The Politics of Framing Water Infrastructure: A Topic Model Analysis of Media Coverage of India’s Ken-Betwa River Link

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Framing Theory and Evolution

1.2. Historical and Critical Contexts of Water Infrastructure Discourse in India

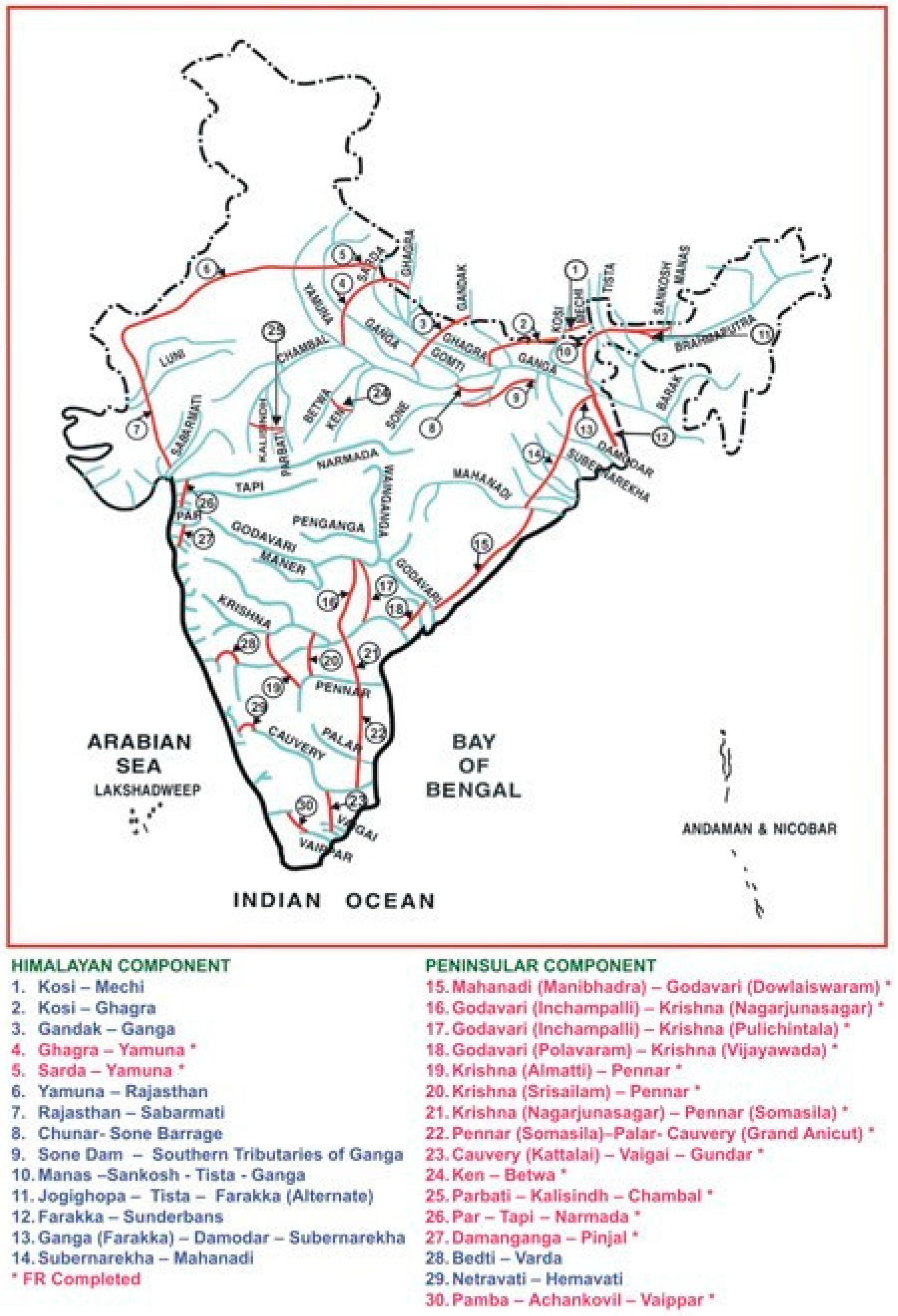

1.3. Contentious New Water Infrastructure: The Indian National River Linking Project (INRLP) and the Ken-Betwa Water Transfer Link

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Method and Research Design

2.2.1. Data Pre-Processing

2.2.2. Identifying the Number of Topics (k)

2.2.3. Testing the Validity of the Topic Model

3. Results

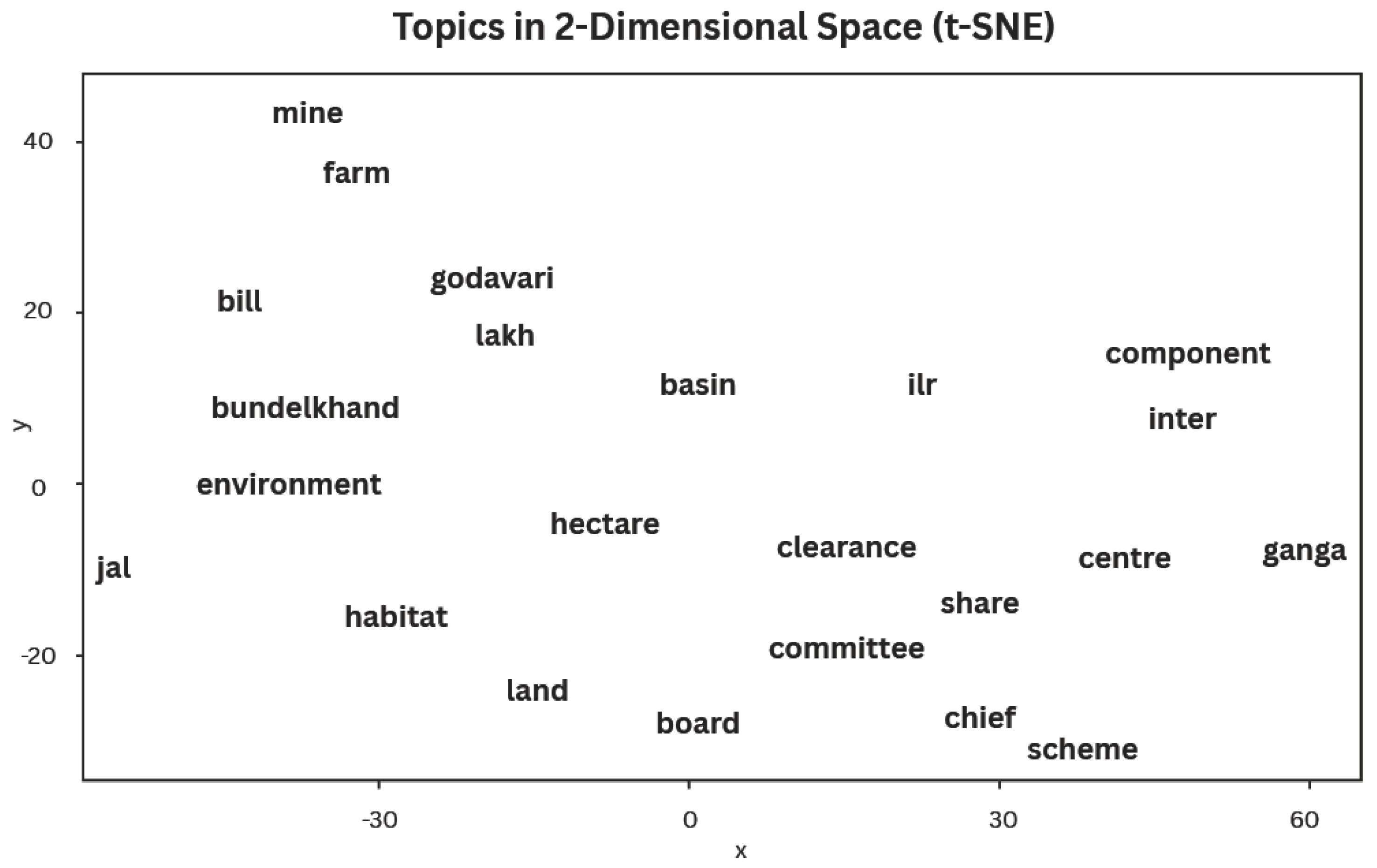

3.1. What Topics Can Be Identified?

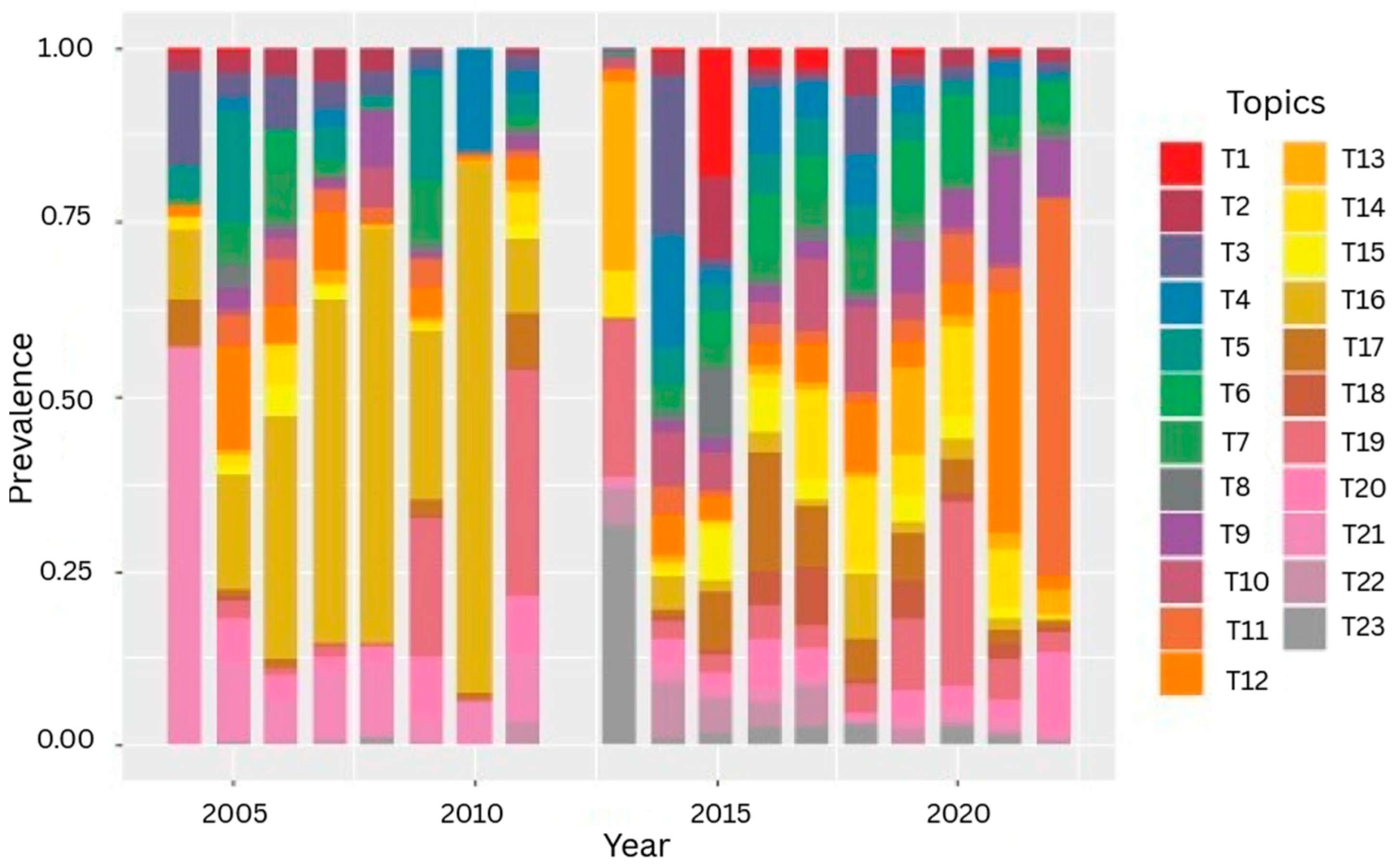

3.2. How Prevalent Are These Topics Between 2004 and 2022?

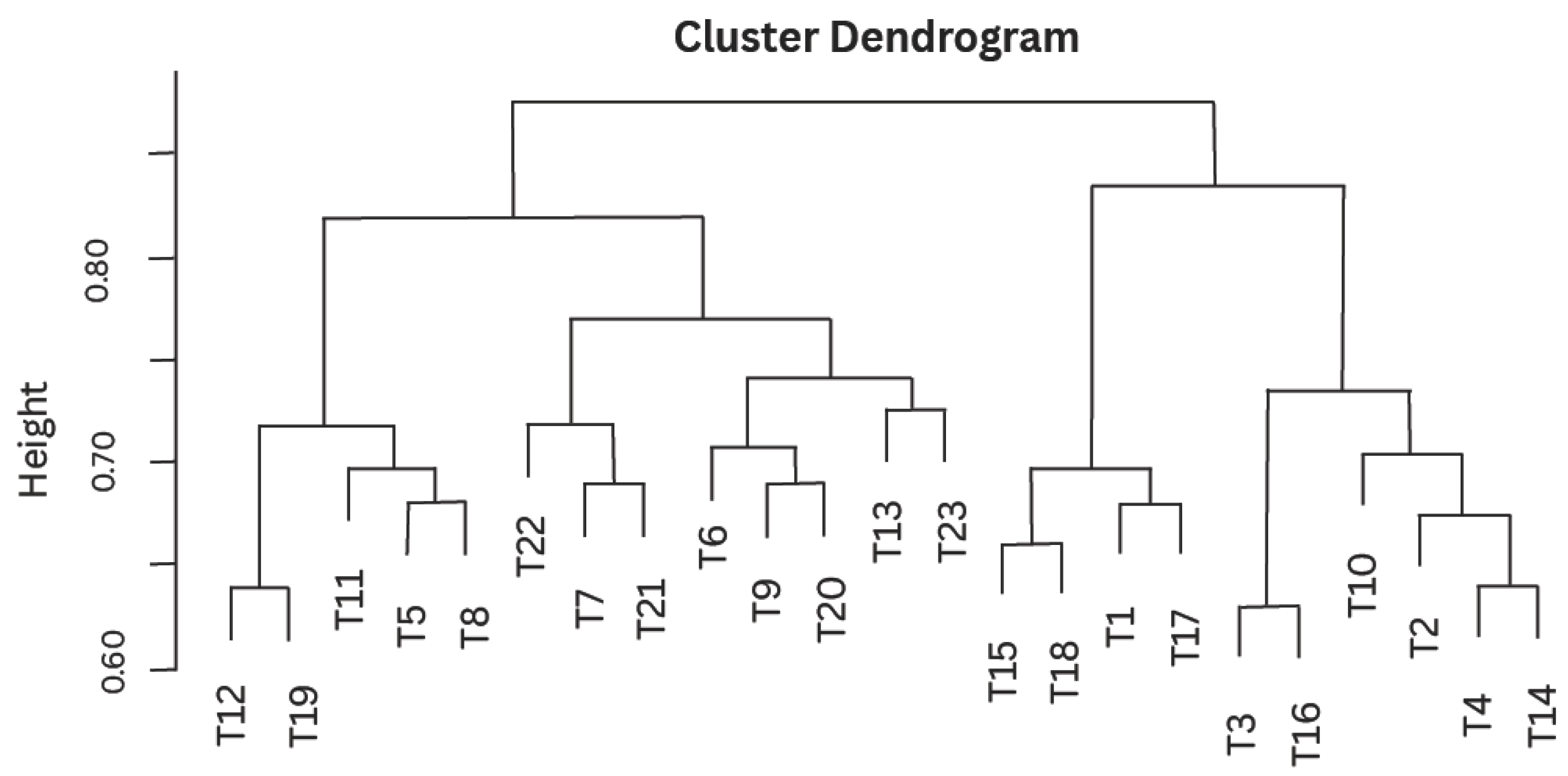

3.3. How Are These Topics Related to Each Other?

4. Discussion: The Politics of Framing Water

4.1. Government Policy Frame

4.2. INRLP Comparative Frame

4.3. Environmental Conservation Frame

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alghamdi, R., & Alfalqi, K. (2015). A survey of topic modeling in text mining. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA), 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtar, R., Kumar, P., Singh, C. K., & Mukherjee, S. (2011). A comparative study on hydrogeochemistry of Ken and Betwa rivers of Bundelkhand using statistical approach. Water Quality, Exposure and Health, 2(3–4), 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagla, P. (2006). Controversial rivers project aims to turn India’s fierce monsoon into a friend. Science, 313(5790), 1036–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, J., & Perveen, S. (2008). The interlinking of Indian rivers: Questions on the scientific, economic and environmental dimensions of the proposal. In Interlinking of rivers in India (pp. 75–98). CRC Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barde, B. V., & Bainwad, A. M. (2017, June 15–16). An overview of topic modeling methods and tools. 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS) (pp. 745–750), Madurai, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of the mind. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baviskar, A. (2007). Waterscapes: The cultural politics of a natural resource. Permanent Black. [Google Scholar]

- Best, J. (2013). Constructionist social problems theory. Annals of the International Communication Association, 36(1), 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D. (2023). India’s new water works. Current History, 122(843), 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, S. J., Bi, Y., & Mulvenna, M. D. (2020). Aggregated topic models for increasing social media topic coherence. Applied Intelligence, 50(1), 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D., Ng, A., & Jordan, M. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Brossard, D., Shanahan, J., & McComas, K. (2004). Are issue-cycles culturally constructed? A comparison of French and American coverage of global climate change. Mass Communication and Society, 7(3), 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappella, J. N., & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha, K. (2017). The Indian news media industry: Structural trends and journalistic implications. Global Media and Communication, 13(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Thorson, K., & Lavaccare, J. (2022). Convergence and divergence: The evolution of climate change frames within and across public events. International Journal of Communication, 16, 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Crow-Miller, B., Webber, M., & Molle, F. (2017). The (re)turn to infrastructure for water management? Available online: https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol10/v10issue2/351-a10-2-1/file (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. (1992). Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International, 13(3), 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, A. (1998). Up and down with ecology—The “Issue-Attention Cycle”. In Political theory and public choice (pp. 100–112). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A. F., Bandyopadhyay, S., Louçã, J., & Manjaly, J. A. (2019). Caste in the news: A computational analysis of Indian newspapers. Social Media + Society, 5(4), 205630511989605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, M., & Guha, R. (2013). Ecology and equity: The use and abuse of nature in contemporary India. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1987). The changing culture of affirmative action. In Research in political sociology (Vol. 3, pp. 137–177). JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, B. (2019). Making water media in 21st-century South Asia. In Water histories of South Asia (pp. 226–242). Routledge India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, D., Raffin, M., Jeffrey, P., & Smith, H. M. (2018). Evaluating media framing and public reactions in the context of a water reuse proposal. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 34(6), 848–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, J., & Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis, 21(3), 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, B., & Hornik, K. (2011). topicmodels: An R package for fitting topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, 40(13), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, R. (2006). How much should a person consume? Permanent Black. [Google Scholar]

- Hopp, F. R., Fisher, J. T., & Weber, R. (2020). Dynamic transactions between news frames and sociopolitical events: An integrative, hidden Markov model approach. Journal of Communication, 70(3), 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R. (2012). River linking project: A disquieting judgment. Economic and Political Weekly, 14(14), 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H., Qiang, M., & Lin, P. (2016). Assessment of online public opinions on large infrastructure projects: A case study of the Three Gorges Project in China. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 61, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H., Qiang, M., Lin, P., Wen, Q., Xia, B., & An, N. (2017). Framing the Brahmaputra River hydropower development: Different concerns in riparian and international media reporting. Water Policy, 19(3), 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, G., Kiparsky, M., Milman, A., & Ray, I. (2006). Glossing over the complexity of water. Science, 314(5804), 1387–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kee, C. P., Ismail, N. S., Hashim, N., & Nie, K. S. (2013). Framing Bersih 3.0: Online versus traditional mass communication. Procedia Technology, 11, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T. R., Hase, V., Thaker, J., Mahl, D., & Schäfer, M. S. (2020). News media coverage of climate change in India 1997–2016: Using automated content analysis to assess themes and topics. Environmental Communication, 14(2), 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, K. E. C., & Franklin, M. (2014). Using topic models to examine political contention in the U.S. trucking industry. Social Science Computer Review, 32(2), 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Tang, L., Dong, W., Yao, S., & Zhou, W. (2016). An overview of topic modeling and its current applications in bioinformatics. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacRobert, C. J. (2020). A review of impacts associated with infrastructure news coverage in South Africa. South African Geographical Journal, 102(2), 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D., Waldherr, A., Miltner, P., Wiedemann, G., Niekler, A., Keinert, A., Pfetsch, B., Heyer, G., Reber, U., Häussler, T., Schmid-Petri, H., & Adam, S. (2018). Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: Toward a valid and reliable methodology. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(2–3), 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccomas, K., & Shanahan, J. (1999). Telling stories about global climate change. Communication Research, 26(1), 30–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K., Patel, A., Singh, V., Prajapati, S., Kalubarme, M. H., Prakash, I., & Gupta, K. P. (2014). Submergence analysis using geo-informatics technology for proposed Dam reservoirs of Par-Tapi-Narmada River link project, Gujarat State, India. International Journal of Geosciences, 5(6), 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M. (2020). Environmental journalism in India: Past, present, and future. In Routledge hand-book of environmental journalism (pp. 291–305). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, R. (2018). Democratizing development: Struggles for rights and social justice in India. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mollinga, P. P. (2008). Water, politics and development: Framing a political sociology of water resources management. Water Alternatives, 1(1), 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, F., & Legendre, P. (2014). Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: Which algorithms implement ward’s criterion? Journal of Classification, 31(3), 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, T., & Arul, A. (2017). Framing of environment in English and Tamil newspapers in India. Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 9(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obertreis, J., Moss, T., Mollinga, P., & Bichsel, C. (2016). Water, infrastructure and political rule: Introduction to the special issue. Water Alternatives, 9(2), 168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori-Birikorang, A. (2019). News construction on the pivots of framing and ideology: A theoretical perspective. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 9(2), 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooms, J. (2018). hunspell: High-performance stemmer, tokenizer, and spell checker. (version 3). R Archive Network. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, A. (2025). Representation of freshwater access, equity; Community empowerment in leading mainstream vernacular newspapers: A sustainable development perspective in Indian Sundarban Region’s Moushuni and Gobordhanpaur Islands. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 7(3), 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, T., & Ilyas, O. (2021). The inter-linking of rivers and biodiversity conservation: A study of Panna Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh, India. Current Science, 121(12), 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, H. (2016). Socio-economical, environmental evaluation of Ken-Betwa River link project, India. Present Environment and Sustainable Development, 10(2), 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popik, B. (2004). Digital historical newspapers. Journal of English Linguistics, 32(2), 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, R. (2024). Reframing the narrative: An analysis of print media reporting on Bihar floods. Frontiers in Water, 6, 1039240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesnel, K. J., & Ajami, N. K. (2017). Changes in water consumption linked to heavy news media coverage of extreme climatic events. Science Advances, 3(10), e1700784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A. (2018). National river linking project significance & challenges. International Education and Research Journal, 4, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ramage, D., Rosen, E., Chuang, J., Manning, C., & McFarland, D. (2009). Topic modeling for the social sciences. NIPS-Workshop on Applications for Topic Models: Text and Beyond, 5(27), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi Rajan, S. (2014). A history of environmental justice in India. Environmental Justice, 7(5), 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A., Ghatak, D., Khanuja, G., Rekha, K., Gupta, M., Dhakate, S., Sharma, K., & Seth, A. (2022, June 29–July 1). Analysis of media bias in policy discourse in India. ACM SIGCAS/SIGCHI Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (COMPASS) (pp. 57–77), Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. H. (2019). How episodic frames gave way to thematic frames over time: A topic modeling study of the Indian media’s reporting of rape post the 2012 Delhi gang-rape. Poetics, 72, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G. D. P. d., Sherren, K., & Parkins, J. R. (2021). Using news coverage and community-based impact assessments to understand and track social effects using the perspectives of affected people and decisionmakers. Journal of Environmental Management, 298, 113467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhija, N., Tatineni, M., Brown, N., Van Moer, M., Rodriguez, P., & Callicott, S. (2016, July 18–21). Topic modeling and visualization for big data in social sciences. 2016 Intl IEEE Conferences on Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced and Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing and Communications, Cloud and Big Data Computing, Internet of People, and Smart World Congress (UIC/ATC/ScalCom/CBDCom/IoP/SmartWorld) (pp. 1198–1205), Toulouse, France. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, L. (2021). Environmental geotechnical issues in river interlinking proposal (pp. 149–157). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2023). Valuing hydraulic infrastructure. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Maaten, L., & Hinton, G. (2008). Visualizing data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Vayansky, I., & Kumar, S. A. P. (2020). A review of topic modeling methods. Information Systems, 94, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedachalam, S., Lewenstein, B. V., DeStefano, K. A., Polan, S. D., & Riha, S. J. (2016). Media discourse on ageing water infrastructure. Urban Water Journal, 13(8), 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreese, C. H. (2005). News framing. Information Design Journal, 13(1), 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. H. (1963). Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58(301), 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weder, F., Voci, D., & Vogl, N. C. (2019). (Lack of) Problematization of water supply use and abuse of environmental discourses and natural resource related claims in German, Austrian, Slovenian and Italian media. Journal of Sustainable Development, 12(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, S. (2020). foreach: Provides foreach looping construct. (version. 1.5.1). R Archive Network. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H., & Wickham, M. (2019). Package ‘stringr’. Available online: https://github.com/tidyverse/stringr (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Yang, T.-I., Torget, A., & Mihalcea, R. (2011, June 4). Topic modeling on historical newspapers. 5th ACL-HLT Workshop on Language Technology for Cultural Heritage, Social Sciences, and Humanities (pp. 96–104), Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

| Newspaper Sources | No. of Articles |

|---|---|

| Hindustan Times | 100 |

| The Times of India paper edition (TOI) | 77 |

| The Times of India (Electronic Edition) | 42 |

| Indian Express | 32 |

| The Economic Times | 27 |

| Free Press Journal (India) | 22 |

| The Hindu | 16 |

| Total | 316 |

| Topics | Labels | Perspective Labels | Prevalence | Top 5 Terms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic 12 | Lakh/Project Cost (unit in the Indian numbering system equal to 100,000, in this case, referring to INR) | Irrigation and river sharing agreement | 8.32% | hectare, budget, agriculture, lakh, power |

| Topic 17 | Committee | Environmental impact assessment and clearances | 7.36% | committee, dam, clearance, expert, impact |

| Topic 14 | Share | Water sharing demands and needs | 5.79% | share, house, speak, bjp, amend |

| Topic 16 | Component | Feasibility for peninsular components | 5.73% | component, nwda, feasibility, peninsular, tail |

| Topic 4 | Clearance | Supreme court government clearance process | 5.67% | clearance, district, court, bharti, centre |

| Topic 19 | Bundelkhand | Bundelkhand politics | 5.44% | bundelkhand, region, people, add, congress |

| Topic 5 | Basin | Interbasin transfer and water quantity | 5.24% | basin, transfer, flow, country, drought |

| Topic 10 | IRL (Indian River Linking) | Narmada River interlinking | 5.11% | ilr, gujarat, maharashtra, narmada, tapi |

| Topic 6 | Habitat | Wildlife conservation and habitat | 4.69% | habitat, conservation, specie, population, wild |

| Topic 9 | Jal (water in Hindi) | Water nationalism | 4.23% | country, jal, day, campaign, world |

| Topic 20 | Environment | Climate change policy | 4.13% | environment, change, people, manage, time |

| Topic 11 | Farm | Agricultural funding and budget | 4.04% | farm, budget, agriculture, lakh, power |

| Topic 3 | Inter | INRLP implementation | 3.98% | inter, component, yamuna, nepal, ganga |

| Topic 7 | Chief | Project authority and implementation | 3.86% | chief, department, office, official, secretary |

| Topic 1 | Board | Central government agencies | 3.80% | board, director, field, nwda, chief |

| Topic 15 | Hectare (a metric unit of square measure) | Land submergence | 3.53% | hectare, km, land, basin, involve |

| Topic 22 | Ganga | Ganga rejuvenation | 3.53% | ganga, bharti, clean, pollute, rejuvenate |

| Topic 2 | Centre | Central government with national concerns | 3.34% | centre, include, ganga, bihar, cost |

| Topic 18 | Land | Environment and land | 3.30% | land, hectare, commend, diverse, committee |

| Topic 21 | Scheme | Central government schemes | 2.82% | scheme, flood, manage, central, complete |

| Topic 8 | Godavari | Peninsular interlinking | 2.47% | interlink, godavari, million, scheme, andhra |

| Topic 23 | Mine | Environmental challenges: mining and sugar | 1.85% | mine, sugar, diamond, bhopal, white |

| Topic 13 | Bill | Parliament legislation and amendments | 1.78% | bill, house, speak, bjp, amend |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, H.; Hansen, M.; Birkenholtz, T. The Politics of Framing Water Infrastructure: A Topic Model Analysis of Media Coverage of India’s Ken-Betwa River Link. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030114

Singh H, Hansen M, Birkenholtz T. The Politics of Framing Water Infrastructure: A Topic Model Analysis of Media Coverage of India’s Ken-Betwa River Link. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030114

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Harman, Matthew Hansen, and Trevor Birkenholtz. 2025. "The Politics of Framing Water Infrastructure: A Topic Model Analysis of Media Coverage of India’s Ken-Betwa River Link" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030114

APA StyleSingh, H., Hansen, M., & Birkenholtz, T. (2025). The Politics of Framing Water Infrastructure: A Topic Model Analysis of Media Coverage of India’s Ken-Betwa River Link. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030114