Against-Hegemonic Agenda: Indigenous New Media and the Challenge to Hegemonic Power

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Research Problem, Objectives and Hypotheses

1.2. From Resistance to Offensive Strategy: Genealogy of a Movement

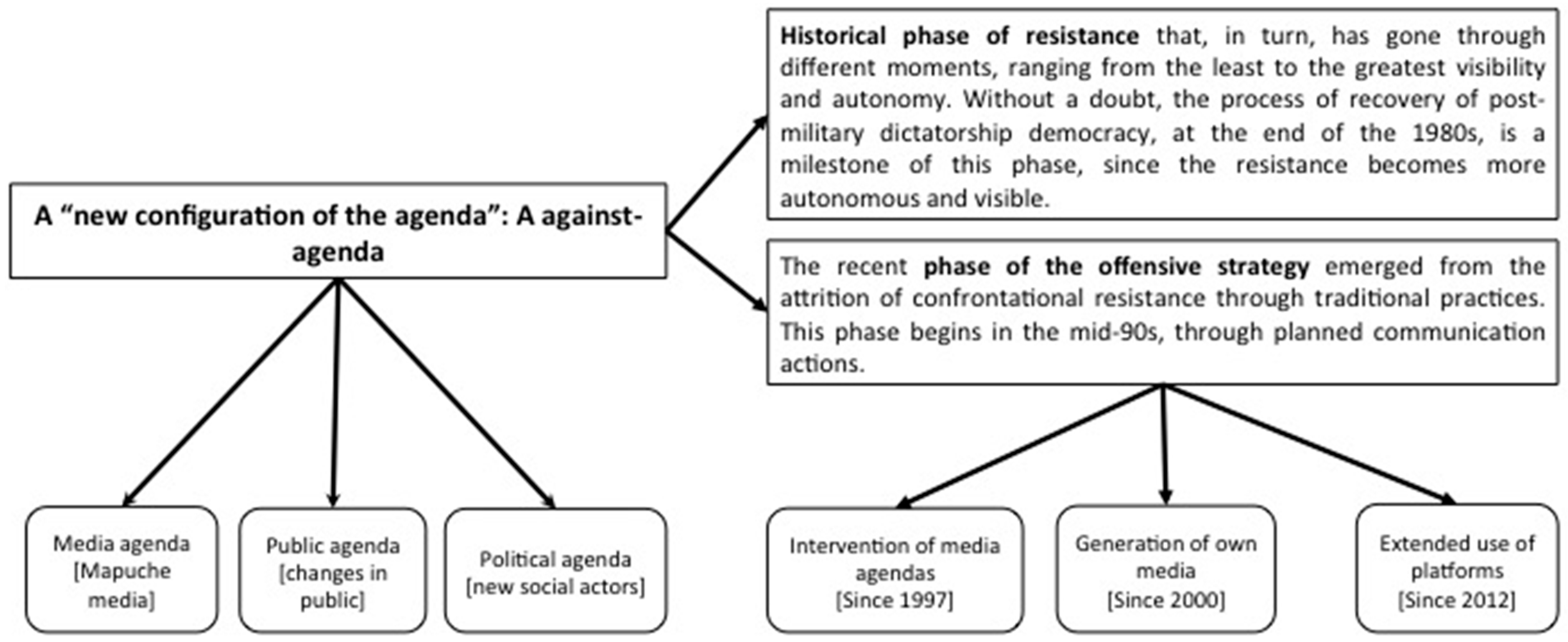

1.3. Against-Hegemonic Agenda

1.4. New Agendas and Social Movements

1.5. The Dispute for the Agenda

1.6. The Importance of Networking

1.7. The Role of New Media in Socio-Political Contexts

1.8. Production of the Emergent

1.9. Collective Production of Language

2. Methodology

Materials and Methods

- (a)

- A total of 1034 news items were analyzed, according to the following inclusion/exclusion criteria:

- (i)

- News items whose contents refer to issues related to the native peoples of Argentina and Chile, especially the Mapuche people of both countries.

- (ii)

- News items, news pieces, or opinion pieces in which the Mapuche people appear as protagonists or are directly affected by an event that involves them.

- (iii)

- That represent the main hegemonic media with national coverage in Argentina and Chile.

- (iv)

- That represent the most important hegemonic media with regional coverage in Argentina and Chile, in the three cities included in the project (Temuco and Valdivia, in the south of Chile, and La Plata in Argentina).

- (v)

- That represent against-hegemonic media in Argentina and Chile, considering the presence of Mapuche issues.

- (vi)

- News that corresponded to the period between 1 November 2018 and 31 October 2019 (Table 1).

- (b)

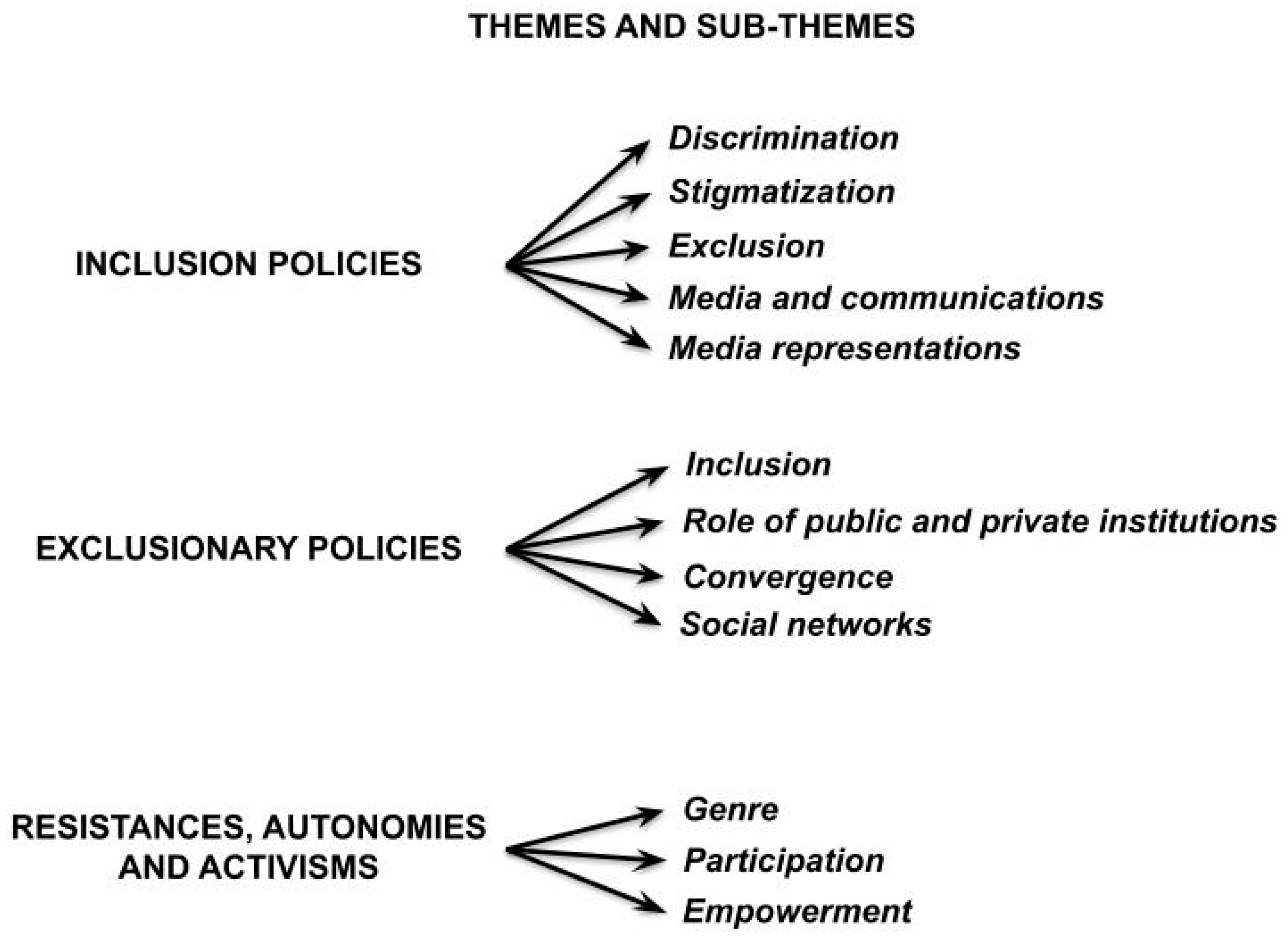

- Twenty in-depth interviews with Mapuche Indigenous leaders from Chile (20 subjects) and Argentina (1 subject), using 3 thematic cores and 12 sub-themes. Here, we understand Mapuche leaders to be those who are recognized in different areas, such as academia, politics, or in their performance in the public or private sector. This was ensured by using the “snowball” technique in the conformation of the group of interviewees; that is, the first interviewees gave references to the names of the following, based on the characteristics recorded (Table 2). Interviews were conducted between 2 April 2020 and 29 August 2022, taking into consideration the difficulties that arose as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the time required to coordinate each interview with Mapuche people with different characteristics (Figure 1). This part of the study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the University of La Frontera (on 11 December 2020, as recorded in Act Number 061_19, Folio No043_19). Thus, the interviews have been signed by each interviewee, who has kept a copy. The consents have been archived in a duly safeguarded place at the University, while the recordings of the interviews as well as the transcriptions are duly safeguarded. To ensure anonymity, both in the presentation of the data and in any publication thereof, only a description characterized by generic coded aspects has been used, namely gender (male/female), age (young/adult), activity (academic/political/professional), and country and city of origin, such that it is not possible to associate the responses with specific people.

- (c)

- Review and document the analysis of historical texts of the Indigenous movement.

- (a)

- Texts of different nature, such as books, chronicles, or news;

- (b)

- That provide information about the Mapuche movement;

- (c)

- That provide information on the Mapuche media.

3. Results

3.1. Strategies Identified

3.1.1. Intervention of Hegemonic Agendas

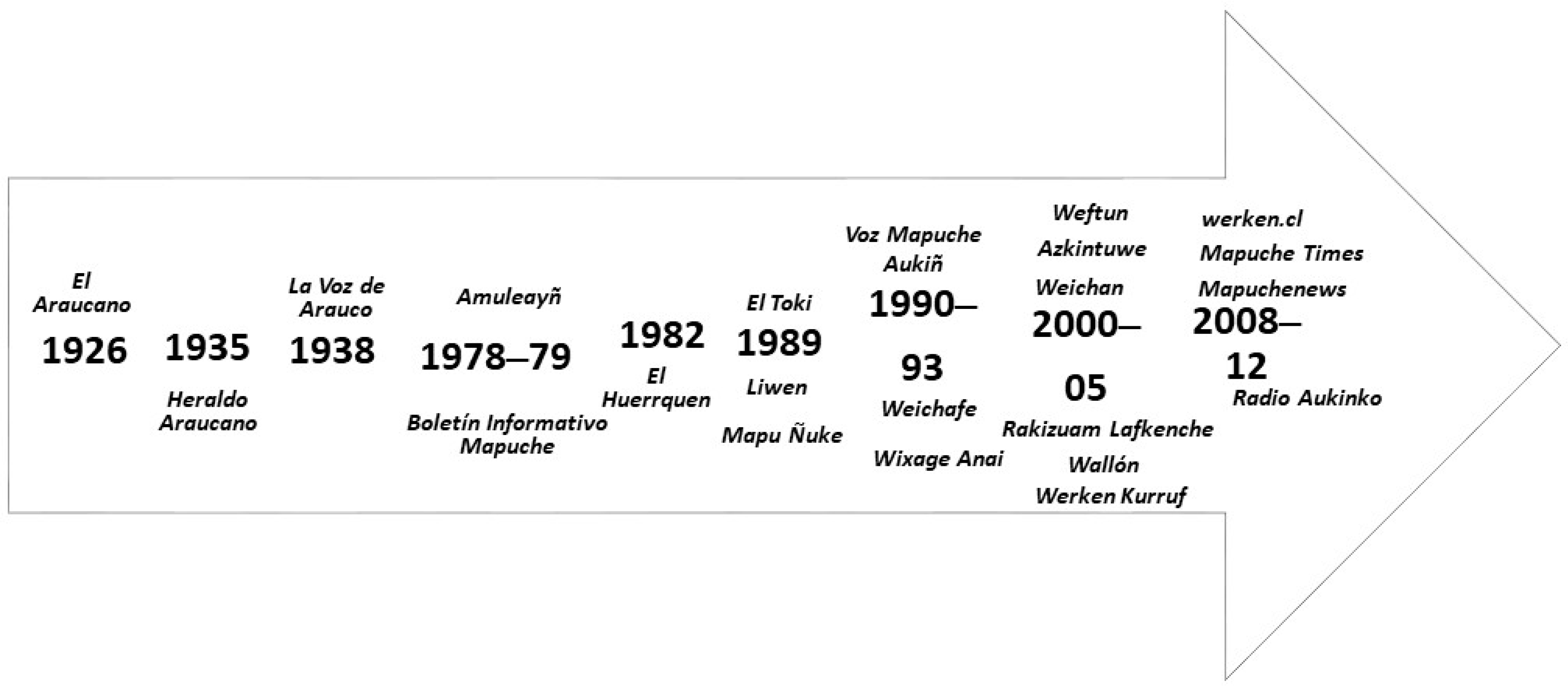

3.1.2. Creating New Media to Build a Media Against-Agenda

- (a)

- “The first thing the hegemonic media do is stigmatize the Mapuche, they call us terrorists. They always put the Wichís on the agenda when they die of hunger or they put the indigenous peoples on the agenda when there is some repression, some roadblock, some death” (E 20).

- (a)

- Allows the active incorporation of new actors: “incorporate Mapuche youth into these processes.” (E 3).

- (b)

- It allows for dissemination, validation, and cohesion: “establishing communication justice, equating Mapuche presence in the Chilean collective imagination” (E 4).

- (c)

- It allows us to inform and achieve unity: “which allows us to be united and active, despite the multiple adversities, which are triggered from time to time because this living resistance is latent, in a silent network” (E 2).

- (d)

- Allows you to think differently: “Without independent media, it would be impossible to think differently” (E 8).

- (e)

- It allows for incorporating new allies and transmitting hope: “The multiple voices from different places can awaken hope in those who are fainting or reinforce the conviction of those who remain fighting, finding allies who fight on other rivers” (E 6).

- (f)

- It allows access to the diversity of perspectives: “When this type of communication did not exist, you could only find out about alternative initiatives and/or resistance if the traditional media were interested in this type of news or if someone traveled and acted as nexus […] allow access to views of the most diverse facts; which has been fundamental when there is a policy of demonization of the resistance movement” (E 6).

3.2. Characterization of the Against-Agenda

- It is another agenda built within the framework of a dispute for control of the semiotic-communicational code that gives meaning to society, its relationships, and especially, its possible transformations.

- In the same sense, the against-agenda is a model that explains the role of the new media.

- The against-agenda is only built in very particular socio-political situations.

- The against-agenda is an emergency, since counter-agenda setting operates through emergent actors, in emergent contexts and through emergent media.

- Finally, the against-agenda is configured through collective and community work that mobilizes in a utopian dimension.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abela, J. A. (2012). La descodificación de la agenda: Un modelo analítico para el conocimiento manifiesto y latente de la agenda pública. Intangible Capital, 8(3), 520–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, M., & Cárdenas, C. (2021). Convocatoria de protesta a través de Instagram, un análisis socio cognitivo de estrategias discursivas en el contexto del movimiento social en Chile (2019–2020). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 79, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancán, J., & Calfío, M. 1998 November 9–13. El retomo al País mapuche. Reflexiones preliminares para una utopía por construir. III Congreso Chileno de Antropología. [Google Scholar]

- Ardèvol-Abreu, A., Gil de Zúñiga, H., & McCombs, M. E. (2020). Orígenes y desarrollo de la teoría de la agenda setting en Comunicación. Tendencias en España (2014–2019). Profesional de la información, 29(4), e290414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruguete, N. (2016). El poder de la agenda. Política, medios y público. Biblos. [Google Scholar]

- Aruguete, N. (2017). Agenda building. Revisión de la literatura sobre el proceso de construcción de la agenda mediática. Signo y Pensamiento, 70(XXXVI), 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamblea de Caciques del Sur & Dirigentes de Indios. (1961). Acuerdos de la Asamblea de Caciques del Sur y Dirigentes de Indios celebrado en Osorno los días 31 de marzo, 1 y 2 de abril de 1961, Osorno, 2 de abril de 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, M., Codina, L., & Salaverría, R. (2019). Qué son y qué no son los nuevos medios. 70 visiones de expertos hispanos. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 74, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candón, J. (2012). La batalla de la agenda: De las redes sociales a la agenda mediática, política y electoral. TecCom Studies: Estudios de Tecnología y Comunicación, 4, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Carrero, V., Soriano, R., & Trinidad, A. (2006). Teoría fundamentada—Grounded theory. La construcción de la teoría a través del análisis interpretacional. CIS (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas). [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Estudios & Documentación Mapuche Liwen. (1990, March 27–29). Cuestión mapuche, descentralización del Estado y autonomía regional. Seminario Utopía indígena, Colonialismo y Evangelización, Santiago de Chile, Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Charron, J. (1998). Los medios y las fuentes. Los límites al modelo de la agenda setting. In G. Gauthier, A. Gosselin, & J. Mouchon (Eds.), Comunicación y política (pp. 72–93). Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Organizadora del Primer Congreso del Movimiento Netuaiñ Mapu. (1972, February). Malleco y Cautín.

- Dearing, J. W., & Rogers, E. M. (1992). Communication concepts 6: AgendaSming. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, C. (2022a). Contra-Agenda. La disputa por la agenda política y mediática. Tirant lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, C. (2022b). L’ennemi. Production, médiatisation et globalisation. Ediciones L’ Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, C. (2022c). Making enemies: The cultural industry and the new enemisation modes. In C. Del Valle, & F. Sierra (Eds.), Communicology of the south. Critical perspectives from Latin America. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, C. (2023). From hegemonic colonial cultural rhetoric to against-hegemonic decolonial cultural rhetoric in the representations of the indigenous in America. In V. Luarsabishvili (Ed.), Cultural rhetoric. Rhetorical perspectives, transferential insights. New Vision University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle, C. (2024). Genealogy of the indigenous as an enemy: Criticism of moral, criminal, and neoliberal reason in Chile. In S. Roy (Ed.), Encyclopedia of race, ethnicity, and communication (pp. 1–19). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El Diario Austral. (1938, November 13). Sociedades araucanas formaron una corporación en esta ciudad. El Diario Austral. [Google Scholar]

- García. (2014). Persiguiendo la utopia. Medios de comunicación Mapuche y la construcción de la utopía del Wallmapu. Anuario de Acción Humanitaria y Derechos Humanos, 12, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, T. (1986). Convertir a los movimientos de protesta en temas periodísticos. In D. Graber (Ed.), El poder de los medios en la política. Grupo Editor Latinoamericano. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L., Vu, H., & McCombs, M. (2012). An expanded perspective on agenda-setting effects. Exploring the third level of agenda setting. Revista de Comunicación, 11, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, F. (2014). We Aukiñ Zugu. Historia de los medios de comunicación mapuche. Editorial Quimantú. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas-INE. (2017). Resultados CENSO 2017. Recuperado de la base de datos del INE. [Google Scholar]

- La Época. (1910a, July 5). Los Araucanos en el Centenario. La Época, II(452). [Google Scholar]

- La Época. (1910b, July 20). Sociedad Caupolicán Defensora de la Araucanía. La Época, II(465). [Google Scholar]

- La Época. (1910c, December 14). Sociedad Caupolicán: Acta de la Sesión del 11 del presente. La Época, II(586). [Google Scholar]

- Lang, G., & Lang, K. (1981). Watergate: An exploration of the agenda-building process. In G. Cleveland (Ed.), Mass communication review yearbook (pp. 447–468). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lippman. (1922). Public Opinion. Harcourt, Brace and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Marimán. (2011). Mapuexpress. Informativo Mapuche. Rakizuam Tañi Wallmapu. Fundación Green Grand Fund. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M. (2012). Civic osmosis: The social impact of media. Comunicación y Sociedad, XXV(1), 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). Agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosco, V. (2009). La economía política de la comunicación. Reformulación y renovación. Editorial Bosch. [Google Scholar]

- Muleiro, H. (2006). Al margen de la agenda. Noticias, discriminación y exclusión. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Obregón, R., & Tufte, T. (2017). Communication, social movements, and collective action: Toward a new research agenda in communication for development and social change. Journal of Communication, 67, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, G. (1998). De las mediaciones a los medios. Contribuciones de la obra de Martín-Barbero al estudio de los medios y sus procesos de recepción. In M. Laverde, & R. Reguillo (Eds.), Mapas Nocturnos. Diálogos con la obra de Jesús Martín Barbero (pp. 91–101). Siglo del Hombre Editores, Universidad Central—DIUC. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, G., & González, R. (2012). Una coartada metodológica. Abordajes cualitativos en la investigación en comunicación, medios y audiencias. Productora de Contenidos Culturales Sagahón Repoll. [Google Scholar]

- Pairicán, F., & Álvarez, R. (2011). La nueva guerra de Arauco: La coordinadora Arauco malleco en el Chile de la concertación de partidos por la democracia (1997–2009). Revista Izquierdas, 10, 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, P., Rodríguez, R., & Sáez, C. (2016). Movimiento estudiantil en Chile, aprendizaje situado y activismo digital. Compromiso, cambio social y usos tecnológicos adolescentes. OBETS. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 11(1), 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proclama de la Coordinadora de Resistencia Mapuche Pelentaro. (1986, June). Butahuillimapu.

- Roberts, D. (1972). The nature of communication effects. In W. Schramm, & D. Roberts (Eds.), The process and effects of mass-communications (p. 997). University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, H. (2012). Movimientos sociales y medios de comunicación. Poderes en tensión. Hallazgos, 9(18), 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, N., & Miranda, O. (2015). Dinámica sociopolítica del conflicto y la violencia en territorio mapuche. Particularidades históricas de un nuevo ciclo en las relaciones contenciosas. Revista de Sociología, 30, 33–69. [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra, J. (2023). Comunicación, medios y movimientos sociales en Chile, balance de (un cuarto de) siglo. Comunicación y medios, 32(48), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintout, F. (2018). Medios hegemónicos en América Latina: Cinco estrategias de disciplinamiento. In D. Bruzzone, M. Papaleo, A. M. Parducci, A. V. C. del Valle, R. Gómez, C. Villamayor, J. Acevedo, L. M. P. M. Villanueva, Á. E. D. Soto, E. V. Ouriques, O. Rincón, D. Badenes, M. L. Sánchez, L. González, J. Barba, R. Blasco, F. G. Germanier, A. A. Vargas, M. C. Escudero, . . . L. A. Barrios (Eds.), Comunicación para la resistencia: Conceptos, tensiones y estrategias en el campo político de los medios (pp. 13–20). CLACSO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sádaba, T. (2008). Framing: El encuadre de las noticias. El binomio terrorismo-medios. La Crujía. [Google Scholar]

- Scherman, A., Arriagada, A., & Valenzuela, S. (2014). Social media and protests in Chile. Politics, 35, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheafer, T., & Weimann, G. (2005). Agenda building, Agenda setting, priming, individual voting intentions, and the aggregate results: An analysis of four Israeli elections. Journal of Communication, 55(2), 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, F. (Ed.). (2021). Ciberactivismo y nuevos movimientos urbanos. La producción de la nueva ciudadanía digital. ACCI Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D., Graber, D., McCombs, M., & Eyal, C. (1981). Media Agenda setting in a presidential election: Issues, images and interest. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Youmans, W., & York, J. (2012). Social media and the activist toolkit: User agreements, corporate interests, and the information infrastructure of modern social movements. Journal of Communication, 6(2), 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-H. (1992). Issue competition and attention distraction: A zero-sum theory of Agenda-setting. Journalism Quarterly, 69(4), 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunino, E. (2018). Agenda setting: Cincuenta años de investigación en comunicación. Intersecciones en Comunicación, (12), 187–210. [Google Scholar]

| Media | Country | Media Type |

|---|---|---|

| El Mercurio | Chile | Hegemonic |

| La Tercera | Chile | Hegemonic |

| El Austral de Temuco | Chile | Hegemonic |

| El Austral de Valdivia | Chile | Hegemonic |

| Mapuexpress | Chile | Against-hegemonic |

| El Mostrador | Chile | Against-hegemonic |

| Clarín | Argentina | Hegemonic |

| El Día | Argentina | Hegemonic |

| Página/12 | Argentina | Against-hegemonic |

| Portal 221 | Argentina | Against-hegemonic |

| Interviewee ID or Code | Sex | Age Group | Profession | City, Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E 1 | Man | Adult | Academic | Temuco, Chile |

| E 2 | Woman | Adult | Academic | |

| E 3 | Man | Adult | Political leader | |

| E 4 | Woman | Adult | Political leader | |

| E 5 | Man | Young | Public sector | |

| E 6 | Woman | Young | Public sector | |

| E 7 | Woman | Young | Private sector | |

| E 8 | Man | Young | Private sector | |

| E 9 | Man | Young | Activist | |

| E 10 | Woman | Young | Activist | |

| E 11 | Woman | Young | Academic | Valdivia, Chile |

| E 12 | Man | Adult | Activist | |

| E 13 | Woman | Young | Academic | |

| E 14 | Man | Young | Private sector | |

| E 15 | Woman | Adult | Public sector | |

| E 16 | Man | Adult | Private sector | |

| E 17 | Woman | Adult | Private sector | |

| E 18 | Man | Young | Academic | |

| E 19 | Woman | Adult | Political leader | |

| E 20 | Man | Adult | Political leader | La Plata, Argentina |

| Since 1997 (Arson Attacks) | Since 2019 (Social Outbreak) |

|---|---|

| Installation of a more planned media narrative, with very clear justification speeches; belligerent discourse | More consolidated speech, with a clear conceptual basis; unifying speech |

| There are no means and there is the discourse of a story that one wants to establish | Greater discursive control, with the positioning of content (wallmapu) and places (constituent convention), allows for greater strengthening of the discourse |

| Context of intervention of hegemonic agendas | Context of creating own media |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

del Valle-Rojas, C. Against-Hegemonic Agenda: Indigenous New Media and the Challenge to Hegemonic Power. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010025

del Valle-Rojas C. Against-Hegemonic Agenda: Indigenous New Media and the Challenge to Hegemonic Power. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010025

Chicago/Turabian Styledel Valle-Rojas, Carlos. 2025. "Against-Hegemonic Agenda: Indigenous New Media and the Challenge to Hegemonic Power" Journalism and Media 6, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010025

APA Styledel Valle-Rojas, C. (2025). Against-Hegemonic Agenda: Indigenous New Media and the Challenge to Hegemonic Power. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6010025