Trust in News Media Across Asia: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual and Societal Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Individual-Level Causes of News Media Trust

2.1.1. Individual Capital and News Media Trust

2.1.2. Cultural Values and News Media Trust

2.2. Societal-Level Causes of News Media Trust

3. Method

3.1. Data

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Individual-Level Measures

3.2.2. Society-Level Measures

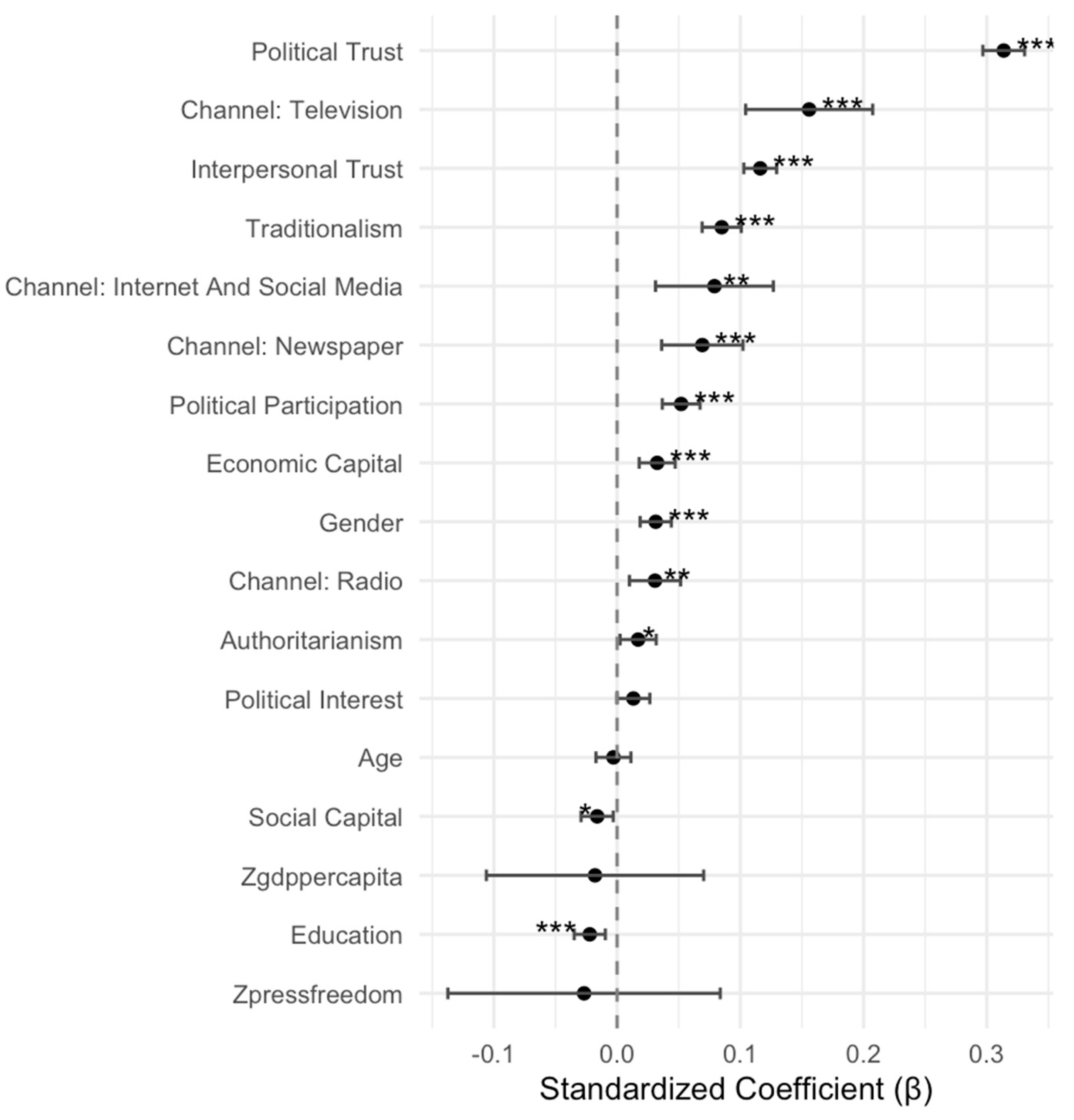

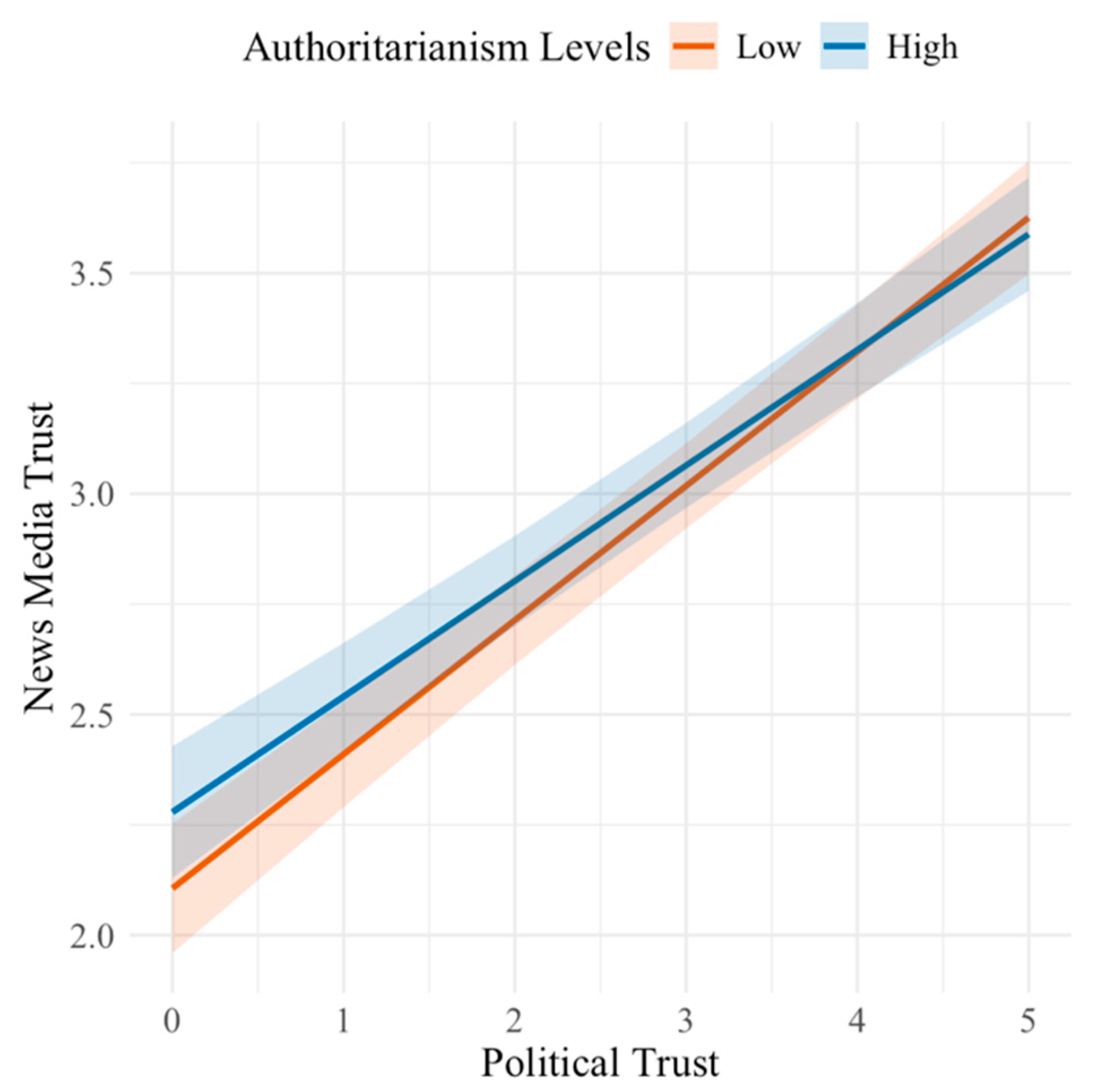

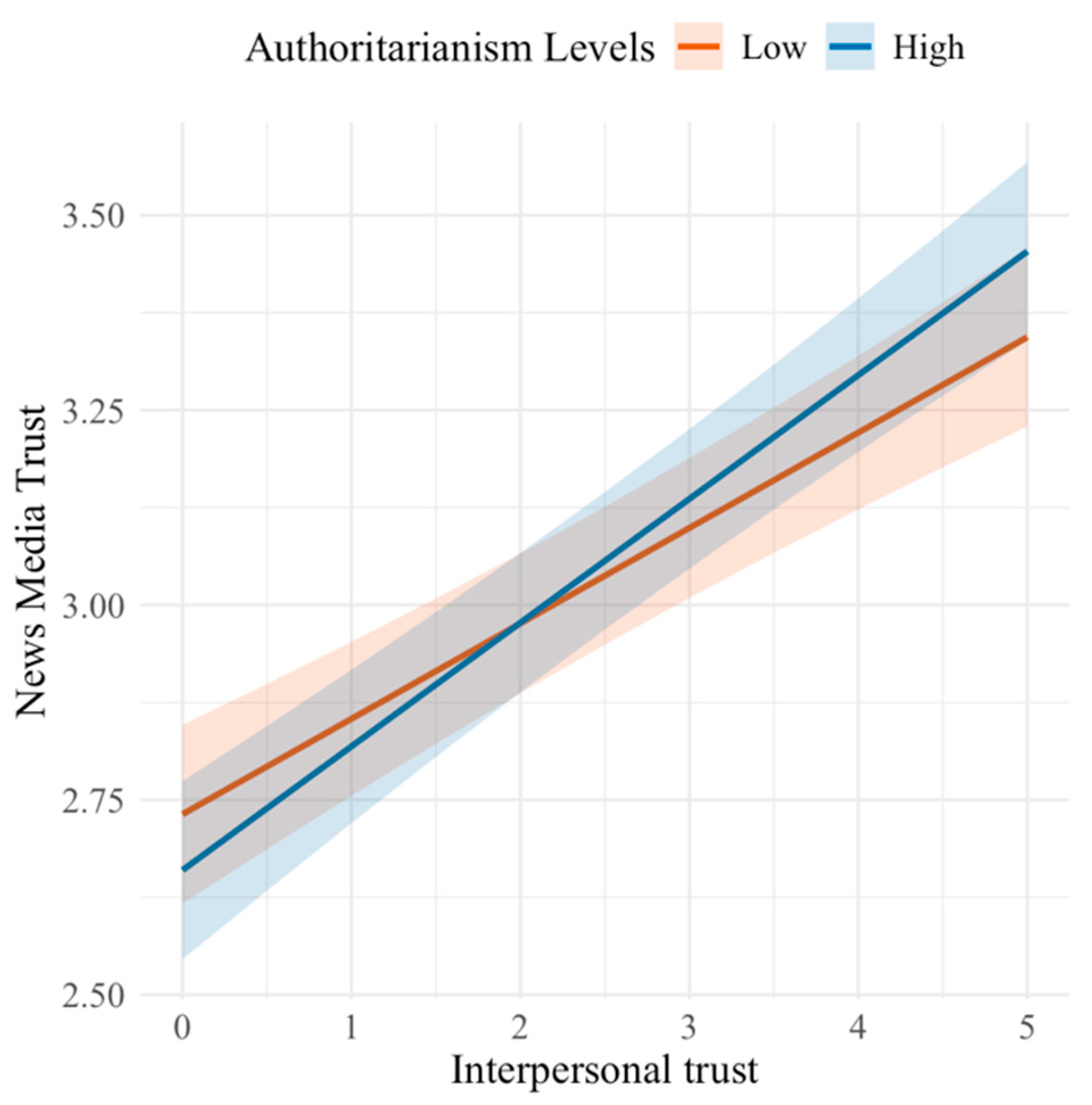

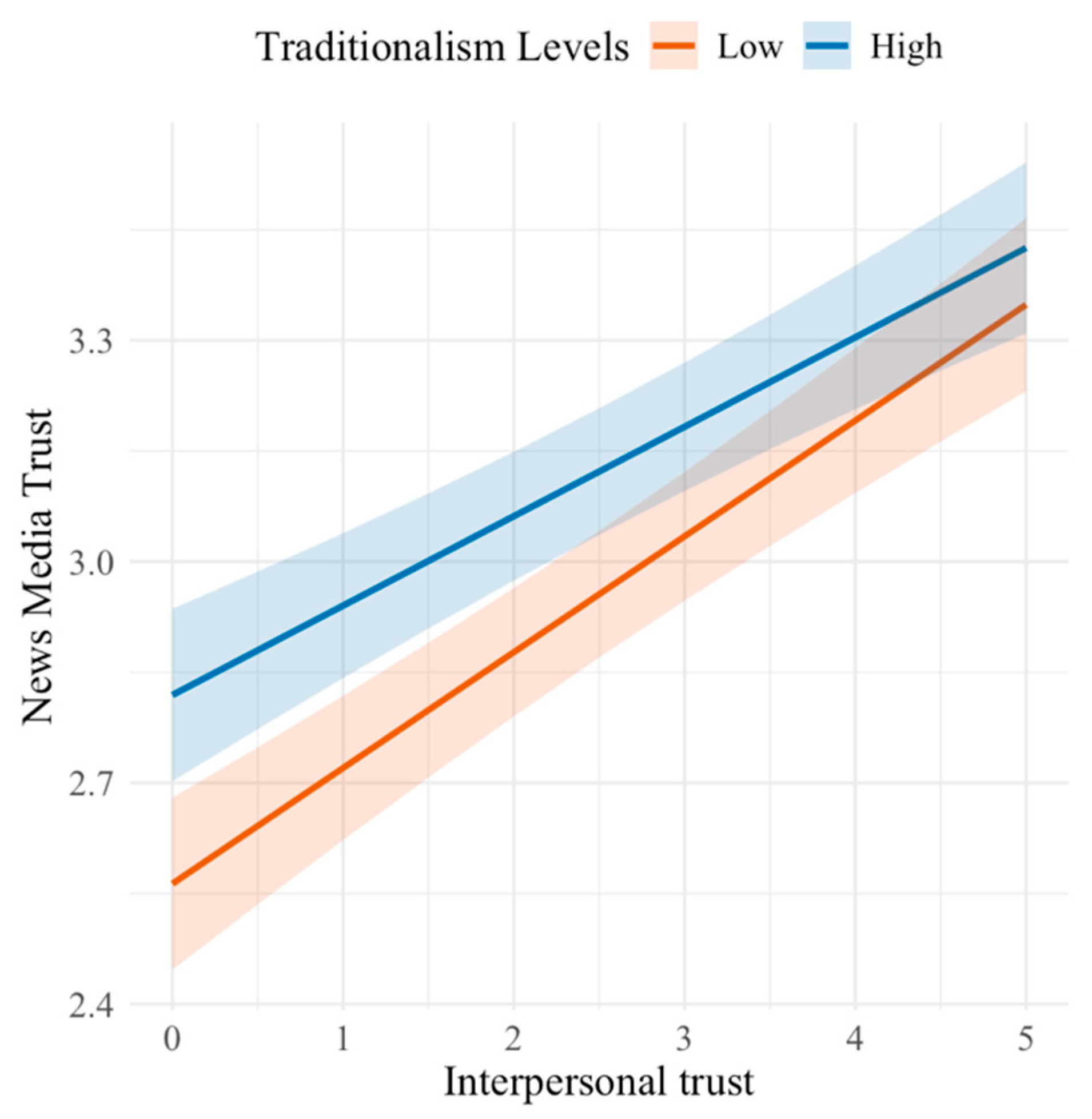

4. Results

Robustness Checks

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Cross-National Societal-Level Variables

| Country ID | Country Name | World Press Freedom 2019 | GDP per Capita 2019 (Current US $) |

| 1 | Japan | 70.64 | 40,416.00 |

| 2 | Hong Kong | 70.35 | 48,359.00 |

| 3 | Korea | 75.06 | 31,902.40 |

| 4 | China | 21.08 | 10,143.90 |

| 5 | Mongolia | 70.49 | 4394.90 |

| 6 | Philippines | 56.09 | 3413.80 |

| 7 | Taiwan | 75.02 | 25,908 |

| 8 | Thailand | 55.9 | 7628.60 |

| 9 | Indonesia | 63.23 | 4151.20 |

| 10 | Singapore | 48.59 | 66,081.70 |

| 11 | Vietnam | 25.07 | 3491.10 |

| 12 | Cambodia | 54.1 | 1671.40 |

| 13 | Malaysia | 63.26 | 11,132.10 |

| 14 | Myanmar | 55.08 | 1415.20 |

| 18 | India | 54.33 | 2050.20 |

| Note. data source: 2019 World Press Freedom Index: Reporters Without Borders, RSF. https://rsf.org/en/index (accessed on 13 January 2025); 2019 GDP per capita: WORLD BANK GROUP, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2019&start=1960 (accessed on 13 January 2025); 2019 GDP per capita: WORLD BANK GROUP, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2019&start=1960 (accessed on 13 January 2025); National Statistics, R.O.C. (Taiwan), https://nstatdb.dgbas.gov.tw/dgbasAll/webMain.aspx?k=dgmain (accessed on 13 January 2025). | |||

Appendix B. Variable Measurement and Coding

| Variable Name | Question Wording | Option | Code | Recoded |

| Media trust | How much trust do you have in each of the following types of media? 53. Television 54. Newspaper 55. News on the internet | Trust fully | 1 | 5 |

| Trust a lot | 2 | 4 | ||

| Trust somewhat | 3 | 3 | ||

| Distrust somewhat | 4 | 2 | ||

| Distrust a lot | 5 | 1 | ||

| Distrust fully | 6 | 0 | ||

| Economic capital | 4. As for your own family, how do you rate the economic situation of your family today? | Very good | 1 | 4 |

| Good | 2 | 3 | ||

| So-so | 3 | 2 | ||

| Bad | 4 | 1 | ||

| Very bad | 5 | 0 | ||

| 5. How would you compare the current economic condition of your family with what it was a few years ago? Is it … 6. What do you think the economic situation of your family will be a few years from now? Will it be … | Much better now | 1 | 4 | |

| A little better now | 2 | 3 | ||

| About the same | 3 | 2 | ||

| A little worse now | 4 | 1 | ||

| Much worse now | 5 | 0 | ||

| Social capital | 28. How many people do you have contact within a typical week day? | 0–4 people | 1 | |

| 5–9 people | 2 | |||

| 10–19 people | 3 | |||

| 20–49 people | 4 | |||

| 50 or more people | 5 | |||

| 29. Which of the following best describes your relations with most of your social contacts? | Most people’s social status are higher than yours | 1 | 1 | |

| Most people’s social status is lower than yours | 2 | 3 | ||

| Most people’s social status are equal to yours | 3 | 2 | ||

| 30. Among these people you have frequent contacts, which of the following best describes the political views of these people? | Virtually all of them have views similar to me | 1 | 4 | |

| A lot of them have views similar to me | 2 | 3 | ||

| Only some of them have views similar to me | 3 | 2 | ||

| Most of them have views different from me | 4 | 1 | ||

| Don’t know much about their political views | 5 | Missing | ||

| 31. If you have a difficult problem to manage, are there people outside your household you can ask for help? | No, nobody | 1 | ||

| Yes, a few | 2 | |||

| Yes, some | 3 | |||

| Yes, a lot | 4 | |||

| 32. If you had friends or co-workers whose opinions on politics differed from yours, would you have a hard time conversing with them? | Very hard | 1 | ||

| A bit hard | 2 | |||

| Not too hard | 3 | |||

| Not hard at all | 4 | |||

| Traditionalism | Please tell me how you feel about the following statements. 58. For the sake of the family, the individual should put his personal interests second. | Strongly agree Somewhat agree Somewhat disagree Strongly disagree | 1 2 3 4 | 3 2 10 |

| 59. In a group, we should sacrifice our individual interest for the sake of the groups collective interest. | ||||

| 60. For the sake of national interest, individual interest could be sacrificed. | ||||

| 61. When dealing with others, developing a long-term relationship is more important than securing one’s immediate interest. | ||||

| 62. Even if parents’ demands are unreasonable, children still should do what they ask. | ||||

| 63. When a mother-in-law and a daughter-in-law come into conflict, even if the mother-in-law is in the wrong, the husband should still persuade his wife to obey his mother. | ||||

| 64. Being a student, one should not question the authority of their teacher. | ||||

| 65. In a group, we should avoid open quarrel to preserve the harmony of the group. | ||||

| 66. Even if there is some disagreement with others, one should avoid the conflict. | ||||

| 67. A person should not insist on his own opinion if his co-workers disagree with him. | ||||

| 68. Wealth and poverty, success and failure are all determined by fate. | ||||

| 69. If one could have only one child, it is more preferable to have a boy than a girl. | ||||

| Authoritarianism | I have here other statements. For each statement, would you say you … 146. Women should not be involved in politics as much as men | Strongly agree Somewhat agree Somewhat disagree Strongly disagree | 1 2 3 4 | 3 2 10 |

| 147. The government should consult religious authorities when interpreting the laws | ||||

| 148. People with little or no education should have as much say in politics as highly educated people | ||||

| 149. Government leaders are like the head of a family; we should all follow their decisions | ||||

| 150. The government should decide whether certain ideas should be allowed to be discussed in society | ||||

| 151. Harmony of the community will be disrupted if people organize lots of groups | ||||

| 152. When judges decide important cases, they should accept the view of the executive branch | ||||

| 153. If the government is constantly checked [i.e., monitored and supervised] by the legislature, it cannot possibly accomplish great things | ||||

| 154. If we have political leaders who are morally upright, we can let them decide everything | ||||

| 155. If people have too many different ways of thinking, society will be chaotic | ||||

| Interpersonal trust | How much trust do you have in each of the following types of people? 24. Your relatives 25. Trust in your neighbors 26. Trust in other people you interact with 27. Trust in people you meet for the first time | Trust fully | 1 | 5 |

| Trust a lot | 2 | 4 | ||

| Trust somewhat | 3 | 3 | ||

| Distrust somewhat | 4 | 2 | ||

| Distrust a lot | 5 | 1 | ||

| Distrust fully | 6 | 0 | ||

| Political trust | I’m going to name a number of institutions. For each one, please tell me how much trust do you have in them? 7. Trust in the executive office (president or prime minister) 8. The courts 9. National government in the capital city 10. Political parties [not any specific party] 11. Parliament 12. Civil service 13. The military or armed force 14. The police 15. Local government 16. The election commission | Trust fully | 1 | 5 |

| Trust a lot | 2 | 4 | ||

| Trust somewhat | 3 | 3 | ||

| Distrust somewhat | 4 | 2 | ||

| Distrust a lot | 5 | 1 | ||

| Distrust fully | 6 | 0 | ||

| Political participation | Here is a list of actions that people sometimes take as citizens. For each of these, please tell me whether you have done any of these things during the past three years? 70. In the past three years, have you ever contacted elected officials or legislative representatives at any level 71. Contacted civil servants or officials 72. Contacted other influential people outside the government, such as traditional leaders/community leaders. 73. Contacted news media 74. Signed a paper petition 75. Signed an online petition 76. Used the internet including social media networks to express opinions about politics and government 77. Joined a group to actively support a cause (including online) 78. Got together with others face-to-face to try to resolve local problems 79. Attended a demonstration or protest march 80. Taken an action or done something for a political cause that put you in a risk of getting injured | I have done this more than three times | 1 | 4 |

| I have done this two or three times | 2 | 3 | ||

| I have done this once | 3 | 2 | ||

| I have not done this, but I might do it if something important happens in the future | 4 | 1 | ||

| I have not done this and I would not do it regardless of the situation | 5 | 0 | ||

| Political interest | 46. How interested would you say you are in politics? | Very interested | 1 | 3 |

| Somewhat interested | 2 | 2 | ||

| Not very interested | 3 | 1 | ||

| Not at all interested | 4 | 0 | ||

| Political news channel | 52. Which one is the most important channel for you to find information about politics and government? | Television | 1 | |

| Newspaper (print and online) | 2 | |||

| Internet and social media | 3 | |||

| Radio | 4 | |||

| Other channel (please specify) | 5 |

| 1 | Asian Barometer Survey. (https://www.asianbarometer.org/index) (accessed on 6 January 2025). |

| 2 | 2019 GDP per capita: WORLD BANK GROUP (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2019&start=1960) (accessed on 13 January 2025). |

| 3 | National Statistics, R.O.C. (Taiwan) (https://nstatdb.dgbas.gov.tw/dgbasAll/webMain.aspx?k=dgmain) (accessed on 13 January 2025). |

| 4 | 2019 World Press Freedom Index: Reporters Without Borders, RSF. (https://rsf.org/en/index) (accessed on 13 January 2025). |

References

- Abramson, P., & Inglehart, R. F. (2009). Value change in global perspective. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S.-W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäck, M., & Kestilä, E. (2009). Social capital and political trust in Finland: An individual-level assessment. Scandinavian Political Studies, 32(2), 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L. B., Vlad, T., & Nusser, N. (2007). An evaluation of press freedom indicators. International Communication Gazette, 69(1), 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, N., & Jordahl, H. (2006). Free to trust: Economic freedom and social capital. Kyklos, 59(2), 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. Cultural Theory: An Anthology, 1(81–93), 949. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, A., Ohme, J., & de Vreese, C. H. (2021). Generational gaps in media trust and its antecedents in Europe. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(3), 648–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caïs, J., Torrente, D., & Bolancé, C. (2021). The effects of economic crisis on trust: Paradoxes for social capital theory. Social Indicators Research, 153(1), 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, P. (2018). The right turn in India: Authoritarianism, populism and neoliberalisation. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 48(4), 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E., & Woo, J. (2016). The origins of political trust in east Asian democracies: Psychological, cultural, and institutional arguments. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 17(3), 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C. J., Nam, Y., & Stefanone, M. A. (2012). Exploring online news credibility: The relative influence of traditional and technological factors. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(2), 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S., Fischer, K., Chaudhuri, A., Sibley, C. G., & Atkinson, Q. D. (2020). The dual evolutionary foundations of political ideology. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(4), 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, R. (2001). Addressing the digital divide. Online Information Review, 25(5), 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, J., & Newton, K. (2005). Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: Global pattern or nordic exceptionalism? European Sociological Review, 21(4), 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zúñiga, H. G., Ardèvol-Abreu, A., Diehl, T., Patiño, M. G., & Liu, J. H. (2019). Trust in institutional actors across 22 countries. Examining political, science, and media trust around the world. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 74, 237–262. [Google Scholar]

- Dinana, H., Ali, D. A., & Taher, A. (2025). Trust pathways in digital journalism: Comparing western and national news media influence on civic engagement in Egypt. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 33, pp. 41–113). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman. (2024). 2024 edelman trust barometer. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/trust/2024/trust-barometer (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of facebook “Friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, N. (2019). Untrustworthy news and the media as “Enemy of the People?” How a populist worldview shapes recipients’ attitudes toward the media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 24(2), 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, N., Steindl, N., Obermaier, M., Prochazka, F., Arlt, D., Blöbaum, B., Dohle, M., Engelke, K. M., Hanitzsch, T., Jackob, N., Jakobs, I., Klawier, T., Post, S., Reinemann, C., Schweiger, W., & Ziegele, M. (2021). Concepts, causes and consequences of trust in news media—A literature review and framework. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(2), 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, M. S. (2002). Islam and authoritarianism. World Politics, 55(1), 4–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R., Andı, S., Badrinathan, S., Eddy, K. A., Kalogeropoulos, A., Mont’Alverne, C., Robertson, C. T., Ross Arguedas, A., Schulz, A., Toff, B., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). The link between changing news use and trust: Longitudinal analysis of 46 countries. Journal of Communication, 75(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R., & Park, S. (2017). The impact of trust in the news media on online news consumption and participation. Digital Journalism, 5(10), 1281–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flew, T. (2019). Communication, culture, and governance in Asia|The crisis of digital trust in the Asia-Pacific—Commentary (Vol. 13) [Trust, digital platforms, governance, algorithms, fake news]. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/12206/2809 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Garusi, D., Juarez Miro, C., & Hanusch, F. (2025). Understanding news media trust through the lens of phenomenological sociology. Communication Theory, 35, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Girling, J. (2006). Democracy or authoritarianism: The economy and politics of modernisation in Japan. In J. Girling (Ed.), Emotion and reason in social change: Insights from fiction (pp. 27–43). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Z. H., Seet, S., & Tandoc, E. C., Jr. (2025). The news we choose to trust: Examining long-term mainstream versus non-mainstream news consumption and trust in a liberal-authoritarian media system. Journalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., & Lei, Y. (2025). The media trust gap and its political explanations: How individual and sociopolitical factors differentiate news trust preferences in Asian societies. The International Journal of Press/Politics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanitzsch, T., Van Dalen, A., & Steindl, N. (2018). Caught in the nexus: A comparative and longitudinal analysis of public trust in the press. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23(1), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D. A. (1997). An overview of the logic and rationale of hierarchical linear models. Journal of Management, 23(6), 723–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M. (2024). Confucian culture and democratic values: An empirical comparative study in east Asia. Journal of East Asian Studies, 24(1), 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2023). Inglehart–welzel cultural map. Available online: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp?CMSID=findings (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Kahan, D. M., & Braman, D. (2006). Cultural cognition and public policy. Yale Law & Policy Review, 24, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogeropoulos, A., Suiter, J., Udris, L., & Eisenegger, M. (2019). News media trust and news consumption: Factors related to trust in news in 35 countries (Vol. 13) [Trust in news, social media, digital news consumption, Public Service Broadcaster, press freedom]. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/10141 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Keele, L. (2007). Social capital and the dynamics of trust in government. American Journal of Political Science, 51(2), 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, P. D. (2020). “The enemy of the people”: Populists and press freedom. Political Research Quarterly, 73(2), 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y. (2010). Do asian values exist? Empirical tests of the four dimensions of Asian values. Journal of East Asian Studies, 10(2), 315–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiousis, S. (2001). Public trust or mistrust? Perceptions of media credibility in the information age. Mass Communication & Society, 4(4), 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Knack, S., & Zak, P. J. (2003). Building trust: Public policy, interpersonal trust, and economic development. Supreme Court Economic Review, 10, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-T. (2010). Why they don’t trust the media: An examination of factors predicting trust. American Behavioral Scientist, 54(1), 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Pickles, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social Capital and Social Trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. (2017). Building a network theory of social capital. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T., & Bates, B. J. (2009). What’s behind public trust in news media: A comparative study of America and China. Chinese Journal of Communication, 2(3), 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D., & Yang, F. (2014). Authoritarian orientations and political trust in east Asian societies. East Asia, 31(4), 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, M. K. F. (2021). Explaining the gender gap in news access across thirty countries: Resources, gender-bias signals, and societal development. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 28(3), 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, P. (2013). Media fragmentation, party system, and democracy. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(1), 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, R. I. (2010). Money and capital in economic development. Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M. J., & Flanagin, A. J. (2007). Digital media, youth, and credibility. The MIT Press. Available online: http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/26088 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., & Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, W., & Rose, R. (2001). What are the origins of political trust?: Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies. Comparative Political Studies, 34(1), 30–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y., & Lin, C. A. (2017). The impact of online social capital on social trust and risk perception. Asian Journal of Communication, 27(6), 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mužík, M., & Šerek, J. (2023). Authoritarianism, trust in media, and tolerance among the youth: Two pathways. Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J. (2013). Mechanisms of trust: News media in democratic and authoritarian regimes. Campus Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Arguedas, A. R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Digital news report 2024. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2024 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Newton, K. (2001). Trust, social capital, civil society, and democracy. International Political Science Review, 22(2), 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E. C., & Stoycheff, E. (2013). Let the people speak: A multilevel model of supply and demand for press freedom. Communication Research, 40(5), 720–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognyanova, K. (2019). The social context of media trust: A network influence model. Journal of Communication, 69(5), 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernia, R. A. (2022). Authoritarian values and institutional trust: Theoretical considerations and evidence from the Philippines. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 7(2), 204–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, M. W., & Pye, L. W. (2009). Asian power and politics: The cultural dimensions of authority. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robison, L. J., Schmid, A. A., & Siles, M. E. (2002). Is social capital really capital? Review of Social Economy, 60(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B., & Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World Politics, 58(1), 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudson, M. (2008). Why democracies need an unlovable press. Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied psychology: An International Review, 48(1), 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T. (2001). Cultural values and political trust: A comparison of the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan. Comparative Politics, 33, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, C., & How Tan, T. (2016). The media freedom-credibility paradox. Media Asia, 43(3–4), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(1), 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, N. J., & Lee, J. K. (2013). Perceptions of cable news credibility. Mass Communication and Society, 16(1), 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, J., Tsfati, Y., Boomgaarden, H., Damstra, A., Lindgren, E., Vliegenthart, R., & Lindholm, T. (2020). News media trust and its impact on media use: Toward a framework for future research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztompka, P. (1999). Trust: A sociological theory. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsfati, Y., & Ariely, G. (2014). Individual and contextual correlates of trust in media across 44 countries. Communication Research, 41(6), 760–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deth, J. W., Castiglione, D., & Wolleb, G. (2008). Handbook of social capital. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Verboord, M., Janssen, S., Kristensen, N. N., & Marquart, F. (2023). Institutional trust and media use in times of cultural backlash: A cross-national study in nine European countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 30, 19401612231187568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L., & Stones, R. (2006). Key contemporary thinkers. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Zhu, J., & Zhang, D. (2023). The paradox of information control under authoritarianism: Explaining trust in competing messages in China. Political studies, 72(4), 1431–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P. R., Mamerow, L., & Meyer, S. B. (2014). Interpersonal trust across six asia-pacific countries: Testing and extending the ‘high trust society’ and ‘low trust society’ theory. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e95555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, C. (2011). The Asian values thesis revisited: Evidence from the world values surveys. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 12(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K., & Durrance, J. C. (2008). Social networks and social capital: Rethinking theory in community informatics. The Journal of Community Informatics, 4(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. M. J. (1970). American society: A sociological interpretation (3rd ed.). Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2023). GDP per capita (current US$). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2023&start=1960 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Xu, J. (2013). Trust in Chinese state media: The influence of education, Internet, and government. The Journal of International Communication, 19(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P., Ye, Y., & Zhang, M. (2022). Exploring the effects of traditional media, social media, and foreign media on hierarchical levels of political trust in China. Global Media and China, 7(3), 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y. (2018). Traditional values and political trust in China. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 53(3), 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Effects | |||

| COUNTRY (Intercept) | 0.322 *** | 0.190 *** | 0.180 *** |

| Residual | 0.957 | 0.882 | 0.874 |

| Fixed Effects | |||

| Intercept | −0.080 | −0.010 *** | −0.010 *** |

| GDP pc | −0.050 | −0.020 | |

| Press Freedom | −0.030 | −0.030 | |

| Political interest | 0.020 *** | 0.010 | |

| Political participation | 0.050 *** | 0.050 *** | |

| Political trust | 0.340 *** | 0.310 *** | |

| Interpersonal trust | 0.130 *** | 0.120 *** | |

| Channel_Television | 0.160 *** | 0.160 *** | |

| Channel_Newspaper | 0.070 *** | 0.070 *** | |

| Channel_Internet and social media | 0.050 * | 0.080 ** | |

| Channel_Radio | 0.030 ** | 0.030 ** | |

| Gender | 0.030 *** | 0.030 *** | |

| Education | −0.020 *** | −0.020 *** | |

| Age | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Economic capital | 0.030 *** | ||

| Social capital | −0.020 * | ||

| Traditionalism | 0.090 *** | ||

| Authoritarianism | 0.020 * | ||

| Variance Explained (R2) | |||

| Marginal R2 | 0.191 | 0.204 | |

| Conditional R2 | 0.102 | 0.227 | 0.236 |

| Variance Components | |||

| Between-group variance (τ2) | 0.083 | 0.028 | 0.025 |

| Within-group variance (σ2) | 0.731 | 0.601 | 0.585 |

| Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Effects | ||||

| COUNTRY (Intercept) | 0.202 | 0.200 | 0.181 | 0.180 |

| Residual | 0.872 | 0.872 | 0.874 | 0.874 |

| Political trust | 0.072 *** | 0.077 *** | ||

| Interpersonal trust | 0.039 ** | 0.035 * | ||

| Fixed Effects | ||||

| Intercept | −0.036 | −0.035 | −0.010 | −0.009 |

| GDP pc | −0.051 | −0.044 | −0.014 | −0.017 |

| Press Freedom | 0.048 | 0.038 | −0.009 | −0.016 |

| Political interest | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| Political participation | 0.055 *** | 0.057 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.052 *** |

| Political trust | 0.323 *** | 0.322 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.312 *** |

| Interpersonal trust | 0.115 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.120 *** | 0.120 *** |

| Channel_Television | 0.152 *** | 0.153 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.156 *** |

| Channel_Newspaper | 0.064 *** | 0.065 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.068 *** |

| Channel_Internet and social media | 0.079 ** | 0.079 ** | 0.081 *** | 0.081 *** |

| Channel_Radio | 0.028 ** | 0.029 ** | 0.031 ** | 0.030 ** |

| Gender | 0.032 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.033 *** |

| Education | −0.023 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.022 *** |

| Age | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Economic capital | 0.033 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.033 *** |

| Social capital | −0.019 ** | −0.019 ** | −0.017 ** | −0.016 ** |

| Traditionalism | 0.089 *** | 0.089 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.084 *** |

| Authoritarianism | 0.018 * | 0.018 * | 0.020 ** | 0.019 ** |

| Political trust * Economic capital | −0.000 | −0.015 * | ||

| Political trust * Social capital | 0.007 | 0.024 *** | ||

| Political trust * Traditionalism | 0.009 | |||

| Political trust * Authoritarianism | −0.022 ** | |||

| Interpersonal trust * Economic capital | −0.011 | |||

| Interpersonal trust * Social capital | 0.002 | |||

| Interpersonal trust * Traditionalism | −0.015 * | |||

| Interpersonal trust * Authoritarianism | 0.024 *** | |||

| Variance Explained (R2) | ||||

| Marginal R2 | 0.199 | 0.200 | 0.198 | 0.202 |

| Conditional R2 | 0.244 | 0.246 | 0.233 | 0.236 |

| Variance Components | ||||

| Between-group variance (τ2) | 0.051 | 0.059 | 0.032 | 0.029 |

| Within-group variance (σ2) | 0.582 | 0.583 | 0.585 | 0.584 |

| Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Effects | ||||

| COUNTRY (Intercept) | 0.182 | 0.180 | 0.164 | 0.173 |

| Residual | 0.873 | 0.874 | 0.873 | 0.873 |

| Economic capital | 0.042 *** | |||

| Social capital | 0.014 | |||

| Traditionalism | 0.062 *** | |||

| Authoritarianism | 0.049 *** | |||

| Fixed Effects | ||||

| Intercept | −0.019 | −0.005 | 0.000 | 0.005 |

| GDP pc | −0.026 | −0.018 | −0.009 | −0.007 |

| Press Freedom | −0.030 | −0.026 | −0.015 | −0.016 |

| Political interest | 0.013 | 0.013 * | 0.014 * | 0.014 * |

| Political participation | 0.050 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.055 *** | 0.059 *** |

| Political trust | 0.313 *** | 0.314 *** | 0.311 *** | 0.311 *** |

| Interpersonal trust | 0.115 *** | 0.116 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.117 *** |

| Channel_Television | 0.152 *** | 0.156 *** | 0.155 *** | 0.156 *** |

| Channel_Newspaper | 0.066 *** | 0.069 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.069 *** |

| Channel_Internet & social media | 0.079 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.082 *** | 0.083 *** |

| Channel_Radio | 0.029 ** | 0.030 ** | 0.029 ** | 0.031 ** |

| Gender | 0.032 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.032 *** |

| Education | −0.025 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.022 *** |

| Age | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Economic capital | 0.021 | 0.034 *** | 0.036 *** | 0.035 *** |

| Social capital | −0.013 * | −0.015 | −0.017 * | −0.018 ** |

| Traditionalism | 0.084 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.092 *** | 0.086 *** |

| Authoritarianism | 0.016 * | 0.018 * | 0.017 * | 0.035 * |

| GDP pc * Economic capital | −0.002 | 0.037 * | ||

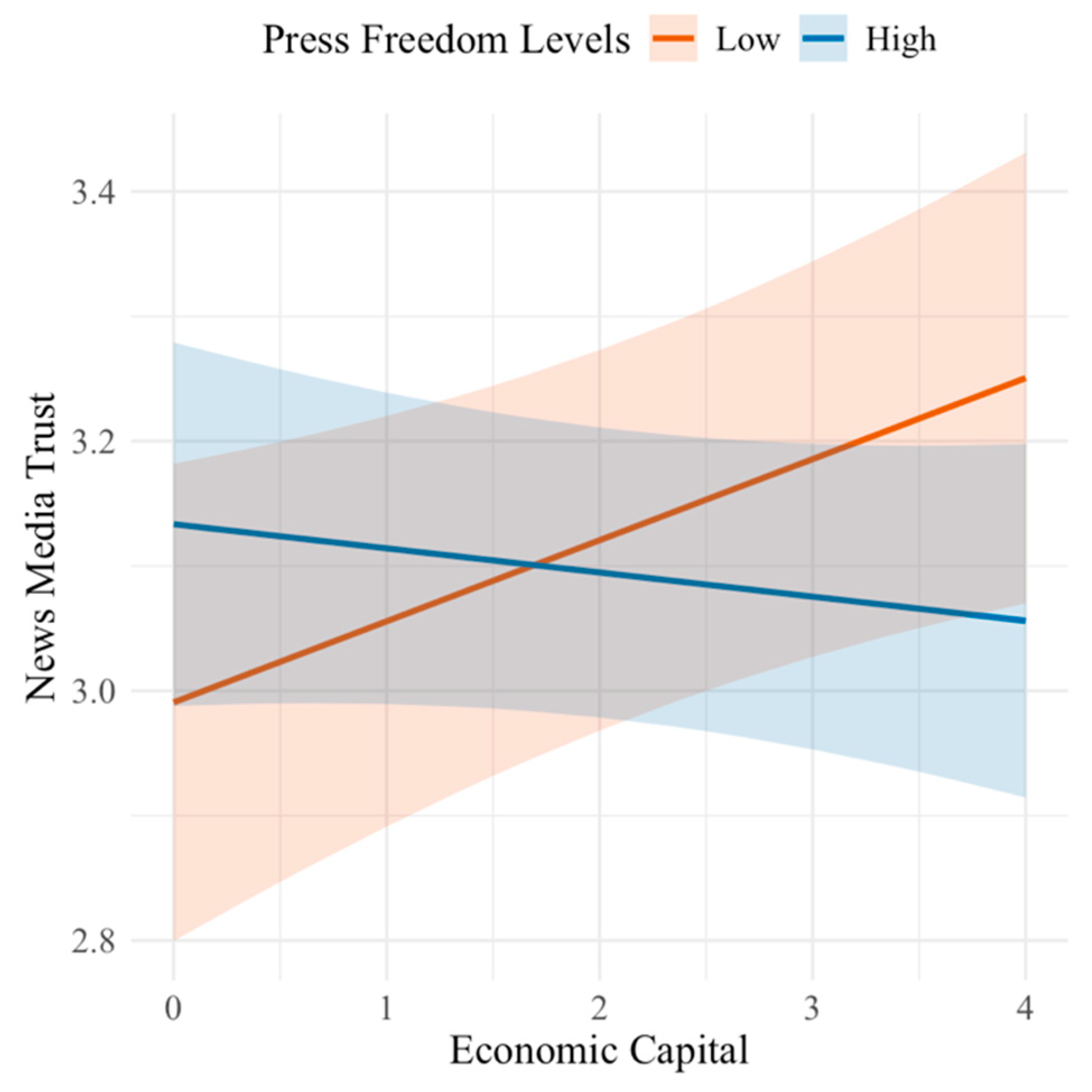

| Press Freedom * Economic capital | −0.037 * | −0.002 | ||

| GDP pc * Social capital | 0.002 | |||

| Press Freedom * Social capital | 0.003 | |||

| GDP pc * Traditionalism | 0.018 | |||

| Press Freedom * Traditionalism | 0.015 | |||

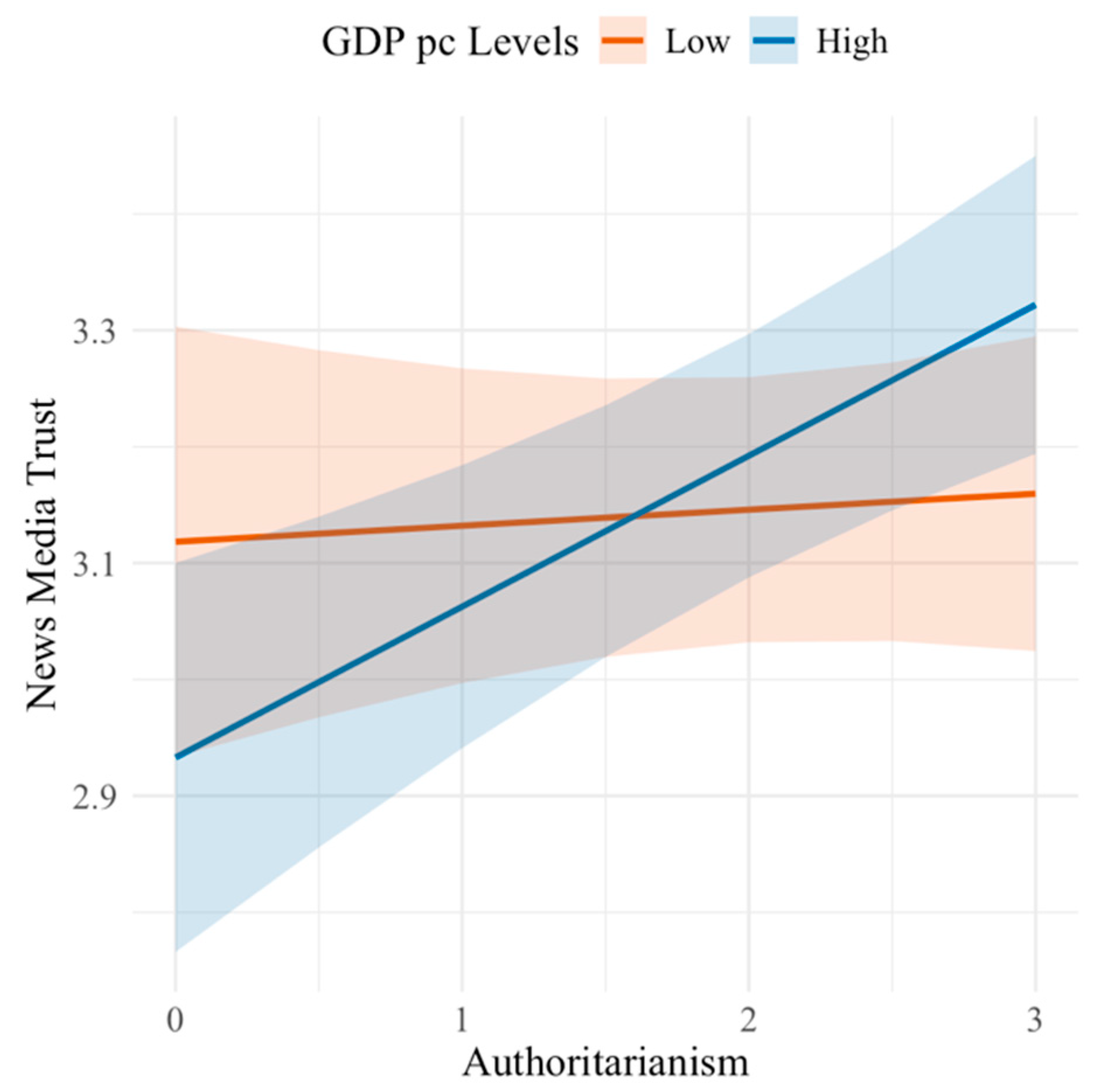

| GDP pc * Authoritarianism | 0.037 * | |||

| Press Freedom * Authoritarianism | −0.002 | |||

| Variance Explained (R2) | ||||

| Marginal R2 | 0.199 | 0.204 | 0.204 | 0.208 |

| Conditional R2 | 0.234 | 0.237 | 0.235 | 0.240 |

| Variance Components | ||||

| Between-group variance (τ2) | 0.035 | 0.025 | 0.075 | 0.052 |

| Within-group variance (σ2) | 0.583 | 0.583 | 0.584 | 0.584 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, K.; Xu, Z. Trust in News Media Across Asia: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual and Societal Factors. Journal. Media 2026, 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010008

Du K, Xu Z. Trust in News Media Across Asia: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual and Societal Factors. Journalism and Media. 2026; 7(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Ke, and Zhe Xu. 2026. "Trust in News Media Across Asia: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual and Societal Factors" Journalism and Media 7, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010008

APA StyleDu, K., & Xu, Z. (2026). Trust in News Media Across Asia: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual and Societal Factors. Journalism and Media, 7(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010008