Digital Activism for Press Freedom Advocacy in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Digital Activism and Freedom of the Press

- First, spectator. Participants and initiators of digital activism are involved in clicktivism, metavoicing, and assertion activities. All three are basic activities that anyone can perform with various levels of digital literacy;

- Second, transitional. Participants and managers of activism platforms develop more systematic activities: political consumerism, joint digital petitions, botivism, and fundraising to maintain activities sustainability;

- Third, gladiatorial. Digital activism platform managers increasingly involve their participants in organized, intelligent, and comprehensive activities: data activism, exposure, and hacktivism.

3. Method

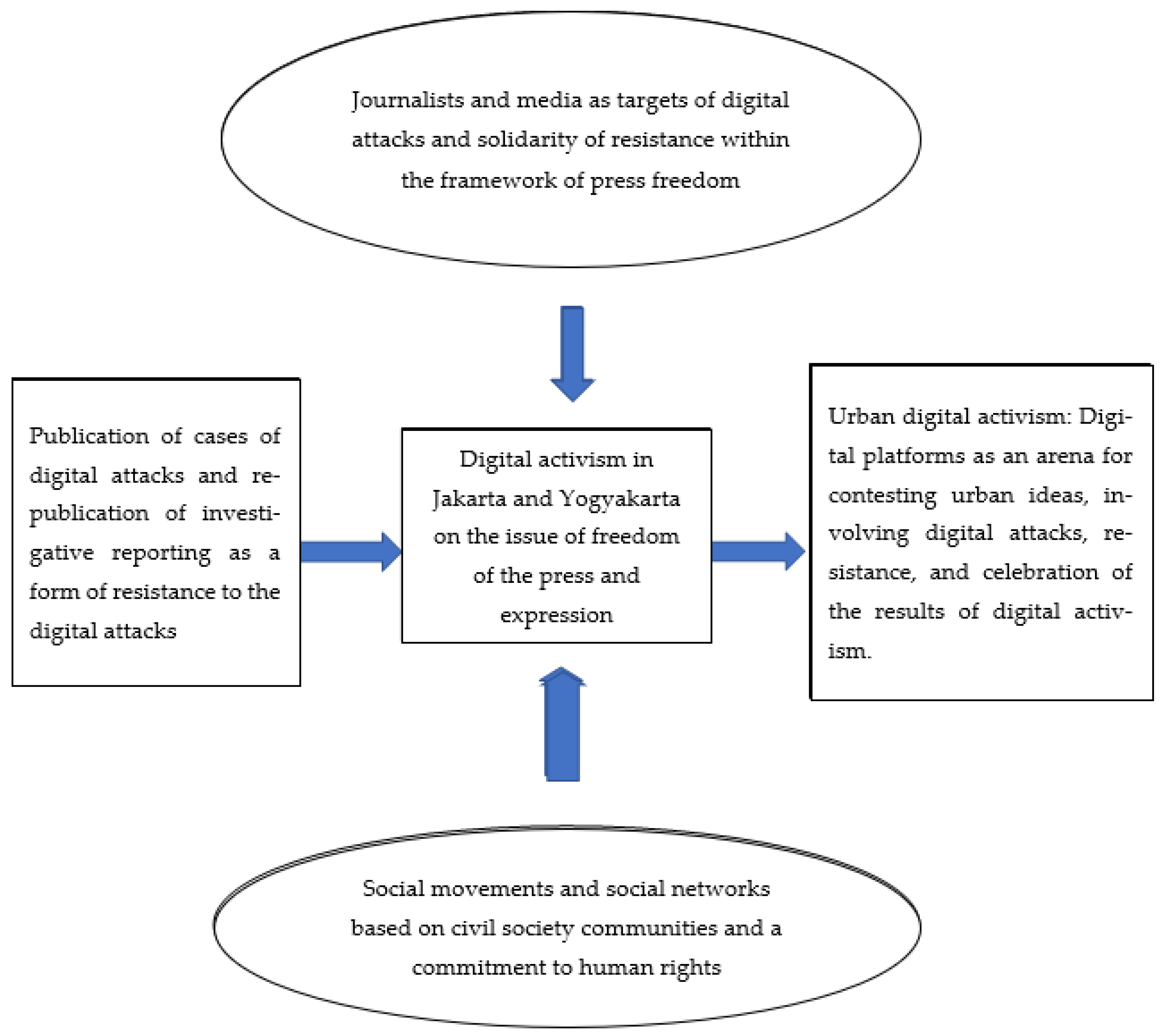

4. Results and Discussion

- https://www.walhi.or.id/chronology-of-event-and-analysis-of-legal-and-human-rights-violation-of-agrarian-conflict-in-wadas (accessed on 15 January 2024);

- https://www.foei.org/internationalist-solidarity-with-wadas-indonesia/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aanabh, R. (2024). Press freedom in India: A complete analysis. International Journal of Research and Publication Review, 5(8), 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) Indonesia. (2024). Catatan 2024: Keluar dari mulut harimau, masuk ke mulut buaya. AJI Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Angiana, R. (2022). The United Nations in Indonesia welcomes the Indonesian Parliament’s approval of the Sexual Violence Crime Bill (RUU TPKS) into law on 12 April 2022. The UN in Indonesia. Available online: https://indonesia.un.org/en/177437-united-nations-indonesia-welcomes-indonesian-parliament%E2%80%99s-approval-sexual-violence-crime (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Boshnakova, D., & Dankova, D. (2023). The media in eastern Europe. In S. Papathanassopolous, & A. Miconi (Eds.), The media system in Europe. Studies in Media and Political Communication. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. (2019). The global disinformation order: 2019 global inventory of organized social media manipulation. Oxford Internet. [Google Scholar]

- Brauchler, B. (2020). Bali Tolak Reklamasi: The local adoption of global protest. Convergence. International Journal for Research into New Media Technologies, 26(3), 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidiac, M., & Elhajj, M. (2019). Digital media and freedom of expression: Experiences, challenges and resolutions. Global Media Journal, 17, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. (2009). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative, and mixed method approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, K., & Lincoln, Y. (2017). The sage handbook of qualitative resarch. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Dewantara, R., & Widhyharto, D. (2015). Aktivisme dan kesukarelawanan dalam media sosial komunitas kaum muda Yogyakarta. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, 19(1), 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajar, M., Adam, L., Nastiti, A., & Kenawas, Y. (2022). Aktivisme digital di Indonesia. Yayasan Tifa. [Google Scholar]

- Freedom House. (2025). Country profile: Indonesia. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Fuadi, A. (2020). Social media power for protest in Indonesia: The Yogyakarta’s @gejayanmenanggil case study. Jurnal Studi Komunikasi, 4(3), 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J., & Leidner, D. (2019). From clictivism to hacktivism: Understanding digital activism. Information and Organization, 29(3), 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, S., & Mate, R. (2024). Press freedom in Asian countries (2010–2023): A systematic literature review. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(5), 7453–7461. [Google Scholar]

- Jati, W. (2016). Cyberspace, internet dan ruang publik baru: Aktivisme online politik kelas menengah di Indonesia. Jurnal Pemikiran Sosiologi, 3(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Joyce, M. (2010). Introduction: How to think about digital activism. In M. Joyce (Ed.), Digital activism decoded: The new mechanics of change (pp. 1–14). International Debate Education Association. [Google Scholar]

- Jurriëns, E., & Tapsell, R. (2017). Challenges and opportunities of the digital “revolution” in Indonesia. In E. Dalam Jurriëns, & R. Tapsell (Eds.), Digital Indonesia: Connectivity and divergence (Vol. 1, p. 1). ISEAS. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, M. (2005). The internet and political activism in Indonesia. University of Twente. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, M. (2013). Many clicks but little sticks: Social media activism in Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 43(4), 636–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. (2014). Seeing spatially: People, networks and movements in digital and urban spaces. International Development Planning Review, 36(1), 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LP3ES. (2022). RKUHP dan problem aktivisme digital saat Ini. Available online: https://www.lp3es.or.id/2022/07/21/rkuhp-dan-problem-aktivisme-digital-saat-ini/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Masduki. (2021). The politics of disinformation (2014–2019). In G. Lopez-Garcia, D. Palau-Sampio, B. Palomo, E. Campos-Dominguez, & P. Masip (Eds.), Politics of disinformation. Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Masduki, Arif, A., Galuh, F., Wendratama, E., & Suci, P. L. N. (2025). Potret jurnalis Indonesia: Demografi, budaya kerja, kompetensi digital, dan kekerasan terhadap jurnalis. AJI Indonesia. Available online: https://aji.or.id/data/potret-jurnalis-indonesia-2025-demografi-budaya-kerja-kompetensi-digital-dan-kekerasan (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- McChesney, R. (2008). The political economy of media: Enduring issues, emerging dilemmas. Monthly Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Melki, J., & Malat, S. (2014). Digital activism: Efficacies and burdens of social media for civic activism. Arab Media & Society, (19), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Misel, R. (2004). Teori pergerakan sosial. Resist Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nofrima, S., Suluh, D., Nurmandi, A., & Salahudin, S. (2020). Cyberactivism on the dissemination of #GejayanMemanggil: Yogyakarta’s student movement. Jurnal Studi Komunikasi, 4(1), 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho, Y., & Syarief, S. (2012). Melampaui aktivisme click? Media baru dan proses politik dalam Indonesia kontemporer. FES. [Google Scholar]

- Postill, J. (2012). Digital politics and political engagement. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Priyonggo, A., Haryanto, I., Pramadiba, I. I., Winaldi, I., & Prestianta, A. M. (2024). Lanskap dan dampak digitalisasi terhadap model bisnis serta dinamika redaksi industri media di Indonesia. Dewan Pers. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, B. (2024). Digital activism in southeast Asia: The #MilkteaAlliance and prospect for social resistance. Frontiers in Sociology, 9, 1478630. [Google Scholar]

- Reporters Sans Frontieres. (2025). RSF world press freedom index 2025: Economic fragility a leading threat to press freedom. RSF. Available online: https://rsf.org/en/rsf-world-press-freedom-index-2025-economic-fragility-leading-threat-press-freedom (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Sadasri. (2019). Kaum muda dan aktivisme politik daring di Indonesia. Prosiding Commnews. [Google Scholar]

- Suwana, F. (2020). What motivates digital activism? The case of Save KPK movement in Indonesia. Information, Communication and Society, 23(9), 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajudin, Q. (2025). Kondisi keamanan jurnalis 2024: Masih belum terlindungi. Jurnalisme Aman. Available online: https://jurnalismeaman.com/blog/kondisi-keamanan-jurnalis-2024-masih-belum-terlindungi (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Tapsell, R. (2012). Trik lama di era baru: Swasensor dalam jurnalisme Indonesia. Jurnal Komunikasi Indonesia, 1(2), 2. Available online: https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/jkmi/vol1/iss2/2 (accessed on 15 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Trere, E., & Kaun, E. (2021). Digital media activism: A situated, historical, and ecological approach beyond the technological sublime. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, E., & Aspinall, E. (2019). Explaining Indonesia’s democratic regression: Structure, agency and popular opinion. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 41(2), 255–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendratama, E., Masduki, Aprilia, M. P., & Suci, P. L. N. (2023). Sexual violence against Indonesian female journalists. AJI Indonesia. Available online: https://pr2media.or.id/publikasi/research-report-sexual-violence-against-indonesian-female-journalists/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Wisanjaya, I., & Widodo, P. (2024). Freedom of expression on social media in Indonesia: Why are the limitations imposed? Udayana Journal of Law and Culture, 8(1), 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahira, D., & Hermanadi, H. (2018). Mapping the stream of digital activism. Center for Digital Society. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Traditional Activism | Digital Activism |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | The success of activism is determined by awareness of issue and the number of participants | The success of activism is determined by the efficiency of messages and spaces that have a broad impact: the change of a targeted policy. |

| Participant age tendencies | Tend to be mature or adult | Tend to be young with high digital literacy |

| Criteria for success in managing issues | Number of participants involved, adequate financial resources, etc. | Good access to digital technology, digital social networks, etc. |

| Participant interaction models | Attending political meetings, street demonstrations, correspondence | Texting, being present in virtual spaces, engagement on social media |

| Impact on marginalized groups | Tends to be left behind due to constraints on access to resources | There are many options of spaces that are easy to access |

| Parameter | Political Middle Class | Apolitical Middle Class | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Themes and Issues that Establish Movement | Politics and economics | Lifestyle and entertainment |

| 2 | Movement Orientations | Pressure groups | Interest groups |

| 3 | Needs that Establish Movements | Need for achievement | Need for existence |

| 4 | Nature of Movements | Inclusive and communal | Exclusive and elite |

| 5 | Relations with the State | Oppositional–constructive | Dependent |

| Journalism Case | Background | Form of Activism |

|---|---|---|

| Hackings of the Project Multatuli website | News reporting on wrongful arrests made (poor performance shown) by the police in cases of violence against children and the cover-up by the police | Republication by other media, statements and conversations of the digital attack on social media, and digital engagement of Multatuli audiences who tend to be young with high digital literacy. Other media outlets, such as SuaraKita.org and Floresa.co, were also better equipped to handle digital attacks on their websites and social media accounts as a result of the Project Multatuli case. |

| Intimidation of journalists working on the Wadas case | News reporting that criticized the Central Java provincial government and its governors in relation to the Wadas case | A combination of online activism (digital posters, webinars, and news reporting) and offline activism (field reporting, fellowship for student journalists, and activist meetings at the AJI and LBH Yogyakarta offices) |

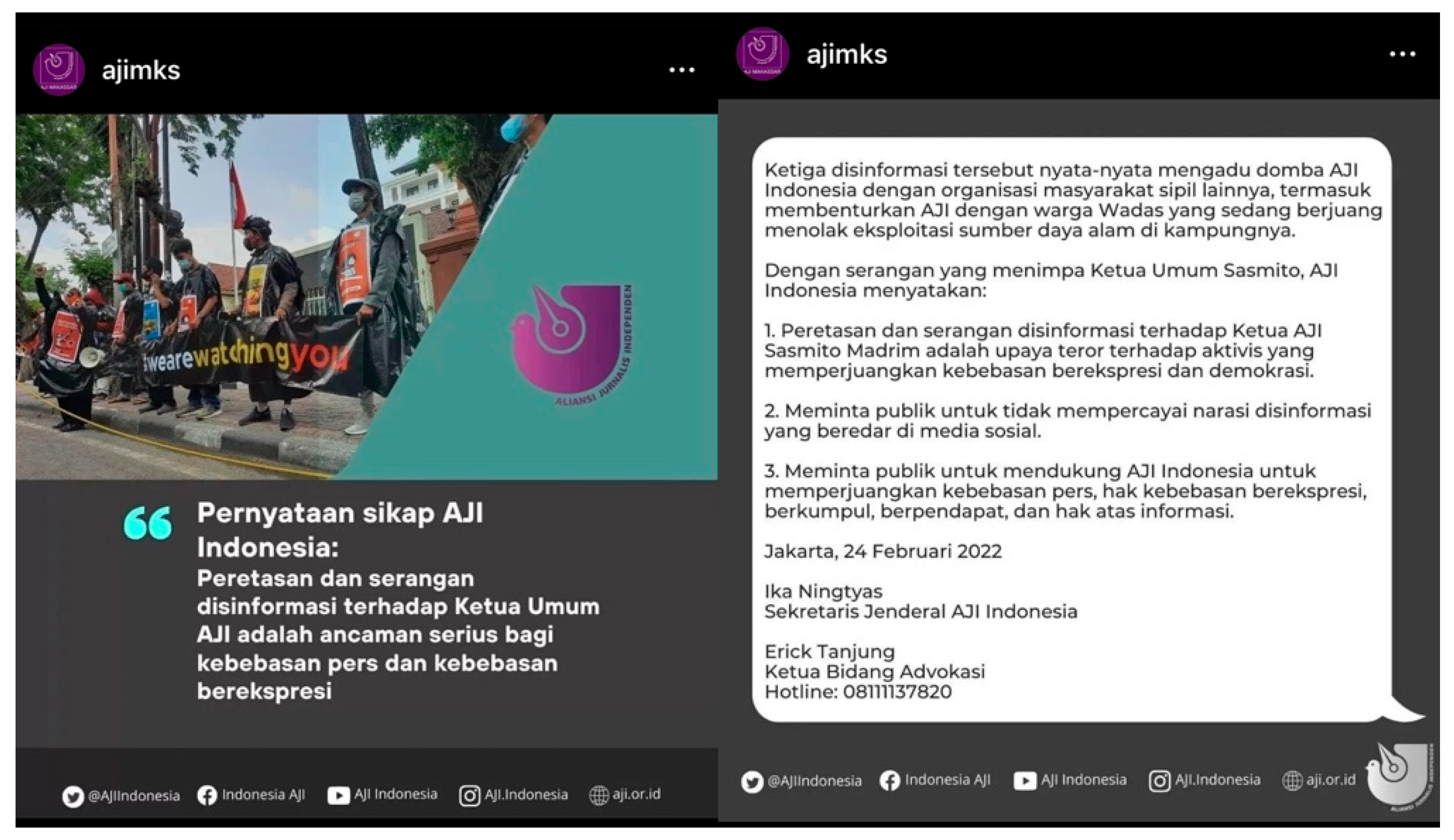

| Mobile phone hacking and disinformation attacks against Sasmito Madrim | It is suspected to be related to news reporting and activism on Papua | Discourse on AJI Indonesia and AJI cities social media accounts, access to digital platforms providers, and a solid network of journalist communities. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Masduki; Wendratama, E. Digital Activism for Press Freedom Advocacy in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030101

Masduki, Wendratama E. Digital Activism for Press Freedom Advocacy in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030101

Chicago/Turabian StyleMasduki, and Engelbertus Wendratama. 2025. "Digital Activism for Press Freedom Advocacy in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030101

APA StyleMasduki, & Wendratama, E. (2025). Digital Activism for Press Freedom Advocacy in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030101