“News Desertification” in Europe: Highlighting Correlations for Future Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

Analysis of the LM4D Report Indicators

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. The Relationship between PSM and News Deserts

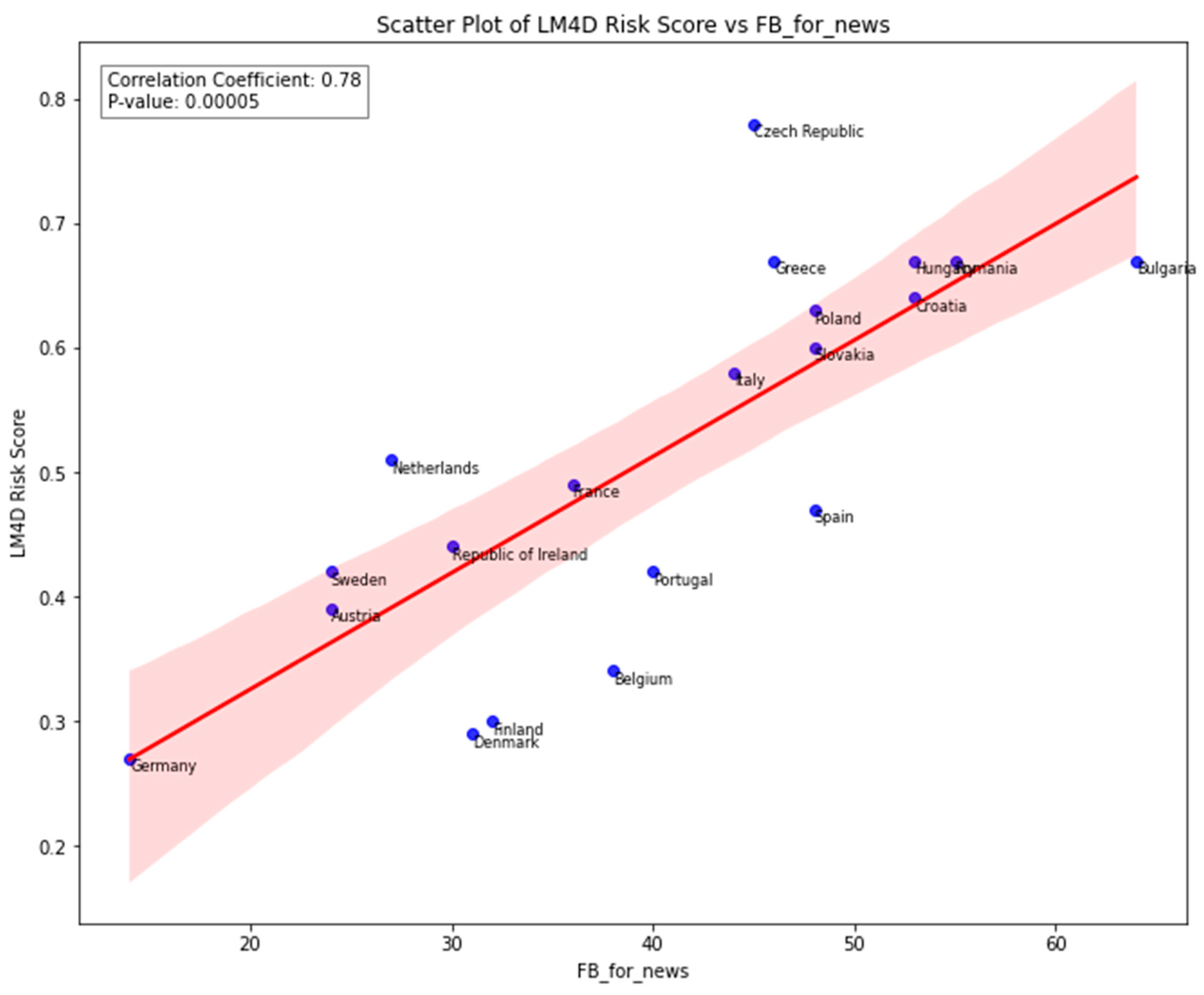

3.2. The Relationship between Social Media Usage and News Desertification

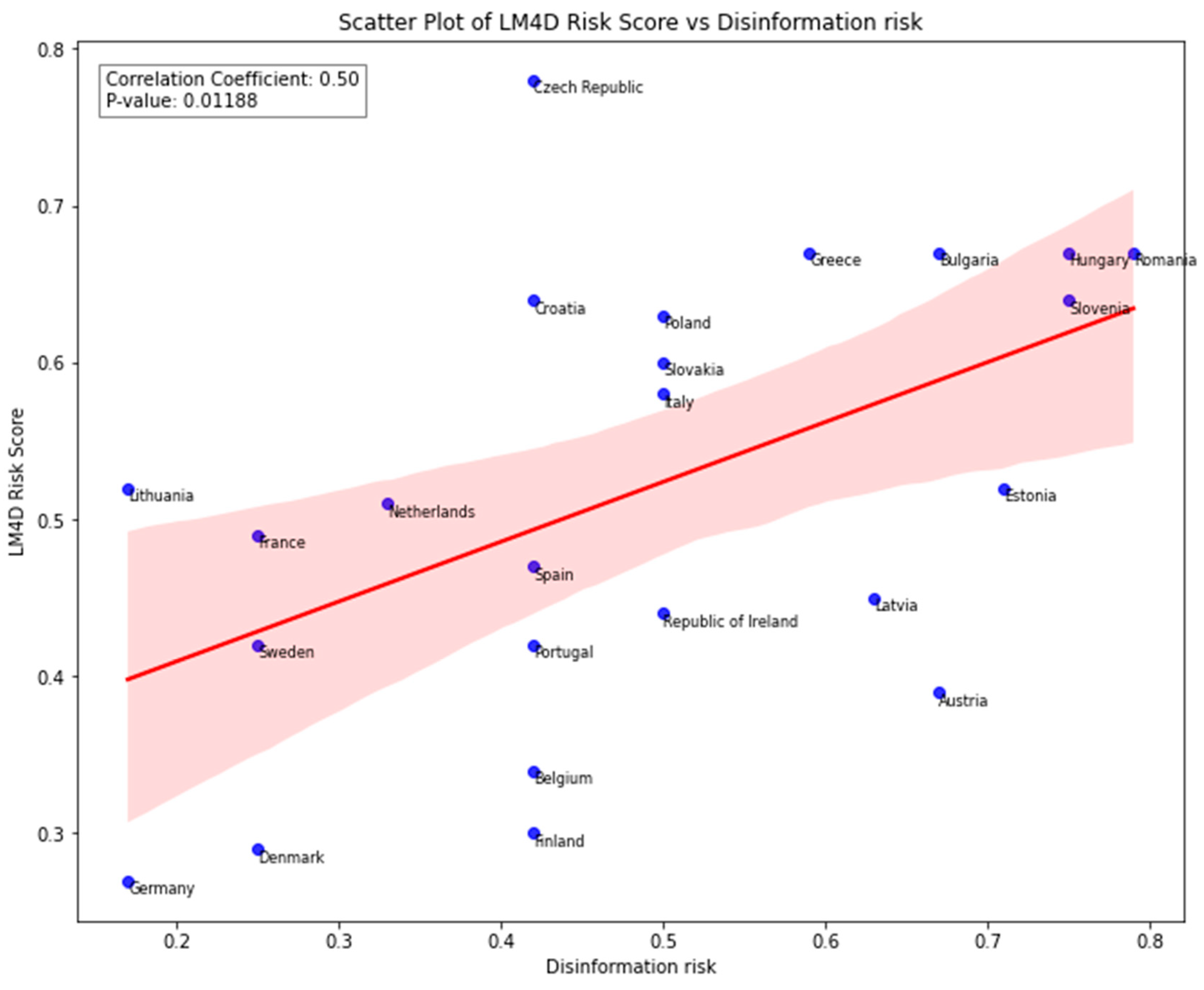

3.3. The Relationship between News Deserts and Disinformation

3.4. Hypotheses

- H1: There is a correlation between the quality of Public Service Media (PSM) and the risk of news desertification within a specific country.

- H2: There is a correlation between the prevalence of social media usage in a given country and the risk of news desertification.

- H3: The disinformation risk in a given country is correlated with the risk of news desertification.

4. Methodology and Research Design

5. Results and Discussion

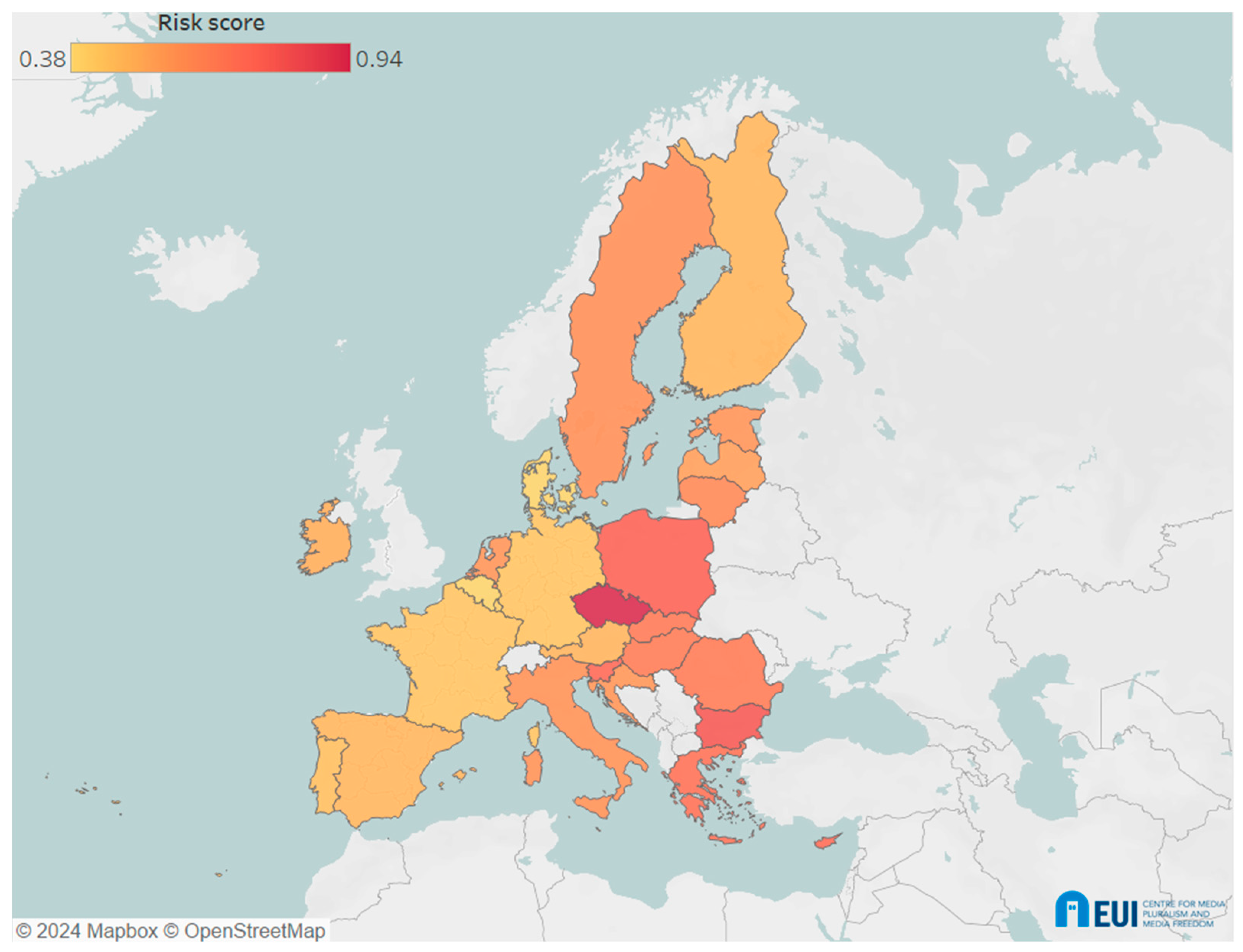

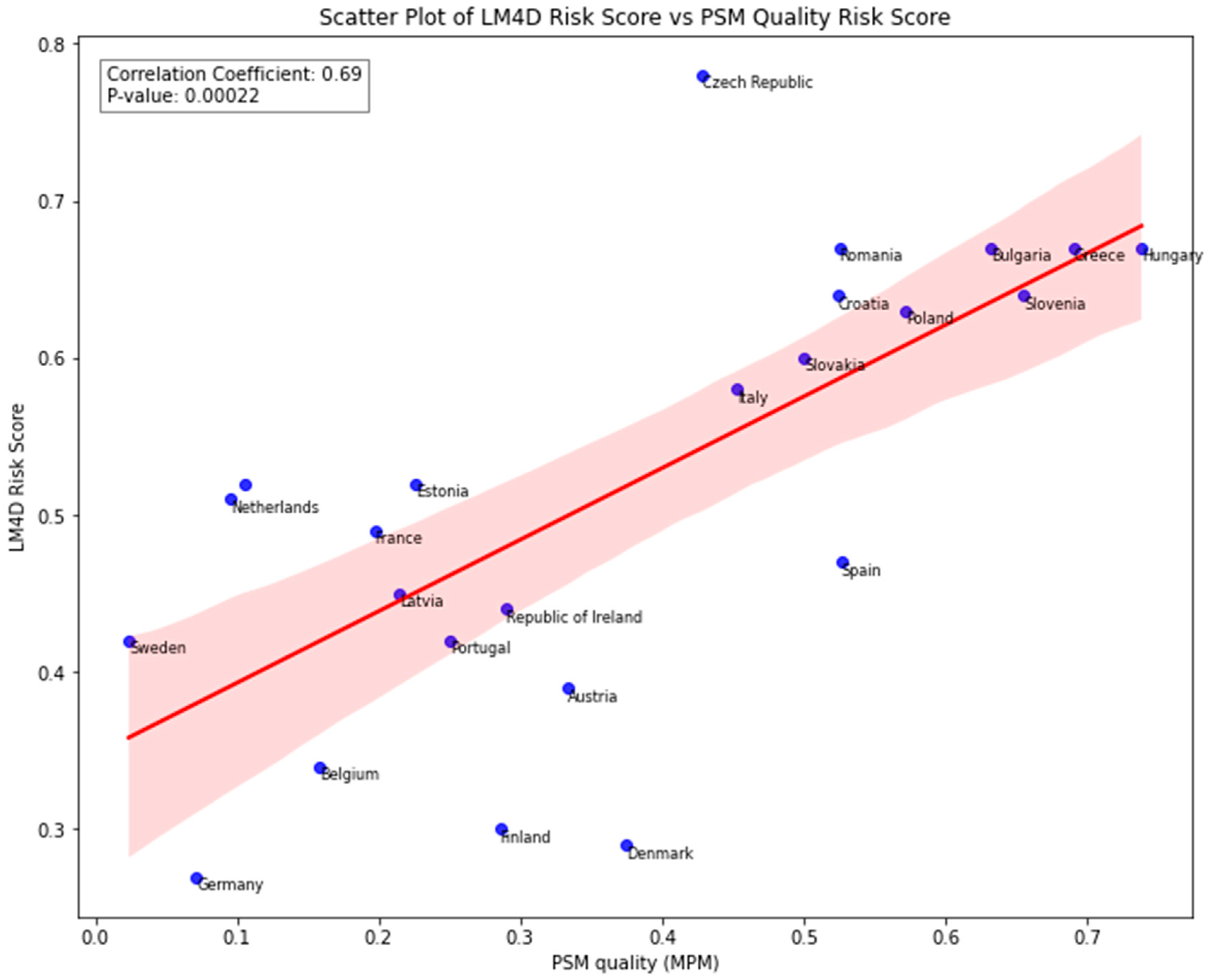

5.1. PSM Quality and News Desertification

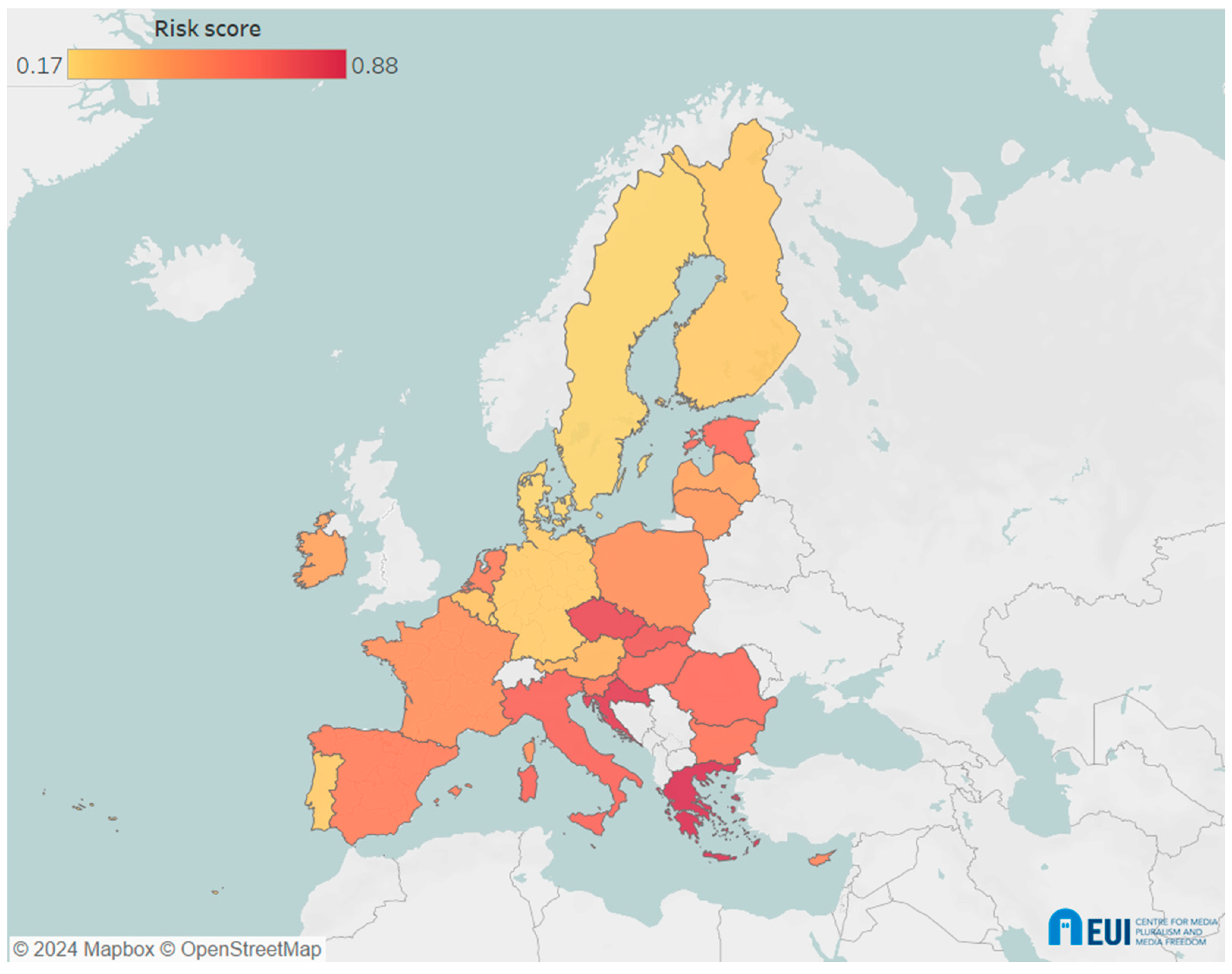

5.2. Social Media Usage and News Desertification

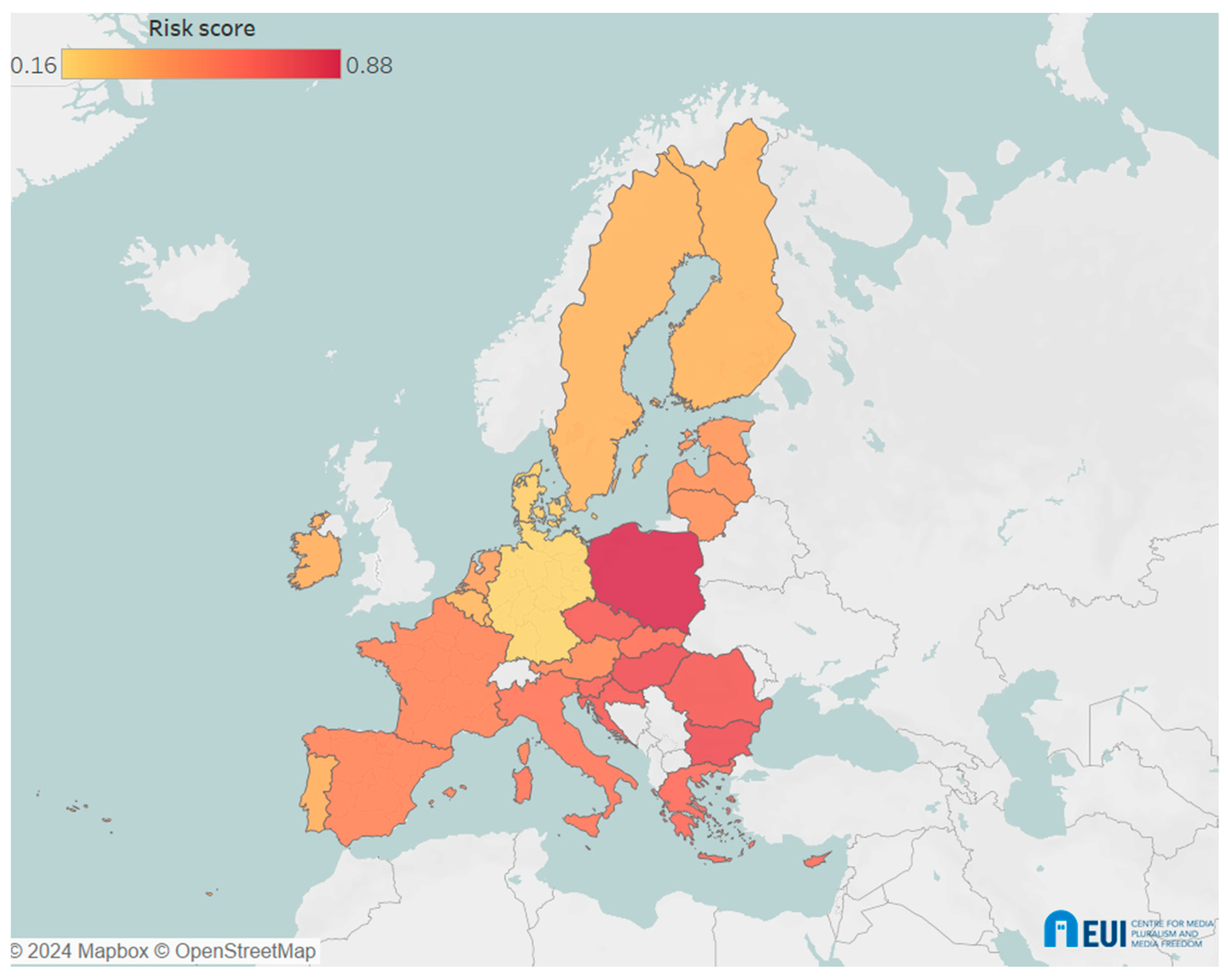

5.3. Disinformation and News Desertification

6. Limitations

7. Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Pearson’s correlation coefficient measures the direction and strength of linear relationship between two variables, which is represented by the r-value which ranges from −1 to 1. A number close to 1 or −1 indicates a strong positive or negative correlation and a number close to 0 indicates a weak correlation. The p-value indicates the statistical significance of the correlation coefficient. In more technical terms, the p-value is the probability of obtaining a test statistic at least as extreme as the one observed, if the null hypothesis (i.e., no correlation) is true. The commonly accepted threshold for statistical significance is 0.05. A linear model operates under the assumption that the relationship between variables is linear and data is normally distributed. It is important to acknowledge that the model’s sensitivity to outliers can significantly impact the results, so we should exercise caution when interpreting the results. |

| 2 | Media Pluralism Monitor 2023-CMPF (https://www.eui.eu/en/home, accessed on 27 May 2024). |

| 3 | DataReportal–Global Digital Insights. |

| 4 | These are sub-indicators of the 2023 Media Pluralism Monitor. For more information, please refer to this link: https://cmpf.eui.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/questionnaire-MPM-2023.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024). |

| 5 | CMPF-Variables-2023 (https://www.eui.eu/en/home, accessed on 27 May 2024). |

| 6 | https://cmpf.eui.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/questionnaire-final-05.6.23.pdf (accessed on accessed on 27 May 2024). |

| 7 | Transparency International. (2024). 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index. Transparency.org. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023/ (accessed on 27 May 2024). |

| 8 | Reporters without Borders. (2023). Index|RSF. Rsf.org. https://rsf.org/en/index (accessed on 27 May 2024). |

References

- Abernathy, Penelope Muse. 2020. News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive? Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, Annie. 2023. An Illustrated Guide to ‘Pink Slime’ Journalism. Poynter. Available online: https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/media-literacy/2023/pink-slime-journalism-local-news-deserts/ (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Andı, Simge. 2021. How and Why Do Consumers access News on Social Media. Reuters Institute Digital News Report, June 23. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, Steven, Steve Barnett, Martin Moore, and Judith Townend. 2022. Local News Deserts in the UK What Effect Is the Decline in Provision of Local News and Information Having on Communities? Available online: https://publicbenefitnews.files.wordpress.com/2022/06/local-news-deserts-in-the-uk.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Barnidge, Matthew, and Michael Xenos. 2021. Social media news deserts: Digital inequalities and incidental news exposure on social media platforms. New Media & Society 26: 368–88. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2021. Local Democracy Reporting Service. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/lnp/ldrs (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Blagojev, Tijana, Danielle Da Costa Leite Borges, Elda Brogi, Jan Erik Kermer, Matteo Trevisan, and Sofia Verza. 2023. News Deserts in Europe: Assessing Risks for Local and Community Media in the 27 EU Member States. Available online: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75762 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Bleyer-Simon, Konrad, Elda Brogi, Roberta Carlini, Danielle Borges, Iva Nenadic, Marie Palmer, Parcu Pier Luigi, Trevisan Matteo, Sofia Verza, and Mária Žuffova. 2023. Monitoring Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the Year 2022. Fiesole: Europeen University Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokša, Michal. 2022. Russian Information Warfare in Central and Eastern Europe: Strategies, Impact, Countermeasures. Washington, DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Cañedo, Azahara, Belén Galletero Campos, David Centellas, and Ana María López Cepeda. 2023. New Strategies for Old Dilemmas: Unraveling how Spanish Regional Public Service Media Face the Platformization Process. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodistico 29: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Innovation and Sustainablity in Local Media. 2018. What Is Exactly Is a “News Desert”? Available online: https://www.cislm.org/what-exactly-is-a-news-desert/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF). 2023. What are “News Deserts” in Europe? Available online: https://cmpf.eui.eu/what-are-news-deserts-in-europe/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF). 2024. Local Media for Democracy—Research Results. Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom. Available online: https://cmpf.eui.eu/local-media-for-democracy-research-results/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Collier, Jessica Renee, and Emily Graham. 2022. Even in “News Deserts” People Still Get News. Center for Media Engagement. Available online: https://mediaengagement.org/research/people-still-get-news-in-news-deserts (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Council of Europe. 2009. Recommendation 1878 2009 The Funding of Public Service Broadcasting. Assembly.coe.int; Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly. Available online: http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=17763&lang=en (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Council of Europe. 2022. Public Service Media. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/leaflet-public-service-media-en/1680735c27 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Council of Europe. 2023. Local and Regional Media: Watchdogs of Democracy, Guardians of Community Cohesion. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/local-and-regional-media-watchdogs-of-democracy-guardians-of-community/1680accd26 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Cushion, Stephen. 2018. Journalism under (ideological) threat: Safeguarding and enhancing public service media into the 21st century. Journalism 20: 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desilon, Daniels. 2021. Supporting Local News in North America. Public Media Alliance. Available online: https://www.publicmediaalliance.org/supporting-local-news-in-north-america/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- De Swert, Knut, Andreas Schuck, Mark Boukes, Nikki Dekker, and Bieke Helwegen. 2023. Monitoring Media Pluralism in the Digital Era: Application of the Media Pluralism Monitor in the European Union, Albania, Montenegro, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey in the Year 2022. Country Report: The Netherlands. Fiesole: Europeen University Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, Tomás, Claes de Vreese, Natali Helberger, Valeria Resendez, and Theresa Seipp. 2023. Popularity-driven Metrics: Audience Analytics and shifting opinion power to digital platforms. Journalism Studies 24: 403–21. [Google Scholar]

- European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 2012. Empowering Society a Declaration on the Core Values of Public Service Media. Available online: https://www.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/ebu/files/Publications/EBU-Empowering-Society_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- European Broadcasting Union (EBU). 2018. Trust in Traditional Media Increases across Europe. Available online: https://www.ebu.ch/news/2018/02/trust-in-traditional-media-increases-across-europe (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, and Content and Technology. 2023. Digital Services Act—Application of the Risk Management Framework to Russian Disinformation Campaigns. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/764631 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, Pier Luigi Parcu, Elda Brogi, Sofia Verza, Leite Da Costa, Danielle Borges, Roberta Carlini, Matteo Trevisan, Damian Tambini, Eleonora Maria Mazzoli, and et al. 2022. Study on Media Plurality and Diversity Online: Final Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/529019 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Fernandes, José Carlos, Myrian Regina Del Vecchio-Lima, André de Freitas Nunes, and Tatiana de Souza Sabatke. 2022. Jornalismo para investigar a desinformação em instância local. Interin 27: 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyas, Agnes. 2023. Local and Community Media in Europe: Comparative Analysis of the Media Pluralism Monitor Data between 2020 and 2023. Available online: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/75950 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Gulyas, Agnes, and David Baines. 2020. The Routledge Companion to Local Media and Journalism. Routledge eBooks. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyas, Agnes, and Kristy Hess. 2023. The Three “Cs” of Digital Local Journalism: Community, Commitment and Continuity. Digital Journalism 12: 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyas, Agnes, Sarah O’Hara, and Jon Eilenberg. 2019. Experiencing local news online: Audience practices and perceptions. Journalism Studies 20: 1846–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, Kirsty, and Lisa Waller. 2017. Local Journalism in a Digital World. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Minna, Stephen Cushion, Marius Dragomir, Sergio Gutiérrez Manjón, and Mervi Pantti. 2021. A Framework for Assessing the Role of Public Service Media Organizations in Countering Disinformation. Digital Journalism 10: 843–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husock, Howard. 2023. Could News Bloom in News Deserts? Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute. Available online: https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Could-News-Bloom-in-News-Deserts-Updated.pdf?x91208 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Hutchinson, Jonathon. 2017. Public Service Media. In Cultural Intermediaries: Audience Participation in Media Organisations. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, Will, Gerry Stoker, Hannah Bunting, Viktor Orri Valgarðsson, Jennifer Gaskell, Daniel Devine, Lawrence McKay, and Melinda C. Mills. 2021. Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 9: 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerónimo, Pedro. 2024. Local Journalism, Global Challenges: News Deserts, Infodemic and the Vastness in between. Covilhã: LabCom Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jerónimo, Pedro, Giovanni Ramos, and Luísa Torre. 2022. News Deserts Europe 2022: Portugal Report. Available online: https://labcomca.ubi.pt/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/news_deserts_europe_2022_.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Klatt, Nikolina, and Vanessa A. Boese-Schlosser. 2023. Authoritarianism and Disinformation: The Dangerous Link. Available online: https://theloop.ecpr.eu/disinformation-in-autocratic-governance (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Kroková, Kristína. 2022. Kríza Lokálnej Žurnalistiky–Národná Štúdia Slovensko. Bratislava: Transparency International Slovensko. Available online: https://transparency.sk/sk/mapa-printovych-spravodajskych-pusti/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Lakshmanan, A. Indira. 2018. Finally Some Good News: Trust in News is Up, Especially for Local Media. Available online: https://www.poynter.org/ethics-trust/2018/finally-some-good-news-trust-in-news-is-up-especially-for-local-media/ (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Mota, Dora. 2023. The Erosion of Proximity: Issues and Challenges for Local Journalism in Contemporary Society. Comunicação e Sociedade 44: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Hannah. 2024. “Pink Slime” Local News Outlets Erupt All over US as Election Nears. Available online: https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2024/04/pink-slime-local-news-outlets-erupt-all-over-us-during-election-year/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Negreira-Rey, María-Cruz, Jorge Vázquez-Herrero, and Xosé López-García. 2023. No people, no news: News deserts and areas at risk in Spain. Media and Communication 11: 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Kirsten Eddy, Craig Robertson, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2023. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, vol. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. 2015. Local Journalism the Decline of Newspapers and the Rise of Digital Media. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2017-12/Local%20Journalism%20-%20the%20decline%20of%20newspapers%20and%20the%20rise%20of%20digital%20media.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis, Robert Gorwa, and Madeleine De Cock Buning. 2019. What Can Be Done? Digital Media Policy Options for Strengthening European Democracy. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/What_Can_Be_Done_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Ognyanova, Katherine, David Lazer, Ronald Robertson, and Christo Wilson. 2020. Misinformation in action: Fake news exposure is linked to lower trust in media, higher trust in government when your side is in power. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSCE (HCNM). 2007. Recommendation CM/Rec20073 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Remit of Public Service Media in the Information Society. OSCE High Commissioner for National Minorities. Available online: https://milobs.pt/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Recommendation-CM-Rec20073-of-the-Committee-of-Ministers-to-member-states-on-the-remit-of-public-service-media-in-the-information-society.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- OSCE (HCNM). 2019. The Tallinn Guidelines on National Minorities and the Media in the Digital Age & Explanatory Note. Available online: https://www.osce.org/files/OSCE-Tallinn-guidelines-online%203.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Park, Jacqui. 2021. Local Media Survival Guide 2022: How Journalism Is Innovating to Find Sustainable Ways to Serve Local Communities around the World and Fight against Misinformation. Vienna: International Press Institute (IPI). [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jacqui. 2022. Local Media Survival Guide 2022. Available online: https://kq.freepressunlimited.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/local-media-survival-guide-2022.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Project Oasis. 2023. A Research Project on the Trends, Impact and Sustainability of Independent Digital Native Media in More than 40 Countries in Europe. Available online: https://projectoasiseurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Project-Oasis-PDF-April-17-2023.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Radcliffe, Damian. 2018. How Local Journalism Can Upend the ‘Fake News’ Narrative. Available online: https://theconversation.com/how-local-journalism-can-upend-the-fake-news-narrative-104630 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Reviglio, Urbano. 2023. The Ambivalent and Ambiguous Role of Social Media in News Desertification. Available online: https://cmpf.eui.eu/the-ambivalent-and-ambiguous-role-of-social-media-in-news-desertification/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Saiz-Echezarreta, Vanesa, Belén Galletero-Campos, and Daniela Arias Molinares. 2023. From news deserts to news resilience: Analysis of media in depopulated areas. Journalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, Holli, Eliska Pirkova, Matthias C. Kettemann, Marlena Wisniak, Martin Scheinin, Emmi Bevensee, Katie Pentney, Lorna Woods, Lucien Heitz, Bojana Kostic, and et al. 2022. Spotlight on Artificial Intelligence and Freedom of Expression: A Policy Manual. Vienna: Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Skender, Melisa. 2023. Medijske Pustinje. Available online: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/melisa7395/viz/medijske_pustinje/Dashboard1 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Toff, Benjamin, and Nick Mathews. 2021. Is social media killing local news? An examination of engagement and ownership patterns in US Community news on Facebook. Digital Journalism, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Broek, Rijk, and Yael De Haan. 2020. Lokale Journalistiek in Nederland. Available online: https://d1z7tyvg4tle90.cloudfront.net/visualisatie-lokale-media-2020/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Vannier, Denis. 2020. Combien de Médias Locaux en France? Available online: https://www.festival-infolocale.fr/medias-locaux-aidez-nous-a-vous-compter/ (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Verza, Sofia, Tijana Blagojev, Daniele Da Costa Leite Borges, Jan Erik Kermer, Matteo Trevisan, and Urbano Reviglio Della Venaria. 2024. Uncovering News Deserts in Europe: Risks and Opportunities for Local and Community Media in the EU: Final Report. Available online: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/76652 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Weber, Matthew, Peter Andringa, and Philip Napoli. 2019. Local News on Facebook: Assessing the Critical Information Needs Served through Facebook’s Today-in Feature. News Measures Research Project. Available online: https://hsjmc.umn.edu/sites/hsjmc.umn.edu/files/2019-09/Facebook%20Critical%20Information%20Needs%20Report.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Yadamsuren, Borchuluun, and Sanda Erdelez. 2016. Incidental exposure to online news. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services 8: i-73. [Google Scholar]

- Zickgraf, Ryan, Penelope Muse Abernathy, and Meredith Wilson. 2023. News Deserts—How the Loss of Local Reporting Fuels Disinformation. Evergreen Podcasts. Available online: https://evergreenpodcasts.com/disinformation/news-deserts (accessed on 15 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kermer, J.; Reviglio, U.; Blagojev, T. “News Desertification” in Europe: Highlighting Correlations for Future Research. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 718-738. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020047

Kermer J, Reviglio U, Blagojev T. “News Desertification” in Europe: Highlighting Correlations for Future Research. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(2):718-738. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020047

Chicago/Turabian StyleKermer, Jan, Urbano Reviglio, and Tijana Blagojev. 2024. "“News Desertification” in Europe: Highlighting Correlations for Future Research" Journalism and Media 5, no. 2: 718-738. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020047

APA StyleKermer, J., Reviglio, U., & Blagojev, T. (2024). “News Desertification” in Europe: Highlighting Correlations for Future Research. Journalism and Media, 5(2), 718-738. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020047