Heuristic and Systematic Processing on Social Media: Pathways from Literacy to Fact-Checking Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Model

2.1. Foundational Literacy as Precursor to News Literacy

2.2. News Literacy in Social Media Environment

- Creation involves understanding how information is produced through journalistic, institutional processes, including data sourcing, verification, and transparency (Tully et al., 2011; Swart, 2023). Awareness of credible sourcing—such as diverse perspectives, traceable data, or disclosure of AI assistance—enables students to distinguish authentic content from manipulative or deceptive information (Hinsley & Holton, 2021).

- Circulation refers to awareness of how information flows through digital networks and algorithms. Literate users recognize how personalization systems and engagement metrics shape exposure and interpretation, cultivating what can be termed algorithmic awareness (Du, 2023; Edgerly, 2017; Loh et al., 2023).

- Participation encompasses civic and ethical engagement, such as commenting, sharing, or correcting misinformation. These practices illustrate participatory literacy, combining critical reasoning with empathy, respect, and accountability in digital discourse (Jenkins & Purushotma, 2009; Huber et al., 2022).

2.3. Systematic-Heuristic Processing Model in Digital Engagement

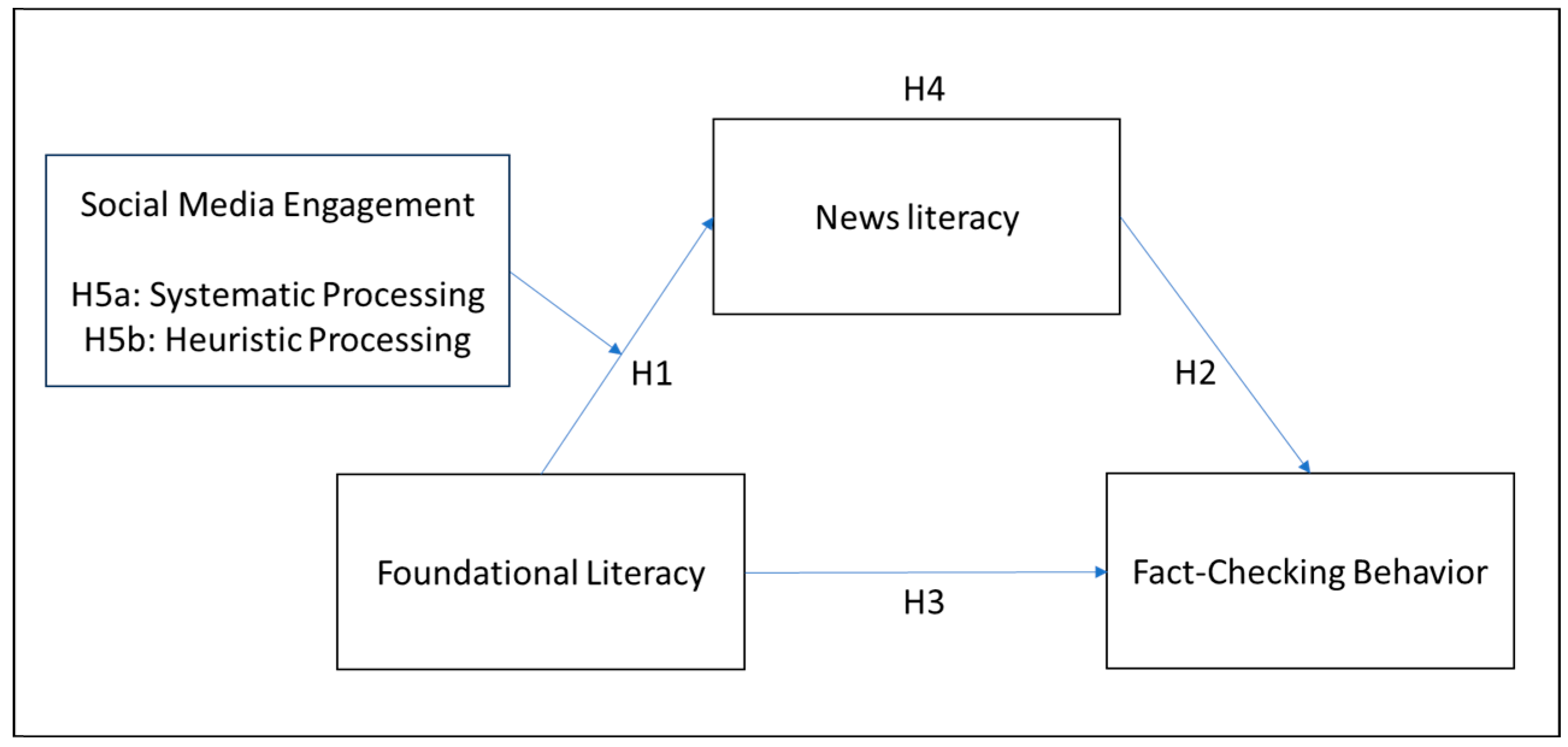

2.4. Proposed Moderated Mediation Model

2.5. Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Procedures and Measures

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

4.2.1. Mediation Effect of News Literacy

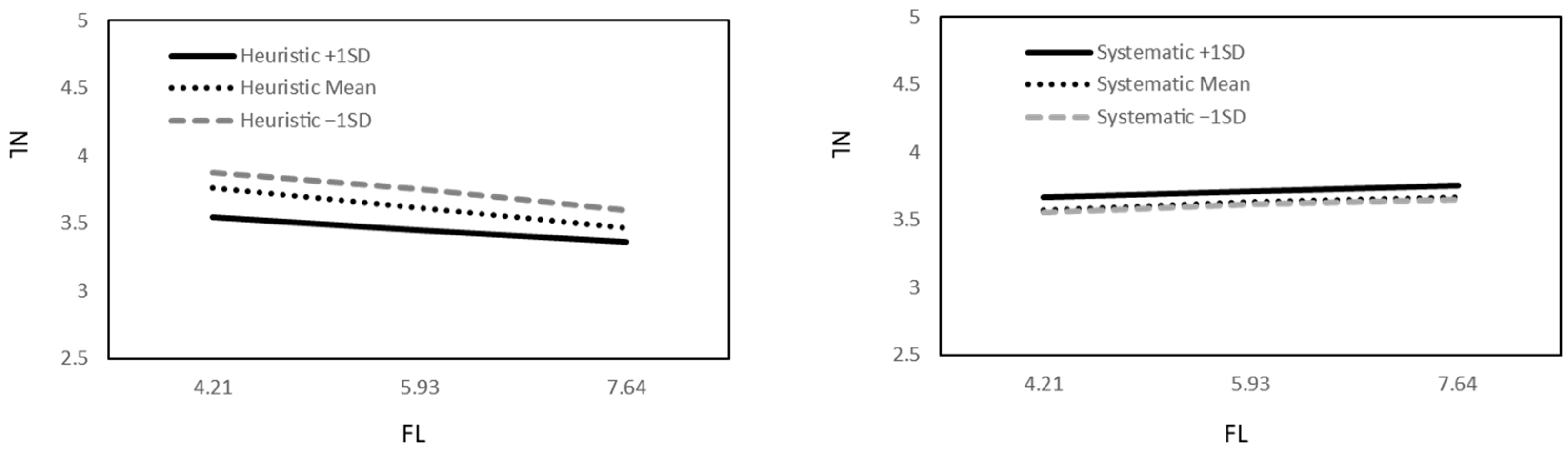

4.2.2. Moderated Effect of Heuristic Processing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashley, S., Maksl, A., & Craft, S. (2013). Developing a news media literacy scale. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 68, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, S., Maksl, A., & Craft, S. (2017). News media literacy and political engagement: What’s the connection. Journal of Media Literacy Education (JMLE), 9, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. (2022). Digital media trends: Gen Z news consumption. Deloitte Insights. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y. R. (2023). Personalization, echo chambers, news literacy, and algorithmic literacy: A qualitative study of AI-powered news app users. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 67, 246–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBS. (2025). Adult literacy test. Available online: https://literacy.ebs.co.kr/yourliteracy/literacyPlusTest (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Edgerly, S. (2017). Seeking out and avoiding the news media: Young adults’ proposed strategies for obtaining current events information. Mass Communication and Society, 20, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J. (2013). Media literacy, news literacy, or news appreciation? A case study of the News Literacy program at Stony Brook University. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator (JMCE), 69, 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, R. K. (2017). The ‘echo chamber’ distraction: Disinformation campaigns are the problem, not audience fragmentation. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinsley, A., & Holton, A. (2021). Fake news cues: Examining the impact of content, source, and typology of news cues on people’s confidence in identifying mis- and disinformation. International Journal of Communication, 15, 4984–5003. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, R. (2011). The state of media literacy: A response to Potter. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitch, H. (2014, October 1). The elite college students who can’t read books. The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/11/the-elite-college-students-who-cant-read-books/679945/?utm_source=copy-link&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=share (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Huber, B., Borah, P., & de Zúñiga, H. G. (2022). Taking corrective action when exposed to fake news: The role of fake news literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education (JMLE), 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S., Rashidin, M. S., & Jian, W. (2024). Effects of heuristic and systematic cues on perceived content credibility of Sina Weibo influencers: The moderating role of involvement. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H., & Purushotma, R. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. T., & Ewbank, A. D. (2018). Heuristics: An approach to evaluating news obtaining through social media. Knowledge Quest, 47, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Communications Commission. (2023). 2023 broadcasting media usage behavior survey. Korea Communications Commission. Available online: https://www.kcc.go.kr/user.do?mode=view&page=E04010000&dc=E04010000&boardId=1058&cp=6&boardSeq=59074 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Korea Press Foundation. (2024). 2024 media audience survey. Korea Press Foundation. Available online: https://www.kpf.or.kr/front/research/selfDetail.do?seq=595996 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Ku, K. Y., Kong, Q., Song, Y., Deng, L., Kang, Y., & Hu, A. (2019). What predicts adolescents’ critical thinking about real-life news? The roles of social media news consumption and news media literacy. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 33, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Hong, I. B. (2021). The influence of situational constraints on consumers’ evaluation and use of online reviews: A heuristic-systematic model perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C. E., Sun, B., & Weninger, C. (2023). Because I have my phone with me all the time: The role of device access in developing Singapore adolescents’ critical news literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 66, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksl, A., Ashley, S., & Craft, S. (2015). Measuring news media literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education (JMLE), 6, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, R. (2012). With Facebook, blogs, and fake news, teens reject journalistic ‘objectivity’. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 36, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, I. C., & Kormelink, T. G. (2015). Checking, sharing, clicking and linking: Changing patterns of news use between 2004 and 2014. Digital Journalism, 3, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailidis, P. (2008). Beyond cynicism: How media literacy can make students more engaged citizens [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland]. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S., Miller, S. A., Menard, P., & Bourrie, D. (2024). I’m not fluent: How linguistic fluency, new media literacy, and personality traits influence fake news engagement behavior on social media. Information & Management, 61, 103912. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrove, A. T., Powers, J. R., Rebar, L. C., & Musgrove, G. J. (2018). Real or fake? Resources for teaching college students how to identify fake news. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 25, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N., Arguedas, A. R., Robertson, C. T., Nielsen, R. K., & Fletcher, R. (2025, June). Digital news report 2025. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2025-06/Digital_News-Report_2025.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. C. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). 21st-century readers: Developing literacy skills in a digital world. PISA, OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, W. J. (2004). Theory of media literacy: A cognitive approach. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Shearer, E. (2023). News consumption across social media platforms in 2023. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Swart, J. (2023). Tactics of news literacy: How young people access, evaluate, and engage with news on social media. New Media & Society, 25, 505–521. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, M., Maksl, A., Ashley, S., Vraga, E. K., & Craft, S. (2011). Defining and conceptualizing news literacy. Journalism, 23, 1589–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraga, E., Tully, M., Kotcher, J., Smithson, A., & Broeckelman-Post, M. (2015). A multi-dimensional approach to measuring news media literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education (JMLE), 7, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Social Media Engagement |

|---|---|

| Heuristic processing | “I understand content mainly through titles, reading only superficially.” “I judge credibility based on follower counts or the number of ‘likes.’” “I make judgments based on my prior beliefs.” |

| Systematic processing | “I carefully read the full content to grasp the main ideas.” “I evaluate the logical validity of the arguments.” “I seek additional information before making judgments.” |

| Demographic Characteristics | n | Valid % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 105 | 52.5 |

| Women | 95 | 47.5 | |

| Grade | Freshmen | 33 | 16.5 |

| Sophomore | 56 | 28.0 | |

| Junior | 45 | 22.5 | |

| Senior | 66 | 33.0 | |

| Major 1 | Humanities/Social Science | 83 | 41.5 |

| Engineering | 62 | 31.0 | |

| Natural Sciences | 26 | 13.0 | |

| Arts, Performance, and Athletics | 22 | 11.0 | |

| Medical Sciences | 7 | 3.5 | |

| GPA | Below 2.0 | 4 | 2.0 |

| 2.00–2.49 | 2 | 1.0 | |

| 2.50–2.99 | 9 | 4.5 | |

| 3.00–3.49 | 32 | 16.0 | |

| 3.50–3.99 | 78 | 39.0 | |

| 4.00 | 56 | 28.0 | |

| Decline to answer | 19 | 9.5 | |

| 200 | 100 |

| Variables | M | SD | α | FL | NL | SP | HP | FCB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundational Literacy (FL) | 5.93 | 1.72 | ||||||

| News Literacy (NL) | 3.62 | 0.63 | 0.84 | 0.21 ** | ||||

| Systematic Processing (SP) | 2.41 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |||

| Heuristic Processing (HP) | 2.66 | 0.60 | 0.74 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.21 | ||

| Fact-Checking Behaviors (FCB) | 3.59 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.07 | 0.69 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.14 |

| β | SE | t | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating variable (NL) Model | 0.10 *** | ||||

| FL | 0.08 * | 0.03 | 2.96 | ||

| Dependent variable (FCB) Model | 0.49 *** | ||||

| FL | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.40 | ||

| NL | 0.75 *** | 0.06 | 13.04 | ||

| Effect | SE | t | CI | ||

| LL | UL | ||||

| Direct effect (FL → FCB) | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.40 | −0.07 | 0.01 |

| Effect | Boot SE | t | Boot CI | ||

| LL | UL | ||||

| Indirect effect (FL → NL → FCB) | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.15 | |

| β | SE | t | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating variable (NL) Model | 0.10 *** | ||||

| FL | 0.08 * | 0.03 | 2.96 | ||

| Effect | SE | t | CI | ||

| LL | UL | ||||

| FL × SP | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.09 | |

| FL × HP | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.10 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, Y.Y.; Woo, H. Heuristic and Systematic Processing on Social Media: Pathways from Literacy to Fact-Checking Behavior. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040198

Cho YY, Woo H. Heuristic and Systematic Processing on Social Media: Pathways from Literacy to Fact-Checking Behavior. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(4):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040198

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Yoon Y., and Hyunju Woo. 2025. "Heuristic and Systematic Processing on Social Media: Pathways from Literacy to Fact-Checking Behavior" Journalism and Media 6, no. 4: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040198

APA StyleCho, Y. Y., & Woo, H. (2025). Heuristic and Systematic Processing on Social Media: Pathways from Literacy to Fact-Checking Behavior. Journalism and Media, 6(4), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040198