Dark Tourism Storytelling and Trauma Narratives: Insights from Romanian Promotional (Tourism) Campaigns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dark Tourism and Thanatourism: Conceptual Foundations

2.2. Narrative Strategies and Storytelling in Tourism Communication

2.2.1. Storytelling as a Structuring Mechanism

2.2.2. Framing, Representation, and Power

2.2.3. Emotional and Symbolic Functions of Narratives

2.2.4. Storytelling as Cultural Mediation

2.3. Emotional Branding and the Ethics of Representation

2.3.1. Emotional Branding as Technology of Affect

2.3.2. Commodification, Simplification, and Ethical Tensions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

Working Hypotheses

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Analytical Procedure

3.4. Coding Framework and Analytical Categories of Romanian Dark Tourism Campaigns

3.5. Ethical Aspects

3.6. Research Credibility and Validation

4. Findings and Results

4.1. Analytical Procedure: From Coding to Cross-Case Interpretation of Campaigns

4.2. Conceptual Clustering: Narrative Convergence and Divergence

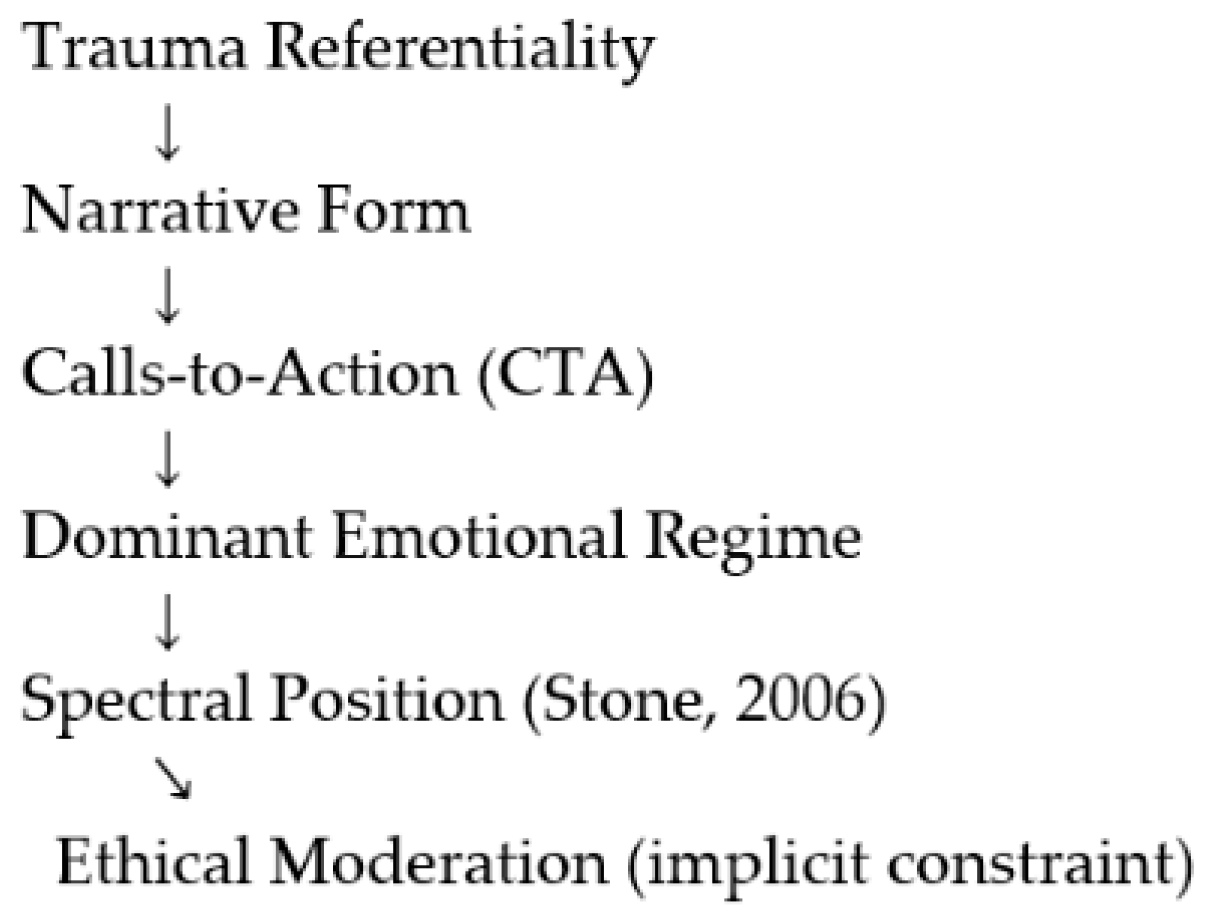

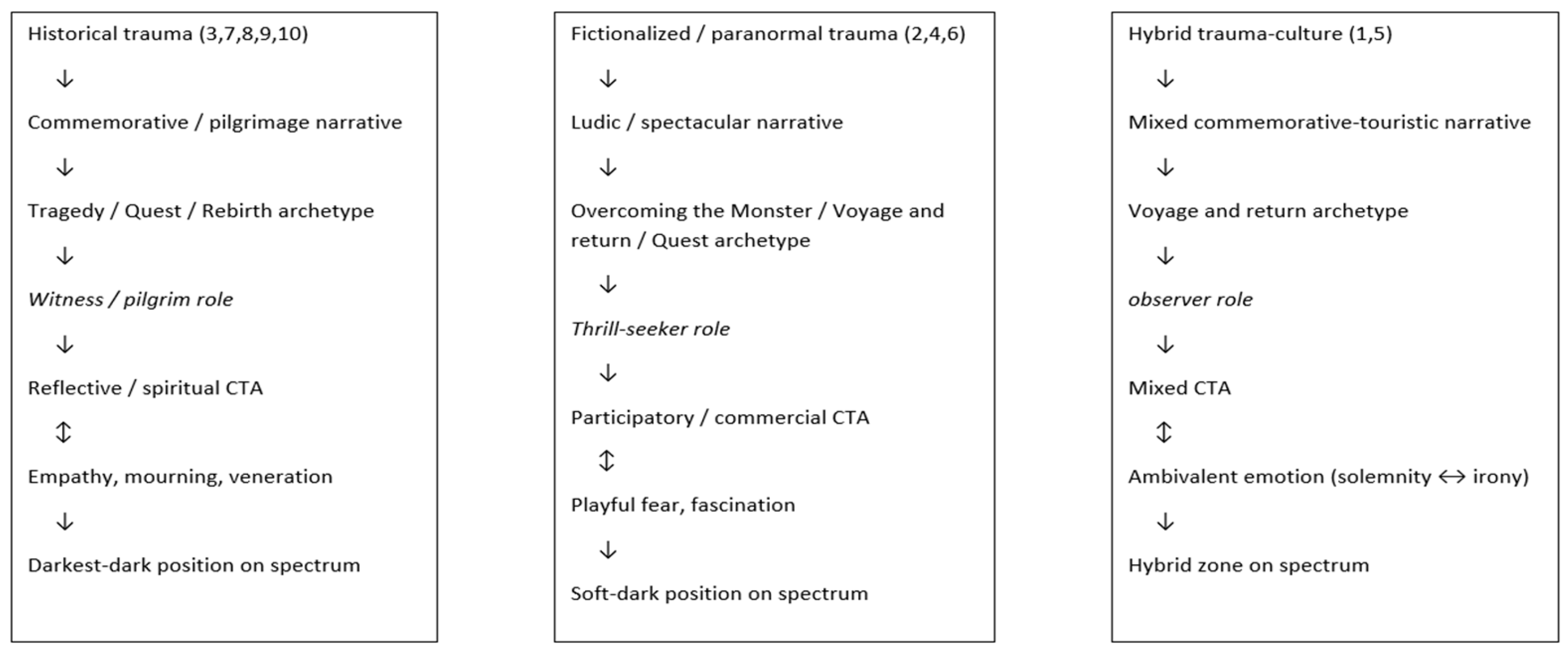

4.3. Axial Coding: Structural Relationships

4.3.1. From Traumatic Referents to Narrative Design (H1)

- P1. Authentic trauma → memorial narrative (civic or religious); fictionalized trauma → ludic/spectacular narrative; hybrid trauma → mixed narrative.

4.3.2. Narrative Archetypes/Structures as Underlying Structures (H2)

- P2: Narrative archetype → experiential positioning → CTA & emotional regime.

4.3.3. CTA as a Pragmatic Joint Between Narrative and Affect (H4)

- P3. Memorial narratives → reflective/spiritual CTAs; ludic narratives → commercial/participatory CTAs; hybrids → mixed CTAs.

4.3.4. Emotional Regimes as Outcomes of Narrative–CTA Pairing

- P4. Narrative × CTA → Emotions: civic/religious memorial + reflective/spiritual CTA → solemn affects (3, 7, 8, 9, 10); ludic + commercial/participatory CTA → playful fear/fascination (2, 6); hybrid + mixed CTA → mixed affects (1, 5).

4.3.5. Mapping to Stone’s Spectrum

- P5. Emotions → Spectral position: solemn (empathy/indignation/veneration) → darkest dark; ludic (playful fear/fascination) → soft dark; mixed → hybrid/intermediate.

4.4. Theoretical Implications

4.5. Synthesis of Findings

4.6. Interview Methodology and Interpretation

4.6.1. Analytical Framework and Method

4.6.2. Overview of Themes

- (a)

- Negotiating Memory and Market: Demand and Motivation

- (b)

- Ethical Reflexivity and the Representation of Suffering

- (c)

- Emotional Regimes and Storytelling Strategies

- (d)

- Audience Differentiation and the Politics of Reception

- (e)

- Digital Storytelling and the Mediation of Memory

4.6.3. Integrative Discussion

- Institutional discourse (Interviews 3–4) prioritizes pedagogy and commemoration, producing sober emotional regimes and codified ethical standards.

- Religious-memorial discourse (Interview 2) infuses dark heritage with spiritual transcendence, transforming suffering into sanctity.

- Commercial storytelling discourse (Interviews 1 and 5) negotiates authenticity and attraction through narrative design, transforming traumatic history into experience and experiential learning.

4.6.4. Summary Table—Thematic Synthesis

4.6.5. Concluding Remarks

4.7. Reinterpretation of Hypotheses H1–H7

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agamben, G. (1998). Homo sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A., Mirza, M., Ahmad-ur-Rehman, M., & Ilyas, S. (2023). Positive emotions, destination brand equity and word of mouth: Mediating role of satisfaction. International Journal of Business and Economic Affairs, 8(3), 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhther, N., & Tetteh, D. A. (2021). Global mediatized death and emotion: Parasocial grieving—Mourning #StephenHawking on Twitter. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying, 87(1), 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariès, P. (1981). The hour of our death. Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Atzeni, M., Chiappa, G., & Pung, J. (2021). Enhancing visit intention in heritage tourism: The role of object-based and existential authenticity in non-immersive virtual reality heritage experiences. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(2), 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M. (1997). Narratology: Introduction to the theory of narrative. University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biran, A., Poria, Y., & Oren, G. (2011). Sought experiences at dark heritage sites. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, C. (2004). The seven basic plots: Why we tell stories. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, M. S., & Pezzullo, P. C. (2010). What’s so ‘dark’ about ‘dark tourism’? Death, tours, and performance. Tourist Studies, 9(3), 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S. (2018). Qualitative interviewing. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, A. C., & Angeli, D. D. (2020). Emotions and critical thinking at a dark heritage site: Investigating visitors’ reactions to a First World War museum in Slovenia. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 16(3), 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C. N., & Santos, C. A. (2009). Interpreting slavery tourism: Articulating visitors’ emotions. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(3), 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carù, A., & Cova, B. (2006). How to facilitate immersion in a consumption experience: Appropriation operations and service elements. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 5(1), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. (2012). Tourists as story-builders: Narrative construction at a heritage museum. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(5), 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. (2011). Educational dark tourism at an in populo site: The Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. (2015). Dark tourism as/is pilgrimage. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(12), 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2017). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dostoevsky, F. (1994). Demons (R. Pevear, & L. Volokhonsky, Trans.). Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dresler, E. (2023). Multiplicity of moral emotions in educational dark tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 46, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, A. (2016). Shock tourism—Between sensation and empathy. A 9/11 case study. Folia Turistica, 39, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J. E. (2004). Narrative processing: Building consumer connections to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(1–2), 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Longman. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimon-Benea, A., & Vid, I. (2025). Narrative techniques in Romanian podcasts: A qualitative case study analysis. Journal of Media, 6(4), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W. R. (2009). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monographs, 51(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fog, K., Budtz, C., Munch, P., & Blanchette, S. (2005). Storytelling: Branding in practice. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality: Volume 1—An introduction. Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- García-Rosell, J., Sheppard, V., & Fennell, D. (2024). Editorial: Animals as dark tourism attractions: Experiences, contexts, and ethics. Frontiers in Sustainable Tourism, 3, 1502163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Gobé, M. (2009). Emotional branding: The new paradigm for connecting brands to people. Allworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimwood, B. S. R., Caton, K., & Cooke, L. (Eds.). (2018). New moral natures in tourism (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & MacQueen, K. M. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.-C. (2015). The transparency society. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ironside, R. (2023). Death, Ghosts, and Spiritual Tourism: Conceptualizing a Dark Spiritual Experience Spectrum for the Paranormal Market. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 37(4), 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2015). Sharing Tourism Experiences: The Posttrip Experience: The Posttrip Experience. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar, R., Aryal, D., & Karki, N. (2019). Dark tourism: A preliminary study of Barpak and Langtang as seismic memorial sites of Nepal. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Education, 9, 88–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2014). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Laqueur, T. W. (2015). The work of the dead: A cultural history of mortal remains. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, J. (2010). Dark tourism and sites of crime. In B. Leppänen (Ed.), Crime and media studies (Chapter 12). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, J. (2017). Dark tourism. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, J. J. (2018). Dark tourism visualisation: Some reflections on the role of photography. In P. R. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton, R. Sharpley, & L. White (Eds.), The Palgrave MacMillian handbook of dark tourism studies (pp. 585–602). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, J. J., & Foley, M. (2000). Dark tourism: The attraction of death and disaster. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, C. (2022). Touring ‘post conflict’ Belfast. Irish Journal of Sociology, 30(2), 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Zeng, S., & Tay, K. (2024). Tourism storytelling research progress and trends: A systematic literature review on sdgs. Journal of Lifestyle and SDGs Review, 5(1), e02231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D. (2017). Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage and the need for critical evaluation. Tourism Management, 61, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Linke, U. (2010). Body shock: The political aesthetics of death. Social Analysis, 54(2), 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. (1999). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. University of California Press. Available online: https://books.google.ro/books/about/The_Tourist.html?id=6V_MQzy021QC (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Marinis, V. (2016). Death and the afterlife in Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, A., & Buda, D. (2018). Dark tourism and affect: Framing places of death and disaster. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(6), 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2018). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K. (2017). The content analysis guidebook. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podoshen, J. S. (2013). Dark tourism motivations: Simulation, emotional contagion and topographic comparison. Tourism Management, 35, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y., Butler, R., & Airey, D. (2010). Tourism, religion and religiosity: A holy mess. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(4), 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, T. J. (2012). ‘Dark tourism’ and the ‘kitschification’ of 9/11. Tourist Studies, 12(3), 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodan, I. (2021). Indonesia—A goldmine of dark tourism destinations. The Annals of the University of Oradea Economic Sciences, 30(1), 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Propp, V. (1968). Morphology of the folktale (2nd ed.). University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, Y., Björk, P., & Weidenfeld, A. (2016). Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tourism Management, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raušl, K., Prevolšek, B., & Rangus, M. (2022). Inclusion of dark heritage in the contemporary tourist offer of the city of Maribor. Univerza v Mariboru, Univerzitetna Založba. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renanda, J. (2020). Destination branding through semiotics analysis of Wonderful Indonesia 2018: “The more you feel, the more you know”. K Ta Kita, 8(1), 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G., & van der Ark, L. A. (2013). Dimensions of cultural consumption among tourists: Multiple correspondence analysis. Tourism Management, 37, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rojek, C. (1993). Ways of escape: Modern transformations in leisure and travel. Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N. B. (2012a). Community-based cultural tourism: Issues, threats and opportunities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(1), 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N. B. (2012b). Tourism imaginaries: A conceptual approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A., Anghel-Vlad, S., Negruț, L., & Goje, G. (2021). Tourists’ motivations for visiting dark tourism sites: Case of Romania. Annals of Faculty of Economics, 1(1), 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, A. V. (1996). Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, A. V. (2018). Thanatourism and its discontents: An appraisal of a decade’s work with some future issues and directions. Tourism Management, 64, 292–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. R. (2009). The darker side of travel: The theory and practice of dark tourism. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, D. (1987). Commentary: Updating the sublime. Studies in Romanticism, 26(2), 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the pain of others. Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Stepchenkova, S., & Belyaeva, V. (2021). The effect of authenticity orientation on existential authenticity and postvisitation intended behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 60(2), 401–416, (Original work published 2020). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steriopoulos, E., Khoo-Lattimore, C., Wong, H. Y., Hall, J., & Steel, M. (2023). Heritage tourism brand experiences: The influence of emotions and emotional engagement. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 30(3), 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P. R. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 54(2), 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P. R. (2012). Dark tourism and significant ‘other’ death: Towards a model of mortality mediation. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1565–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P. R. (2013). Dark tourism scholarship: A critical review. International Journal of Culture, Tourism, and Hospitality Research, 7(3), 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P. R., & Grebenar, A. (2021). ‘Making tragic places’: Dark tourism, kitsch and the commodification of atrocity. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 20(4), 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P. R., & Sharpley, R. (2008). Consuming dark tourism: A thanatological perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 574–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlow, P. E. (2005). Dark tourism: The appealing ‘dark’ side of tourism and more. In M. Novelli (Ed.), Niche tourism (pp. 47–57). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Park, C. W. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wailmi, K., Mahmudin, T., Novedliani, R., & Samaduri, L. (2024). Dark tourism as a tourism and culture development strategy in Indonesia. Reslaj Religion Education Social Laa Roiba Journal, 6(3), 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, T. (1991). Modern Death: Taboo or not Taboo? Sociology, 25(2), 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, C. (2006). Philosophical and methodological praxes in dark tourism: Controversy, contention and the evolving paradigm. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 12(2), 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, C. (2020). Visitor perceptions of European Holocaust heritage: A social media analysis. Tourism Management, 81, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D. W. M., & Salah, M. B. (2024). Methods and value of storytelling for stakeholders in post-disaster tourism scenarios. Foresight, 26(3), 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Shen, C., Wang, E., Hou, Y., & Yang, J. (2019). Impact of the perceived authenticity of heritage sites on subjective well-being: A study of the mediating role of place attachment and satisfaction. Sustainability, 11(21), 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X., Fu, X., Lin, V. S., & Xiao, H. (2022). Integrating authenticity, well-being, and memorability in heritage tourism: A two-site investigation. Journal of Travel Research, 61(2), 378–393, (Original work published 2021). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G., Chen, W., & Wu, Y. (2022). Research on the effect of authenticity on revisit intention in heritage tourism. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 883380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analytical Category | Coding Dimensions (Operaționalizate) | Theoretical Grounding |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative structure | Archetypal plot (Booker’s seven plots); narrative pattern (linear, cyclical, fragmented); moral positioning; resolution/closure | Booker (2004); Bruner (1991); Fisher (2009) |

| Narrative type | Emotional/Historical/Ironic/Symbolic/Ludic | Escalas (2004); Salazar (2012b); Bruner (1991) |

| Dominant emotions | Fear/Nostalgia/Compassion/Revolt (coded based on textual and visual emotional tone indicators: imagery, language, color palette, soundtrack cues) | Gobé (2009); Thomson et al. (2005); Podoshen (2013); Han (2015) |

| Call-to-action (CTA) | Visit/Reflect/Social engagement (coded from explicit imperative language, hashtags, hyperlinks, slogans, or implied invitations to action) | Salazar (2012a, 2012b); Han (2015); Atzeni et al. (2021) |

| Narrative & visual techniques | 1. Symbolism (presence of culturally charged or commemorative symbols); 2. Image-text ratio (text-dominant/image-dominant/balanced); 3. Montage and sequencing (chronological vs. associative editing); 4. Framing strategies (close-up, wide shot, aerial, immersive POV); 5. Use of contrast and color grading (dark, desaturated, vivid); 6. Narrative voice (first-person, institutional, impersonal) | Entman (1993); Fairclough (1995); Hall (1997); Fog et al. (2005); García-Rosell et al. (2024) |

| Interview Block | Analytical Focus | Example Guiding Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Professional role | Institutional position and involvement in dark tourism communication | “What is your role in promoting or curating sites related to trauma or memory?” |

| Narrative design | Storytelling strategies and narrative choices | “How are narratives structured when communicating traumatic histories?” |

| Emotional framing | Emotional tone and affective strategies | “Which emotions are intentionally elicited in audiences?” |

| Ethical moderation | Ethical limits and representational responsibility | “Where do you draw ethical boundaries in representing suffering?” |

| Audience reception | Target publics and audience differentiation | “Do domestic and international audiences respond differently?” |

| Digital mediation | Use of digital storytelling and future directions | “How do digital tools shape the communication of dark heritage?” |

| No. | Campaign | Organizer | Period | Narrative Structure (Booker) | Narrative Type | Narrative Type (Bruner) | Dominant Emotions | CTA Type | Narrative & Visual Techniques | Critical Observations | Analytical Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chernobyl Tour | Iri Travel | 2020–2025 | Voyage and Return | Post-disaster tourism | Historical-documentary | controlled fear, curiosity, awe | commercial, exploratory | hybrid documentary visuals, mediated memory | trauma aestheticization through safe framing | Dark exhibitions, controlled commodification |

| 2 | Halloween with Dracula | Transylvania Live | 2020–2025 | Overcoming the Monster & Quest | Fictional horror tourism | Mythical-playful | playful fear, thrill, euphoria | immersive, participatory | gothic trope usage, performative rituals | fictionalization of death, entertainment focus | Soft dark tourism—entertainment |

| 3 | The Last Day of Ceaușescu | Red Patrol | 2020–2025 | Tragedy & Rebirth | Political trauma re-enactment | Historical-dramatic | tension, empathy, civic reflection | educational, participatory | chronological re-enactment, historic spaces | blurred lines between memory and spectacle | Hard dark tourism—memorial |

| 4 | Guided Tour Bellu Cemetery | Asociația Coolturală | 2021–2025 | Voyage and Return | Urban death heritage | Experiential-sensory | curiosity, nostalgia, mild fear | experiential, cultural | atmospheric framing, funerary symbolism | aestheticization of death, soft memorial tone | Soft dark urban tourism |

| 5 | Maramureș Tour—Sighet & Săpânța | Europa Turism | 2022–2025 | Voyage and Return | Cultural-memorial hybrid | Narrative mosaic | solemnity, nostalgia, humor | cultural-reflective | contrast traumatic vs. ludic visuals | balanced memorialization and tourism | Cultural-memorial hybrid |

| 6 | Hoia-Baciu Project | Hoia-Baciu Project | 2020–2025 | Voyage and Return + Mystery | Paranormal & folklore | Sensory-imaginative | fear, intrigue, excitement | commercial, experiential | nocturnal framing, legend narration | paranormal commodification | Soft dark tourism—entertainment |

| 7 | 1989 Revolution Tour (Timișoara) | Memorial of the Revolution | 2020–2025 | Rebirth & Overcoming the Monster | Political memory walk | Civic-memorial | hope, empathy, solemnity | civic-reflective | archival memory + site visiting | moral and civic educational purpose, remembrance duty | Hard dark tourism—memorial |

| 8 | “Saints of the Prisons” Tour | Orthodoxia Tinerilor | 2021–2025 | Quest + Rebirth | Religious martyrdom tour | Spiritual-testimonal | veneration, sorrow, reverence | Spiritual reflective, ritual | hagiographic framing, sites of suffering | sacralization of trauma, pilgrimage tone | Dark pilgrimage/hard dark memorial |

| 9 | Virtual Tours—Sighet Memorial | Memorial Sighet | 2020–2025 | Quest & Rebirth | Digital memorial heritage | Documentary-educational | empathy, indignation, solemnity | Civic reflective, educational | archival images, immersive virtual museum | virtual mediation of trauma | Digital dark tourism—memorial |

| 10 | Jewish Heritage Tour—Iași | Rolandia/Momentum Tours | 2020–2025 | Quest & Tragedy | Holocaust memorial walk | Testimonial-historical | sorrow, empathy, moral outrage | civic-reflective | memorial plaques, historical chronotope | high moral stakes, remembrance duty | Darkest dark tourism—Holocaust memorial |

| Cluster | Defining Narrative Characteristics | Identified Campaigns | Key Features | Stone (2006) Correspondence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | memorial/historical | 3, 7, 9, 10 | Elevated solemnity, reflective/civic CTA, civic and moral emotions, authentic memorialization | Dark Conflict Sites/Dark Shrines, Darkest dark (Camps of Genocide + Shrine) |

| Cluster 2 | paranormal/fictionalized | 2, 4, 6 | High fictionalization, commercial/participatory CTA, playful emotions, spectacularization | Entertainment-oriented dark tourism |

| Cluster 3 | Cultural hybrid, tragic-playful | 1, 5 | Contrast between solemnity and commercial touristic elements, cultural/participatory CTA, mixed emotions | Hybrid memorial—soft dark tourism |

| Cluster 4 | Religious-memorial (pilgrimage) | 8 | Pilgrimage structure, spiritual CTA, veneration, sacred dolorism | Darkest dark (Camps of Genocide + Shrine), Dark pilgrimage/shrines |

| Narrative Archetype (Booker) | Experience Framing | CTA Typology | Emotional Regime | Spectral Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quest, Rebirth | Participant/Pilgrim | Reflective/Spiritual/commemorative | Empathy, devotion, dolorism | Darkest dark |

| Quest, Tragedy | Solemn witness | Memorial/Reflective/commemorative | Mourning, empathy, indignation | Darkest dark |

| Overcoming the Monster, Comedy | Thrill-seeker | Commercial/Participatory | Playful fear, fascination | Soft dark |

| Comedy/Rebirth | Observer | Cultural/Mixed | Irony, ambivalence | Hybrid/Intermediate |

| Theme | Illustrative Excerpt (Condensed) | Interpretive Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Demand & Motivation | “For Romanians, that period is still an open wound.” (Int. 5) | Memory proximity shapes participation; foreign curiosity vs. local hesitation. |

| Ethical Reflexivity | “We don’t dramatize, but we must be responsible.” (Int. 1) | Ethics as communicative moderation; avoidance of spectacle. |

| Emotional Strategy | “It’s like a play—fear, despair, irony, tragedy.” (Int. 5) | Storytelling as affective choreography; curated empathy. |

| Audience Difference | “Romanians are emotional, foreigners analytical.” (Int. 3) | Divergent affective regimes: national vs. global reception. |

| Digital Mediation | “Virtual tours help, but the visit is irreplaceable.” (Int. 2) | Digital storytelling is an educational extension, not a substitution. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barbu Kleitsch, O.; Bader-Jurj, S. Dark Tourism Storytelling and Trauma Narratives: Insights from Romanian Promotional (Tourism) Campaigns. Journal. Media 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010006

Barbu Kleitsch O, Bader-Jurj S. Dark Tourism Storytelling and Trauma Narratives: Insights from Romanian Promotional (Tourism) Campaigns. Journalism and Media. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbu Kleitsch, Oana, and Simona Bader-Jurj. 2026. "Dark Tourism Storytelling and Trauma Narratives: Insights from Romanian Promotional (Tourism) Campaigns" Journalism and Media 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010006

APA StyleBarbu Kleitsch, O., & Bader-Jurj, S. (2026). Dark Tourism Storytelling and Trauma Narratives: Insights from Romanian Promotional (Tourism) Campaigns. Journalism and Media, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010006