Examining Crisis Communication in Geopolitical Conflicts: The Micro-Influencer Impact Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Model Development

2.1. The Evolution of Crisis Communication Theory

2.2. Social Influence and Micro-Influencer Characteristics

2.3. Message Framing and Audience Dynamics

2.4. Crisis Context and Temporal Dynamics

2.5. Trust Dynamics and Network Effects

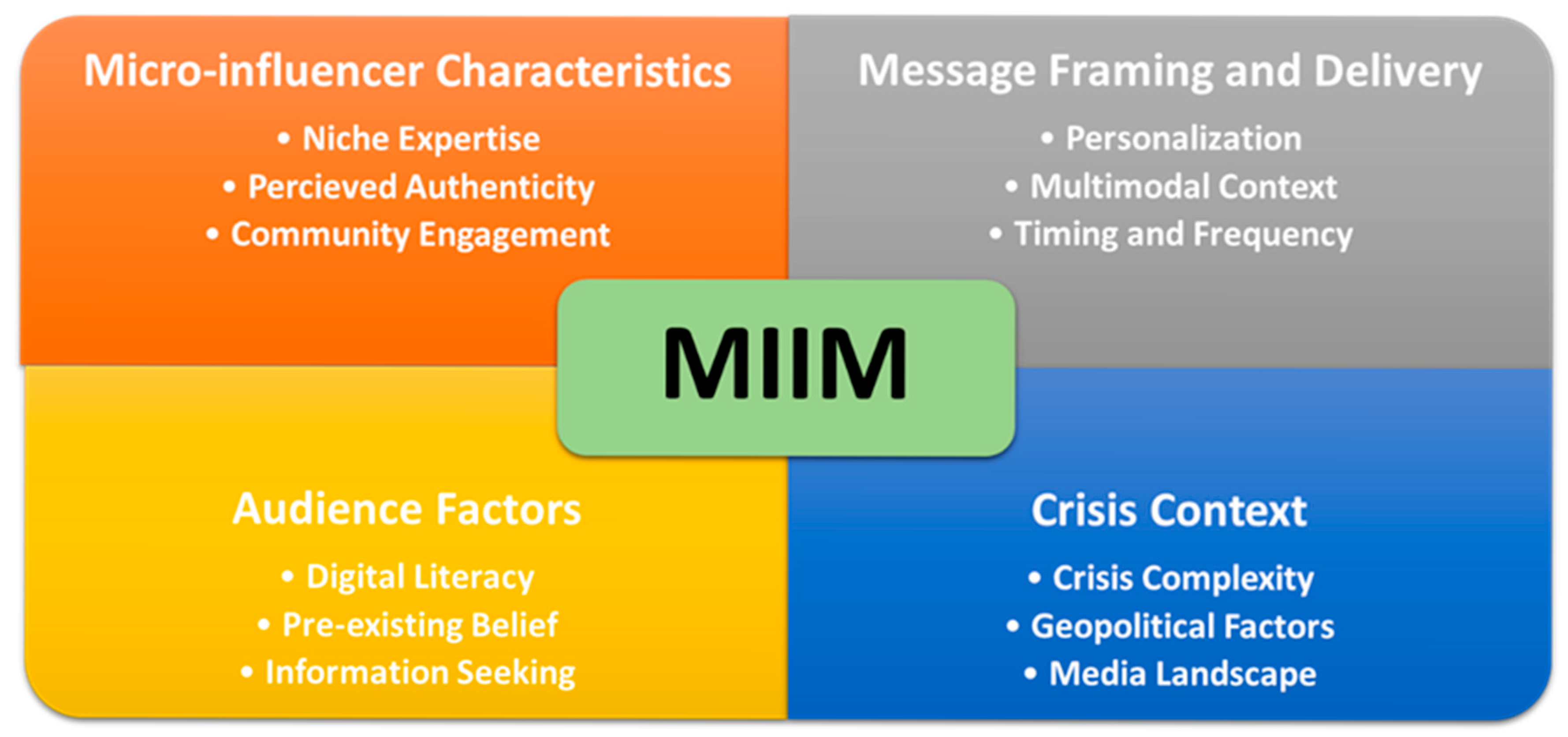

2.6. The Integrated MIIM Framework

3. Cross-Conflict Evidence for MIIM Generalizability

3.1. Ukraine Conflict Micro-Influencers as Crisis Communication Pioneers

3.2. Sudan–Ethiopia Conflicts Reveal Micro-Influencer Adaptation Under Constraints

3.3. Cross-Conflict Patterns Demonstrate MIIM Universality

3.4. Message Framing Strategies Reveal Sophisticated Audience Adaptation

3.5. Community Engagement Demonstrates Universal Network Effects

3.6. Crisis Context Effects Show Universal Adaptation Patterns

3.7. Impact Evidence Validates Micro-Influencer Influence Across Contexts

4. Implications

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIIM | Micro-influencer impact model |

| NCCT | Networked crisis communication theory |

References

- Abidin, C. (2015). Communicative❤ intimacies: Influencers and perceived interconnectedness. Ada: A journal of gender, new media, and technology, 8, 1–16. Available online: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/a18cd997-772b-42f9-acb3-096dadfa2eae/content (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Abidin, C., & Thompson, E. C. (2012). BuyMyLife.com: Cyberfemininities and commercial intimacy in blogshops. Women’s Studies International Forum, 35(6), 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAhmad, H. (2024). A propagative paradigm: Mastering information influence. In Stabilizing authoritarianism: The political echo in Pan-Arab satellite TV news media (pp. 125–162). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Audrezet, A., de Kerviler, G., & Guidry Moulard, J. (2020). Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. Journal of Business Research, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., Brown, T. W., Bumpus, J. P., Chen, H., Hunzaker, M. F., Lee, J., Mann, M., Merhout, F., & Volfovsky, A. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 115(37), 9216–9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansinath, B. (2022, March 11). TikTokking from a bomb shelter. The Cut. Available online: https://www.thecut.com/2022/03/tiktoking-from-a-bomb-shelter.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Boman, C. D., Schneider, E. J., & Akin, H. (2024). Examining the mediating effects of sincerity and credibility in crisis communication strategies. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 29(4), 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkovich, D. J., & Breese, J. L. (2016). Social media implosion: Context collapse! Issues in Information Systems, 17(4), 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braddock, K., & Dillard, J. P. (2023). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 83(4), 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L. E. (2021). Cultural narrative identities and the entanglement of value systems. In Differences, similarities and meanings: Semiotic investigations of contemporary communication phenomena (Vol. 30, pp. 121–146). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, A., & Highfield, T. (2015). Is Habermas on Twitter?: Social media and the public sphere. In The Routledge companion to social media and politics (pp. 56–73). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Zhang, Y., Cai, H., Liu, L., Liao, M., & Fang, J. (2024). A comprehensive overview of micro-influencer marketing: Decoding the current landscape, impacts, and trends. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y., Wang, Y., & Kong, Y. (2022). The state of social-mediated crisis communication research through the lens of global scholars: An updated assessment. Public Relations Review, 48(2), 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R., & Casais, B. (2023). Micro, macro and mega-influencers on instagram: The power of persuasion via the parasocial relationship. Journal of Business Research, 158, 113708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divon, T., & Eriksson Krutrök, M. (2025). The rise of war influencers: Creators, platforms, and the visibility of conflict zones. Platforms & Society, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebulueme, J., & Vijayakumar, V. (2024). Authenticity and influence: Interactions between social media micro-influencers and generation z on instagram. Critique, 14(4), 568–586. [Google Scholar]

- Elhosary, M. (2024). When and why do Arabs verify? Predicting online news verification intention during the 2023 Gaza war. AUC Knowledge Fountain. Available online: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/2248 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Eriksson, M. (2024). Living a ‘Digital life’and ready to cope with crises? Highlighting young adults’ conceptions of crisis and emergency preparedness. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 32(1), e12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fana Broadcasting Corporate. (2025, March 29). New campaign launched to mobilize $3 million from Ethiopian diaspora for GERD. Available online: https://www.fanamc.com/english/new-campaign-launched-to-mobilize-3-million-from-ethiopian-diaspora-for-gerd/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Fasinu, E. S., Olaniyan, B. J. T., & Afolaranmi, A. O. (2024). Digital diplomacy in the age of social media: Challenges and opportunities for crisis communication. African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research, 7(3), 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feezell, J. T. (2020). Agenda setting through social media: The importance of incidental news exposure and social filtering in the digital era. Political Research Quarterly, 71(2), 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, D. (2024). Digital diplomacy: How social media influences international relations in the 21st century. International Journal of Unique and New Updates, 6(1), 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2022). Rhetorical arena theory: Revisited and expanded. In The handbook of crisis communication (pp. 169–181). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Frąckowiak, M. (2025). Photography as Social Transformation: How the Idea of Change Helps Us to Understand the Taking, Sharing, and Debating of Images. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardone, I., & Stremlau, N. (2011). Digital media, conflict, and Diasporas in the Horn of Africa. Open Society Foundations. [Google Scholar]

- Gammarano, I. D. J. L. P., Dholakia, N., Arruda Filho, E. J. M., & Dholakia, R. R. (2024). Beyond influence: Unraveling the complex tapestry of digital influencer dynamics in hyperconnected cultures. European Journal of Marketing, 59(1), 21–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. (2020). Content moderation, AI, and the question of scale. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 2053951720943234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Guidry, J. P. D., Meganck, S. L., Lovari, A., Messner, M., Medina-Messner, V., Sherman, S., & Adams, J. (2020). Tweeting about #Diseases: Communicating global health crises on Twitter. Journal of Health Communication, 28(2), 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Guntrum, L. G. (2024). Keyboard fighters: The use of ICTs by activists in times of military coup in Myanmar. In proceedings of the CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. Association for Computing Machinery. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3613904.3642279 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Gupta, S., Singh, A. K., Buduru, A. B., & Kumaraguru, P. (2020). Hashtags are (not) judgemental: The untold story of Lok Sabha elections 2019. In 2020 IEEE sixth international conference on multimedia big data (BigMM) (pp. 216–220). IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Hakobyan, A. (2021). Memes as a tool for digital resistance in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Journal of Digital Conflict Studies, 5(2), 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan, Y. (2024). Wartime Influencers: Palestinian citizen journalism on Instagram during the war on Gaza 2023–2024 [Master’s thesis, Utrecht University]. [Google Scholar]

- Hameleers, M., Tulin, M., de Vreese, C. H., Aalberg, T., van Aelst, P., Cardenal, A. S., Corbu, N., Erkel, P. V., Esser, F., Gehle, L., Halagiera, D., Hopmann, D., Koc-Michalska, K., Matthes, J., Meltzer, C., Mihelj, S., Schemer, C., Sheafer, T., Splendore, S., … Zoizner, A. (2024). Mistakenly misinformed or intentionally deceived? Mis-and disinformation perceptions on the Russian war in Ukraine among citizens in 19 countries. European Journal of Political Research, 63(4), 1642–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L. (2024). Personal Attributes of Micro-Influencers. In Unpacking micro-influence within the Australian creative sectors: A theoretical framework for understanding the skills, knowledge, and capabilities of micro-influencers (pp. 95–121). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A., & Lanfranchi, G. (2023). Kleptocracy versus democracy: How security-business networks hold hostage Sudan’s private sector and the democratic transition. Clingendael Institute. Available online: https://www.clingendael.org/publication/kleptocracy-versus-democracy (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Horton, D., & Wohl, R. (1956). Mass communication and parasocial interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, J. B., Spialek, M. L., Cox, J., Greenwood, M. M., & First, J. (2015). The centrality of communication and media in fostering community resilience: A framework for assessment and intervention. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høiby, M., & Ottosen, R. (2017). Journalism under pressure in conflict zones: A study of journalists and editors in seven countries. Media, War & Conflict, 10(2), 207–224. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1750635217728092 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2021). The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising: The Review of Marketing Communications, 40(3), 327–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L. Y. (2023). Social media, disinformation, and democracy: How different types of social media usage affect democracy cross-nationally. Democratization, 30(6), 1040–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influencer Marketing Hub. (2024). Influencer marketing report May 2024. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/may-influencer-marketing-report/ (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Jiang, X., Liu, L., Wu-Ouyang, B., Chen, L., & Lin, H. (2024). Which storytelling people prefer? Mapping news topics and news engagement in social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 158, 108248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Liu, B. F., & Austin, L. L. (2014). Examining the role of social media in effective crisis management: The effects of crisis origin, information form, and source on publics’ crisis responses. Communication Research, 41(1), 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2021). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnes, Ø., & Bjørge, N. M. (2025). ‘So, we have occupied TikTok’: Ukrainian women in #ParticipativeWar. Media, War & Conflict, 18(2), 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Karalis, M. (2024, February 2). The Information War: The Russia–Ukraine Conflict Through the Eyes of Social Media. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Available online: https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2024/02/02/russia-ukraine-through-the-eyes-of-social-media/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communications. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kishore, S., & Errmann, A. (2024). Doing big things in a small way: A social media analytics approach to information diffusion during crisis events in digital influencer networks. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 28, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, C. G., Lehtisaari, K., Grönlund, M., & Villi, M. (2021). Journalistic passion as commodity: A managerial perspective. Journalism Studies, 22(12), 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. F., Jin, Y., & Austin, L. (2023). Digital crisis communication theory: Current landscape and future trajectories. In Public relations theory III (pp. 191–212). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lockett, D. (2024). Cognitive landscapes: Argument evaluations, misinformation corrections, and racial attitudes in modern media [Doctoral dissertation, Washington University in St. Louis]. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, T. (2022, March 11). White House turns to TikTok stars to spread its message on Ukraine. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/03/11/tik-tok-ukraine-white-house/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Lynch, M., Freelon, D., & Aday, S. (2014). Syria’s socially mediated civil war. United States Institute of Peace. Peaceworks No. 91. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/176084/PW91-Syrias%20Socially%20Mediated%20Civil%20War.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Marks, E. (2022, March 21). Ukrainian influencers are using TikTok to show the truth. 34th Street Magazine. Available online: https://www.34st.com/article/2022/03/ukraine-russia-war-tik-tok-putin-valeria-bomb-shelter-refugee (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Marsen, S. (2020). Navigating crisis: The role of communication in organizational crisis. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(2), 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, L. (2025, May 14). The female keyboard warriors taking on Myanmar’s military junta. Index on Censorship. Available online: https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2025/05/women-keyboard-warriors-myanmars-military-junta-digital-activism/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2013, August 26). Another casualty of war in Syria—Citizen journalists. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2013/08/26/another-casualty-of-war-in-syria-citizen-journalists/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Reynolds, B., & Seeger, M. W. (2005). Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication, 10(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rippberger, S. (2020). Meme warfare: Youth culture, social media, and nationalism in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Journal of Conflict and Media, 3(1), 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M., & Tran, M. V. (2024). Democratic Backsliding Disrupted: The Role of Digitalized Resistance in Myanmar. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 9(1), 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saed, O. (2023, May 4). A digital campaign to save the people of Sudan. New Lines Magazine. Available online: https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/a-digital-campaign-to-save-the-people-of-sudan/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Shao, Z. (2024). How the characteristics of social media influencers and live content influence consumers’ impulsive buying in live streaming commerce? The role of congruence and attachment. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, N. (2025, May 30). The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD): The role of diaspora finance in fostering national unity. LinkedIn. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/grand-ethiopian-renaissance-dam-gerd-role-diaspora-finance-simmonds-zgkbe (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- SIWI. (n.d.). Network members: Women in water diplomacy network in the Nile. Stockholm International Water Institute. Available online: https://siwi.org/swp-women-in-water-diplomacy-network/network-members (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- SIWI. (2020, October 1). Lessons from the women in water diplomacy network in the Nile. Stockholm International Water Institute. Available online: https://siwi.org/latest/lessons-from-the-women-in-water-diplomacy-network-in-the-nile/ (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Sjösvärd, K. (2024). Swift trust in extreme contexts: The impact of leadership in international crisis-and disaster management response. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1894004/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Stieglitz, S., Mirbabaie, M., & Milde, M. (2018). Social Positions and Collective Sense-Making in Crisis Communication. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 34(4), 328–355. [Google Scholar]

- Su, B. C., Wu, L. W., Chang, Y. Y. C., & Hong, R. H. (2021). Influencers on social media as references: Understanding the importance of parasocial relationships. Sustainability, 13(19), 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K., Zhao, T. F., Wu, X. K., Yang, L., Jin, D., & Chen, W. N. (2023). Mining multiplatform opinions during public health crisis: A comparative study. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems, 11(2), 2121–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Thorson, K., & Wells, C. (2016). Curated flows: A framework for mapping media exposure in the digital age. Communication Theory, 26(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Veil, S. R., Buehner, T., & Palenchar, M. J. (2011). A work-in-progress literature review: Incorporating social media in risk and crisis communication. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 19(2), 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, M., & El Zahed, S. (2014). Syrian citizen journalism: A pop-up news ecology in an authoritarian space. Digital Journalism, 3(5), 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., & Yecies, B. (2024). Pandemic-incited intermediated communication|Intermediated communication via Social Media platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic—Introduction. International Journal of Communication, 18, 2828–2836. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. (2025, May 15). Aaron Parnas. Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aaron_Parnas (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Yang, J., Chuenterawong, P., Lee, H., Tian, Y., & Chock, T. M. (2023). Human versus virtual influencer: The effect of humanness and interactivity on persuasive CSR messaging. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 23(3), 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Chen, F., & Lukito, J. (2023). Network amplification of politicized information and misinformation about COVID-19 by conservative media and partisan influencers on Twitter. Political Communication, 40(1), 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A., & Yang, A. (2021). The longitudinal dimension of social-mediated movements: Hidden brokerage and the unsung tales of movement spilloverers. Social Media + Society, 7(3), 20563051211047545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taher, A.; El Kolaly, H.; Tarek, N. Examining Crisis Communication in Geopolitical Conflicts: The Micro-Influencer Impact Model. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030116

Taher A, El Kolaly H, Tarek N. Examining Crisis Communication in Geopolitical Conflicts: The Micro-Influencer Impact Model. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030116

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaher, Ahmed, Hoda El Kolaly, and Nourhan Tarek. 2025. "Examining Crisis Communication in Geopolitical Conflicts: The Micro-Influencer Impact Model" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030116

APA StyleTaher, A., El Kolaly, H., & Tarek, N. (2025). Examining Crisis Communication in Geopolitical Conflicts: The Micro-Influencer Impact Model. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030116