Digital Media Discourse and the Secularization of Germany: A Textual Analysis of News Reporting in 2020–2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Digital Penetration and Belief Transformation: The Historical Context of Secularization in Germany

1.2. Research Significance: Bridging the Gap in Studies on the Interaction Between Digital Media and Secularization

1.3. Core Research Questions: Interactive Charateristics Between Digital Media Discourse and the Secularization Process

1.3.1. Evolution of Discursive Features

1.3.2. Temporal Correlation

1.3.3. Framing Effects and Mechanisms

1.4. Key Concepts

2. Literature and Analytical Framework

2.1. Evolution of Secularization Theory: From Linear Disenchantment to Contextualized Interaction

2.2. Digital Media and the Reconfiguration of Religious Discourse: Power Structures and Practice Transformation

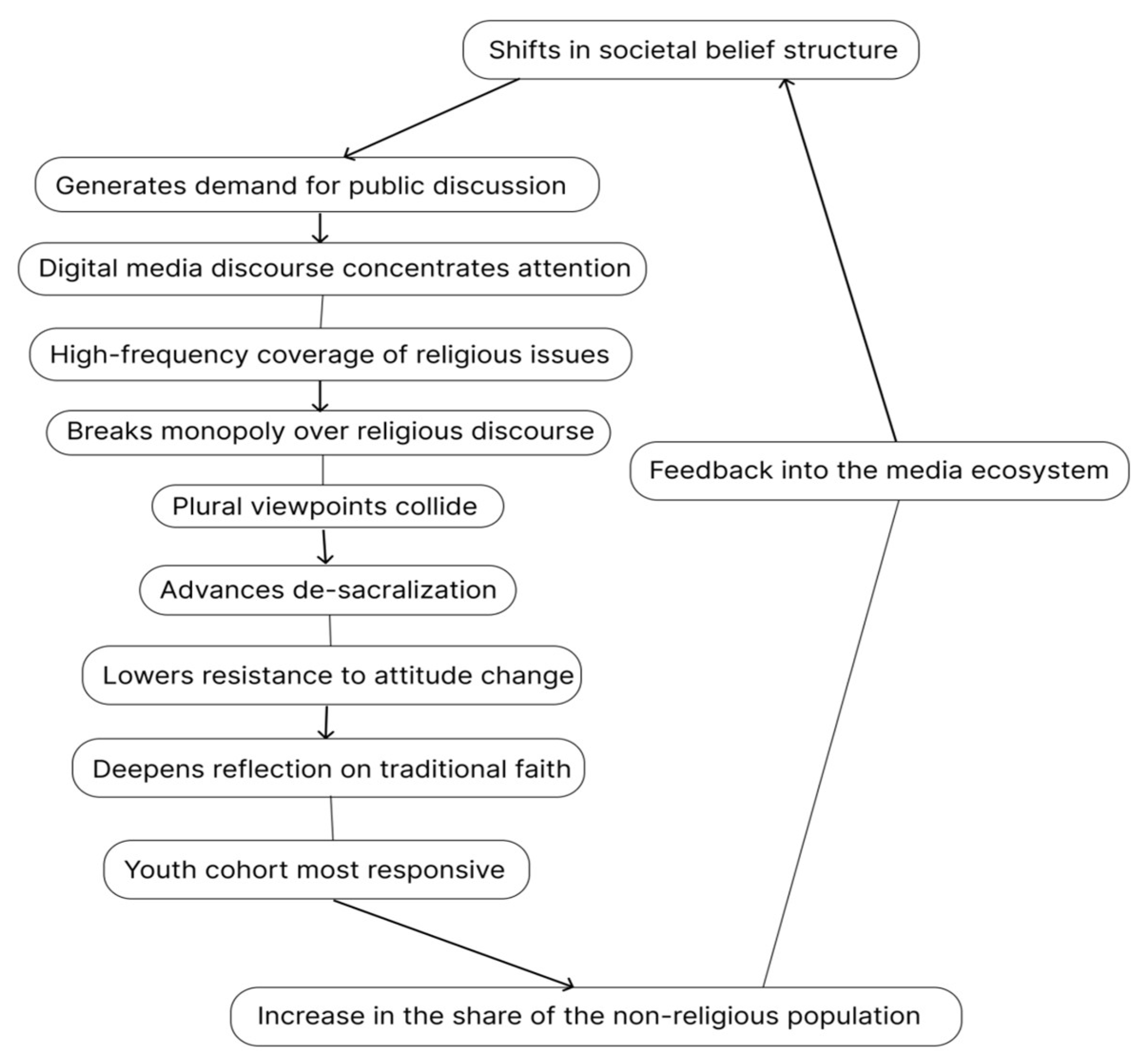

2.3. A Spiral Mechanism of Bidirectional Influence: Dynamic Entanglement of Digital Media and Secularization

2.4. Digital Growth and the Causality Question

2.5. Subsection

2.6. Summary

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Foundations: Selection and Acquisition Strategy of Mainstream Media Texts

3.1.1. Data Types and Scope

3.1.2. Data Collection Tools and Procedures

3.2. Data Preprocessing: From Raw Texts to Analytical Corpus

3.3. Multidimensional Analytical Framework: Decoding the Link Between Digital Media Discourse and Secularization

3.3.1. Text Analysis

3.3.2. Statistical and Spatiotemporal Correlation Tests

3.4. Reliability and Validity Assurance: Cross-Verification with Multiple Tools

4. Results

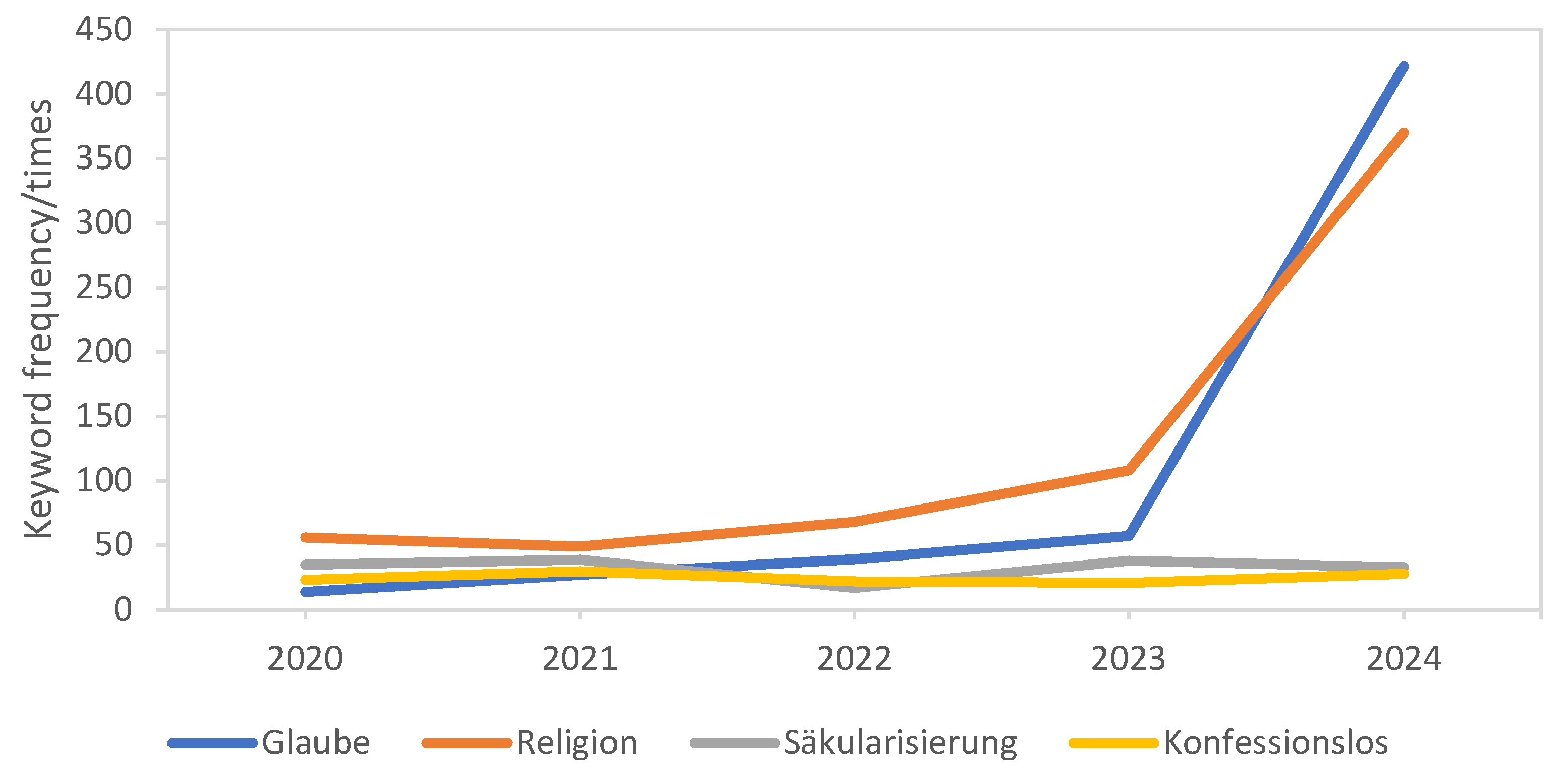

4.1. Keyword Frequency Patterns: Media Attention to Religious Topics

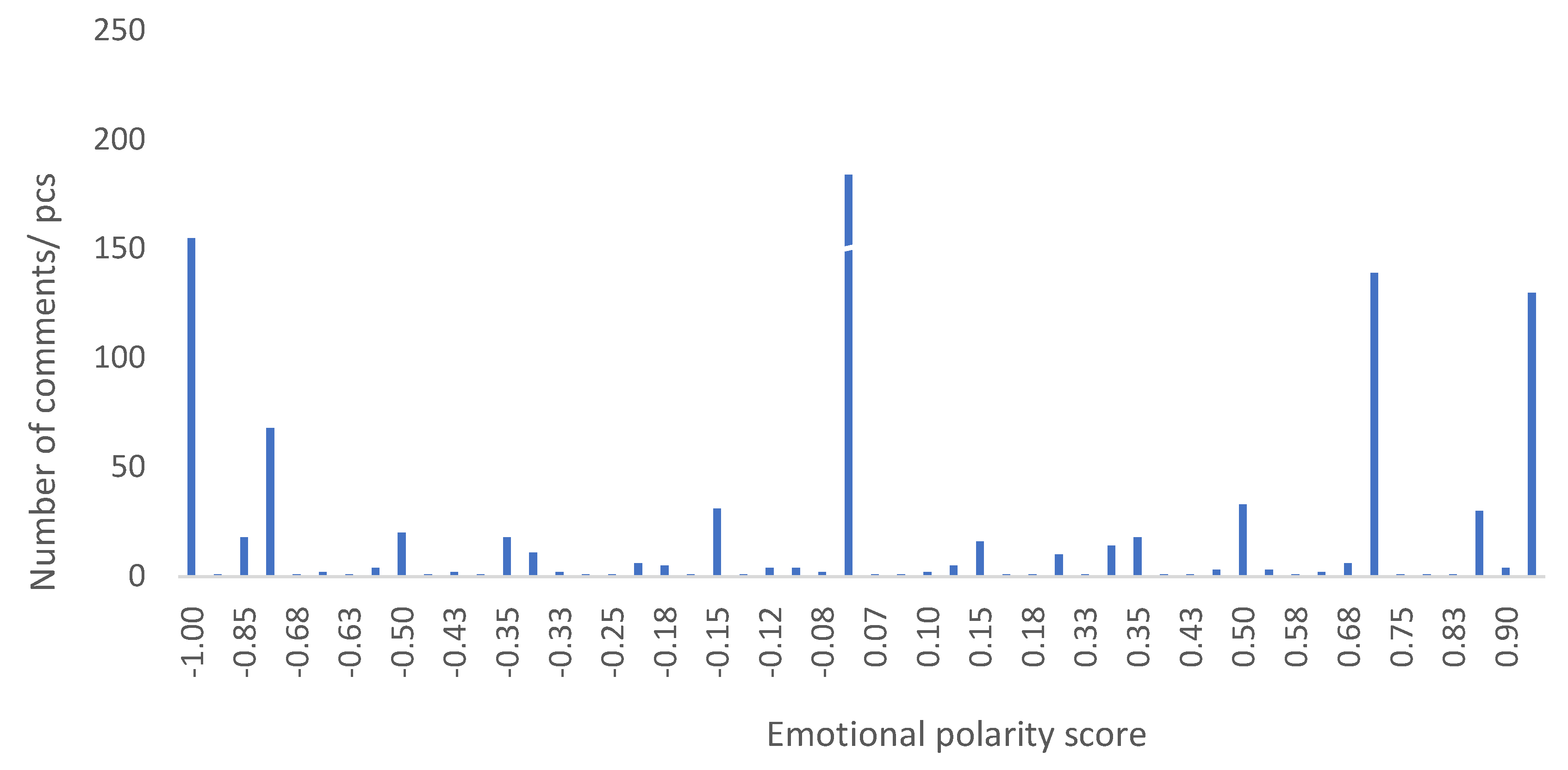

4.2. Sentiment Topography: A Drift Toward Moderation

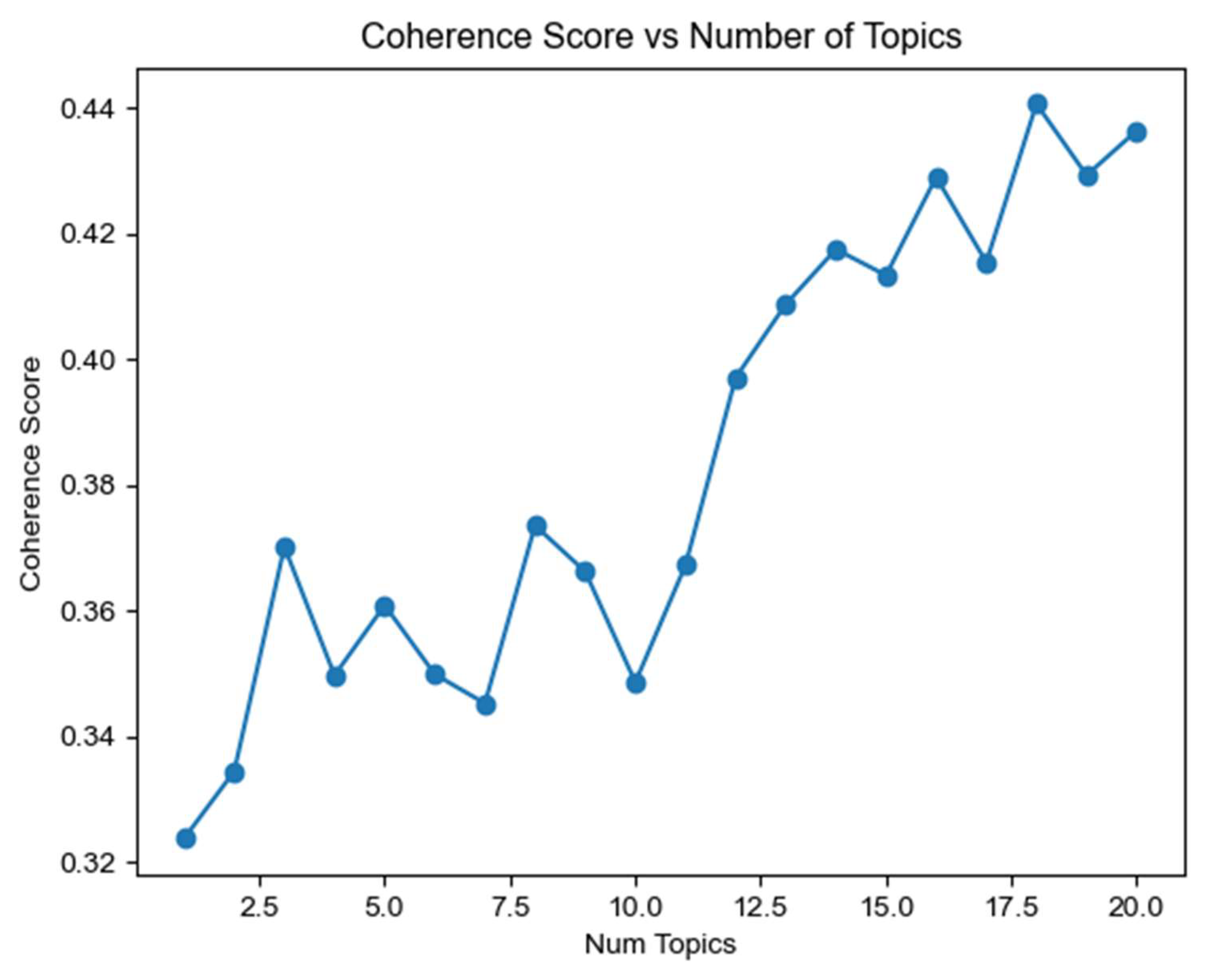

4.3. Topics and Frames: Narrative Rotation from “Sacred Authority” to “Secular Function”

4.4. Temporal Interaction Evidence: Media Leads the Secularization Curve

5. Discussion

5.1. Media Discourse as Both Driver and Mirror of Secularization

5.2. Digital Supplements to Secularization and Mediatization Theory

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions: Extending Breadth and Deepening Mechanisms

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, P. (2015). One exceptional figure stood out. London Review of Books, 37(15), 19. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, E., & Yildiz, E. (2024). Muslim religiosity in the digital transformation: How young people deal with images of islam in the media (1st ed.). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, R. (2017). Peter berger on modernization and modernity: An unvarnished overview (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bonikowski, B., & Nelson, L. K. (2022). From ends to means: The promise of computational text analysis for theoretically driven sociological research. Sociological Methods & Research, 51(4), 1469–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, G., Leustean, L. N., & Davie, G. (2022). Religion, secularity, and secularization in Europe (pp. 268–284). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, G., Woodhead, L., Catto, R., Woodhead, L., Kawanami, H., & Partridge, C. (Eds.). (2016). Secularism and secularization (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dhima, K., & Golder, M. (2021). Secularization theory and religion. Politics and Religion, 14(1), 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diller, C., & Gareis, P. (2020). Secularization, religious denominations, and differences in regional characteristics: The state of research and a regional statistical investigation for Germany. Religions, 11(12), 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbelaere, K. (2017). Testing secularization theory in comparative perspective. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society, 20(2), 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euchner, E.-M. (2019). Morality politics in a secular age: Strategic parties and divided governments in Europe (1st ed.). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, W. D., Abroms, L. C., Broniatowski, D., Napolitano, M. A., Arnold, J., Ichimiya, M., & Agha, S. (2022). Digital media for behavior change: Review of an emerging field of study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evolvi, G. (2018). Blogging my religion: Secular, muslim, and catholic media spaces in Europe. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evolvi, G. (2021). Religion, new media, and digital culture. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, F. (2020). (What is left of) secularization? Debate on Jörg Stolz’s article on secularization theories in the 21st century: Ideas, evidence, and problems. Social Compass, 67(2), 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, M. (Ed.). (2023). The role of media in creating communities of religious belief and identity. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, P. S., & Altınordu, A. (2008). After secularization? Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, D., Słomka, J., & Cieslik, E. (2024). Digital, hybrid and traditional media consumption and religious reflection. Central European Journal of Communication, 17(37), 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, M., Skirbekk, V., & Stonawski, M. (2020). The religiously unaffiliated in germany, 1949–2013: Contrasting patterns of social change in east and west. Sociological Quarterly, 61(2), 254–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelm, T. (2018). Peter L. Berger and the sociology of religion: 50 years after the Sacred Canopy (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Höpflinger, F. (2012). Grossvaterschaft: Entwicklungen, engagements und beziehungsmuster. In H. Walter, & A. Eickhorst (Eds.), Das väter-handbuch: Theorie, forschung, praxis. Psychosozial-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, I. (2014). Secularization: The birth of a modern combat concept. Modern Intellectual History, 12(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejska, M., & Neumaier, A. (2017). Between individualisation and tradition: Transforming religious authority on German and Polish Christian online discussion forums. Religion, 47(2), 228–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körs, A. (Ed.). (2025). Interreligious dialogue and relations in Germany from a multilevel governance perspective. Religion in Motion, 6, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Löffler, W. (2023). Secularization and other master-theories on religion and society: A European perspective (pp. 27–38). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. [Google Scholar]

- Lundby, K., & Evolvi, G. (2022). Theoretical frameworks for approaching religion and new media. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, A. (2024). Discovering the child? Individualization processes of catholic religious education in the horizon of secularization since 1900. Verbum Vitae: Półrocznik Biblijno-Teologiczny, 42(1), 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D., Waldherr, A., Miltner, P., Wiedemann, G., Niekler, A., Keinert, A., Pfetsch, B., Heyer, G., Reber, U., Häussler, T., Schmid-Petri, H., & Adam, S. (2018). Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: Toward a valid and reliable methodology. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(2–3), 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. (2017). On secularization: Towards a revised general theory (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mattes, A., Haselbacher, M., Limacher, K., & Novak, C. (2025). Religion and politics of belonging in digital times: Youth religiosity in focus. Frontiers in Political Science, 6, 1476762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, A. S., Stewart, S. A., Halley, M. C., Nelson, L. K., & Linos, E. (2023). Formally comparing topic models and human-generated qualitative coding of physician mothers’ experiences of workplace discrimination. Big Data & Society, 10(1), 20539517221149106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, K. (2019). Islamophobia in reactionary news: Radicalizing Christianity in the United States. Open Library of Humanities, 5(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J., & Friemel, T. N. (2024). Dynamics of digital media use in religious communities—A theoretical model. Religions, 15(7), 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, O., Pollack, D., Pickel, G., Müller, O., Pollack, D., & Pickel, G. (2012). The religious landscape in Germany: Secularizing west—Secularized east (1st ed., pp. 95–120). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, L. K., Burk, D., Knudsen, M., & McCall, L. (2021). The future of coding: A comparison of hand-coding and three types of computer-assisted text analysis methods. Sociological Methods & Research, 50(1), 202–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, G., & Montalbano, K. (2023). Covering religion: Field insurgency in United States religion reporting. Journalism, 24(6), 1193–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, G. P. (2023). Digital hate: Normalization in management of online hostility. In The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies (pp. 406–416). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pickel, G., Pickel, S., Schmidt, P., & Heller, A. (2024). Religiosity, non-denominationalism, and their political consequences in East and West Germany after the upheaval of 1989 (1st ed., pp. 153–178). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, D. (2015). Varieties of secularization theories and their indispensable core. The Germanic Review, 90(1), 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, D., & Rosta, G. (2017). Religion and modernity: An international comparison. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, A., Behrens, K., & Grötsch, F. (2017). Religion in European constitutions—Cases of different secularities. European Societies, 19(5), 551–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. (2001). The problem of essentialism. In Gender, Peace and Conflict (pp. 32–46). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz, D. S., & Taylor, M. A. (2024). Mapping texts: Computational text analysis for the social sciences. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, J. (2020). Secularization theories in the twenty-first century: Ideas, evidence, and problems. Presidential address. Social Compass, 67(2), 282–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, J., & Könemann, J. (2016). A theory of religious-secular competition. In J. Stolz, J. Könemann, M. S. Purdie, T. Englberger, & M. Krüggeler (Eds.), (Un)Believing in modern society (1st ed., p. 310). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz, J., Pollack, D., & De Graaf, N. D. (2020). Can the state accelerate the secular transition? Secularization in East and West Germany as a natural experiment. European Sociological Review, 36(4), 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiefensee, E. (Ed.). (2017). More than just de-christianization: Christian mission in face of religious indifference in East Germany. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tiefensee, E. (2024). Christianity in the secular context of East. The faith and beliefs of “Nonbelievers”. The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- Weisse, W. (2016). Religious pluralization and secularization in continental Europe, with focus on France and Germany. Society, 53(1), 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegandt, K., Joas, H., Skinner, A., & Verantwortung, F. F. (2022). Secularization and the world religions. Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, T. L. (2023). A dark cloud of witnesses: The mediatization of evangelical parishioners by religious digital media content creators and its impact on traditional pastoral authority [Ph.D. Thesis, Regent University]. [Google Scholar]

- Zaid, B., Fedtke, J., Shin, D. D., El Kadoussi, A., & Ibahrine, M. (2022). Digital islam and muslim millennials: How social media influencers reimagine religious authority and islamic practices. Religions, 13(4), 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. (2025). The digital age of religious communication: The shaping and challenges of religious beliefs through social media. Studies on Religion and Philosophy, 1(1), 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulehner, P. (2024). Western Europe: Secularisation light. Journal of the Belarusian State University. Sociology, 2, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic Category | Characteristic Tokens (Top Words) |

|---|---|

| Faith in wartime Germany through digital-media coverage | saints; large; attempt; believe; propose; Richard; war; entire; we; speak |

| Media portrayals of church and public doubt in Germany | believe; church; people; why; always; Germans; show; become; dialogue |

| Media presentation of Germans’ questions about faith and dialogue | faith; dialogue; for this; why; more; people; United States; often; country; data |

| Links between German history, presidents and faith (digital perspective) | believe; Germany; people; president; often; history; France; who; for this; more |

| Media focus on contemporary Berliners’ attitudes toward church and faith | people; Germany; why; new; have; church; faith; say; Berlin; today |

| Media images of German churches, faith and diverse groups | church; faith; more; people; United States; Muslims; why; Catholicism; new |

| Trajectory of German faith in the Trump era (media attention) | faith; nation; Trump; future; new; show; EU; many; always; self |

| German faith changes in the context of the U.S. presidency (media depiction) | believe; United States; president; people; year; is; many; among; two; good |

| Germans’ faith life within the world order (media writing) | say; world; people; life; believe; more; is; see; Islam; ongoing |

| Media construction of the chancellor’s image and everyday life | move; chancellor; people; more; many; is; world; think; stop; ahead |

| Ongoing media tracking of perplexities in Germans’ faith life | people; life; say; Germany; why; church; long-term; visit; have; is |

| Media analyses of Muslim faith in Germany and questions about church roles | people; believe; many; life; always; Germans; participate; why; more; today |

| Children’s faith and church interactions in Germany (media attention) | believe; many; church; why; Muslims; more; who; always; people; role |

| Long-term shifts in German faith under U.S. presidential influence (media records) | children; faith; people; because; have; many people; Germany; church; think; Catholicism |

| Media interpretations of religious events and government roles in Germany | more; faith; president; year; many; people; today; United States; become; still |

| Authors’ depictions of faith and development in Germany (media presentation) | believe; situation; believe; religion; many; government; more; show; Europe; work |

| Year-end reviews of church and public faith in Germany (media overviews) | believe; more; people; Germany; have; many; author; year; party; few |

| New media developments on public faith and church activities in Germany | believe; church; year; people; more; many; say; Germany; have; church |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Song, W. Digital Media Discourse and the Secularization of Germany: A Textual Analysis of News Reporting in 2020–2024. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040186

Zhang J, Song W. Digital Media Discourse and the Secularization of Germany: A Textual Analysis of News Reporting in 2020–2024. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(4):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040186

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jing, and Wenlong Song. 2025. "Digital Media Discourse and the Secularization of Germany: A Textual Analysis of News Reporting in 2020–2024" Journalism and Media 6, no. 4: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040186

APA StyleZhang, J., & Song, W. (2025). Digital Media Discourse and the Secularization of Germany: A Textual Analysis of News Reporting in 2020–2024. Journalism and Media, 6(4), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6040186