De-Westernizing Media and Communication Theory in Practice: Toward a More Inclusive Theory for Explaining Exemplification Phenomena

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Effects of Exemplars on News Audiences

2.2. Exemplification Outcomes in Global South News Contexts

2.3. Exemplar Portrayal of Individual and Social Responsibility

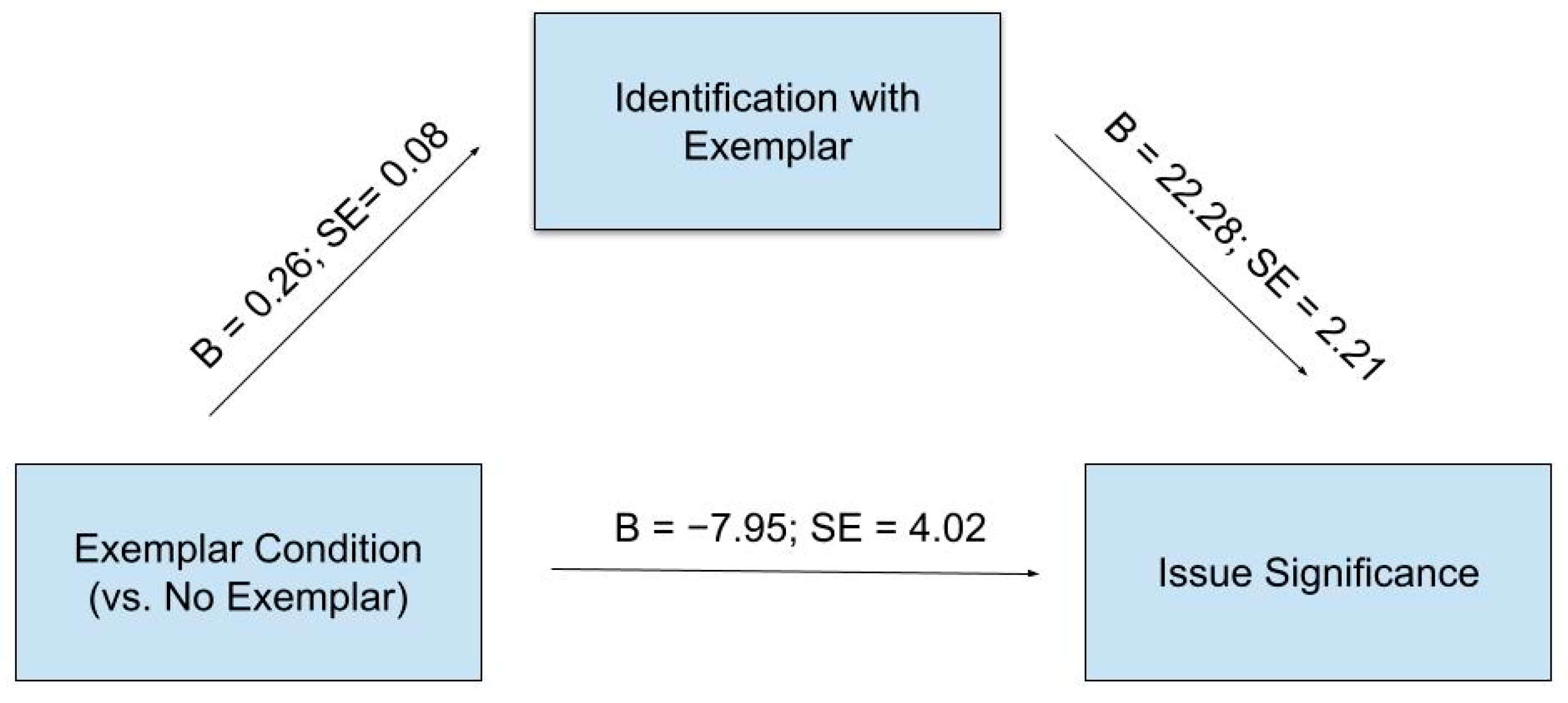

2.4. The Mediating Role of Identification

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experiment Overview and Sample

3.2. Experimental Protocol and Design

3.3. Independent Variable and Stimulus Materials

3.4. Mediating Variable

3.5. Dependent Variables

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations, Directions, and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Survey Questions

- Manipulation check (Yes/No/Not sure)

- The article I read included an example of a Nigerian living in poverty.

- The article I read included quotations from a Nigerian living in poverty.

- Attitude to story

- On a scale of 1–5, from strongly disagree to strongly agree, choose your agreement to the following statements:

- The story was interesting.

- I wanted to read the story all the way through.

- The story kept my attention.

- I would share the story on social media.

- I would talk about the story with others.

- iii.

- Mediating variables

- On a scale of 1–5 (from strongly disagree to strongly agree), choose your agreement to the following statements:

- Identification

- At key moments of reading the story, I felt I really understood persons living in poverty

- While reading the story, I understood the struggles of persons living in poverty the way such persons understand them

- While reading the story, I felt I could really ‘‘get inside’’ the head of a person living in poverty

- While reading the story, I could feel the emotions persons living in poverty feel

- While reading the story, I understood why persons living in poverty live their lives the way they live them

- Liking

- Thinking about the individual depicted in the story, I find that person likable.

- Thinking about the individual depicted in the story, I find that person pleasant.

- iv.

- Dependent Variables

- Issue Significance

- On a scale of 1–5, choose your agreement to the following statements about poverty in Nigeria:

- Poverty is a serious national problem in Nigeria

- Poverty is a real threat in the country for everyone

- In the next few years, more people are likely to become poor in Nigeria

- Poverty in Nigeria deserves more attention than it currently gets from the media

- Poverty in Nigeria deserves more attention than it currently gets from the government

- Poverty in Nigeria deserves more attention than it currently gets from the general public

- Attitudes and behavioral intentions

- On a scale of 1–5, choose your agreement to the following statements about poverty in Nigeria:

- Government should prioritize policies that improve the lives of people living in poverty

- Government officials who are not working to improve the lives of people living in poverty should resign or be replaced

- Everyone in society has an obligation toward persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Elites, most especially, have a responsibility toward persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Local organizations have an obligation toward persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- International organizations have an obligation toward persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- In the future, I will give money directly to persons living in poverty

- In the future, I will give money to a local organization working with persons living in poverty

- I will join a local organization that addresses the needs of persons living in poverty

- I will engage in activism to draw government attention to the issue of poverty in Nigeria

- I will help educate persons experiencing poverty through literacy initiatives to pull more people out of poverty.

- Impact of poverty and poverty interventions

- To what extent do you agree with the following statements about poverty in Nigeria? (strongly disagree--strongly agree)

- Poverty has a substantial impact on the wellbeing of persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Poverty affects the range of opportunities available to persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Poverty affects the future life outcomes of persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Current government policy has a strong positive impact on the lives of persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Current interventions by local organizations have a substantial positive impact on the lives of persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Current interventions by Nigerian elites have a strong positive impact on the lives of persons living in poverty in Nigeria

- Trust in Media

- Generally speaking, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about Nigerian media’s coverage of poverty? (strongly disagree--strongly agree)

- The media are fair when covering poverty

- The media are unbiased when covering poverty

- The media tell the whole story when covering poverty

- The media are accurate when covering poverty

- The media separate facts from opinions when covering poverty

- If citizen need help, the media will do its best to help them.

- The media acts in the interest of citizens.

- The media is genuinely interested in the well-being of citizens.

- Trust in Government

- Generally speaking, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the Nigerian government when it concerns poverty? (strongly disagree--strongly agree)

- The government is capable

- The government is effective

- The government is skillful

- The government is expert

- The government carries out its duty very well

- If citizens need help, the government will do its best to help them.

- The government acts in the interest of citizens.

- The government is genuinely interested in the well-being of citizens.

- The government approaches citizens in a sincere way.

- The government is sincere.

- The government keeps its commitments.

- The government is honest.

- Stigma

- In your opinion (on a scale of 1–5), how do most Nigerians perceive persons experiencing poverty?

- Capable

- Competent

- Efficient

- Skillful

- Industrious

- Intelligent

- Friendly

- Kind

- Likeable

- Nice

- Warm

- v.

- Demographic questions

- What is your current age group?

- 18–24 years

- 25–34 years

- 35–44 years

- 45–54 years

- 55–64 years

- 65 and older

- On the average, how many hours do you spend consuming news every week?

- 0–4 h

- 5–8 h

- 9–12 h

- 13–18 h

- 18 h and above

- Where do you consume news on the average? Select all that apply:

- Newspaper

- TV

- Radio

- Social media platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp)

- Informal conversations with people

- What is your highest level of education?

- Primary school education

- Secondary school education

- Post-secondary school vocational training

- OND/HND

- Bachelor’s degree

- Postgraduate diploma

- Master’s degree

- Doctorate degree

- What social class group do you identify with?

- Poor

- Lower middle class

- Upper middle class

- Affluent

- Which Nigerian geopolitical zone are you from?

- North Central (Benue, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, FCT)

- North East (Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, Yobe)

- North West (Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara)

- South East (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo)

- South South (Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, Rivers)

- South West (Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, Oyo)

- Where do you currently live?

- North Central (Benue, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, FCT)

- North East (Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, Yobe)

- North West (Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara)

- South East (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, Imo)

- South South (Akwa Ibom, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, Rivers)

- South West (Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, Oyo)

- Outside Nigeria. Please specify the country: _______________________

- What is your ethnic group?

- Hausa

- Igbo

- Yoruba

- Others, please specify: ________________________________________

- How do you currently describe your gender identity?

- Man

- Woman

- Non-binary

- Prefer not to say

- Others, please specify:

Appendix B. Stimulus Materials

Appendix B.1. Individual Responsibility + External View Condition

- By Jared ShuaibuThu, 26 Jan 2023 13:07:20 WATThe number of Nigerians living in poverty stands at over 133 million, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced Thursday. It said the figure represents 63 per cent of the nation’s population.The NBS disclosed this in its “Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index” released on Thursday. According to the report, over half of the population who are poor cook with dung, wood or charcoal, rather than cleaner energy.It said high deprivations are also apparent in sanitation, time to healthcare, food insecurity, and housing.For someone like Suleiman Nasiru who lives in Makoko, one of Lagos’s notorious slums, the figures are not surprising.Just like many residents of Makoko, Nasiru’s family does not have access to clean water. They use contaminated black water from the lagoon to wash their clothes and do house chores. They sometimes drink this water when they cannot afford to buy clean water.Nasiru has six children. None of them go to school because Nasiru does not work and cannot afford the school fees. He has given up on trying to get a job and instead spends most of his time at home, doing nothing.The NBS noted that multidimensional poverty is higher in rural areas, where 72 per cent of people are poor, compared to 42 per cent of people in urban areas.According to the report, approximately 70 per cent of Nigeria’s population live in rural areas, yet these areas are home to 80 per cent of poor people.The report, the first poverty index survey published by the statistics bureau since 2010, said that 65 per cent of the poor (86 million people) live in the North, while 35 per cent (nearly 47 million) live in the South.“Poverty levels across states vary significantly, with the incidence of multidimensional poverty ranging from a low of 27 per cent in Ondo to a high of 91 per cent in Sokoto,” it said.Nasiru, who does not have a university degree and has been rejected for many jobs, no longer tries to get work.He hasn’t tried to get a job in five years. Instead, his family depends on his wife’s meagre income from her sewing business.Donors also visit the community and donate money and food to families. So, Nasiru’s family, just like any other family in the community, depends largely on the generosity of these donor churches and NGOs.But last year, Nasiru and his family fell on seriously hard times.Donations to the community were not frequent, and Nasiru could not do anything to provide for his family except pray that donors will once again show up for them as they have always done.

Appendix B.2. Individual Responsibility + Internal View Condition

- By Jared ShuaibuThu, 26 Jan 2023 13:07:20 WATThe number of Nigerians living in poverty stands at over 133 million, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced Thursday. It said the figure represents 63 per cent of the nation’s population.The NBS disclosed this in its “Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index” released on Thursday. According to the report, over half of the population who are poor cook with dung, wood or charcoal, rather than cleaner energy.It said high deprivations are also apparent in sanitation, time to healthcare, food insecurity, and housing.“The figures are not surprising,” said Suleiman Nasiru who lives in Makoko, one of Lagos’s notorious slums.Just like many residents of Makoko, Nasiru’s family does not have access to clean water.“The black water from the lagoon, that’s what we use to wash clothes and do house chores. Sometimes, we even drink it because we cannot afford to buy clean water,” Nasiru said.He has six children, and none of them go to school because Nasiru does not work and can’t afford the school fees. He has given up on trying to get a job and instead spends most of his time at home, doing nothing.The NBS noted that multidimensional poverty is higher in rural areas, where 72 per cent of people are poor, compared to 42 per cent of people in urban areas.According to the report, approximately 70 per cent of Nigeria’s population live in rural areas, yet these areas are home to 80 per cent of poor people.The report, the first poverty index survey published by the statistics bureau since 2010, said that 65 per cent of the poor (86 million people) live in the North, while 35 per cent (nearly 47 million) live in the South.“Poverty levels across states vary significantly, with the incidence of multidimensional poverty ranging from a low of 27 per cent in Ondo to a high of 91 per cent in Sokoto,” it said.Nasiru, who does not have a university degree and has been rejected for many jobs, no longer tries to get work. He hasn’t tried to get a job in five years because he doesn’t believe there’s anything else he can do.“No matter what I try, it doesn’t work,” Nasiru said. “I stopped trying. I am tired.”His family depends on his wife’s meagre income from her sewing business. But a substantial part of his livelihood comes from money from donors who visit the community and donate money and food to families.“Churches and NGOs, they come and give us money,” Nasiru said. “If not for them, what will we do?”But last year, Nasiru and his family fell on seriously hard times. Donations to the community were not frequent, and Nasiru could not do anything to provide for his family.“I just knelt down and prayed that God will bring them back because I don’t know what else to do. And God answered,” Nasiru said.

Appendix B.3. Social Responsibility + External View Condition

- By Jared ShuaibuThu, 26 Jan 2023 13:07:20 WATThe number of Nigerians living in poverty stands at over 133 million, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced Thursday. It said the figure represents 63 per cent of the nation’s population.The NBS disclosed this in its “Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index” released on Thursday. According to the report, over half of the population who are poor cook with dung, wood or charcoal, rather than cleaner energy.It said high deprivations are also apparent in sanitation, time to healthcare, food insecurity, and housing.For someone like Suleiman Nasiru who lives in Makoko, one of Lagos’s notorious slums, the figures are not surprising.Just like many residents of Makoko, Nasiru’s family does not have access to clean water. They use contaminated black water from the lagoon to wash their clothes and do house chores. They sometimes drink this water when they cannot afford to buy clean water.Nasiru has three children. None of them go to school because Nasiru can’t afford the fees. Instead, the children help out at home or play with other children during school time.The lack of critical policy intervention to address multidimensional poverty has real consequences for Nasiru and his family and other people like them who mostly live in Nigeria’s rural areas.The NBS noted that multidimensional poverty is higher in rural areas, where 72 per cent of people are poor, compared to 42 per cent of people in urban areas.According to the report, approximately 70 per cent of Nigeria’s population live in rural areas, yet these areas are home to 80 per cent of poor people.The report, the first poverty index survey published by the statistics bureau since 2010, said that 65 per cent of the poor (86 million people) live in the North, while 35 per cent (nearly 47 million) live in the South.“Poverty levels across states vary significantly, with the incidence of multidimensional poverty ranging from a low of 27 per cent in Ondo to a high of 91 per cent in Sokoto,” it said.Unemployment and inflation are also big issues. According to Bloomberg, one in three Nigerians are jobless.Nasiru has tried to get a job for many years without luck. Now, his family depends on his wife’s sewing and on donations to the Makoko community.High inflation rates in the country have also hit the family hard. They can no longer buy things they once could previously afford.Without strong government policies to tackle multidimensional poverty, and without intervention from Nigeria’s elites, people like Nasiru and his family will continue to be vulnerable to adversity.

Appendix B.4. Social Responsibility + Internal View Condition

- By Jared ShuaibuThu, 26 Jan 2023 13:07:20 WATThe number of Nigerians living in poverty stands at over 133 million, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced Thursday. It said the figure represents 63 per cent of the nation’s population.The NBS disclosed this in its “Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index’’ released on Thursday. According to the report, over half of the population who are poor cook with dung, wood or charcoal, rather than cleaner energy.It said high deprivations are also apparent in sanitation, time to healthcare, food insecurity, and housing.“The figures are not surprising,” said Suleiman Nasiru who lives in Makoko, one of Lagos’s notorious slums.Just like many residents of Makoko, Nasiru’s family does not have access to clean water.“The black water from the lagoon, that’s what we use to wash clothes and do house chores. Sometimes, we even drink it because we cannot afford to buy clean water,” Nasiru said.Nasiru has three children, and none of them go to school because Nasiru can’t afford the fees. Instead, the children help out at home or play with other children during school time.“It’s the government, the politicians,” Nasiru said. “They make everything hard for the ordinary man. They want to keep those of us here below them.”The NBS noted that multidimensional poverty is higher in rural areas, where 72 per cent of people are poor, compared to 42 per cent of people in urban areas.According to the report, approximately 70 per cent of Nigeria’s population live in rural areas, yet these areas are home to 80 per cent of poor people.The report, the first poverty index survey published by the statistics bureau since 2010, said that 65 per cent of the poor (86 million people) live in the North, while 35 per cent (nearly 47 million) live in the South.“Poverty levels across states vary significantly, with the incidence of multidimensional poverty ranging from a low of 27 per cent in Ondo to a high of 91 per cent in Sokoto,” it said.Nasiru says unemployment and inflation are also big issues.“I’ve tried to apply for a job for so many years,” Nasiru said. “They tell me I’m not qualified. So, how am I supposed to feed my family?”Nasiru can no longer buy some of the things he was able to afford just a few years ago, and now his family depends on income from his wife’s sewing and on donations to the Makoko community.“But that’s not enough,” Nasiru said. “That doesn’t even feed the family every day.”Nasiru believes the solution to multidimensional poverty lies in critical policy intervention in education, health, housing, food insecurity, and other basic needs.“But the problem is that the government and elite don’t care about us. They don’t have any plans for us, and no matter how hard we try to survive, they will continue to push us down.”

Appendix B.5. No Exemplar Condition

- By Jared ShuaibuThu, 26 Jan 2023 13:07:20 WATThe number of Nigerians living in poverty stands at over 133 million, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced Thursday. It said the figure represents 63 per cent of the nation’s population.The NBS disclosed this in its “Nigeria Multidimensional Poverty Index” released on Thursday.According to the report, over half of the population who are poor cook with dung, wood or charcoal, rather than cleaner energy.It said high deprivations are also apparent in sanitation, time to healthcare, food insecurity, and housing.The NBS noted that multidimensional poverty is higher in rural areas, where 72 per cent of people are poor, compared to 42 per cent of people in urban areas.According to the report, approximately 70 per cent of Nigeria’s population live in rural areas, yet these areas are home to 80 per cent of poor people.The report, the first poverty index survey published by the statistics bureau since 2010, said that 65 per cent of the poor (86 million people) live in the North, while 35 per cent (nearly 47 million) live in the South.“Poverty levels across states vary significantly, with the incidence of multidimensional poverty ranging from a low of 27 per cent in Ondo to a high of 91 per cent in Sokoto,” it said.Similarly, the report said the poorest states are Sokoto, Bayelsa, Jigawa, Kebbi, Gombe, and Yobe, but we could not say for sure which of these is the poorest, because their confidence intervals overlap.In general, the NBS said the incidence of monetary poverty is lower than the incidence of multidimensional poverty across most states.“In Nigeria, 40.1 per cent of people were poor, based on the 2018/19 national monetary poverty line, and 63 per cent are multidimensionally poor according to the National MPI 2022,” it said.

Appendix B.6. Not About Poverty

- By Daily TrustWed, 17 May 2023 8:24:29 WATUS Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, has phoned President-elect Bola Tinubu, pledging the commitment of his country to Nigeria’s democracy.Mathew Miller, a spokesman for the US government, disclosed this in a statement.“Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken spoke this morning with Nigerian President-elect Bola Ahmed Tinubu to emphasize his continued commitment to further strengthening the U.S.-Nigeria relationship with the incoming administration.”“The Secretary noted that the U.S.-Nigeria partnership is built on shared interests and strong people-to-people ties and that those links should continue to strengthen under President-elect Tinubu’s tenure. Secretary Blinken and President-elect Tinubu discussed the importance of inclusive leadership that represents all Nigerians, continued comprehensive security cooperation, and reforms to support economic growth.”According to Tunde Rahman, spokesman of the president-elect, the conversation was initiated by the US diplomat.“The telephone discussion, which was frank and friendly, took place on Tuesday evening,” Rahman said in a statement.“While affirming his democratic bona fides, President-elect Tinubu expressed his absolute belief that the result of the elections, which he clearly won, reflected the will of the Nigerian people.“He said he would work to unite the country and ensure that Nigerians are happy and enjoy the benefits of democracy and progressive good governance.”Rahman quoted Blinken to have told the President-elect that without national unity, security, economic development and good governance, Nigeria would not become a better place to live in or play her proper role in the comity of African nations.“Secretary Blinken assured that Nigeria should expect a good and mutually-beneficial relationship with the US.”“He promised to play his part in bringing a sustained and cordial relationship between the two nations to fruition, saying a democratic and peaceful Nigeria is important to the United States as it is to Africa.”Tinubu is currently in Europe.

Appendix C. Linear Regression Models Testing Effects of Exemplar Condition on Perceptions of Poverty

| Poverty Issue Significance | Social Responsibility to Address Poverty | |||||

| Controls, Experimental Condition | Beta | t | p Value | Beta | t | p Value |

| Age | −0.03 | −0.61 | 0.54 | 0.15 | 3.20 | 0.001 |

| Social Class | −0.15 | −3.26 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.64 |

| Male gender, vs. female gender | −0.07 | −1.51 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 1.95 | 0.05 |

| Exemplar, vs. no exemplar | −0.48 | −0.48 | 0.63 | −0.09 | −1.84 | 0.06 |

| F test, adjusted R2 | F(4,462) = 3.70, p = 0.006 adjusted r2 = 0.02 | F(4,460) = 4.58, p = 0.001, adjusted r2 = 0.03 | ||||

Appendix D. Linear Regression Models Testing Effects of Exemplar Condition on Identification with People Living in Poverty

| Identification with People Living in Poverty | |||

| Controls, Experimental Condition | Beta | t | p Value |

| Age | −0.04 | −0.83 | 0.41 |

| Social Class | −0.05 | −1.01 | 0.31 |

| Male gender, vs. female gender | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.73 |

| Exemplar, vs. no exemplar | 0.14 | 3.09 | 0.002 |

| F test, adjusted R2 | F(4,458) = 2.62, p = 0.03 adjusted r2 = 0.02 | ||

| 1 | An additional message manipulation, exemplar point of view (first person or third person), is not included in the analysis, in the interest of space. Exemplar point of view was not significantly related to any outcome variables or to the mediating variable; and there were no interaction effects for exemplar point of view and the other independent variable (individual vs. social responsibility). Results of exemplar point of view analysis are available from the corresponding author. |

| 2 | To control for alternative explanations for variations in identification with exemplars, we tested the relationship between demographic variables and identification. Gender, age, social class, education, or hours spent with news per week had no significant association with identification. |

References

- Akinola, O. A., Omar, B., & Mustapha, L. K. (2022). Corruption in the limelight: The relative influence of traditional mainstream and social media on political trust in Nigeria. International Journal of Communication, 16, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Amah, M., & Young, R. (2023, August 7–10). Getting to the heart of the matter: Journalistic use of exemplars to represent poverty in Nigeria [Conference presentation]. 106th Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC), Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Arise News. (2024, December 22). Stampede deaths: Hunger in Nigeria is self imposed, leaders have reduced us to beggars—Prof. Yusuf [Video]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aATtmi7G1E8 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Banjo, O. O., & Umunna, D. (2022). American media, American mind: Media impact on Nigerians’ perceptions. International Journal of Communication, 16, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bigsby, E., Bigman, C. A., & Martinez Gonzalez, A. (2019). Exemplification theory: A review and meta-analysis of exemplar messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 43(4), 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, H.-B., & Bathelt, A. (1994). The utility of exemplars in persuasive communications. Communication Research, 21, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H., & Salmon, C. T. (2007). Unintended effects of health communication campaigns. Journal of Communication, 57(2), 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (2001). Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Communication & Society, 4(3), 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, G. N. (2016). Negative affect as a mechanism of exemplification effects: An experiment on two-sided risk argument recall and risk perception. Communication Research, 43(6), 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M. J., & Pal, M. (2020). Theorizing from the global south: Dismantling, resisting, and transforming communication theory. Communication Theory, 30(4), 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R., & Zillmann, D. (1994). Exaggerated versus representative exemplification in news reports: Perception of issues and personal consequences. Communication Research, 21, 603–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., & Knies, E. (2017). Validating a scale for citizen trust in government organizations. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(3), 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnant, A., Len-Ríos, M. E., & Young, R. (2013). Journalistic use of exemplars to humanize health news. Journalism Studies, 14(4), 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, M. R., & Littau, J. (2022). From political to personal: Tracking the use of exemplars in newspaper coverage of the affordable care act. Journalism Practice, 16(1), 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, R., & Wadhwa, D. (2019, January 9). Half of the world’s poor live in just 5 countries. World Bank. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/half-world-s-poor-live-just-5-countries (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Kim, H. S., Bigman, C. A., Leader, A. E., Lerman, C., & Cappella, J. N. (2012). Narrative health communication and behavior change: The influence of exemplars in the news on intention to quit smoking. Journal of Communication, 62(3), 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M. (2021). Exemplifying power matters: The impact of power exemplification of transgender people in the news on issue attribution, dehumanization, and aggression tendencies. Journalism Practice, 17, 525–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Ocando, J. (2015). Blaming the victim: How global journalism fails those in poverty. Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z., Ma, R., & Ledford, V. (2023). Is my story better than his story? Understanding the effects and mechanisms of narrative point of view in the opioid context. Health Communication, 38(9), 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabweazara, H. M. (2018). Newsmaking cultures in Africa: Normative trends in the dynamics of socio-political & economic struggles. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer-Gusé, E. (2007). Entertainment television and safe sex: Understanding effects and overcoming resistance. University of California, Santa Barbara. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, L. (2022). Introduction: Journalism studies and the global south-theory, practice and pedagogy. Journalism Studies, 23(13), 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2022, November 17). Nigeria launches its most extensive national measure of multidimensional poverty. Available online: https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/news/78 (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Oatley, K. (1999). Meetings of minds: Dialogue, sympathy, and identification, in reading fiction. Poetics, 26(5–6), 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. B., Dillard, J. P., Bae, K., & Tamul, D. J. (2012). The effect of narrative news format on empathy for stigmatized groups. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 89(2), 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Oschatz, C., Emde-Lachmund, K., & Klimmt, C. (2021). The persuasive effect of journalistic storytelling: Experiments on the portrayal of exemplars in the news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 98(2), 407–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasubramanian, S., & Banjo, O. O. (2020). Critical media effects framework: Bridging critical cultural communication and media effects through power, intersectionality, context, and agency. Journal of Communication, 70(3), 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, P., Tankard, J. W., Jr., & Lasorsa, D. (2004). How to build social science theories. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck, J., Tsfati, Y., Boomgaarden, H., Damstra, A., Lindgren, E., Vliegenthart, R., & Lindholm, T. (2020). News media trust and its impact on media use: Toward a framework for future research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 44(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal-Or, N., & Cohen, J. (2010). Understanding audience involvement: Conceptualizing and manipulating identification and transportation. Poetics, 38(4), 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukachinsky, R., Mastro, D., & King, A. (2011). Is a picture worth a thousand words? The effect of race-related visual and verbal exemplars on attitudes and support for social policies. Mass Communication & Society, 14, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Krieken, K., Hoeken, H., & Sanders, J. (2015). From reader to mediated witness: The engaging effects of journalistic crime narratives. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(3), 580–596. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, A. (2020). Evoking empathy or enacting solidarity with marginalized communities? A case study of journalistic humanizing techniques in the San Francisco homeless project. Journalism Studies, 21(12), 1705–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbord, S. (2022). What is next for de-westernizing communication studies? Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 17(1), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. (1993). On sin versus sickness: A theory of perceived responsibility and social motivation. American Psychologist, 48(9), 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D. (2020). Victims and voices: Journalistic sourcing practices and the use of private citizens in online healthcare-system news. Journalism Studies, 21(8), 1017–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R., Chen, L., Zhu, G., & Subramanian, R. (2021). Cautionary tales: Social representation of risk in US newspaper coverage of cyberbullying exemplars. Journalism Studies, 22(13), 1832–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillmann, D. (1999). Exemplification theory: Judging the whole by some of its parts. Media Psychology, 1, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillmann, D. (2006). Exemplification effects in the promotion of safety and health. Journal of Communication, 56, S221–S237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | Median (Range) or % |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 27 (18–68) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 56.6% |

| Female | 43.1% |

| Other | 0.4% |

| Region | |

| North Central | 20.0% |

| North East | 1.0% |

| North West | 8.4% |

| South East | 12.7% |

| South South | 13.1% |

| South West | 44.8% |

| Highest Level of Education | |

| Primary or Secondary school | 11.4% |

| Post-secondary school vocational training | 6.5% |

| OND/HND | 13.1% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 51.9% |

| Postgraduate diploma or higher | 17.1% |

| Social Class | |

| Poor | 2.3% |

| Lower middle class | 56.9% |

| Upper middle class or affluent | 40.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amah, M.; Young, R. De-Westernizing Media and Communication Theory in Practice: Toward a More Inclusive Theory for Explaining Exemplification Phenomena. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020090

Amah M, Young R. De-Westernizing Media and Communication Theory in Practice: Toward a More Inclusive Theory for Explaining Exemplification Phenomena. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(2):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020090

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmah, Munachim, and Rachel Young. 2025. "De-Westernizing Media and Communication Theory in Practice: Toward a More Inclusive Theory for Explaining Exemplification Phenomena" Journalism and Media 6, no. 2: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020090

APA StyleAmah, M., & Young, R. (2025). De-Westernizing Media and Communication Theory in Practice: Toward a More Inclusive Theory for Explaining Exemplification Phenomena. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020090