Integrating Corpus Linguistics and Text Mining to Analyze European Media Coverage on China–EU Electric Vehicle Dispute

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. CL and Text Mining in CDA

2.2. The Corpus-Based CDA of China’s Images in the Media

2.3. Economic Nationalism and Green Protectionism: Motives Behind the EU’s EV Policies

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Analytical Methods

3.3. Analysis Procedure

4. Findings

4.1. Sentiment Analysis

4.2. Themes

4.2.1. Market Reaction

4.2.2. Trade War

4.2.3. China’s Response

4.2.4. Dialogue and Negotiation

4.3. Collocation Analysis

4.3.1. China as the Unfair-Subsidy Provider

4.3.2. China as the Threatener

4.3.3. China as the Negotiator

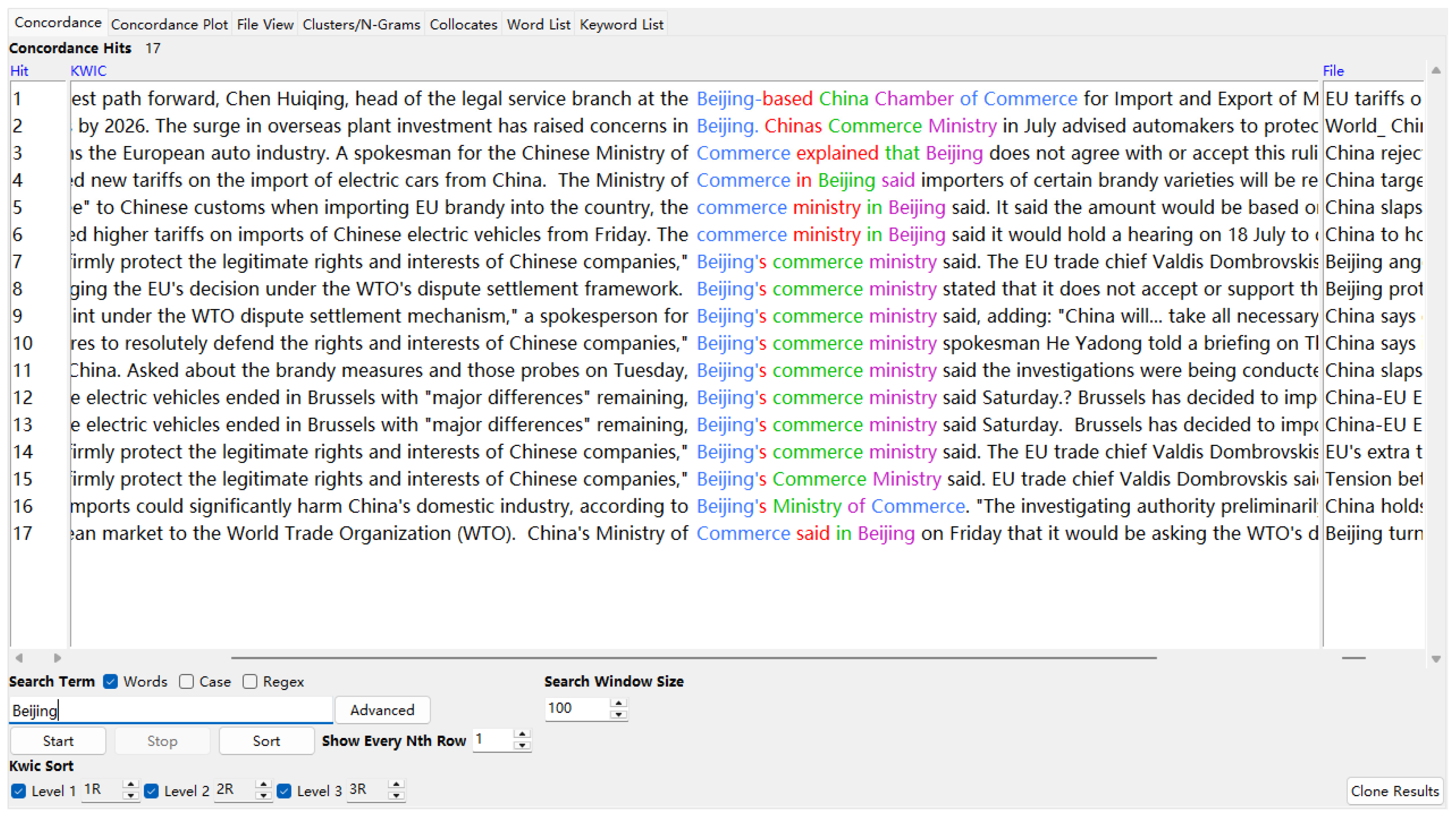

4.3.4. China as the Defender

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agence France Presse. (2024). VW rejects ‘detrimental’ EU tariffs on electric cars from China. Available online: https://hfhhi07fffe4c53724d36snvu6pfxp5wkv6u6kfacz.libproxy.ruc.edu.cn/document/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=2d3fed61-74cc-4ff2-b35e-b54d4e7a1f28&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A6CD8-PYH1-JBV1-X00P-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=10903&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=hcgmk&earg=sr0&prid=9acf19b1-4c7c-4fd4-b933-b5b6e8a557df (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- AutoCar. (2024). Big EU tariffs for Chinese EVs; EVs built in China face swingeing EU import taxes from next month under new plans. Available online: https://hfhhi07fffe4c53724d36snvu6pfxp5wkv6u6kfacz.libproxy.ruc.edu.cn/document/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=61e6b91a-7f69-40e2-a32f-5bfb550232ae&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A6C94-0FV1-DYTY-C1M7-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=412242&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=hcgmk&earg=sr0&prid=46014e17-58a9-4862-9b8c-113a9adc4020 (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Baker, P. (2012). Acceptable bias? Using corpus linguistics methods with critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies, 9(3), 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P. (2023). Using corpora in discourse analysis (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., KhosraviNik, M., Krzyżanowski, M., McEnery, T., & Wodak, R. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse & Society, 19(3), 273–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, M. (2024). Topic modelling in corpus-based discourse analysis: Uses and critiques. Discourse Studies, 27(4), 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, M., & Caple, H. (2014). Why do news values matter? Towards a new methodological framework for analysing news discourse in Critical Discourse Analysis and beyond. Discourse & Society, 25(2), 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfast Telegraph. (2024). China files WTO complaint against EU over tariffs on electric vehicles. Available online: https://hfhhi07fffe4c53724d36snvu6pfxp5wkv6u6kfacz.libproxy.ruc.edu.cn/document/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=9eeb2e9e-3f31-451a-ab58-b0303d1f98f3&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A6CP0-B0X1-JBNF-W501-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=400553&pdteaserkey=sr6&pditab=allpods&ecomp=hcgmk&earg=sr6&prid=44f233b6-3214-4f1d-a6b1-f677bcdc11b4 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Boulding, K. E. (1959). National images and international systems. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 3(2), 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, C., Tudorica, B., Andrei, J. V., Dusmanescu, D., Paraschiv, D., & Teodor, C. (2024). Sentiment analysis of global news on environmental issues: Insights into public perception and its impact on low-carbon economy transition. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 12, 1360304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Daily. (2024a). A balanced EV deal can help steady Sino-EU economic ties. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202411/25/WS6743c4f9a310f1265a1cf4c4.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- China Daily. (2024b). China’s anti-dumping probe into EU brandy does not target any specific EU member state: Minister. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202404/09/WS6614b3d0a31082fc043c0f85.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- China Daily. (2024c). EU should withdraw tariffs on Chinese electric cars. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202407/19/WS6699c146a31095c51c50edda.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- China Daily. (2024d). EU tariff decision on Chinese EVs denounced. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202406/12/WS6669bf4ba31082fc043cc275.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- China Daily. (2024e). Global backlash on EU tariffs. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202411/04/WS67282408a310f1265a1cb2e0.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Deloitte. (2024). Deloitte perspective: What is the impact of EU tariffs on electric vehicles in China? Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/cn/en/services/tax/perspectives/eu-tariffs-impact-on-chinese-evs.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- dpa-AFX. (2024). Beijing turns to WTO over EU’s tariffs on e-cars. Available online: https://hfhhi07fffe4c53724d36snvu6pfxp5wkv6u6kfacz.libproxy.ruc.edu.cn/document/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=f4304238-555d-413c-8737-b39d0be53c33&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A6CP1-MD41-DXCW-C420-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=400568&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=hcgmk&earg=sr0&prid=f14f91e3-4463-4d57-b4f7-26b011bdad1c (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- dpa international. (2024). Germany’s auto sector urges opposition to EU tariffs on Chinese cars. Available online: https://hfhhi07fffe4c53724d36snvu6pfxp5wkv6u6kfacz.libproxy.ruc.edu.cn/document/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=f7757e7b-cefd-42c8-bb16-f35c6e8c0c05&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A6D3G-CFY1-JB0G-F27H-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=144245&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=hcgmk&earg=sr0&prid=5a6d669a-5695-4332-bff7-386e72419374 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Elsoufy, A. M. (2024). Media bias through collocations: A corpus-based study of Egyptian and Ethiopian news coverage of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2019). EU-China—A strategic outlook. European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2019-03/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- European Commission. (2024a). Commission investigation provisionally concludes that electric vehicle value chains in China benefit from unfair subsidies. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3231 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- European Commission. (2024b). EU imposes duties on unfairly subsidised electric vehicles from China while discussions on price undertakings continue. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_5589 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Freeman, D. (2022). The EU and China: Policy perceptions of economic cooperation and competition. Asia Europe Journal, 20(3), 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganter, S. A., & Loeblich, M. (2021). Discursive media institutionalism: Assessing Vivien A. Schmidt’s framework and its value for media and communication studies. International Journal of Communication, 15, 2281–2300. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiretti, F. (2024). EU tariffs must be part of a multipronged strategy. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/11/eu-tariffs-must-be-part-of-a-multipronged-strategy.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Hauge, J., Houtzager, B., & Hörmann, A. J. (2025). The new economic nationalism: Industrial policy and national security in the United States, China, and the European Union. Geoforum, 166, 104382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. (2023). China’s image in the GCC mainstream English newspapers: A corpus-based critical discourse analysis. Critical Arts, 37(6), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, C. (2024). China opportunity or China threat? A corpus-based study of China’s image in Australian news discourse. Social Semiotics, 34(5), 808–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S. (2002). Corpora in applied linguistics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, C., & Gilbert, E. (2014, June 1–4). VADER: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, (Vol. 8, Issue 1). Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invezz. (2024). Beijing protests EU tariffs on Chinese EVs, files complaint with WTO. Available online: https://hfhhi07fffe4c53724d36snvu6pfxp5wkv6u6kfacz.libproxy.ruc.edu.cn/document/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=b72e017f-bda7-47e2-897f-148a2202bba1&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A6D9H-7KY1-F03F-K4WB-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=488569&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=hcgmk&earg=sr0&prid=15c3baad-8f3d-4450-8a74-11eb7114d80e (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Koichi, H. (2016). A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis: KH coder tutorial using Anne of green gables (part I). Ritsumeikan Social Sciences Review, 52(3), 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kratz, A., Zenglein, M. J., Brown, A., Sebastian, G., & Meyer, A. (2024). Dwindling investments become more concentrated—Chinese FDI in Europe: 2023 update. Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). Available online: https://merics.org/en/report/dwindling-investments-become-more-concentrated-chinese-fdi-europe-2023-update (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Lai, S. (2023). Not seeing eye to eye: Perception of the China-EU economic relationship. Asia Europe Journal, 21(2), 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. (2019). How are ‘immigrant workers’ represented in Korean news reporting?—A text mining approach to critical discourse analysis. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 34(1), 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. (2024). Towards a ‘synergy’ of text mining and critical discourse analysis: A corpus-assisted discourse study of imagining China in Hong Kong political discourse. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 39(2), 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., & Li, C. (2017). Competing discursive constructions of China’s smog in Chinese and Anglo-American English-language newspapers: A corpus-assisted discourse study. Discourse & Communication, 11(4), 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M., & Ghanem, S. I. (2001). The convergence of agenda setting and framing. In S. D. Reese, O. H. Gandy, & A. E. Grant (Eds.), Framing public life (pp. 67–82). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery, T., & Hardie, A. (2012). Corpus linguistics: Method, theory, and practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlićević, D. (2022). Contesting China in Europe: Contextual shift in China-EU relations and the role of “China threat”. In D. Pavlićević, & N. Talmacs (Eds.), The China question (pp. 67–92). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonnaud, G. (2025). Powering the EU’s future: Strengthening the EU battery industry. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/767214/EPRS_BRI(2025)767214_EN.pdf#:~:text=While%20the%20EU%20battery%20sector%20enjoys%20strong%20support,third%20countries%20and%20high%20energy%20and%20labour%20costs (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Riker, W. H. (1986). The art of political manipulation. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rühlig, T. N., Jerdén, B., van der Putten, F.-P., Seaman, J., Otero-Iglesias, M., & Ekman, A. (2018). Political values in Europe-China relations. The Swedish Institute of International Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A. H. Y. (2011). Ideological collocation and the recontexualization of Wahhabi-Saudi Islam post-9/11: A synergy of corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 22(3), 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Lee, C.-C., & Huang, Z. (2021). The news prism of nationalism versus globalism: How does the US, UK and Chinese elite press cover ‘China’s rise’? Journalism, 22(8), 2071–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L. (2021). Transitive representations of China’s image in the US mainstream newspapers: A corpus-based critical discourse analysis. Journalism, 22(3), 804–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. (2024). China to hold hearing into brandy imports as tension grows with EU over tariffs on EVs. Available online: https://hfhhi07fffe4c53724d36snvu6pfxp5wkv6u6kfacz.libproxy.ruc.edu.cn/document/?pdmfid=1000516&crid=73f18cdb-2501-4fc9-b9d7-b76d8d4e7792&pddocfullpath=%2Fshared%2Fdocument%2Fnews%2Furn%3AcontentItem%3A6CDH-BW81-DY4H-K1VT-00000-00&pdcontentcomponentid=138620&pdteaserkey=sr0&pditab=allpods&ecomp=hcgmk&earg=sr0&prid=a7b8f6aa-451e-4e72-8cec-3da07c41f515 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Vaara, E., Aranda, A. M., & Etchanchu, H. (2024). Discursive legitimation: An integrative theoretical framework and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 50(6), 2343–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, T. A. (1995). Discourse analysis as ideology analysis. In Language & peace. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, T. A. (2001). Critical discourse analysis. In D. Schiffrin, D. Tannen, & H. E. Hamilton (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 349–371). Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, T. A. (2009). News, discourse, and ideology. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen, & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vela Almeida, D., Kolinjivadi, V., Ferrando, T., Roy, B., Herrera, H., Gonçalves, M. V., & Van Hecken, G. (2023). The “greening” of empire: The European green deal as the EU first agenda. Political Geography, 105, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Leyen, U. (2023a). 2023 State of the union address by President von der Leyen. European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_4426 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- von der Leyen, U. (2023b). Speech by president von der Leyen at the European China Conference 2023 organised by the European Council on Foreign Relations and the Mercator Institute for China Studies. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_5851 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Wang, G. (2018). A corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis of news reporting on China’s air pollution in the official Chinese English-language press. Discourse & Communication, 12(6), 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Liu, Y., & Tu, S. (2023). Discursive use of stability in New York Times’ coverage of China: A sentiment analysis approach. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Ma, X. (2021). Representations of LGBTQ+ issues in China in its official English-language media: A corpus-assisted critical discourse study. Critical Discourse Studies, 18(2), 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, L. R. (1995). Reported speech in journalistic discourse: The relation of function and text. Text & Talk, 15(1), 129–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, R. (2011). Critical discourse analysis: Overview, challenges, and perspectives. In G. Andersen, & K. Aijmer (Eds.), Pragmatics of society (pp. 627–650). DE GRUYTER. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Huan, C., & García Marrugo, A. (2024). Fair or biased? A corpus-based study of Australia’s early COVID-19 media representation of China. Social Semiotics, 35(3), 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Nartey, M., & Chen, J. (2024a). A critical discourse analysis of resistance to climate change in China’s English-language news media. Asian Studies Review, 48(3), 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Tay, D., & Yue, Q. (2024b). Media representations of China amid COVID-19: A corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis. Media International Australia, 191(1), 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L., Chen, W., Li, X., Zuo, W., & Yin, M. (2019). A survey of sentiment analysis in social media. Knowledge and Information Systems, 60(2), 617–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., & Wu, D. (2017). Media representations of China: A comparison of China daily and financial times in reporting on the belt and road initiative. Critical Arts, 31(6), 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region/Country (Number) | Name (Number of Articles) |

|---|---|

| EU (2) | EurActiv (12), EuroNews (4) |

| Baltic States (3) | Impact News Service (7), Impact Financial News (7), The Baltic Times (1) |

| the UK (20) | Alliance News (11), Just Auto (8), Autocar (6), Invezz (6), MarketLine NewsWire (6), Business World Agency (5), Daily Mirror (3), Proactive Investors (3), The Guardian (3), The Independent (3), Belfast Telegraph (2), Mail Online (2), Silicon UK (2), The Telegraph (2), GB News (1), Just Drinks (1), Motor Trader (1), The Daily Telegraph (1), The Express (1), The Western Mail (1) |

| Germany (5) | dpa (17), Deutsche Welle World (5), Die Welt (3), EQS news (1), German news (1) |

| Ireland (4) | Irish Examiner (5), RTE News (5), Irish Independent (3), The Irish Times (1) |

| France (3) | Agence France Presse (27), France 24 (1), RFI (1) |

| Turkey (3) | TRT World (4), Anadolu Agency (2), Hürriyet Daily News (1) |

| Spain (2) | Spanish News (4), EFE (2) |

| Hungary (2) | Hungarian News Digest (3), Budapest Business Journal (1) |

| Luxembourg (1) | Luxembourg Times (3) |

| Denmark (1) | M-Brain Denmark News (1) |

| Uncertain (5) | Automotive Monitor Worldwide (5), Business Monitor Online (3), ICIS (2), China Report Magazine (1), Future News (1) |

| Sentiment | Frequency |

|---|---|

| positive | free (28), strong (14), success (9), great (8), gain (7), confidence (6), generous (6), trust (5), happy (4), enjoy (4), successful (4), positive (4), rescue (4), encourage (3), brilliance (3), win (3), winning (2), justice (2), fun (2), fantastic (2) |

| negative | war (44), punitive (34), threat (31), harm (15), hurt (14), violate (9), negative (9), harming (6), threatening (6), bad (6), abuse (5), disappointment (4), ban (4), damaging (4), rejected (4), dead (3), fearing (3), rejection (3), violating (3), worsen (3) |

| Node Word “China” | Node Word “Beijing” | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Collocates | Frequency | MI | Collocates | Frequency | MI |

| 1 | trade | 115 | 3.13 | Brussels | 28 | 4.68 |

| 2 | imports | 53 | 3.37 | trade | 26 | 3.00 |

| 3 | commerce | 53 | 4.03 | subsidies | 25 | 4.25 |

| 4 | imported | 52 | 4.18 | ministry | 18 | 4.43 |

| 5 | ministry | 45 | 3.73 | commerce | 17 | 4.42 |

| 6 | exports | 40 | 3.68 | talks | 14 | 4.88 |

| 7 | economic | 32 | 3.78 | unfair | 11 | 4.09 |

| 8 | tensions | 31 | 4.35 | tensions | 11 | 4.87 |

| 9 | negotiations | 24 | 3.81 | launched | 11 | 4.85 |

| 10 | cooperation | 24 | 3.81 | investigations | 10 | 5.76 |

| 11 | retaliation | 23 | 4.39 | support | 9 | 4.09 |

| 12 | products | 21 | 3.64 | retaliation | 9 | 5.06 |

| 13 | continue | 20 | 3.96 | move | 9 | 3.64 |

| 14 | unfairly | 19 | 4.34 | war | 8 | 4.14 |

| 15 | association | 19 | 3.62 | unfairly | 8 | 5.12 |

| 16 | pork | 18 | 3.19 | probes | 8 | 5.66 |

| 17 | anti-dumping | 17 | 3.51 | domestic | 8 | 4.16 |

| 18 | minister | 16 | 3.50 | brandy | 8 | 3.71 |

| 19 | war | 15 | 3.02 | anti-subsidy | 8 | 3.34 |

| 20 | response | 15 | 3.67 | accused | 8 | 6.00 |

| China’s Images | Collocates of “China” and “Beijing” |

|---|---|

| the unfair-subsidy provider | unfair(ly), subsidies, anti-subsidy, support, domestic, accused, trade |

| the threatener | retaliation, response, move, launched, anti-dumping, investigations, probes, pork, brandy, products, imported, trade, tensions |

| the negotiator | negotiations, cooperation, talks, continue, trade |

| the defender | commerce, ministry, minister, association |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, J.; Yang, M. Integrating Corpus Linguistics and Text Mining to Analyze European Media Coverage on China–EU Electric Vehicle Dispute. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040196

Fu J, Yang M. Integrating Corpus Linguistics and Text Mining to Analyze European Media Coverage on China–EU Electric Vehicle Dispute. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(4):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040196

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Jinsong, and Min Yang. 2025. "Integrating Corpus Linguistics and Text Mining to Analyze European Media Coverage on China–EU Electric Vehicle Dispute" Journalism and Media 6, no. 4: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040196

APA StyleFu, J., & Yang, M. (2025). Integrating Corpus Linguistics and Text Mining to Analyze European Media Coverage on China–EU Electric Vehicle Dispute. Journalism and Media, 6(4), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040196