Affordances of Wartime Collective Action on Facebook

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Collective Action

3. Social Media and the Theory of Affordances

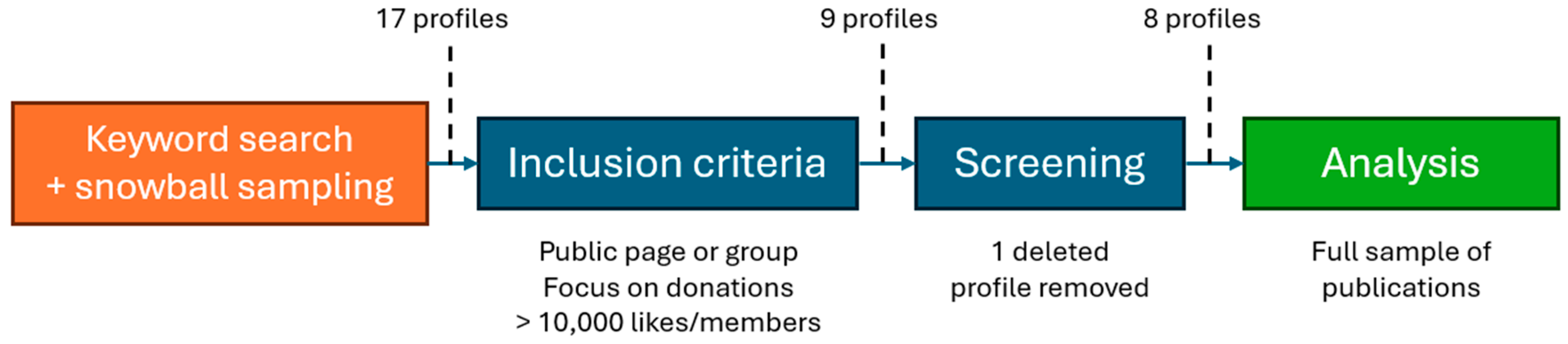

4. Individual and Organisational Profiles

5. Methods

6. Results

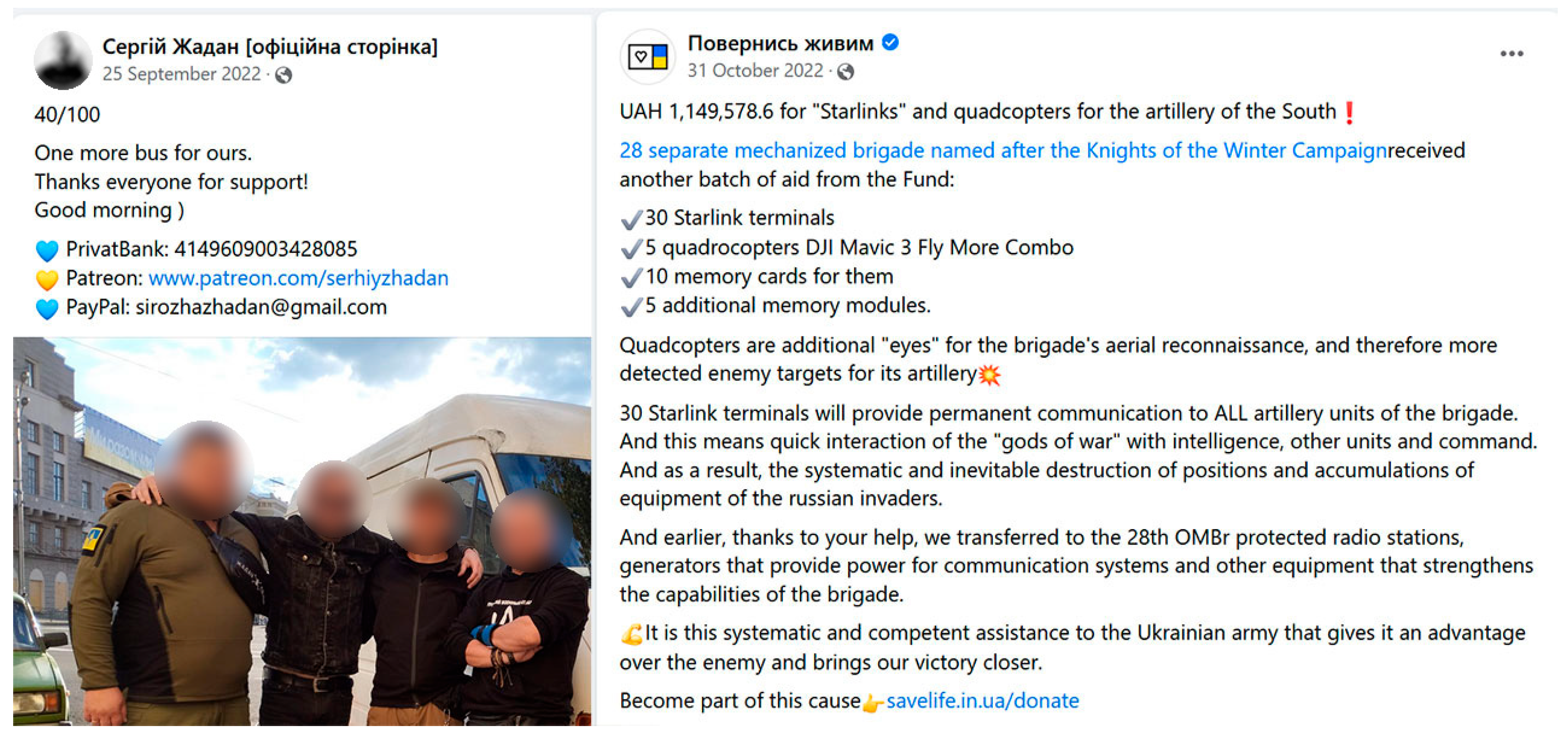

6.1. Post Types: Calls for Action, Reports and Updates

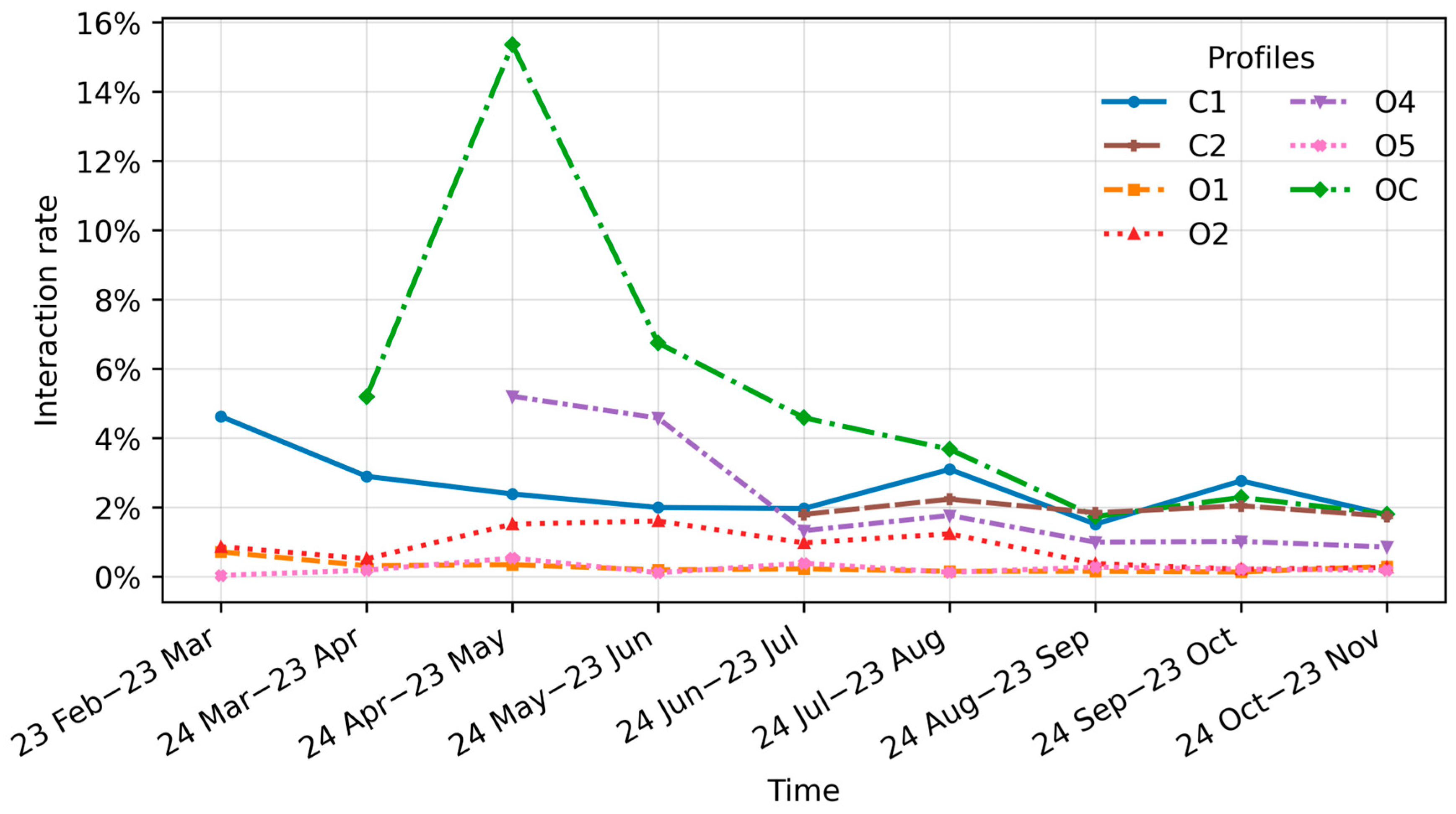

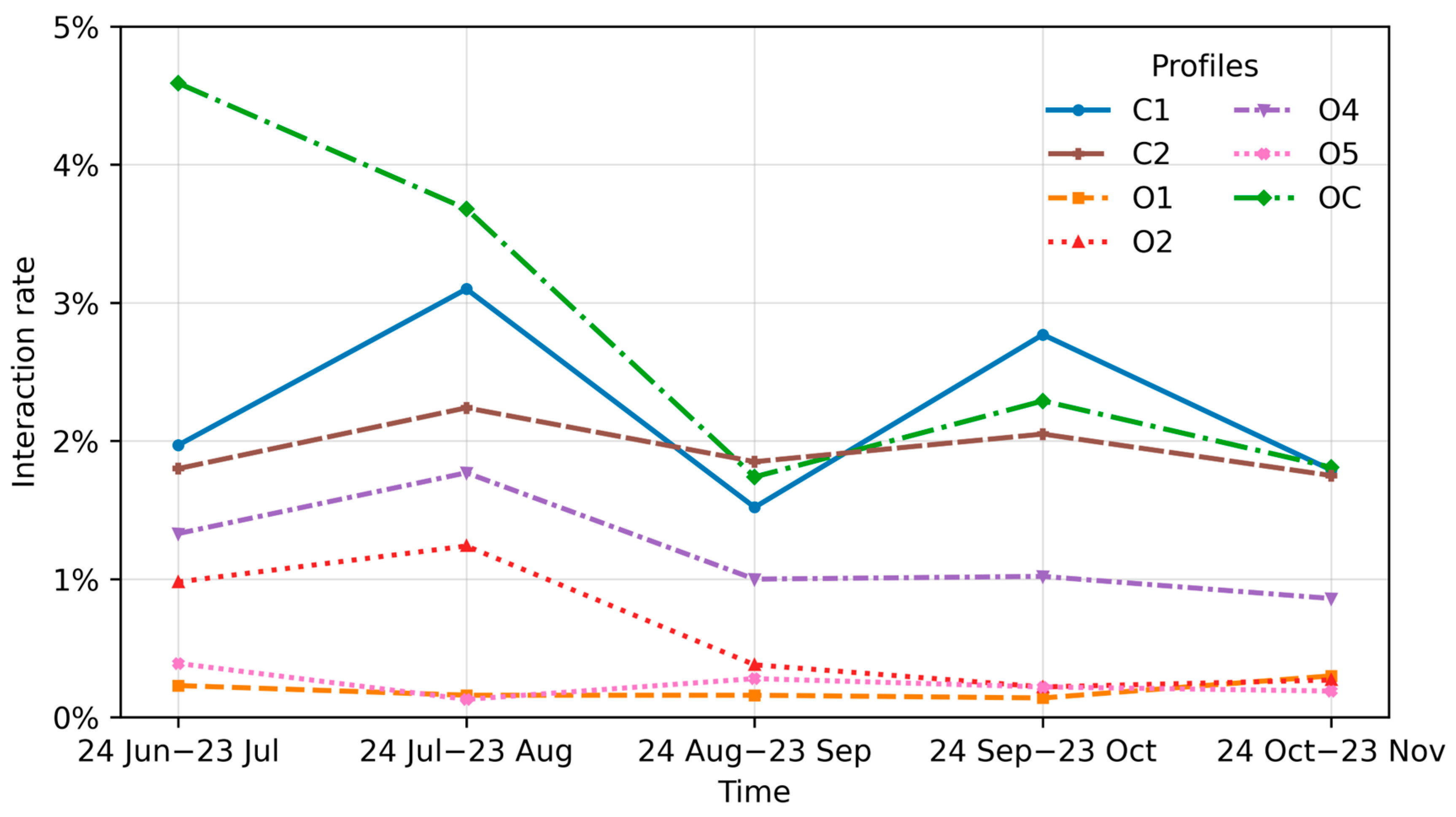

6.2. Audience Engagement and Interaction

6.3. Post Content: Moderation and Algorithms

7. Discussion

- (1)

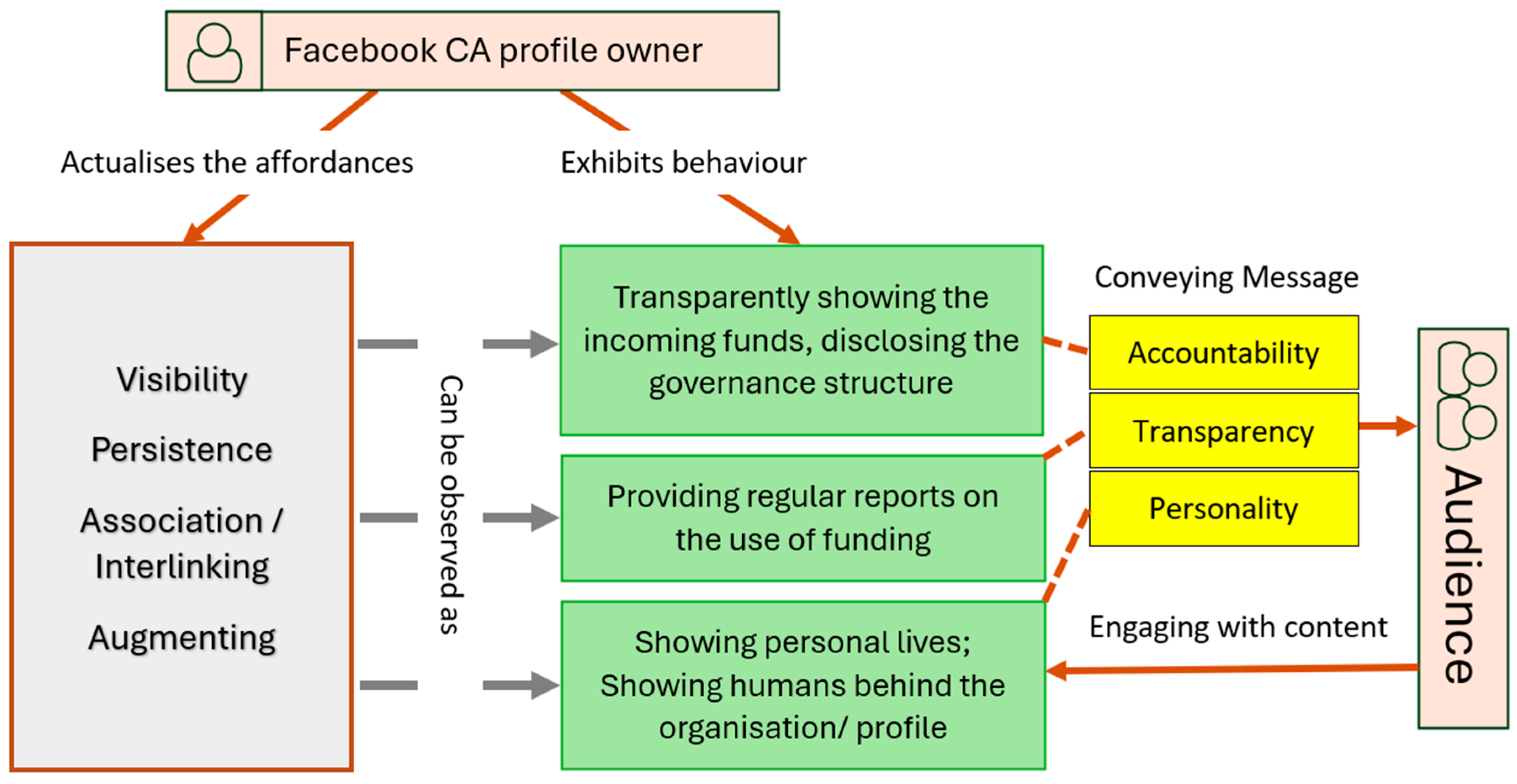

- Different ownership structures lead to distinct affordance strategies. Organisational and celebrity profiles intentionally employ different affordances to achieve trust and participation outcomes: organisations rely on the intentional use of the persistence affordance to generate transparency and legitimacy, whereas individuals draw on the augmenting affordance to convey authenticity and emotional connection. These contrasting strategies illustrate how different actor types navigate the same platform affordances to foster engagement and mobilise collective support. The “hybrid” case (OC) demonstrates that these strategies can also be productively combined.

- (2)

- Engagement as a metric for affordance actualization. Interaction metrics (likes, shares, comments) are not secondary indicators, but evidence of how effectively actors realise visibility and augmenting affordances.

- (3)

- Platform governance shapes affordance use. Algorithmic moderation constrains the actualization of affordances, prompting strategic self-censorship and highlighting the negotiated nature of visibility in wartime context.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Topics and Guiding Questions

- Moderation

- Have you encountered Facebook moderation (e.g., content removal, warnings)? If so, how often? Could you provide an example?

- Have you experienced shadow banning, when Facebook makes a page or specific posts less visible to users?

- To what extent do you consider the possibility of moderation when preparing content for publication?

- Optimisation

- Do you adapt or optimise your content based on how Facebook’s algorithm operates (for example, which posts are more likely to be promoted or hidden)?

- Could you give an example of how you adjust your content accordingly?

- Editing

- Have you used the Edit function to modify already published content (beyond correcting typos or minor errors)?

- If so, how frequently, and could you briefly describe an example?

- Platform Advantages

- In your opinion, what are the main advantages and disadvantages of Facebook as a platform for fundraising, compared to other platforms or fundraising methods?

| 1 | https://www.crowdtangle.com/ (accessed on 25 November 2022). |

| 2 | https://savelife.in.ua/en/reporting-en/ (accessed on 5 December 2022). |

References

- Andén-Papadopoulos, K. (2020). The “image-as-forensic-evidence” economy in the post-2011 Syrian conflict: The power and constraints of contemporary practices of video activism. International Journal of Communication, 14, 5072–5091. [Google Scholar]

- Badran, Y., & Smets, K. (2018). Heterogeneity in alternative media spheres: Oppositional media and the framing of sectarianism in the Syrian conflict. International Journal of Communication, 12, 4229–4247. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, A. (2018). An experimental study of voluntary nonprofit accountability and effects on public trust, reputation, perceived quality, and donation behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(3), 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information Communication and Society, 15(5), 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimber, B., Flanagin, A. J., & Stohl, C. (2005). Reconceptualizing collective action in the contemporary media environment. Communication Theory, 15(4), 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonchek, M. S. (1995, April 23–26). Grassroots in cyberspace: Recruiting members on the internet. [Conference session]. 53rd Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association (pp. 5–8), Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, T. (2012). Want to be on the top? Algorithmic power and the threat of invisibility on Facebook. New Media & Society, 14(7), 1164–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, T., & Helmond, A. (2017). The affordances of social media platforms. In J. Burgess, T. Poell, & A. Marwick (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 233–253). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the internet age. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, D., & Diani, M. (2006). Social movements: An introduction. In International encyclopedia of human geography. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Devito, M. A., Birnholtz, J., & Hancock, J. T. (2017, February 25–March 1). Platforms, people, and perception: Using affordances to understand self-presentation on social media. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) (pp. 740–754), Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G. R. (2004). Journalists’ evaluation of corporate reputations. Corporate Reputation Review, 7(2), 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessens, O. (2013). Celebrity capital: Redefining celebrity using field theory. Theory and Society, 42(5), 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, T., & Kellogg, W. A. (2000). Social translucence: An approach to designing systems that support social processes. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M., & Albu, O. B. (2021). Activists in the dark: Social media algorithms and collective action in two social movement organizations. Organization, 28(1), 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S. K., Pearce, K. E., Vitak, J., & Treem, J. W. (2017). Explicating affordances: A conceptual framework for understanding affordances in communication research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(1), 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farwell, M. M., Shier, M. L., & Handy, F. (2019). Explaining trust in Canadian charities: The influence of public perceptions of accountability, transparency, familiarity and institutional trust. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(4), 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C., & Van Riel, C. (2004). Fame & fortune: How successful companies build winning reputations. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. J. (1977). The concept of affordances. In R. Shaw, & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, acting, and knowing: Toward an ecological psychology (pp. 67–81). Johne Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W., Tinati, R., & Jennings, W. (2018). From Brexit to Trump: Social media’s role in democracy. Computer, 51(1), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harindranath, G., Bernroider, E. W. N., & Kamel, S. H. (2015, May 26–29). Social media and social transformation movements: The role of affordances and platforms. 23rd European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2015) (Paper 73, 0–12), Münster, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchby, I. (2001). Technologies, texts and affordances. Sociology, 35(2), 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioanes, E. (2022, February 26). Ukraine’s resistance is built on the backs of volunteers. Vox. Available online: https://www.vox.com/2022/2/26/22952073/ukraine-civilian-volunteers-kyiv-war-effort (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Kalyvas, S. N., & Kocher, M. A. (2007). How “free” is free riding in civil wars?: Violence, insurgency, and the collective action problem. World Politics, 59(2), 177–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klandermans, B. (2015). Collective action. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 145–150). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krona, M. (2019). ISIS’s media ecology and participatory activism tactics. In M. Krona, & R. Pennington (Eds.), The media world of ISIS (pp. 101–124). Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F. L. F. (2015). Internet, citizen self-mobilisation, and social movement organisations in environmental collective action campaigns: Two Hong Kong cases. Environmental Politics, 24(2), 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-T. (2025). Digital organizers in Hong Kong: The challenges of movement organizing through social media amid democratic backsliding. Social Media + Society, 11(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A. C. (2020). Making ‘my’ problem ‘our’ problem: Warfare as collective action, and the role of leader manipulation. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(2), 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, G., Flow, S., Graeff, E., Project, W. E., Ananny, M., Gaffney, D., Pearce, I., & Boyd, D. (2011). The revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication, 5(2011), 1375–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Lupia, A., & Sin, G. (2003). Which public goods are endangered?: How evolving communication technologies affect the logic of collective action. Public Choice, 117(3/4), 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDuffee Metzger, M., & Tucker, J. A. (2017). Social media and EuroMaidan: A review essay. Slavic Review, 76(1), 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhortykh, M., & Sydorova, M. (2017). Social media and visual framing of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Media, War & Conflict, 10(3), 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetts, H., Hale, S., & John, P. (2014). How social media shapes political participation and the democratic landscape. In M. Graham, & W. H. Dutton (Eds.), Society and the internet (pp. 195–211). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, I. C., Hammer, L. A., Springfield, C. R., & Bonfils, K. A. (2024). Activism in the digital age: The link between social media engagement with black lives matter-relevant content and mental health. Psychological Reports, 127(5), 2220–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozov, E. (2009). The brave new world of Slacktivism. Foreign Policy. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/05/19/the-brave-new-world-of-slacktivism/ (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Nagy, P., & Neff, G. (2015). Imagined affordance: Reconstructing a keyword for communication theory. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, T. E. (2014). Terror.com—IS’s social media warfare in Syria and Iraq. Military Studies Magazine: Contemporary Conflicts, 2, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. A. (1988). The psychology of everyday things. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pecorino, P. (2015). Olson’s logic of collective action at fifty. Public Choice, 162(3–4), 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierri, F., Luceri, L., Jindal, N., & Ferrara, E. (2023, April 30–May 1). Propaganda and misinformation on Facebook and Twitter during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. 15th ACM Web Science Conference 2023 (pp. 65–74), Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolny, J. M. (1993). A status-based model of market competition. American Journal of Sociology, 98(4), 829–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poell, T., Nieborg, D., & van Dijck, J. (2019). Platformisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prier, J. (2020). Commanding the trend. In Information warfare in the age of cyber conflict (pp. 88–113). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzhyn, A. (2014). The use of Facebook and Twitter during the 2013–2014 protests in Ukraine. In A. Rospigliosi, & S. Greener (Eds.), Proceedings of the European Conference on Social Media (pp. 442–449). University of Brighton UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ronzhyn, A., Cardenal, A. S., & Batlle Rubio, A. (2022). Defining affordances in social media research: A literature review. New Media & Society, 25(11), 3165–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijgrok, K. (2017). From the web to the streets: Internet and protests under authoritarian regimes. Democratization, 24(3), 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæbø, Ø., Federici, T., & Braccini, A. M. (2020). Combining social media affordances for organising collective action. Information Systems Journal, 30(4), 699–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D., Saha, B., & Sarkar, U. K. (2016, December 11–14). Bridging the distance: The agencement of complex affordances on social media platforms. 2016 International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2016) (pp. 1–17), Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Skoric, M. M. (2012). What is Slack about Slactivism? Methodological and Conceptual Issues in Cyber Activism Research, 77(7), 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaeman, D. (2017, June 24–25). Charitable fundraising: Gaining donors’ trust on online platforms. 11th China Summer Workshop on Information Management (CSWIM 2017) (pp. 469–474), Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Treem, J. W., & Leonardi, P. M. (2013). Social media use in organizations: Exploring the affordances of visibility, editability, persistence, and association. Annals of the International Communication Association, 36(1), 143–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaast, E., Safadi, H., Lapointe, L., & Negoita, B. (2017). Social media affordances for connective action: An examination of microblogging use during the Gulf of Mexico oil spill. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 41(4), 1179–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengattil, M., & Culliford, E. (2022). Facebook allows war posts urging violence against Russian invaders. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/exclusive-facebook-instagram-temporarily-allow-calls-violence-against-russians-2022-03-10/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Wood, E. J. (2003). Insurgent collective action and civil war in El Salvador. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worschech, S. (2017). New civic activism in Ukraine: Building society from scratch? Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal, 3, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. C. (2009). The next generation of collective action research. Journal of Social Issues, 65(4), 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, V., Aal, K., Abu Kteish, I., Atam, M., Schubert, K., Rohde, M., Yerousis, G. P., & Randall, D. (2013, April 27–May 3). Fighting against the wall: Social media use by political activists in a Palestinian village. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1979–1988), Paris, France. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W., & Čačija, L. N. (2022). Online social network fundraising: Threats and potentialities. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, e1782, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J., Jindal, N., Pierri, F., & Luceri, L. (2023). Online networks of support in distressed environments: Solidarity and mobilization during the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. arXiv, arXiv:2304.04327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., & Yu, A. (2016). Affordances of social media in collective action: The case of free lunch for children in China. Information Systems Journal, 26(3), 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., & Ye, S. (2021). Fundraising in the digital era: Legitimacy, social network, and political ties matter in China. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32(2), 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Facebook Affordance | How to Measure | Expected Variance Between Profiles |

|---|---|---|

| General Facebook Affordances (Treem & Leonardi, 2013) | ||

| Visibility | Number of posts/post types | High |

| Post engagement | ||

| Persistence | Number of deleted posts | Low |

| Age of profile | ||

| Association/Interlinking | Use of tagging and post sharing functions | High |

| Use of hashtags | ||

| Editability | Frequency of editing published posts | Low |

| CA-Specific Facebook Affordances (Etter & Albu, 2021) | ||

| Assembling | Cannot be measured from public data | High |

| Augmenting | Post engagement | High |

| Use of hashtags | ||

| Cross-platform engagement | ||

| Code | Facebook Profile | Type | Followers |

|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | Come Back Alive | Organisation | 3.5 M |

| C1 | Serhiy Zhadan 1 | Celebrity | 162,362 |

| O2 | Razom for Ukraine | Organisation | 48,803 |

| OC | Fond Serhiya Prytuly | Organisation/Celebrity | 36,422 |

| O3 | Armiya SOS [group] | Organisation | 33,467 |

| O4 | Hospitallers Paramedics | Organisation | 32,820 |

| O5 | Pidtrymai Armiyu Ukrayiny | Organisation | 11,987 |

| C2 | Andriy Lyubka | Celebrity | 11,442 |

| Profile | O1 | C1 | O2 | OC | O4 | O5 | C2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calls | 437 | 70 | 183 | 77 | 308 | 26 | 26 | 1128 |

| Reports | 378 | 155 | 130 | 196 | 129 | 21 | 94 | 1103 |

| Ratio (R/C) | 0.86 | 2.21 | 0.71 | 2.55 | 0.42 | 0.81 | 3.61 | 0.98 |

| Profile | O1 | C1 | O2 | OC | O4 | O5 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M length | 157.55 | 70.3 | 153.8 | 111.1 | 110.4 | 182.8 | 6.9 |

| Std. Dev | 67.1 | 49.6 | 108.9 | 73.8 | 127 | 79.0 | 10.4 |

| Facebook Affordance | Actualisation of Affordance | |

|---|---|---|

| Organisational Profiles | Celebrity Profiles | |

| Visibility | Very high number of reports to calls to action. | High number of reports to calls to action. |

| Low post engagement per user | High post engagement per user | |

| Post content optimisation | Post content optimisation | |

| Persistence | Use of content persistence to boost transparency and show performance | Use of persistence to boost authenticity and show transparency |

| Association/Interlinking | Use of post sharing functions to attract and promote donors | Use of tagging |

| Use of hashtags to link the reports | Greater personal engagement with users | |

| Editability | Low number of edited posts | Low number of edited posts |

| Augmenting | More frequent use of additional functions (e.g., live videos) | Use of emotion-evoking imagery |

| Use of cross-platform engagement | Publication of personal content to boost engagement | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ronzhyn, A.; Batlle Rubio, A.; Cardenal, A.S. Affordances of Wartime Collective Action on Facebook. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040194

Ronzhyn A, Batlle Rubio A, Cardenal AS. Affordances of Wartime Collective Action on Facebook. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(4):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040194

Chicago/Turabian StyleRonzhyn, Alexander, Albert Batlle Rubio, and Ana Sofia Cardenal. 2025. "Affordances of Wartime Collective Action on Facebook" Journalism and Media 6, no. 4: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040194

APA StyleRonzhyn, A., Batlle Rubio, A., & Cardenal, A. S. (2025). Affordances of Wartime Collective Action on Facebook. Journalism and Media, 6(4), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040194