Abstract

In the context of increasing online health misinformation, several new approaches have been deployed to reduce the spread and increase the quality of information consumed. This systematic review examines how source credibility labels and other nudging interventions impact online health information choices. PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for studies that present empirical evidence on the impact of interventions designed to affect online health-information-seeking behavior. Results are mixed: some interventions, such as content labels identifying misinformation or icon arrays displaying information, proved capable of impacting behavior in a particular context. In contrast, other reviewed strategies around signaling the source’s credibility have failed to produce significant effects in the tested circumstances. The field of literature is not large enough to draw meaningful conclusions, suggesting that future research should explore how differences in design, method, application, and sources may affect the impact of these interventions and how they can be leveraged to combat the spread of online health misinformation.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Spread of Online Health Misinformation

In the European Union (EU), the percentage of households with internet access is 93.09 (Eurostat 2023), and 72% of EU internet users have reported using it to consume news (Eurostat 2022). It has never been easier to access information online.

The internet has become a popular resource for people from all social groups, regardless of gender or age, to learn about health. However, the informal and unsupervised way people interact with health information online is fertile ground for misinformation (Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez 2021; Swire-Thompson and Lazer 2020).

Online health misinformation refers to false or misleading information about health issues that is shared online.

This general definition would consider, on the one hand, information that is false but not created to cause harm (i.e., misinformation) and, on the other, information that is false or based on reality but deliberately created to harm a particular person, social group, institution, or country (i.e., disinformation and malinformation) (Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez 2021).

Online health misinformation has been around for many years, but it gained prominence, both socially and in scientific literature, in the wake of the COVID-19 global pandemic (Smith et al. 2023). During this period, the global epidemic generated an overwhelming amount of interest and, consequently, information, with varying degrees of accuracy, that was spread by all available channels, all the time, with various social, political, and health consequences (Balakrishnan et al. 2022). In this context, an infodemic—a word that aptly describes how information spreads like a virus (Rothkopf 2003)—was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO), in the wake of which stakeholders such as Governments, digital online platforms, NGOs, startups, and other health organizations expanded their efforts to come up with innovative and effective approaches to curb the spread of online health misinformation (WHO Regional Office for Europe 2022).

Countering online health misinformation became an urgent imperative, but doing so usually involves some form of speech regulation, censure, and truth-monitoring (Marecos et al. 2023), an arduous equilibrium between freedom of speech and protection from false speech (Marecos and de Abreu Duarte 2022). Nevertheless, social media platforms adopted and enforced stricter content rules, from labeling to nudging, blocking monetization on specific topics and outright erasing and banning content and accounts (WHO Regional Office for Europe 2022).

In a context of overabundance of information, choice matters; therefore, solutions designed to induce choice of sources and content have been developing at an increased pace.

As an emerging approach, the labeling of online information represented an exciting case of attempting to curb misinformation not by suppressing speech but by adding speech in the form of an informational label that suggests to an audience that certain content is more credible than others (Morrow et al. 2022).

Credibility, and particularly source credibility, has been researched in intimate connection to two concepts that are key to the decision to “believe” in something: “trustworthiness” (perceived honesty, fairness and integrity) and “expertise” (perceived knowledge) (Riley et al. 1954); and, more recently, in connection with the “attractiveness” (perceived likability and familiarity) of the source (Seiler and Kucza 2017). A more credible source is more likely to persuade the audience to adopt a behavior (Pornpitakpan 2004), so there is an apparent gain in diverting audiences to specific sources (deemed accurate) based on their “credibility”.

Labeling information certainly sidesteps the “freedom of speech” obstacle of many anti-misinformation initiatives (whilst nonetheless creating others, as briefly explained below). Still, questions remain about whether or not the type of interventions usually associated with “labeling information” actually impacts the audience’s behaviors and perceptions, particularly in an online environment and on health topics.

Furthermore, “labeling” is one of many ways in which credibility can be nudged, and the method, as much as the approach, likely influences how impactful an intervention can be.

This systematic review article addresses those questions by examining published literature on source credibility labels (and other similar nudging interventions) to discover if there is sufficient evidence of a link between those interventions and the ability to influence information choices.

1.2. Nudging

In behavioral science, a “nudge” can be described as an intervention (ideally informed by evidence-based behavioral insights) aiming to present a choice to an individual in a certain manner that will lead to a predictable change in behavior. They are meant to keep decision-making autonomy by neither restricting options nor substantially altering incentives (Adkisson 2008).

This can be achieved, for example, by adding content and/or design elements (such as labels, ticks, warnings, alerts) or modifying it (rewriting, simplifying, rearranging order) (United Nations Behavioural Science Report 2021), with such new or modified elements guiding behavior even despite of awareness.

For example, the blue tick that identified “verified users” on the social media formerly known as Twitter, albeit expressly not an “endorsement” of what they published by the platform, was given by the platform to “public interest accounts” to establish trust in the “identity” of that user, and it ended up being considered a symbol of status (Barsaiyan and Sijoria 2021).

Another example is the order in which Google and other similar search engines rank search results differently, depending on what type of choice they want to nudge. In Google’s case, during the COVID-19 infodemic, the decision was made to prioritize government-related sources by showing them more frequently than any other providers (Makhortykh et al. 2020).

Nudging credibility in online health information is, therefore, intervening in what an audience sees when accessing information to lead them towards certain behaviors and away from others. However, there is, on the one hand, a lack of clarity as to the effectiveness of nudging techniques in an online health information context, and on the other, there are several ethical and value-based concerns that should be addressed (Ledderer et al. 2020).

1.3. Labeling Source Credibility in a Health Context

There are several approaches when it comes to labeling the credibility of online health information. These approaches could be categorized in multiple ways, for example, based on who conducts the credibility assessment (doctors, researchers, journalists, AI, social media users, online platforms, NGOs), or they could be categorized by design (visual label, descriptive label) or by the type of message they want to convey (credibility or lack thereof, truthfulness, accuracy, etc.). Labels can communicate something about the source (reputation, trustworthiness, etc.) or something about the content (truthful, disputed, etc.).

Some source credibility labeling approaches communicate only when a source is considered highly credible or quality. These include the now discontinued Health On the Net (HON) certification (Boyer et al. 1998), known as HONcode, and the Patient Information Forum’s Trusted Information Creator Kitemark (PIF TICK).

Both certifications involve an assessment by medical experts or healthcare professionals. Upon successful evaluation, those sources can display the respective labels on their platforms, signaling their credibility as assessed by these external reviewers. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram have also adopted this approach by selectively promoting specific sources of OHI as credible, particularly during the pandemic (Combatting Misinformation on Instagram|Instagram 2019).

We can also identify approaches that communicate not when a source is credible but when a source has low credibility, serving as a warning and deterrent to audiences. One example was a browser extension developed by Logically.ai, which utilized artificial intelligence to identify and warn users about potentially dangerous websites due to their lack of credibility. When visiting a website with poor credibility, a label would appear across the screen, informing the user of the potentially dangerous nature of the content (Brown 2020). Another example is Twitter’s use of labels to caution users about the credibility of specific content. This approach aims to influence audiences’ choices before they engage with the content by warning them of the low credibility of a source or information (Our Synthetic and Manipulated Media Policy|X Help 2023).

Some approaches may communicate source credibility by analyzing high- and low-credibility sources, usually displaying some rating. Newsguard, a media startup focused on anti-misinformation tools, employs journalists to review websites based on credibility and transparency criteria, resulting in a rating from 0 to 100. Websites with a score below 50 were marked with a red label, while those above 50 were marked with a green label. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Newsguard launched Healthguard, a health-focused solution applying the same methodology to OHI sources. Newsguard has, in the meantime, moved on from the color scheme and now presents a rating from 0 to 100 (Website Rating Process and Criteria—NewsGuard 2023).

Media Bias/Fact Check, another independent organization, employs a mixed-label approach, assessing media bias and labeling websites accordingly (About-Media Bias/Fact Check 2023). These mixed labels offer a more nuanced understanding of source credibility by giving users a spectrum of credibility ratings.

The goal of this section is not to provide a comprehensive overview of the multiple ways in which it is possible to nudge audiences with credibility labels but rather to illustrate such variety to contextualize the decisions made by the authors when conducting this review.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review followed the guidelines of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al. 2009).

The question that guided our research was: “Do source credibility labels impact the choice of online health information?” Our objectives were to identify the current state of the literature on the use of source credibility labels for online health information, to evaluate the effectiveness of these labels in reducing the consumption and belief of online health misinformation, and to provide recommendations for future research and policy.

2.1. Search Strategy

We used the following electronic databases in the search: PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search was conducted in November 2023. We have initially identified three key concepts:

- By referring to the “treatment”: the “source credibility labels”;

- By referring to the “disease”: “misinformation”;

- By limiting it to the relevant context: “online information”.

As there is no established language to refer to this particular type of intervention, we have generated a list of related terms that we have found to be used to refer to each of these three concepts. More information about this process can be found in Appendix A.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if (i) they directly or indirectly investigate the impact of source credibility labels (or similar nudging interventions) on the choice of online health information to consume; (ii) they present empirical data to assess impact; (iii) they were made available in the English language and in full-text.

The Inclusion of Similar Nudging Interventions

As part of our iterative process for this systematic literature review, we have concluded at a certain point that the field of literature around source credibility labels and how they impact choice in an online health information context was not sufficiently large to yield relevant results. As such, and since the search string was designed to capture the reality of labeling source credibility in multiple formats, we have also included studies that analyzed similar nudging interventions, whose results and approaches may help illuminate future avenues of research for those interested in source credibility labeling.

Examining the effectiveness of these interventions provides insights into digital nudging strategies’ mechanisms, which could be translatable to other similar interventions such as source credibility labels.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

We have excluded studies that (i) were not focused on specific nudging interventions in the context of online health (such as, for example, studies that measure the quality of the information on a certain disease in a certain platform); (ii) did not present empirical findings; (iii) were not available in English and in full text.

2.4. Assessment of Risk of Bias

The risk of bias was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tool known as the “Checklist For Quasi-Experimental Studies” (Aromataris et al. 2015). This assessment involved responding to 9 specific questions with either “yes”, “no”, or “not applicable”. Studies were then categorized based on their risk of bias as low (>70%), moderate (40–70%), or high (<40%). A detailed summary of this evaluation is available in Appendix B.

3. Results

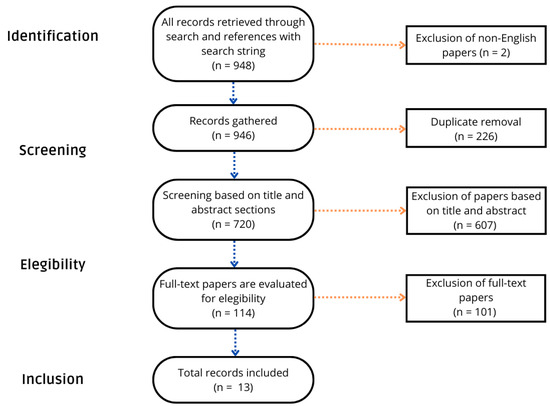

Our search resulted in 948 research articles. Non-English papers and duplicate records were identified and removed during this phase, which left 720 studies. A first screening based on title and abstract eliminated studies that clearly did not meet our inclusion criteria. The remaining 114 studies were reviewed in full to exclude papers that did not focus on specific online health nudging interventions and/or did not present empirical evidence of impact. In the end, 13 studies were included in the systematic review. The risk of bias analysis resulted in 11 studies being considered as low risk. In the other two cases, none of the questions were applicable. This process is illustrated in Figure 1, below.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

The 13 studies identified as eligible cover a range of interventions in an online context on health-related content and are summarized in Table 1, below. Given the relative novelty of online health misinformation as a research topic, the earliest study dates from 2007, and more than half of the papers reviewed were published from 2020 onwards.

Table 1.

Summary of interventions, results, and environments.

This aligns with our earliest considerations around the surfacing of online health misinformation as a highly relevant topic in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Each paper focuses on different types of interventions applied to different environments to measure different things, which hurts comparability. In common, they study interventions that can be globally included in the “fight false speech with more speech”, i.e., the type of interventions that add new informational layers to the content to nudge behaviors.

Five papers focus on two different forms of labeling: source credibility labels (Barker et al. 2010; Bea-Muñoz et al. 2016), such as the HealthOnNet Code seal; and content labels, either warning about the existence of a fact-checking article about the content (Zhang et al. 2021) or warning about potential misinformation in the content (Zhang et al. 2022; Folkvord et al. 2022).

The papers that cover source credibility labels are not specifically designed to test the impact of these interventions but rather comment on it as a byproduct of their experiments. In both cases, the presence of source credibility labels led neither to an increase in accuracy (Barker et al. 2010) nor to an increase in the readability or quality of the information (Bea-Muñoz et al. 2016).

Experiments on content labels, on the other hand, revealed mixed results: one found that labels placed directly under posts containing misinformation about vaccines can positively change people’s opinions towards vaccines (Zhang et al. 2021); another found that strongly worded content labels may be counter-effective due to disconfirmation bias, and that softly worded labels are more effective to convey content corrections (Zhang et al. 2022); and the other found limited effects in the improvement of credibility and validity beliefs (Folkvord et al. 2022).

Bates et al. (2007), the earliest paper in our review, investigated whether varying levels of literacy proficiency (eighth grade, ninth grade, and first-year college) affected perceived trustworthiness, truthfulness, readability, and completeness of online health content. It found that enhancing the reading level of online information did not significantly influence consumers’ evaluations of these criteria.

Other papers focused on the influence of social endorsement cues (Borah and Xiao 2018) and visual displays on credibility perceptions (Giese et al. 2021). Borah and Xiao demonstrated that the number of “likes” on Facebook posts positively affected credibility perceptions of health information. Their findings highlight the need for strategies to mitigate the impact of social endorsement on misinformation spread. On the other hand, Giese et al. (2021) investigated the impact of using icon arrays to communicate scientific flu vaccine effectiveness information. They found that graphic displays can play a crucial role in enhancing the comprehension and credibility of health information. This suggests that presenting complex health information in visually accessible formats can facilitate knowledge dissemination and enhance users’ engagement with online health content.

One paper focused on providing participants with four context articles on specific health topics, two for and two against, from sources with differing credibility degrees (Westerwick et al. 2017). The paper measured how such exposure impacted the participants’ stance on health topics related to those articles and found that participants who accessed the context articles tended to align their behavior accordingly (either adopting promoted behaviors or not adopting discouraged behaviors). It was also found that this influence is stronger when messages come from more credible sources.

In a different intervention, a paper (Jongenelis et al. 2018) aimed at finding out if showing people information about the link between alcohol and cancer from various sources and in different ways during an online simulation leads to greater improvements in their attitudes and intentions than just showing them information from one source. People who encountered the messages through several different sources found them more credible, persuasive, and personally significant than those who only saw them through one source. Significant enhancements were observed in various measures before and after exposure, except for participants who were exposed to the message through a single source and reported no change in their belief regarding reducing their consumption. These findings suggest that employing multiple sources to deliver messages may produce cumulative effects.

Adams et al. (2020) reached a different conclusion when examining the impact of incorporating high-quality quantitative evidence regarding treatment outcomes into relevant Wikipedia pages on information-seeking behavior. Wikipedia pages in the intervention group were modified to include tables presenting the best evidence of treatment effects and hyperlinks to the source. In contrast, pages in the control group remained unchanged. The primary outcome measures included routinely collected data on access to full-text articles and page views after 12 months. The study found no significant evidence of an effect on the primary outcomes of full-text access or page views, suggesting that including authoritative quantitative supporting evidence does not meaningfully impact information-seeking behavior.

In Boutron et al. (2019), in a series of Internet-based randomized trials, the effect of “spin” (i.e., biased reporting) on interpreting news stories on medical studies was investigated across three different trial stages. The primary outcome measure was participants’ interpretation of the news, assessed through a specific question on the perceived likelihood of treatment benefit on a scale from 0 (very unlikely) to 10 (very likely). Results showed that participants were more inclined to believe in the beneficial effects of the treatment when the news story was presented with spin; for pre-clinical studies, the mean score for interpretation was higher when the news contained spin compared to control (7.5 vs. 5.8). Significant differences were also observed for phase I/II non-randomized trials (7.6 vs. 5.8) and phase III/IV RCTs (7.2 vs. 4.9), indicating a consistent pattern of biased reporting leading to higher perceptions of treatment efficacy among participants. These findings stress the importance of considering the potential impact of spin in shaping public perceptions and decision-making regarding medical treatments.

Vu and Chen (2023) focused on three different interventions. In the first, they studied the impact of differing author credentials on perceptions of article credibility, intentions to follow behavioral recommendations, and intention to share. The author’s credentials were manipulated to suggest high or low expertise. No statistically significant difference between the high and low author credentials conditions was found across the dependent variables, suggesting that manipulating author credentials did not influence participants’ perceptions of article credibility, their intentions to follow the article’s recommendations, or their intentions to share the article.

The second focused on the effect of journalistic writing style. The design involved two variations of the same article: one with a high-quality journalistic writing style characterized by neutral language and an inverted pyramid structure, and the other using a low-quality journalistic style marked by casual language and less structured presentation. Again, no statistically significant differences were found between the two writing style conditions, suggesting that the journalistic quality of the writing style did not significantly impact participants’ engagement with the article.

Finally, the third intervention focused on the influence of using a verification check flagging. Each article was marked with either a verification passing cue (a green checkmark communicating that the article passed a third-party verification check) or a verification failing cue (a red X mark stating that the article had failed a third-party verification check). In this case, it was found that the verification checks significantly affected all three dependent variables. Participants in the verification-passing condition were more likely than those in the verification-failing condition to show an intention to follow behavioral recommendations, perceive the article as credible, and express an intention to share the article.

Overall, from the 15 interventions researched in the 13 papers that resulted from this literature review, 8 have concluded that the researched intervention presents some sort of positive effect in impacting information-seeking behavior, 7 seven recognize no significant effects, 4 are set in a social media environment (Facebook and Twitter), 7 were designed to reflect the experience of reading website articles, and 2 were online surveys.

Outside this review’s scope were several studies on the quality of information on specific topics and platforms, providing comparable results across specific diseases and environments. Such variety and replication of designs could not be found in our case, reflecting the lack of depth of the information available. Does social endorsement influence credibility perceptions across different social media platforms or just Facebook? Are verification checks effective on social media posts or just on online health articles? Are other graphic representations as effective as icon arrays in increasing the willingness to share information? These are but some of the questions that may guide future research and that we expand below.

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

We started this review with the expectation of finding a broader field of literature on source credibility labels in the context of online health information, particularly with publishing dates from the past 10 years, where usage of social media skyrocketed, conspiracy theories around vaccination and COVID-19 gained prominence, and digital platforms became more active in strategies against health misinformation.

However, even after expanding the scope of the search to include interventions other than source credibility labels, we found out that the field of literature focused on interventions geared to impact how audiences interact with online health information is still relatively small.

Specifically on source credibility labels, there are very few studies focused on the many iterations of these types of intervention, which can be explained up to some point by the relatively recent reemergence during COVID-19 but fails to reflect the reason behind the lack of studies on the impact of labels such as the HON Code seal (launched in 1995), the NHS Information Standard (2015), and Healthguard (2020), to name just a few.

Information labels are not novel, and some traditional labeling research provides essential support for understanding some of the challenges of online labeling (Yeh et al. 2019). However, as labeling information online has become a popular solution among gatekeepers (WHO Regional Office for Europe 2022), from digital platforms to fact-checkers, its impact in a digital environment, particularly with respect to nudging behavior and in the context of online health misinformation, remains underexplored.

In the broader online misinformation context, some important work has emerged in this field that can naturally also be of interest in a health context. Notably, a study by Aslett et al. (2022) has examined the efficacy of Newsguard source credibility labels as a deterrent to the propagation of false information in social media feeds and search results. Using a mix of participant questionnaires and digital activity tracking, the study sought to determine whether or not exposing participants to those labels on an ongoing basis could change how people consume the news. Despite taking a thorough approach, the study did not find any significant changes in the amount of low-quality news that participants consumed over the course of three weeks, nor did it notice any changes in the belief in misinformation and accuracy claims. This study suggests that exposure to source credibility labels, on an ongoing basis, may not be the solution that many had hoped would meaningfully change behavior. However, there is room to question how well such a conclusion translates to an online health information context. In fact, as the authors recognized, the fact that the current landscape for news consumption is highly polarized, the subtlety of credibility labels may not be sufficient to meaningfully change behaviors towards news; however, one can imagine that online health information, which can and should be rooted in scientific evidence, and is less affected by polarization (with notable exceptions around vaccination and certain conspiracy theories), may yield different results.

Another experiment, this time with “credibility badges”—which indicated the credibility score of each source—showed that the participants’ capacity to discriminate between accurate and false information was significantly improved by the presence of such badges, leading to a decrease in their acceptance of the latter and an increase in their belief in the former (Prike et al. 2024).

However, the ambiguity of the empiric evidence on the impact of these interventions—both in a health context and more broadly—suggests that further research is required to gain a deeper understanding of how impactful solutions like source credibility labels can be, and how can those effects be maximized.

4.2. Future Research

The avenues for future research are substantial, particularly with online health news. The landscape of digital health information is rapidly evolving, presenting both opportunities and challenges for effectively combating misinformation. We summarize the ones we have identified below:

- Examining different types of credibility labels: Future research should explore the impact of some of the source credibility labels currently in existence to understand their unique impacts on online health information consumption. It would also be useful to understand how impact changes from credibility labeling schemes such as PIF Tick (which communicates only positive credibility) to Healthguard (which communicates both positive and negative credibility) to warning labels such as those found in digital platforms (which communicate only negative credibility).

- Examining source perception: It would be useful to understand how incorporating a reference to the nature of the source (e.g., journalistic, governmental, health institutions, health experts, etc.) impacts decision-making in source selection, source confidence, and decision to share content from sources.

- Examining labeler perception: Similarly, it would be interesting to understand if audiences react differently to labels depending on who assessed the source and issued the label (e.g., doctors, journalists, health institutions, government, artificial intelligence, etc.).

- Comparative studies across different health topics: Research could compare the effectiveness of interventions across various health topics, including those that are highly polarized like vaccination and COVID-19, to those that might be less controversial in order to understand how polarization contaminates perception and impact.

- Impact on behavior change: Future research should aim to measure not just belief changes but also whether these interventions lead to actual behavior change, like intent to share.

- Cross-demographic studies: Considering the cultural context in the acceptance of health information, studies should examine how these interventions work across different cultures and regions, different ages and education levels, and different socioeconomic levels.

- Cross-environment studies: Since labeling can be applied in multiple contexts, it would be interesting to develop research comparing how its impact may vary depending on the environment (e.g., how the same approach compares when applied to X, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Google search results; and how different environments may benefit from certain approaches versus others).

- Label design studies: Different labeling designs have been applied over time, and creativity may unlock different manners of conveying information on source credibility when applied to online health information. Designs such as ribbons, seals, stamps, marks, ticks, non-textual and textual, color-coded or not, numerical, etc., may yield different results that should be assessed.

- Integration with social media platforms: Researching the collaboration between health organizations and social media platforms could yield insights into how to effectively implement these labels in the places where people most often encounter health misinformation.

- Effectiveness of different intervention combinations: Exploring how different combinations of nudging interventions work together could provide a more nuanced understanding of how to combat online health misinformation.

- Public perception and trust in labels: Future research could also focus on how the public perceives these credibility labels and interventions and how trust in these labels can be built over time in order to increase its impact.

- Role of fact-checking organizations: Understanding how interventions can be supported or enhanced by fact-checking organizations and the impact of their endorsement on public trust and information assessment.

- Technology and algorithm influence: Examining how technology and algorithms can be optimized to support the visibility and effectiveness of these labels, including the role of artificial intelligence in flagging misinformation.

Despite the ample research opportunities, it should be noted that research in this field also needs to consider plenty of challenges, namely:

- The fast-paced nature of online platforms and online behaviors, which can quickly render interventions obsolete;

- The difficulty in designing interventions that are effective across diverse demographic groups without inadvertently amplifying misinformation;

- The challenge of measuring the real-world impact of online interventions on health outcomes, which requires complex, interdisciplinary approaches;

- The legitimacy issue of the “labeler” and how to create frameworks that ensure that credibility assessments are underpinned in objective and determinable criteria;

- The advent of artificial intelligence, how it will shift the paradigm around the creation of info- and misinformation, and how it can be leveraged to both prevent and spread online health misinformation;

- The potential for resistance from users who perceive credibility labels and interventions as forms of censorship or bias, which possibly reduced their effectiveness;

- Finally, the technical and ethical considerations in implementing these interventions including scalability concerns and the need for transparency and accountability in how information is labeled and moderated.

4.3. Limitations

We must acknowledge certain limitations in our review despite our best efforts.

This field lacks common terminologies. Even though we tried to include as many alternative terms in our search strings as possible, it is possible that we have failed to find and include relevant studies. Also, we focused only on English-language literature, which means that we may have overlooked potentially valuable contributions made in other languages, which may impact our understanding of the field. Furthermore, the selection of studies included in this review was guided by their availability to us and our own judgments on relevance and quality. Also, despite being systematic, this process is naturally subject to human error.

In spite of these limitations, we believe this review provides valuable insights into current research on interventions to combat online health misinformation and outlines important areas for future investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; methodology, J.M. and D.T.G.; software, J.M. and D.T.G.; validation, J.M., D.T.G., F.G.-d.-S., H.A. and A.D.; formal analysis, J.M., D.T.G.; investigation, J.M., D.T.G.; resources, J.M., D.T.G.; data curation, J.M., D.T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M., D.T.G.; writing—review and editing, J.M., D.T.G., F.G.-d.-S., H.A. and A.D.; visualization, J.M. and D.T.G.; supervision, F.G.-d.-S., H.A. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support and resources provided by the Institute of Global Innovation of the Imperial College London, which were instrumental in the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

To obtain a comprehensive list of relevant studies, we have decided to break down the concept of “source credibility labels” into three elements: the subject (“source”), the content (“credibility”), and the object (“label”). We then identified the following list of related terms:

- Source, origin, author, publisher, creator, influencer.

- Credibility, trustworthiness, reliability, validity, believability, accuracy, reputation, expertise, credible, trust, reliable, valid, believable, accurate, reputable, expert.

- Label, rating, certification, tick, evaluation, assessment, scheme, trustmark, mark, seal, endorsement, attestation, verified, grade, ranking, standard, badge.

By expanding the search to the terms above, we reduce the risk of missing relevant studies on specific interventions.

This resulted in the following Boolean search string for this particular key concept:

((“source” OR “origin” OR “author” OR “publisher” OR “creator” OR “influencer”)

AND

(“credibility” OR “trustworthiness” OR “reliability” OR “validity” OR “believability” OR “accuracy” OR “reputation” OR “expertise” OR “credible” OR “trust” OR “reliable” OR “valid” OR “believable” OR “accurate” OR “reputable” OR “expert”)

AND

(“label” OR “rating” OR “certification” OR “tick” OR “evaluation” OR “assessment” OR “scheme” OR “trustmark” OR “mark” OR “seal” OR “endorsement” OR “attestation” OR “verified” OR “grade” OR “ranking” OR “standard” OR “badge”))

This search string combines the terms related to each element (“source,” “credibility,” and “label”) using the OR operator within each group. The AND operator is used to connect the three groups together. Using this search string, we ensured the retrieval of articles that include any combination of these terms within the same document.

In relation to misinformation, we considered diverse alternative terms, resulting in the following search string:

(misinformation OR disinformation OR “conspiracy theories” OR ((false OR misleading OR inaccurate OR unreliable OR deceptive OR fabricated OR unsubstantiated OR incorrect OR unverified OR distorted OR fallacious OR fictitious OR misleading OR deceitful OR fake) AND (information OR news OR facts OR data OR claims OR content)))

In relation to “online information”, we considered diverse terms, resulting the following search string:

((online OR internet OR “web-based” OR digital OR “social media” OR influencers OR websites) AND (“health information OR health data OR health news OR diabetes OR vaccines OR virus OR information OR news”)) OR “e-health” OR “m-health”)

We combined these into a unique search string that was used at PubMed:

((“source” OR “origin” OR “author” OR “publisher” OR “creator” OR “influencer”) AND (“credibility” OR “trustworthiness” OR “reliability” OR “validity” OR “believability” OR “accuracy” OR “reputation” OR “expertise” OR “credible” OR “trust” OR “reliable” OR “valid” OR “believable” OR “accurate” OR “reputable” OR “expert”) AND (“label” OR “rating” OR “certification” OR “tick” OR “evaluation” OR “assessment” OR “scheme” OR “trustmark” OR “mark” OR “seal” OR “endorsement” OR “attestation” OR “verified” OR “grade” OR “ranking” OR “standard” OR “badge”)) AND (misinformation OR disinformation OR “conspiracy theories” OR ((false OR misleading OR inaccurate OR unreliable OR deceptive OR fabricated OR unsubstantiated OR incorrect OR unverified OR distorted OR fallacious OR fictitious OR misleading OR deceitful OR fake) AND (information OR news OR facts OR data OR claims OR content))) AND ((online OR internet OR “web-based” OR digital OR “social media” OR influencers OR websites) AND (“health information” OR “health data” OR “health news” OR “diabetes” OR “vaccines” OR “virus” OR information OR news OR “e-health” OR “m-health”))

The search strings used for the other databases were similar but adjusted based on each database’s specific search requirements.

The search strategy was designed to be comprehensive and systematic to ensure the identification of all the relevant literature. Using relevant keywords and Boolean operators helped narrow the search results to only those articles that were directly related to the research question. The inclusion of multiple electronic databases helped to ensure the identification of all the relevant literature.

Appendix B

| Studies: | Is It Clear in the Study What Is the “Cause” and What Is the “Effect” (i.e., There Is No Confusion about Which Variable Comes First)? | Were the Participants Included in Any Comparisons Similar? | Were the Participants Included in any Comparisons Receiving Similar Treatment/Care, Other than the Exposure or Intervention of Interest? | Was There a Control Group? | Were There Multiple Measurements of the Outcome Both Pre and Post the Intervention/Exposure? | Was Follow Up Complete and If Not, Were Differences between Groups in Terms of Their Follow Up Adequately Described and Analyzed? | Were the Outcomes of Participants Included in any Comparisons Measured in the Same Way? | Were Outcomes Measured in a Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | Total Number of Yes % | Risk of Bias * |

| (Bates et al. 2007) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 77.78% | Low |

| (Barker et al. 2010) | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | N/A | N/A |

| (Westerwick et al. 2017) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 77.78% | Low |

| (Bea-Muñoz et al. 2016) | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | N/A | N/A |

| (Jongenelis et al. 2018) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 88.89% | Low |

| (Borah and Xiao 2018) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% | Low |

| (Boutron et al. 2019) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 77.78% | Low |

| (Adams et al. 2020) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100.00% | Low |

| (Zhang et al. 2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 88.89% | Low |

| (Giese et al. 2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 88.89% | Low |

| (Zhang et al. 2022) | Yes | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Non applicable | Yes | Yes | 100.00% | Low |

| (Folkvord et al. 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Non applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 88.89% | Low |

| (Vu and Chen 2023) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Non applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | 88.89% | Low |

| * Low risk of bias >70%; moderate risk of bias 40–70%; high risk of bias <40%. The percentage was calculated according to how many “yes” responses each study received relative to the applicable items. | |||||||||||

References

- About-Media Bias/Fact Check. 2023. Available online: https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/about/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Adams, Clive E., Alan A. Montgomery, Tony Aburrow, Sophie Bloomfield, Paul M. Briley, Ebun Carew, Suravi Chatterjee-Woolman, Ghalia Feddah, Johannes Friedel, Josh Gibbard, and et al. 2020. Adding evidence of the effects of treatments into relevant Wikipedia pages: A randomised trial. BMJ Open 10: e033655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkisson, Richard V. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. The Social Science Journal 45: 700–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, Edoardo, Ritin Fernandez, Christina M. Godfrey, Cheryl Holly, Hanan Khalil, and Patraporn Tungpunkom. 2015. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13: 132–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslett, Kevin, Andrew M. Guess, Richard Bonneau, Jonathan Nagler, and Joshua A. Tucker. 2022. News credibility labels have limited average effects on news diet quality and fail to reduce misperceptions. Science Advances 8: eabl3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, Vimala, Wei Zhen Ng, Mun Chong Soo, Gan Joo Han, and Choon Jiat Lee. 2022. Infodemic and fake news—A comprehensive overview of its global magnitude during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021: A scoping review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 78: 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Sarah, Nathan P. Charlton, and Christopher P. Holstege. 2010. Accuracy of Internet Recommendations for Prehospital Care of Venomous Snake Bites. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 21: 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsaiyan, Sunil, and Charu Sijoria. 2021. Twitter Blue Tick—A Study of its Impact on Society. Indian Journal of Marketing 51: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Benjamin R., Sharon M. Romina, and Rukhsana Ahmed. 2007. The effect of improved readability scores on consumers’ perceptions of the quality of health information on the internet. Journal of Cancer Education 22: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bea-Muñoz, Manuel, María Medina-Sánchez, and M. T. Flórez-García. 2016. Quality of websites with patient information about spinal cord injury in Spanish. Spinal Cord 54: 540–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, Porismita, and Xizhu Xiao. 2018. The Importance of ‘Likes’: The Interplay of Message Framing, Source, and Social Endorsement on Credibility Perceptions of Health Information on Facebook. Journal of Health Communication 23: 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutron, Isabelle, Romana Haneef, Amélie Yavchitz, Gabriel Baron, John Novack, Ivan Oransky, Gary Schwitzer, and Philippe Ravaud. 2019. Three randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of “spin” in health news stories reporting studies of pharmacologic treatments on patients’/caregivers’ interpretation of treatment benefit. BMC Medicine 17: 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, Celia, Mark Selby, J.-R. Scherrer, and Ron D. Appel. 1998. The Health on the Net Code of Conduct for medical and health Websites. Computers in Biology and Medicine 28: 603–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Eileen. 2020. Logically Launches Tool to Identify and Combat Fake News ahead of US Elections|ZDNET. Available online: https://www.zdnet.com/article/logically-launches-tool-to-identify-and-combat-fake-news-ahead-of-us-elections/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Combatting Misinformation on Instagram|Instagram. 2019. Available online: https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/combatting-misinformation-on-instagram (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Eurostat. 2022. Consumption of Online News Rises in Popularity. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220824-1 (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Eurostat. 2023. Households-Level of Internet Access. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/167d07c9-479a-4587-8961-0f100c09ed8d?lang=en (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Folkvord, Frans, Freek Snelting, Doeschka Anschutz, Tilo Hartmann, Alexandra Theben, Laura Gunderson, Ivar Vermeulen, and Francisco Lupiáñez-Villanueva. 2022. Effect of Source Type and Protective Message on the Critical Evaluation of News Messages on Facebook: Randomized Controlled Trial in the Netherlands. Journal of Medical Internet Research 24: e27945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, Helge, Hansjörg Neth, and Wolfgang Gaissmaier. 2021. Determinants of information diffusion in online communication on vaccination: The benefits of visual displays. Vaccine 39: 6407–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongenelis, Michelle I., Simone Pettigrew, Melanie Wakefield, Terry Slevin, Iain S. Pratt, Tanya Chikritzhs, and Wenbin Liang. 2018. Investigating Single- Versus Multiple-Source Approaches to Communicating Health Messages Via an Online Simulation. American Journal of Health Promotion 32: 979–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledderer, Loni, Marianne Kjær, Emilie Kirstine Madsen, Jacob Busch, and Antoinette Fage-Butler. 2020. Nudging in Public Health Lifestyle Interventions: A Systematic Literature Review and Metasynthesis. Health Education & Behavior 47: 749–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhortykh, Mykola, Aleksandra Urman, and Roberto Ulloa. 2020. How search engines disseminate information about COVID-19 and why they should do better. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review: May 2020, Volume 1, Special Issue on COVID-19 and Misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marecos, João, and Francisco de Abreu Duarte. 2022. A right to lie in the age of disinformation: Protecting free speech beyond the first amendment. In Media Literacy, Equity, and Justice. Edited by Belinha S. De Abreu. New York: Routledge, pp. 206–13. [Google Scholar]

- Marecos, João, Ethan Shattock, Oliver Bartlett, Francisco Goiana-da-Silva, Hendramoorthy Maheswaran, Hutan Ashrafian, and Ara Darzi. 2023. Health misinformation and freedom of expression: Considerations for policymakers. Health Economics, Policy and Law 18: 204–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and Prisma Group. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, Garrett, Briony Swire-Thompson, Jessica Montgomery Polny, Matthew Kopec, and John P. Wihbey. 2022. The emerging science of content labeling: Contextualizing social media content moderation. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 73: 1365–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our Synthetic and Manipulated Media Policy|X Help. 2023. Available online: https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/manipulated-media (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Pornpitakpan, Chanthika. 2004. The Persuasiveness of Source Credibility: A Critical Review of Five Decades’ Evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34: 243–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prike, Toby, Lucy H. Butler, and Ullrich K. H. Ecker. 2024. Source-credibility information and social norms improve truth discernment and reduce engagement with misinformation online. Scientific Reports 14: 6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, Matilda White, Carl I. Hovland, Irving L. Janis, and Harold H. Kelley. 1954. Communication and Persuasion: Psychological Studies of Opinion Change. American Sociological Review 19: 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothkopf, David. 2003. When the Buzz Bites Back. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2003/05/11/when-the-buzz-bites-back/bc8cd84f-cab6-4648-bf58-0277261af6cd/ (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Seiler, Roger, and Gunther Kucza. 2017. Source credibility model, source attractiveness model and match-up-hypothesis: An integrated model. Journal of International Scientific Publications: Economy & Business 11: 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Rory, Kung Chen, Daisy Winner, Stefanie Friedhoff, and Claire Wardle. 2023. A Systematic Review Of COVID-19 Misinformation Interventions: Lessons Learned: Study examines COVID-19 misinformation interventions and lessons learned. Health Affairs 42: 1738–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Lledo, Victor, and Javier Alvarez-Galvez. 2021. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23: e17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swire-Thompson, Briony, and David Lazer. 2020. Public Health and Online Misinformation: Challenges and Recommendations. Annual Review of Public Health 41: 433–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Behavioural Science Report. 2021. UN Innovation Network. Available online: https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6241324b2f22ec56f2f9109a/6436c5424b5cb1b634feeac3_UN%20BeSci%20Report%202021%20vFF.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Vu, Hong Tien, and Yvonnes Chen. 2023. What Influences Audience Susceptibility to Fake Health News: An Experimental Study Using a Dual Model of Information Processing in Credibility Assessment. Health Communication 39: 1113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Website Rating Process and Criteria—NewsGuard. 2023. Available online: https://www.newsguardtech.com/ratings/rating-process-criteria/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Westerwick, Axel, Benjamin K. Johnson, and Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick. 2017. Change Your Ways: Fostering Health Attitudes Toward Change Through Selective Exposure to Online Health Messages. Health Communication 32: 639–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2022. Toolkit for Tackling Misinformation on Noncommunicable Disease: Forum for Tackling Misinformation on Health and NCDs. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, D. Adeline, Miguel I. Gómez, and Harry M. Kaiser. 2019. Signaling impacts of GMO labeling on fruit and vegetable demand. PLoS ONE 14: e0223910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jingwen, Jieyu Ding Featherstone, Christopher Calabrese, and Magdalena Wojcieszak. 2021. Effects of fact-checking social media vaccine misinformation on attitudes toward vaccines. Preventive Medicine 145: 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yuqi, Bin Guo, Yasan Ding, Jiaqi Liu, Chen Qiu, Sicong Liu, and Zhiwen Yu. 2022. Investigation of the determinants for misinformation correction effectiveness on social media during COVID-19 pandemic. Information Processing & Management 59: 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).