4. Recipe for Disaster—The Fusion of Experiences

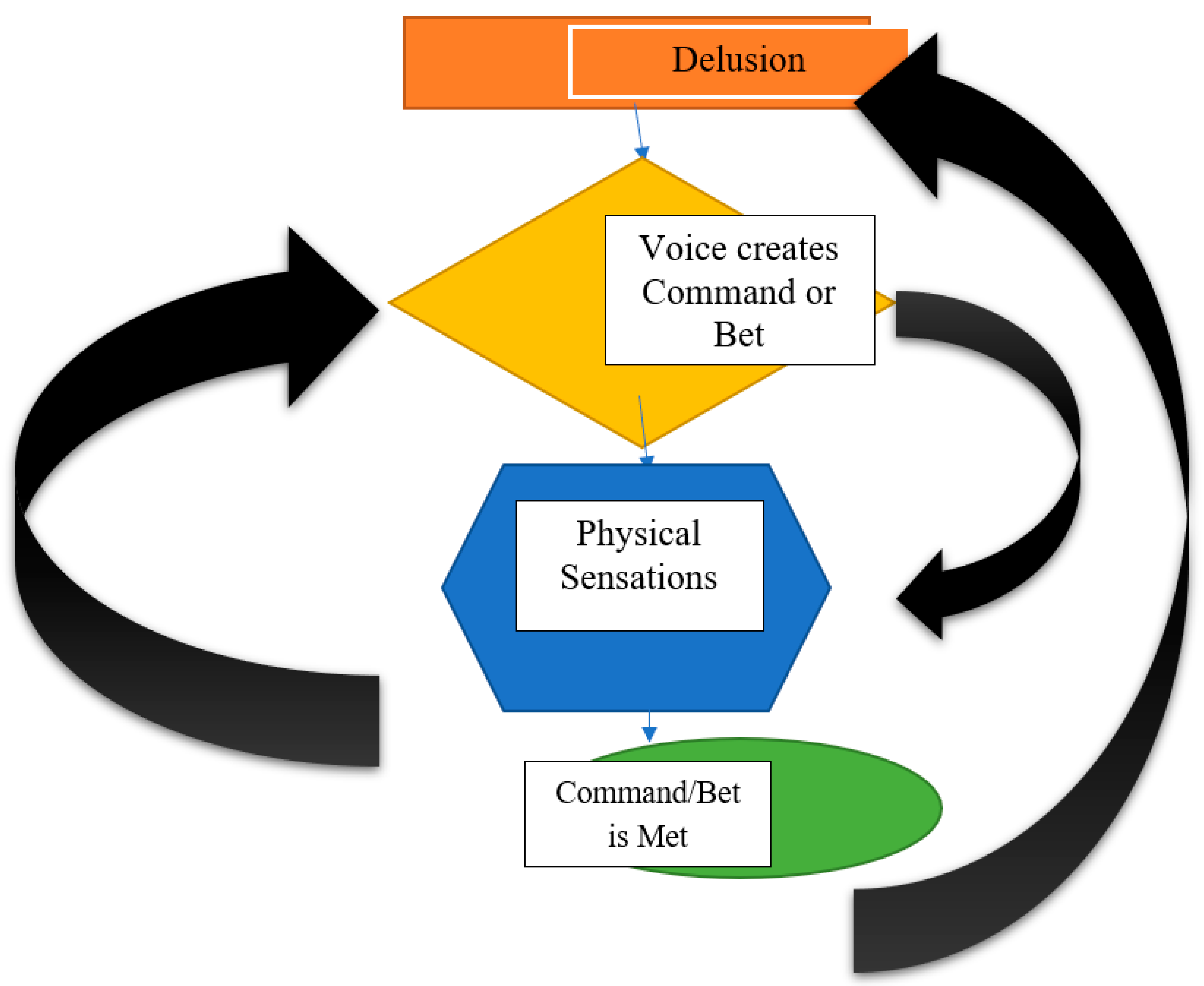

Any one of these experiences would cause extreme distress. However, for the author, it was the fusion of the three that resulted in a psychotic break. From his experiences, these three areas work together under a positive feedback loop (

Figure 2) allowing each element to influence the other. For this section, the physical experiences and their relationship with the above created a recipe for disaster where the author lost control over his life to such an extent that he contemplated suicide on numerous occasions.

In the author’s experience, when he is in an acute phase of psychosis, the delusional beliefs do influence the context of the voices’ command or bet. This resulted in the creation of an array of physical symptoms. As illustrated in

Figure 2, these physical sensations can cause the voices to intensify their commands/bets which undoubtedly would cause further intense physical experiences. The idea here is that this loop would continue until the command is completed or the outcome of the bet is determined. Once this happens, within a matter of seconds, the loop begins again with a communication sent between the delusion and the voices.

As stipulated above, over the last ten years living with psychosis, an array of physical symptoms was experienced that resulted directly from a command/bet being made. These physical symptoms were most prevalent around the head, chest and abdomen. In terms of the head, the service user in question would literally feel the cerebral spinal fluid [CSF], naturally present within the brain move rapidly and with intensity. This rapid and intense movement goes in a circular motion around the brain which causes the brain to feel constricted from the movement of the fluid. This motion also would lead to headaches, decreased concentration and at times, could result in a shadow forming as such volatile movements reached the visualisation centre of the brain. In terms of the chest, the physical symptoms experienced are like that of anxiety. The author would feel a tightness in his chest as if it was being crushed by a foreign object. This resulted in shortness of breath. However, the most frequent physical symptom that he would have experienced occurs on the top of the abdomen. Here, from the moment a command or bet was made, until the outcome was determined, this service user would often feel a tightness in his stomach which most people would relate to as having butterflies in their stomachs. However, additional to this, he would also experience a deep fire in his gut. As if everything was burning. This feeling intensified to the point where it would become unbearable and thus, at that moment, the command would be achieved. When it came to a bet, this fire would remain aflame until the result of the bet was determined.

At first, these physical symptoms may have resulted from the deviant acts the voices forced this individual to do over the course of his ill health. However, on reflection, it seems more likely that these physical symptoms symbolised the suppression of a true self that was trapped due to religious beliefs and the societal norms evident in rural Ireland at that time.

6. Conclusions

This paper was developed as an attempt to combine both the clinical and experiential knowledge as it pertains to psychosis. Psychosis has been defined as a clinical syndrome that can occur from a variety of different physical and mental health conditions. However, through the input of those with lived experience, we were able to demonstrate just how psychosis impacts on an individual’s quality of life. From the use of autoethnographic approaches, we learned that the symptoms of psychosis can affect every aspect of a person’s life—the spiritual, the psychological, the behavioural and finally the physical self. Resulting from this fusion of knowledge subsets, several recommendations were then made to support services to provide care that is co-produced and individualised to each service users’ needs. However, more analysis of the actual experiences of psychosis is warranted and should be incorporated into future qualitative studies examining the syndrome itself.

This article adds to the scientific literature regarding psychosis as it is the first, to the authors knowledge, to fuse both the learned and experiential knowledge as it relates to psychosis. This is necessary and timely as psychiatry as a discipline is now becoming more open to views and perspectives of its service users. The addition of this article to the scientific community further supports the growth in value for lived experience in mental health care. In doing so, this article puts on paper, the benefits that are observed on a daily basis from having lived experience input both within multi-disciplinary teams and in the co-production of recovery education initiatives.