Media and Women Politicians in Southern Africa: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

- How do the media in Southern Africa portray women politicians?

- ii.

- What reporting practices reinforce or challenge gendered frames, such as the “political glass cliff”?

2. Theoretical Underpinnings: The Feminist Media Theory

Global Perspectives on Media Framing of Women Politicians

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Approach

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

3.3. Information Sources

3.4. Search Strategy

3.5. Selection Process

3.6. Data Extraction

3.7. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.8. Data Synthesis

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Studies

4.2. Results of Individual Studies

4.2.1. Publication Trends (2000–2025)

4.2.2. Geographic Distribution of Studies

4.2.3. Types of Publications

4.2.4. Research Designs & Methods in Reviewed Studies

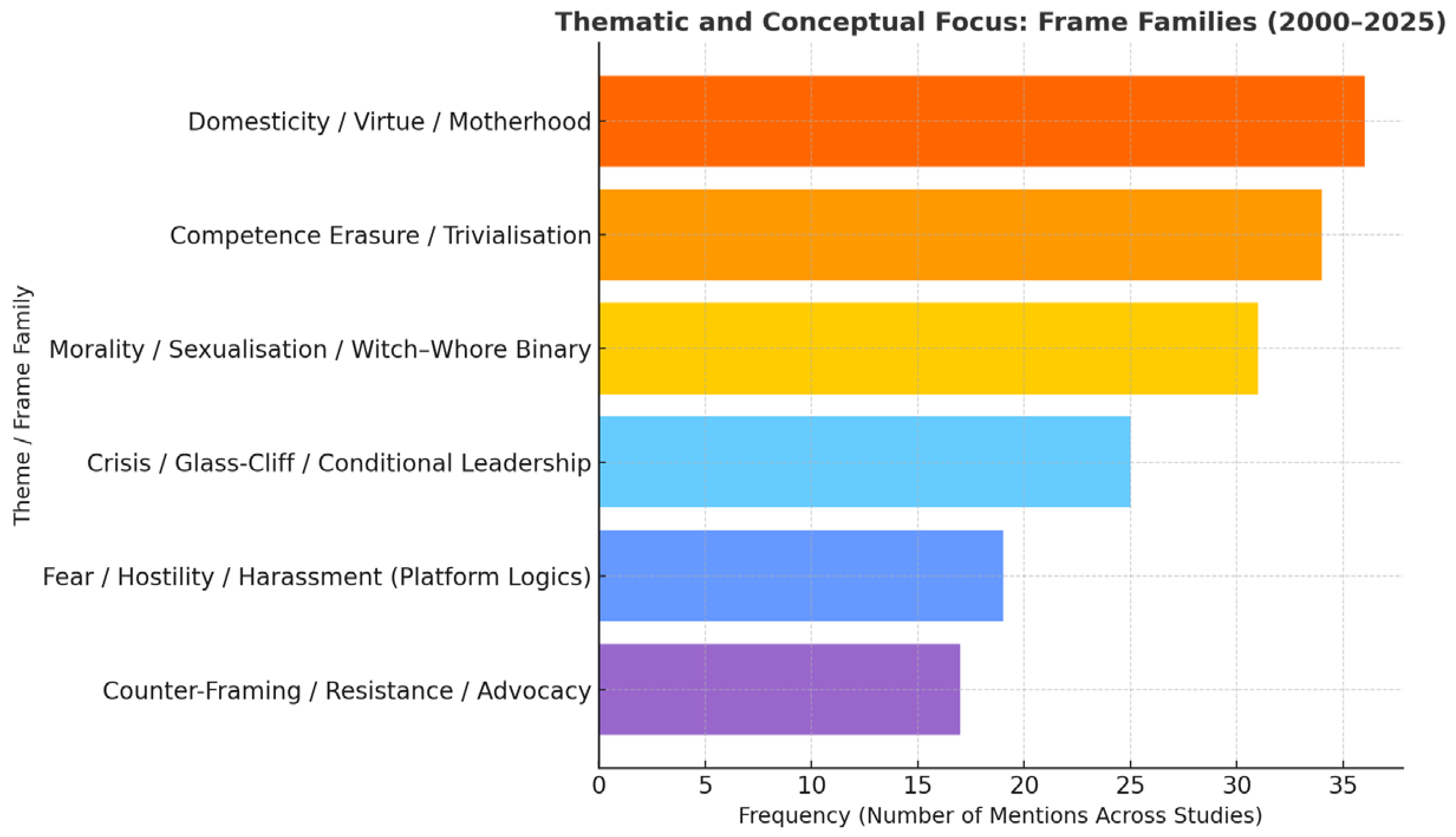

4.2.5. Thematic/Conceptual Focus (Frame Families; Multi-Coding)

4.2.6. Theoretical or Conceptual Frameworks Used

4.2.7. Journals/Sources of Publication (Top Outlets by Frequency)

4.2.8. Population/Unit of Analysis

4.2.9. Data Collection Techniques (Primary)

4.2.10. Funding & Institutional Affiliations (Reported)

4.3. National Media Contexts and Variations in Gendered Framing

4.4. Qualitative Thematic Analysis of the Review Literature

4.4.1. Cultural–Patriarchal Archetypes (Mother/Whore/Witch)

4.4.2. Competence Erasure and Conditional Leadership (“Political Glass Cliff”)

4.4.3. Fear Production and Symbolic Violence

4.4.4. Reinforcing Practices: Gendered Sourcing, Visibility and Lexical/Visual Bias

4.4.5. Structural Legitimation of Bias: Party, Religious and Cultural Gatekeeping

4.4.6. Counter-Practices: Gender-Sensitive Journalism and Feminist Resistance

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Theory and Practice

5.2. Reporting Biases

5.3. Certainty of Evidence

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adcock, C. (2010). The politician, the wife, the citizen, and her newspaper: Rethinking women, democracy, and media (ted) representation. Feminist Media Studies, 10(2), 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanu, B., Asafo, S., & Quashigah, T. (2023). Framing competence: African women leaders’ representation in US news media. Journal of Communications, Media and Society (JOCMAS), 9(1), 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2018). Empowered: Popular feminism and popular misogyny. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiten, D. (2009). Gender transformation and media representations: Journalistic discourses in three South African newspapers [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pretoria]. [Google Scholar]

- Chandilanga, H. C., & Chikaipa, V. (2024). ‘No flowers for the new boss’: Interrogating malawian newspapers political cartoon stereotypical representations of a woman anti-corruption bureau director. Agenda, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikafa-Chipiro, R. (2020). African feminist activism and democracy: Social media publics and Zimbabwean women in politics online. African Journal of Inclusive Societies, 3, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikaipa, V. (2019). Caring mother or weak politician? A semiotic analysis of editorial cartoon representations of president joyce banda in Malawian newspapers. Critical Arts, 33(2), 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimba, M. D. (2006). Women, media and democracy: News coverage of women in the Zambian press. The University of Wales College of Cardiff. [Google Scholar]

- Chirongoma, S., & Mavengano, E. (2023). Introduction: The nexus between gender, religion and the media in Zimbabwean electoral politics. In Electoral politics in zimbabwe, Vol II: The 2023 election and beyond (pp. 1–16). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Chiwanda, M. G. (2006). Mass media coverage of election campaigns and its influence on the voter: Study of the 2004 Malawi general elections [Master’s thesis, Tangaza University College]. Tangaza University Digital Repository. Available online: https://repository.tangaza.ac.ke/server/api/core/bitstreams/be4f2f90-d612-49c1-9c13-1eb94607cc0d/content (accessed on 10 November 2025). Tangaza University Digital Repository.

- Coffie, A., & Medie, P. A. (2021). Media representation of women parliamentary candidates in Africa: A study of the daily graphic newspaper and Ghana’s 2016 election. In L. R. Arriola, M. C. Johnson, & M. L. Phillips (Eds.), Women and power in Africa: Aspiring, campaigning, and governing. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, B. M. (2021). The representation of the female politician in online news media outlets: Nkosazana dlamini-zuma and theresa may. University of Johannesburg. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, T. (2013). Engendering politics and parliamentary representation in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 2(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ette, M. (2017). Where are the women? Evaluating visibility of Nigerian female politicians in news media space. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(10), 1480–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauti, C. (2022). African women in politics: An analysis on the challenges faced by women in politics in Zimbabwe [Master’s thesis, OsloMet-Storbyuniversitetet]. [Google Scholar]

- Geertsema, M. (2008). Women making news: Gender and media in South Africa. Global Media Journal, 7(12), 1. Available online: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers/4/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Geisler, G. (1995). Troubled sisterhood: Women and politics in Southern Africa: Case studies from Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana. African Affairs, 94(377), 545–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gender Links. (2015). Annual Report 2015. Available online: https://www.genderlinks.org.za/annual-reports/annual-report-2015 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gender Links. (2019). Gender audit of the May 2019 South African elections—Beyond numbers [Audit/monitoring report]. Available online: https://www.genderlinks.org.za/uploads/files/GENDER-IN-2019-SA-ELECTIONS-LR.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gender Links. (2024). SADC gender protocol barometer 2024. Gender Links for Equality and Justice. Available online: https://www.genderlinks.org.za/marang/knowledge-hub/publications/sadc-gender-protocol-barometer-2024 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gender Links (with MISA/GEMSA). (2020). Gender and media progress study (GMPS)—Regional overview [Regional research programme]. Available online: https://www.genderlinks.org.za/what-we-do/gender-and-the-media/gender-and-the-media-research (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gill, R. (2007). Gender and the media. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, R. (2016). Post-postfeminism?: New feminist visibilities in postfeminist times. Feminist Media Studies, 16(4), 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D. (2007). Weight of evidence: A framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education, 22(2), 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunde, A. (2015). Online news media, religious identity and their influence on gendered politics: Observations from malawi’s 2014 elections. The Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture, 4, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsson, A., & Wängnerud, L. (2019). The effect of media sexism on women’s political ambition: Evidence from a worldwide study. Feminist Media Studies, 19(4), 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harp, D., Loke, J., & Bachmann, I. (Eds.). (2018a). Feminist approaches to media theory and research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Harp, D., Loke, J., & Bachmann, I. (2018b). Intersectionality and visibility in news media: Representing diverse voices. Journalism Studies, 19(2), 260–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ireri, K., & Ochieng, J. (2024). Determinants of women legislators’ media coverage in a male-dominated Kenya political landscape. Journalism, 26(9), 1982–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D., Hailu, M., & Reising, L. (2019). Violators, virtuous, or victims? How global newspapers represent the female member of parliament. Feminist Media Studies, 20(5), 692–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjere, M. M. (2019). Female politicians in South Africa-image and gender discourse. African Journal of Public Affairs, 11(1), 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kasadha, J., & Kantono, R. (2021). Media representation and its impact on female candidates’ electability in parliamentary elections: A content analysis of three Ugandan newspapers. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katembo, T. K. (2005). The representation of South African women politicians in the Sunday times during the 2004 presidential and general elections [Ph.D. dissertation, Rhodes University]. [Google Scholar]

- Katongo, C. N. (2017). Female political representation in Zambia: A study of four political parties’ policies and perspectives on party gender quotas and reserved seats adoption [Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Zambia]. [Google Scholar]

- Kayuni, H. M. (2016). Women, media and culture in democratic Malawi. In Political transition and inclusive development in Malawi (pp. 169–187). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D. (2009). Gendered spectacle: New terrains of struggle in South Africa. In A. Schlyter (Ed.), Body politics and women citizens: African experiences (p. 127). Sida. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losh, E. (2014). Digital feminist activism: Girls and women transform cyberspace. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe Morna, C. (2009, April 30). South Africa: Election coverage through a gender lens. Pambazuka News. Available online: https://www.pambazuka.org/south-africa-election-coverage-through-gender-lens (accessed on 9 January 2026).

- Lubinda, C. (2021). Interest groups and the promotion of women participation in Zambia’s political processes: Case of Zambia national women’s lobby (1991–2018) [Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Zambia]. [Google Scholar]

- Luka, L., & Ugondo, P. (2025). Gendered framing in political campaign coverage: A content analysis of selected Nigerian newspapers. International Journal of Humanities, Education, and Social Sciences, 3(3), 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumby, C. (1994a). Feminism & the media: The biggest fantasy of all. Media Information Australia, 72(1), 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lumby, C. (1994b). The fantasy of feminism in the media. Feminist Review, 47, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist, M. (2024). Empowering Malawi’s girls: Media as a tool for developing equal rights and social standing [Unpublished Master’s thesis, Södertörn University]. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1964635/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2026).

- Makhunga, L. D. (2014). South African parliament and blurred lines: The ANC Women’s League and the African national congress’ gendered political narrative. Agenda, 28(2), 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangena, T. (2022). Narratives of women in politics in Zimbabwe’s recent past: The case of Joice Mujuru and Grace Mugabe. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines, 56(2), 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannya, M. M. (2013). Representation of black, young, women politicians in South African online news media: A case study of lindiwe mazibuko [Ph.D. dissertation, Stellenbosch University]. [Google Scholar]

- Manyeruke, C. (2018). A reflection on the women in Zimbabwean politics through gender lenses. Journal of African Foreign Affairs, 5(3), 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphosa, M., Tshuma, N., & Maviza, G. (2015). Participation of women in Zimbabwean politics and the mirage of gender equity. Ubuntu: Journal of Conflict and Social Transformation, 4(2), 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Mateveke, P., & Chikafa-Chipiro, R. (2020). Misogyny, social media and electoral democracy in Zimbabwe’s 2018 elections. In Social media and elections in Africa, Volume 2: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 9–29). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Matsilele, T., & Nkoala, S. (2023). Metavoicing, trust-building mechanisms and partisan messaging: A study of social media usage by selected South African female politicians. Information, Communication & Society, 26(13), 2575–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, H., & Cuklanz, L. (2014a). Feminist media research. In S. N. Hesse-Biber (Ed.), Feminist research practice: A primer (2nd ed., pp. 264–295). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, P., & Cuklanz, L. (2014b). Feminism beyond media texts: Power structures and discourses. Feminist Media Studies, 14(1), 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, L. (1993). Feminism, the public sphere, media and democracy. Media, Culture & Society, 15(4), 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRobbie, A. (2009). The aftermath of feminism: Gender, culture and social change. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2018). 15 years of reporting South African elections: Same same but different [Retrospective report]. Available online: https://mediamonitoringafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/15-years-of-reporting-South-African-elections_-Same-same-but-different-.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2019). Analysing South Africa’s media coverage of 2019 elections [Election monitoring report]. Available online: https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019electionsFinal_v2.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2022). LGE21 elections report [Election monitoring report]. Available online: https://mediamonitoringafrica.org/wordpress22/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/LGE21-Elections-Report-.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2024a). Brief 1: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections [Monitoring brief]. Available online: https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Brief-1-An-analysis-of-medias-coverage-of-the-2024-South-African-elections.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2024b). Brief 3: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections [Monitoring brief]. Available online: https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Brief-3-An-analysis-of-medias-coverage-of-the-2024-South-African-elections.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2024c). Brief 5: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections [Monitoring brief]. Available online: https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Brief-5-An-analysis-of-medias-coverage-of-the-2024-South-African-elections.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2024d). Brief 7: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections [Monitoring brief]. Available online: https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Brief-7-An-analysis-of-medias-coverage-of-the-2024-South-African-elections.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2024e). Media performance review 2024 (Interim report). Media Monitoring Africa. Available online: https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Media Monitoring Africa. (2024f, May). Media performance review: Interim report [Interim review]. Available online: https://www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/MPR_InterimReport_310524_V2.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Mhiripiri, N. A., & Ureke, O. (2018). Theoretical paradoxes of representation and the problems of media representations of Zimbabwe in crisis. Critical Arts, 32(5–6), 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MISA (SADC). (2012). Guidelines on media coverage of elections in the SADC region [Normative guideline]. Available online: https://sanef.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MISA-Guidelines-on-Media-Coverage-of-Elections-in-the-SADC-Region-2012.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Mlotshwa, K. (2018). “Invisibility and hypervisibility” of ‘Ndebele women’ in Zimbabwe’s media. Agenda, 32(3), 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu, J. (2017). Media representation of women in politics and media in southern Africa. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies, 2(7), 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu, S. (2016). Blogging, feminism and the politics of participation: The case of Her Zimbabwe. In Digital activism in the social media era: Critical reflections on emerging trends in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 271–294). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mtero, S., Parichi, M., & Madsen, D. H. (2023). Patriarchal politics, online violence and silenced voices: The decline of women in politics in Zimbabwe. Nordic Africa Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Muringa, T. P., & Adjin-Tettey, T. D. (2025). “Meaning in the service of power”: A marxist analysis of media discourse on presidential elections in South Africa. African Journalism Studies, 2(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringa, T. P., & McCracken, D. (2021). Independent online and news24 framing of Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma: A case study of the African national congress 54th national conference. Communicatio, 47, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringa, T. P., & Ndlovu, J. (2026). Examining the gendered narratives in news coverage of Joyce Banda. Social Sciences, 15(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringa, T. P., Sanele, G. J., & Aiseng, K. (2024). “We are not ready for a ‘she’ president”: Navigating media framing of women presidential hopefuls. Agenda, 1(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutizwa, A., Munhape, J., Munemo, S., & Marenga, D. L. (2024). The Zimbabwe political space: An analysis of the barriers to women’s participation in electoral processes? Africa’s Quest for Inclusion: Trends and Patterns, 4(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mutsvairo, B., & Ragnedda, M. (2017). Emerging political narratives on Malawian digital spaces. Communicatio, 43(2), 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, G. (2020). Eternal mothers, whores or witches: The oddities of being a woman in politics in Zimbabwe. Agenda, 34(4), 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, G., & Yemurai, G. (2020). Discrimination against female politicians on social media: An analysis of tweets in the run-up to the July 2018 Harmonised Elections in Zimbabwe. In Social media and elections in Africa, Volume 2: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 59–76). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu, J. (2025). Gendered political violence and the church in Africa: Perspectives from church leaders. Religions, 16(9), 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, J., & Mandiyanike, M. (2025). Gender-based violence ‘matters’: An analysis of conflicting frames of violence in South African Media. Social Sciences, 14(12), 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoshi, H. T., & Mutekwa, A. (2013). The female body and voice in audiovisual political propaganda jingles: The mbare chimurenga choir women in Zimbabwe’s contested political terrain. Critical Arts, 27(2), 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomo, S. (2016). Media representation of political leadership and governance in South Africa–press coverage of Jacob Zuma [Ph.D. dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand]. [Google Scholar]

- Nunuhe, F. M. (2020). Deconstruction off gender stereotypes in the media: An analysis of media framing of women in leadership positions in parliament and state-owned enterprises (SOE’S) in Namibia [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Namibia]. [Google Scholar]

- Olaitan, Z. M. (2024). Women’s political representation in South Africa and Botswana. In Women’s representation in African politics: Beyond numbers (pp. 123–141). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Appiah, S. (2019). Media representations of women politicians: The cases of Ghana and Nigeria [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Leeds]. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parichi, M. (2016). The representation of female politicians in Zimbabwean print media: 2000–2008. University of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Phiri, S. (2020). Political communication among female candidates and women electorates in Zambia. In Women’s political communication in Africa: Issues and perspectives (pp. 77–97). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar, K., & Bekker, I. (2007). The body as a site of struggle: Oppositional discourses of the disciplined female body. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 25(4), 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, A. L. (2011). Feminism and media in the post-feminist era: What to make of the “feminist” in feminist media studies. Feminist Media Studies, 11(1), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapitse, S., Bhila, T., & Mukurunge, T. (2019). Exploring print media coverage of female politicians in Lesotho. International Journal of All Research Writings, 2(2), 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rhode, D. L. (1995). Media images, feminist issues. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 20(3), 685–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, A., Rohrbach, T., & Krakovsky, C. (2022). “I can’t just pull a woman out of a hat”: A mixed-methods study on journalistic drivers of women’s representation in political news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 101(3), 679–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, J., Muthotho, I., & Mohamed, R. (2022). Media framing women’s participation in decision-making in East Africa: A case of South Sudan women in decision making. Advances in Journalism and Communication, 10(4), 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, E., Tarasevich, S., Xiao, L., Alhaddadeh, H., & Kiousis, S. (2024). Gender, politics, and the glass ceiling: Comparative analysis of male and female politicians’ agenda-building efforts in the U.S. primaries. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 19(4), 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, K. (2014). Women in media: A critical introduction. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2005). The glass cliff: Evidence that women are over-represented in precarious leadership positions. British Journal of Management, 16(2), 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- SANEF. (2019). South Africa’s 2019 elections: Handbook for journalists [Handbook]. Available online: https://sanef.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/190226-SANEF-South-Africa-Elections-2019-Handbook-for-Journalists.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- SANEF (with MMA). (2024). SANEF: South Africa’s 2024 elections—Mitigating online risks [Risk/mitigation brief]. Available online: https://sanef.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/SANEF-Mitigating-Online-Risks-for-the-2024-Elections.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Sazali, H., & Basit, L. (2020). Meta-analysis of women politician portrait in mass media frames. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 36(2), 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, G. W. (1999). Gendered citizenship: South Africa’s democratic transition and the construction of a gendered state. Gender & Society, 13(3), 287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Sisimayi, T. P., Muzorewa, T. T., & Muperi, J. T. (2024). Unveiling layers of inclusion in political spaces: A multidimensional exploration of inclusion in Zimbabwe. AJIS: African Journal of Inclusive Societies, 4(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobben, D., & Rawjee, V. P. (2013, October). Ethnic media and identity construction: The representation of women in an ethnic newspaper in South Africa. In International conference on human and social sciences (Vol. 2, pp. 20–22). MCSER. [Google Scholar]

- Steeves, H. L. (1987). Feminist theories and media studies. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 4(2), 95–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, L. (2014). Feminist media theory. In The handbook of media and mass communication theory (pp. 359–379). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Tembo, N. M. (2024). Women, political violence, and the production of fear in Malawian social media texts. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 26(1), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatelo, M. T. (2025). Visual representation of black women’s empowerment in online political advertisements: A case study of South Africa. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M., Harell, A., Rijkhoff, S. A., & Gosselin, T. (2021). Gendered news coverage and women as heads of government. Political Communication, 38(4), 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornham, S. (2007). Women, feminism and media. Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tiessen, R. (2008). Small victories but slow progress: An examination of women in politics in Malawi. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 10(2), 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchman, G. (1978). The symbolic annihilation of women by the mass media. In G. Tuchman, A. K. Daniels, & J. Benét (Eds.), Hearth and home: Images of women in the mass media (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zoonen, L. (1994). Feminist media studies: Key debates. Media, Culture & Society, 16(2), 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, S. C., & Emerson, M. O. (2000). Neoliberalism and feminist media activism: Contradictions and challenges. Feminist Review, 64, 128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, K., & Holland, J. (2014). Leadership and the media: Gendered framings of Julia Gillard’s “sexism and misogyny” speech. Australian Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigomo, K. (2022). Virtue, motherhood and femininity: Women’s political legitimacy in Zimbabwe. Journal of Southern African Studies, 48(3), 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbabwe Gender Commission. (2018). Preliminary election monitoring report [Election monitoring]. Available online: https://kubatana.net/2018/08/17/zimbabwe-gender-commission-preliminary-election-monitoring-report-2018-harmonised-elections (accessed on 6 January 2026).

| Criteria | Study Focus/Phenomenon of Interest | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion Criteria |

| Ensures that all included works directly address the central re-search questions and provide empirical or analytical evidence on gendered framing patterns. |

Geographic Focus:

| Focuses on a geographically and culturally coherent region where media structures and gender politics share post-colonial and socio-political dynamics. | |

Time Frame:

| Captures a 25-year period encompassing shifts from legacy to digital and social media environments, reflecting evolving journalistic practices and gender discourses. | |

Publication Type:

| Combines rigorous academic sources with validated practitioner-based monitoring reports to strengthen contextual and applied insights. | |

Language:

| Ensures consistency and accessibility of analysis across regional and international scholarly and professional audiences. | |

Research Design:

| Allows for triangulation between interpretive and descriptive findings, enhancing validity and comprehensive understanding. | |

| Exclusion Criteria | Non-peer-reviewed Sources:

| Excluded due to limited methodological reliability and absence of systematic analysis. |

Grey Literature Without Methodological Detail:

| Only methodologically robust grey sources were retained to maintain quality and replicability. | |

Studies Outside the Time Frame or Geographic Scope:

| Ensures contextual comparability, contemporary relevance, and focus on Southern African media systems. | |

Irrelevant Focus:

| Maintains alignment with the study’s aim to examine the media as a site of symbolic gender construction. |

| Search Category | Source/Database | Search String/Query Used | Purpose and Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peer-reviewed literature | Scopus | (“women politicians” OR “women political leaders” OR “female candidates” OR “women in politics”) AND (frameOR “media representation” OR portray OR coverage OR discourse) AND (election OR campaign) AND (“Southern Africa” OR “South Africa” OR Zimbabwe OR Malawi OR Zambia OR Lesotho OR Namibia OR Botswana) AND (media OR “news media” OR “social media” OR online OR print OR broadcast) | To retrieve internationally indexed journal articles on media framing of women politicians during elections in Southern Africa. |

| Peer-reviewed literature | Google Scholar | Same core string as above, adapted to Google Scholar syntax and filters (date range 2000–2025; English language) | To capture a broader range of peer-reviewed outputs, including regional journals, theses, and book chapters under-represented in Scopus. |

| Grey literature (media monitoring) | Media Monitoring Africa (MMA) | site:mediamonitoringafrica.org (gender OR women) AND (election OR “media performance”) | To identify election monitoring briefs and longitudinal reports on gender representation in South African media. |

| Grey literature (gender advocacy) | Gender Links | site:genderlinks.org.za (media OR “news coverage”) AND (election OR politics) | To retrieve gender audits, election coverage reports, and regional monitoring studies across Southern Africa. |

| Grey literature (media freedom & policy) | MISA | site:data.misa.org women AND election AND coverage (Zimbabwe OR Zambia) | To capture policy-oriented and monitoring reports on election coverage and gender in the media, particularly in Zimbabwe and Zambia. |

| Grey literature (journalism practice & safety) | SANEF | site:sanef.org.za election AND (handbook OR module) AND gender OR safety | To identify practitioner-focused guidelines, handbooks, and reports on election reporting, online harms, and gender-sensitive journalism. |

| Grey literature (global policy) | UNESCO Portal | “gender equality” AND media AND newsroom (Southern Africa filter where available) | To include international policy and normative frameworks relevant to gender, media, and newsroom practices in the Southern African context. |

| Code | Title | Author(s) | Year | Type | Methodology (as Stated) | Relevance/Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Online News Media, Religious Identity and Their Influence on Gendered Politics: Observations from Malawi’s 2014 Elections | Gunde, A. | 2015 | Journal | Qualitative textual/media analysis | Directly links religious discourse & gendered framing in election news. |

| P2 | Media Representation of Women in Politics and Media in Southern Africa | Mpofu, J. | 2017 | Journal | Review/critical analysis (NR specifics) | Regional synthesis on women’s political media representation. |

| P3 | Women, Political Violence, and the Production of Fear in Malawian Social Media Texts | Tembo, N. | 2024 | Journal | Qualitative social media text analysis | Platform-based gendered intimidation and fear frames in elections. |

| P4 | Media Representation of Women Parliamentary Candidates in Africa | Coffie, A.; Medie, P. | 2021 | Book chapter | Comparative review (NR specifics) | Continental evidence on frames applied to women candidates. |

| P5 | Independent Online and News24 Framing of Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma: A Case Study of the African National Congress 54th National Conference | Muringa, T.; McCracken, D. | 2021 | Journal | Framing analysis | Case-based evidence of competence/legitimacy frames in SA. |

| P6 | Exploring print media coverage of female politicians in Lesotho | Rapitse, S.; Bhila, T.; Mukurunge, T. | 2019 | Journal | Content analysis | Small-state perspective; stereotypical archetypes. |

| P7 | Metavoicing, trust-building mechanisms and partisan messaging: a study of social media usage by selected South African female politicians | Matsilele, T.; Nkoala, S. | 2023 | Journal | Social media/qualitative | How women politicians counter-frame online. |

| P8 | Ethnic Media and Identity Construction: The Representation of Women in an Ethnic Newspaper in South Africa | Soobben, D.; Rawjee, V.P. | 2013 | Conf. paper | Qualitative media analysis | Adds ethnic/identity layer to representational frames. |

| P9 | Women making news: Gender and media in South Africa | Geertsema, M. | 2008 | Journal | Review/critical | Earlier SA newsroom context for gendered coverage. |

| P10 | Media representation of political leadership and governance in South Africa—press coverage of Jacob Zuma | Nkomo, S. | 2016 | PhD | Content/discourse analysis | Contextual baseline of SA political coverage norms. |

| P11 | The politician, the wife, the citizen, and her newspaper: Rethinking women, democracy, and media (ted) representatio | Adcock, C. | 2010 | Journal | Critical discourse | Classic on gendered tropes in political reporting. |

| P12 | Representation of SA Women Politicians in the Sunday Times (2004 Elections) | Katembo, T.K. | 2005 | PhD | Content analysis | Election-specific SA framing of women politicians. |

| P13 | Representation of black, young, women politicians in South African online news media: a case study of Lindiwe Mazibuko | Mannya, M.M. | 2013 | PhD | Online news analysis | Youth/age intersection with gender in SA coverage. |

| P14 | Examining the Gendered Narratives in News Coverage of Joyce Banda (Malawi) | Muringa, T.P.; Ndlovu, J. | 2026 | Journal | Content Analysis | Language patterns useful as comparative lens. |

| P15 | The Representation of the Female Politician in Online News Media Outlets: Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma and Theresa May. | Dos Santos, B.M. | 2021 | Thesis | Comparative media analysis | Cross-country read on similar frames. |

| P16 | Gender transformation and media representations: Journalistic discourses in three South African newspapers | Buiten, D. | 2009 | PhD | Discourse analysis | Newsroom discourses & gender; SA baseline. |

| P17 | Female politicians in South Africa—image and gender discourse | Kanjere, M.M. | 2019 | Journal | Discourse analysis | Image politics & gender coding in SA. |

| P18 | Women’s Political Representation in South Africa and Botswana | Olaitan, Z.M. | 2024 | Book chapter | Policy/representation analysis | Institutional context shaping media narratives. |

| P19 | Representation of Female Politicians in Zimbabwean Print Media: 2000–2008 | Parichi, M. | 2016 | Thesis | Content analysis | Longitudinal Zim print election framing. |

| P20 | Mass Media Coverage of Election Campaigns and Its Influence on the Voter Study of The 2004 Malawi General Elections | Chiwanda, M.G. | 2006 | Thesis | Content analysis | Early Malawi election-media baseline. |

| P21 | Emerging political narratives on Malawian digital spaces | Mutsvairo, B.; Ragnedda, M. | 2017 | Journal | Digital discourse | Online narratives around politics & gender. |

| P22 | Empowering Malawi’ s girls: Media as a tool for developing equal rights and social standing. | Lundqvist, M. | 2024 | Report/Book (NR) | NR | Gendered media ecology; context for frames. |

| P23 | Small victories but slow progress: An examination of women in politics in Malawi. | Tiessen, R. | 2008 | Journal | Policy/participation analysis | Participation context that media reflects/amplifies. |

| P24 | ‘No Flowers for the New Boss’: Interrogating Malawian Newspapers Political Cartoon Stereotypical Representations of a Woman Anti-Corruption Bureau Director | Chandilanga, H.C.; Chikaipa, V. | 2024 | Journal | Semiotic analysis | Visual/cartoon frames targeting women leaders. |

| P25 | The loving heart of a mother or a greedy politician?: media representations of female presidents in Liberia and Malawi. | Sihvonen, E. | 2016 | Thesis/Report | Media representation analysis | “Mother/greedy” binary; transferable frame family. |

| P26 | “Women, media and culture in democratic Malawi.” Political Transition and Inclusive Development in Malawi. | Kayuni, H.M. | 2016 | Book chapter | Cultural/media analysis | Cultural repertoire that underpins frames. |

| P27 | interest groups and the promotion of women participation in Zambia’s political processes: case of Zambia national women’s lobby (1991–2018) | Lubinda, C. | 2021 | PhD | Policy/participation (NR media) | Context on party structures & representation. |

| P28 | Caring mother or weak politician? A semiotic analysis of editorial cartoon representations of President Joyce Banda in Malawian newspapers | Chikaipa, V. | 2019 | Journal | Semiotic/cartoon analysis | Visual gendered archetypes. |

| P29 | Geisler, Gisela. “Troubled sisterhood: women and politics in Southern Africa: case studies from Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana.” | Geisler, G. | 1995 | Journal | Political analysis | Early political culture shaping media frames. |

| P30 | investigating the influences of gender and qualifications on political leadership in Zambia; a case study of Chingola district | Chinyama, A. | 2024 | PhD | Case study (NR media) | Leadership perceptions that media echo. |

| P31 | Female political representation in Zambia: a study of four political parties’ policies and perspectives on party gender quotas and reserved seats adoption | Katongo, C.N. | 2017 | PhD | Policy analysis | Institutional drivers of visibility/framing. |

| P32 | Women, media and democracy: News coverage of women in the Zambian press. | Chimba, M.D. | 2006 | Thesis | Content analysis | Historic Zambian press patterns re women. |

| P33 | Phiri, Sam. “Political communication among female candidates and women electorates in Zambia.” Women’s Political Communication in Africa: Issues and Perspectives | Phiri, S. | 2020 | Book chapter | Qualitative (NR specifics) | Communication strategies amid biased media. |

| P34 | Blogging, feminism and the politics of participation: “The case of Her Zimbabwe.” In Digital activism in the social media era: Critical reflections on emerging trends in Sub-Saharan Africa | Mpofu, S. | 2016 | Book chapter | Digital activism analysis | Counter-framing & agency online. |

| P35 | “A reflection on the women in Zimbabwean politics through gender lenses.” | Manyeruke, C. | 2018 | Journal | Policy/media (NR) | Country context; links to delegitimising frames. |

| P36 | Unveiling layers of inclusion in political spaces: “A multidimensional exploration of inclusion in Zimbabwe.” | Sisimayi, T.P.; et al. | 2024 | Journal | Inclusion analysis | Structural inclusion intersecting with media narratives. |

| P37 | “We are not Ready for a ‘she’ President”: Navigating Media Framing of Women Presidential Hopefuls. | Muringa, T.P.; Sanele, G.J.; Aiseng, K. | 2024 | Journal | Framing analysis | Explicit “glass-cliff/competence” narratives in SA. |

| P38 | South African Parliament and blurred lines: The ANC Women’s League and the African National Congress’ gendered political narrative | Makhunga, L.D. | 2014 | Journal | Political/gender narrative | Party discourse feeding media angles. |

| P39 | Discrimination against female politicians on social media: An analysis of tweets in the run-up to the July 2018 Harmonised Elections in Zimbabwe | Ncube, G.; Yemurai, G. | 2020 | Book chapter | Social-media analysis | Abuse/harassment frames during elections. |

| P40 | Eternal mothers, whores or witches: The oddities of being a woman in politics in Zimbabwe | Ncube, G. | 2020 | Journal | Discourse analysis | Canonical Zimbabwean stereotype triad. |

| P41 | Theoretical paradoxes of representation and the problems of media representations of Zimbabwe in crisis | Mhiripiri, N.A.; Ureke, O. | 2018 | Journal | Representation theory critique | Crisis framing context. |

| P42 | Narratives of women in politics in Zimbabwe’s recent past: the case of Joice Mujuru and Grace Mugabe. | Mangena, T. | 2022 | Journal | Narrative/discourse analysis | Leadership legitimacy & gender. |

| P43 | Introduction: The Nexus Between Gender, Religion and the Media in Zimbabwean Electoral Politics. | Chirongoma, S.; Mavengano, E. | 2023 | Book chapter | Thematic analysis | Religion-media nexus shaping frames. |

| P44 | Participation of women in Zimbabwean politics and the mirage of gender equity. | Maphosa, M.; Tshuma, N.; Maviza, G. | 2015 | Journal | Policy/participation (NR) | Participation context linked to visibility. |

| P45 | Patriarchal politics, online violence and silenced voices: The decline of women in politics in Zimbabwe. | Mtero, S.; Parichi, M.; Madsen, D.H. | 2023 | Report | Mixed (NR specifics) | Online hostility impacting media narratives. |

| P46 | “Invisibility and hypervisibility” of ‘Ndebele women’in Zimbabwe’s media. | Mlotshwa, K. | 2018 | Journal | Media analysis | Intersectional erasure vs. spectacle. |

| P47 | African Women in Politics: An Analysis on the Challenges faced by Women in Politics in Zimbabwe | Gauti, C. | 2022 | Master’s | Review/analysis | Practitioner insights on barriers mirrored in media. |

| P48 | African feminist activism and democracy: Social media publics and Zimbabwean women in politics online. | Chikafa-Chipiro, R. | NR | Book/Chapter | Digital publics analysis | Counter-publics & counter-frames. |

| P49 | Misogyny, social media and electoral democracy in Zimbabwe’s 2018 elections. | Mateveke, P.; Chikafa-Chipiro, R. | 2020 | Book chapter | Social media/content | Election-time online gendered attacks. |

| P50 | The Zimbabwe political space: An analysis of the barriers to women’s participation in electoral processes?. | Mutizwa, A. et al. | 2024 | Journal | Policy/participation | Structures that shape media salience & frames. |

| P51 | The female body and voice in audiovisual political propaganda jingles: the Mbare Chimurenga Choir women in Zimbabwe’s contested political terrain. | Ngoshi, H.T.; Mutekwa, A. | 2013 | Journal | AV semiotics | Audiovisual tropes of femininity/power. |

| P52 | Virtue, motherhood and femininity: Women’s political legitimacy in Zimbabwe. | Zigomo, K. | 2022 | Journal | Discourse analysis | Legitimacy narratives (virtue/motherhood). |

| P53 | Engendering politics & parliamentary representation in Zimbabwe | Dube, T. | 2013 | Report/NR | NR | Parliamentary gender context tied to media. |

| P54 | “Meaning in the Service of Power”: A Marxist Analysis of Media Discourse on Presidential Elections in South Africa | Muringa, T. P., & Adjin-Tettey, T. D. | 2025 | Journal | Content Analysis | Contemporary update on gendered AV framing. |

| P55 | Women’s Representation in African Politics: Beyond Numbers | Olaitan, Z.M. | 2024 | Book chapter | Policy/representation | Institutional backdrop to media visibility. |

| P56 | Visual Representation of Black Women’s Empowerment in Online Political Advertisements: A Case Study of South Africa | Thatelo, M.T. | 2025 | Journal | Visual/content analysis | Digital campaign visuals & empowerment frames. |

| P57 | Gendered spectacle: New terrains of struggle in South Africa | Lewis, D. | 2009 | Book chapter | Critical analysis | “Spectacle” lens for media treatment of women leaders. |

| P58 | Women and the remaking of politics in Southern Africa: Negotiating autonomy, incorporation and representation. | Geisler, G.G. | 2004 | Book | Political analysis | Macro-context for women’s leadership & its media reception. |

| Code | Title | Organisation/ Author | Year | Type | Methodology/ Indicators | Relevance/Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | South Africa: election coverage through a gender lens | Lowe Morna (Gender Links (with Media Monitoring Africa) | 2009 | Monitoring brief (election) | Media monitoring snapshot of election coverage; gender indicators | Early, widely cited baseline on gendered election coverage in SA. |

| G2 | Analysing South Africa’s media coverage of 2019 elections | Media Monitoring Africa (MMA) | 2019 | Election monitoring report | Content analysis across outlets; voice/source shares | Systematic evidence of voice gaps during elections; methods transparent. |

| G3 | 15 years of reporting South African elections: Same same but different | MMA | 2018 | Retrospective report | Longitudinal monitoring synthesis | Trends across democratic elections; contextualises gender patterns. |

| G4 | LGE21 Elections Report | MMA | 2022 | Election monitoring report | Content analysis & indicator tracking | Local-election specific coverage patterns incl. gender/voice. |

| G5 | Brief 1: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections | MMA | 2024 | Monitoring brief | Ongoing 2024 NPE tracking; issue mix & voice shares | Timely, methods disclosed; feeds into final 2024 synthesis. |

| G6 | Brief 3: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections | MMA | 2024 | Monitoring brief | As above | Adds mid-cycle data for longitudinal comparison. |

| G7 | Brief 5: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections | MMA | 2024 | Monitoring brief | As above | Captures late-campaign dynamics. |

| G8 | Brief 7: An analysis of media’s coverage of the 2024 South African elections | MMA | 2024 | Monitoring brief | As above | Captures immediate post-poll trends. |

| G9 | Gender Audit of the May 2019 South African Elections—Beyond Numbers | Gender Links | 2019 | Audit/monitoring | Gender voice/source shares; leadership outcomes | Directly quantifies women’s sourcing in election news (2014→2019). |

| G10 | Gender and Media Progress Study (GMPS)—regional overview | Gender Links (with MISA/GEMSA) | 2020 | Regional research programme | Standardised content analysis across SADC | Cross-country baseline for women’s presence in news; methods published. |

| G11 | GMPS South Africa report (2015) | Gender Links | 2015 | Country report | National indicators; longitudinal comparison (2010 → 2015) | Country-level benchmarks relevant to elections & political beats. |

| G12 | Guidelines on Media Coverage of Elections in the SADC Region | MISA (SADC) | 2012 | Normative guideline | Best-practice framework | Citable standard for evaluating reporting practices vis-à-vis gender. |

| G13 | Media Performance Review: Interim Report (May 2024) | MMA | 2024 | Interim review | Cross-outlet performance indicators | Complements briefs with consolidated metrics. (Counts toward 12 if replacing any brief. |

| G14 | SANEF: South Africa’s 2024 elections—mitigating online risks | SANEF (with MMA) | 2024 | Risk/mitigation brief | Online-harms taxonomy; platform risk indicators | Useful for “fear/hostility” frames and newsroom practice. (Use if swapping one brief.) |

| G15 | Zimbabwe Gender Commission: (2018) | ZGC | 2018 | Election monitoring | Observation-based indicators; gender focus | Regional comparator on women’s political participation & media. (Use if expanding set.) |

| Country/Scope | Number of Studies | Dominant Thematic Categories | Descriptive Notes on Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zimbabwe | 19 | Gendered delegitimisation and stereotyping; Online harassment and misogyny; Crisis and moral framing; Religion and political identity; Digital counter-publics and feminist resistance | The most extensive national corpus. Research foregrounds print and digital media, elections, symbolic violence (mother/witch/whore tropes), online abuse, and leadership legitimacy. Dominant methodologies include discourse analysis, content analysis, semiotics, and social media studies. |

| South Africa | 14 | Gendered framing of leadership competence; Political legitimacy and authority; Media ideology and spectacle; Visual and digital political communication; Glass-cliff narratives | A methodologically diverse body of work spanning print, online, audiovisual, and visual advertising. Strong engagement with competence framing, ideological power, newsroom cultures, and explicit narratives questioning women’s suitability for leadership. |

| Malawi | 10 | Religious and cultural framing; Gendered intimidation and fear; Visual satire and cartoons; Digital political narratives; Leadership symbolism | Research concentrates on election periods, religious discourse, cartoons, and social media environments. Emphasis is placed on fear production, moral evaluation, and symbolic attacks on women leaders, particularly through visual and semiotic genres. |

| Zambia | 6 | Political participation and visibility; Institutional barriers and quotas; Leadership perceptions; Media–politics interface | Predominantly policy- and participation-oriented studies. Media framing is often discussed indirectly, with attention to how party structures, qualifications, and institutional arrangements shape women’s visibility and public legitimacy. |

| Botswana | 2 | Institutional representation; Gender and political inclusion | Appears mainly in comparative or regional political analyses. Media representation is addressed indirectly through institutional and governance-focused discussions of women’s political participation. |

| Lesotho | 1 | Stereotypical archetypes in print media; Gendered visibility | A single empirical content analysis offering a small-state Southern African perspective on stereotypical portrayals of women politicians in print media. |

| Southern Africa (Regional, multi-country) | 3 | Regional gendered media patterns; Political culture and representation; Media and gender power relations | Regional syntheses and macro-analyses situating national findings within shared Southern African historical, cultural, and political contexts shaping women’s media representation. |

| Africa (Continental comparative) | 2 | Comparative gendered framing; Moral and symbolic binaries in leadership representation | Comparative studies examining recurring frames applied to women politicians across African contexts, including transferable tropes such as virtue, motherhood, and moral legitimacy. |

| Cross-national (Africa–Global comparison) | 1 | Transnational gendered framing; Portability of competence and femininity narratives | Explicit cross-national media analysis tracing how similar gendered frames travel across political systems beyond the African continent. |

| Category | Sub-Category/Variable | n | % | Interpretive Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 4.2.6 Theoretical or Conceptual Frameworks Used | Framing Theory (incl. media frames/agenda) | 28 | 48.3 | Core conceptual model used to analyse narrative construction and agenda-setting around women politicians. |

| Feminist Media/Gender Theory | 24 | 41.4 | Widely combined with Framing Theory to explore gendered power, visibility, and symbolic representation. | |

| Political communication/discourse/rhetoric | 10 | 17.2 | Applied in studies analysing campaign language, political discourse, and rhetoric around leadership. | |

| Atheoretical/implicit framework | 12 | 20.7 | Most common in NGO/grey reports; reflects descriptive monitoring with limited theoretical scaffolding. | |

| Observation: | The field demonstrates strong theoretical anchoring, with co-usage of Framing and Feminist Media Theory prevalent across the majority of studies. | |||

| Section 4.2.7 Journals/Sources of Publication | Communication/Media journals | 18 | — | Dominant source type, reflecting academic consolidation of gender–media studies. |

| Gender/Politics/Area studies journals | 14 | — | Highlights the field’s interdisciplinary orientation bridging media and governance. | |

| University theses/dissertations | 10 | — | Indicates strong postgraduate engagement and academic pipeline growth. | |

| NGO/IGO monitors (MMA, Gender Links, MISA, SANEF, UNESCO) | 12 | — | Practitioner outputs vital for real-time evidence and policy advocacy. | |

| Conference proceedings/edited volumes | 4 | — | Reflects scholarly dissemination and emerging debates in regional research forums. | |

| Section 4.2.8 Population/Unit of Analysis | Media texts (news stories, headlines, social posts, visuals) | 49 | 84.5 | Media text analysis dominates, with focus on representation, imagery, and discourse patterns. |

| Journalists/editors/newsrooms | 6 | 10.3 | Investigates newsroom practices, gatekeeping, and gender dynamics in production. | |

| Audiences/users | 3 | 5.2 | Minimal exploration of public reception or reader interpretation, showing a clear research gap. | |

| Section 4.2.9 Data Collection Techniques (Primary) | Systematic text coding (content/discourse/semiotic) | 41 | 70.7 | Main methodological approach; supports qualitative rigour and cross-study comparability. |

| Organisational monitoring indicators (share-of-voice, source gender, topic mix) | 12 | 20.7 | Common in NGO datasets; introduces measurable gender metrics. | |

| Interviews/focus groups (journalists/actors) | 8 | 13.8 | Adds qualitative depth through experiential and institutional perspectives. | |

| Surveys (audiences/journalists) | 4 | 6.9 | Provides quantitative perception data; rarely integrated with textual evidence. | |

| Social media analytics (API/scrape/hashtag tracking) | 6 | 10.3 | Emerging trend; captures digital discourse and platform-based gender bias. | |

| Section 4.2.10 Funding & Institutional Affiliations | Funding disclosed | 17 | 29.3 | Low disclosure rate suggests limited transparency and formal funding channels. |

| Academic affiliations (lead authors) | 46 | 79.3 | Indicates academic leadership in theory-driven inquiry. | |

| NGO/IGO institutional authorship | 12 | 20.7 | Signifies active contribution from civil society and intergovernmental agencies in gender–media monitoring. | |

| General Observation: | The field reflects a mature, interdisciplinary research ecosystem dominated by text-based qualitative analysis and robust theoretical foundations, yet constrained by limited audience research, experimental designs, and funding transparency. | |||

| Research Question | Theme | Description/Analytical Insights | Illustrative Evidence (Countries & Sources) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1: How do the media frame women politicians in Southern Africa? | Cultural–Patriarchal Archetypes (Mother/Whore/Witch) | Women politicians are framed through patriarchal and culturally resonant archetypes that condition their legitimacy on moral respectability or domestic conformity. Assertive or ambitious women are labelled as “unruly,” “witches,” or “whores,” while maternal or submissive figures are celebrated as “Amai” (mother). These frames draw on deep-rooted gender ideologies that define femininity through subservience and virtue, undermining leadership authority. | Zimbabwe: Ncube (2020); Zigomo (2022)—“Amai/hure” dichotomy; Malawi: Gunde (2015); Tembo (2024)—religious metaphors (“Sesa Joyce Sesa”); South Africa: Muringa et al. (2024); Dos Santos (2021)—“not ready for a woman president” discourse. |

| Competence Erasure and Conditional Leadership (“Political Glass Cliff”) | Women’s political competence is overshadowed by focus on family life, emotionality, or appearance. Coverage often links women’s rise to periods of instability, implying they are appointed to fix crises rather than to lead in stable times. This “glass cliff” framing constructs women’s leadership as conditional and temporary, eroding perceptions of authority and sustainability. | Malawi: Chikaipa (2019); Tembo (2024)—Banda framed as emotional and crisis-bound; South Africa: Muringa and McCracken (2021)—Dlamini-Zuma depicted as divisive; Zambia: Phiri (2020)—female leaders assigned tokenistic visibility. | |

| Fear Production and Symbolic Violence | Political and discursive violence—including online harassment, exclusionary narratives, and sexualised trolling—are used to intimidate women politicians. Such violence reinforces “the female fear factory” (Gqola), discouraging participation and re-inscribing women’s vulnerability. Media and social networks serve as amplifiers of symbolic control and public humiliation. | Malawi: Tembo (2024)—online harassment by DPP supporters; Zimbabwe: Ncube and Yemurai (2020)—Twitter-based abuse; Zambia: Lubinda (2021)—exclusion of women in digital campaigning; South Africa: Matsilele and Nkoala (2023)—gendered trolling on political Twitter. | |

| RQ2: What reporting practices reinforce or challenge gendered frames such as the “political glass cliff”? | Reinforcing Practices: Gendered Sourcing, Visibility and Lexical/Visual Bias | Newsrooms predominantly quote male sources and experts, granting women limited issue-based voice. Visual framing—through domestic imagery, emotive photos, and “iron lady” or “mother” headlines—reinforces stereotypes and undermines policy credibility. These routine practices reproduce patriarchal hierarchies and diminish women’s perceived competence. | Gender Links (2024); Media Monitoring Africa (2024c)—<25% women’s voices in political news; Lesotho: Rapitse et al. (2019)—sexist print imagery; Zimbabwe: Parichi (2016)—focus on appearance over substance; South Africa: Dos Santos (2021). |

| Structural Legitimation of Bias: Party, Religious and Cultural Gatekeeping | Political parties, religious figures, and traditional authorities validate gendered framings by linking leadership to cultural propriety. Party women’s wings are sidelined; events such as beauty shows or appliance donations symbolically tie women to domesticity. Religion is invoked to assess women’s purity or virtue, reinforcing exclusionary media narratives. | Malawi: Gunde (2015); Kayuni (2016)—religion used to discredit Banda; Zimbabwe: Mangena (2022); Chirongoma and Mavengano (2023)—cultural leaders as arbiters of morality; South Africa: Lewis (2009)—patriarchal nationalism in coverage of women’s politics. | |

| Counter-Practices: Gender-Sensitive Journalism and Feminist Resistance | Advocacy-driven initiatives, especially by NGOs like Gender Links and MMA, promote balanced sourcing, gender-aware reporting, and training for journalists. Some women politicians use social media and feminist discourse to reclaim narratives, challenge stereotypes, and foreground competence. These emerging practices disrupt traditional framing but remain sporadic and institutionally fragile. | Gender Links (2024); Media Monitoring Africa (2024d); South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF, 2024)—newsroom gender policy tools; Malawi: Gunde (2015)—feminist counter-speech; Zimbabwe: Zigomo (2022); J. Mpofu (2017)—resistance through digital feminist activism; South Africa: Thatelo (2025). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Muringa, T.P.; Ndlovu, J. Media and Women Politicians in Southern Africa: A Systematic Review. Journal. Media 2026, 7, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010023

Muringa TP, Ndlovu J. Media and Women Politicians in Southern Africa: A Systematic Review. Journalism and Media. 2026; 7(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuringa, Tigere Paidamoyo, and James Ndlovu. 2026. "Media and Women Politicians in Southern Africa: A Systematic Review" Journalism and Media 7, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010023

APA StyleMuringa, T. P., & Ndlovu, J. (2026). Media and Women Politicians in Southern Africa: A Systematic Review. Journalism and Media, 7(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia7010023