Adapting Traditional Media to the Social Media Culture: A Case Study of Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Τhe Network Theory of Power: A World Transformed by Globalization and Information Technology

1.2. The Role of Media and Technology in Political Communication

1.3. Journalism as a Pillar of Political Communication in the Era of Social Media

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

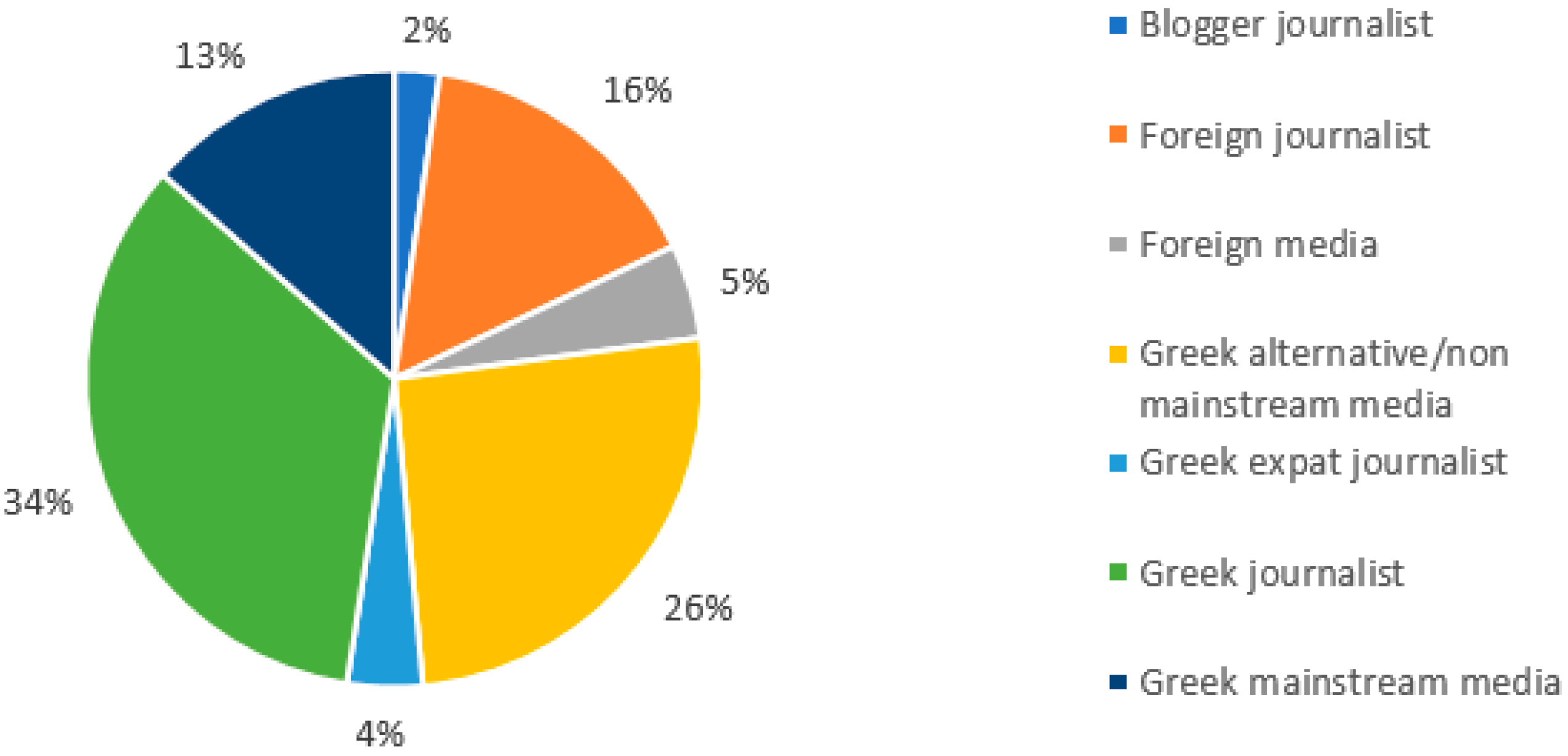

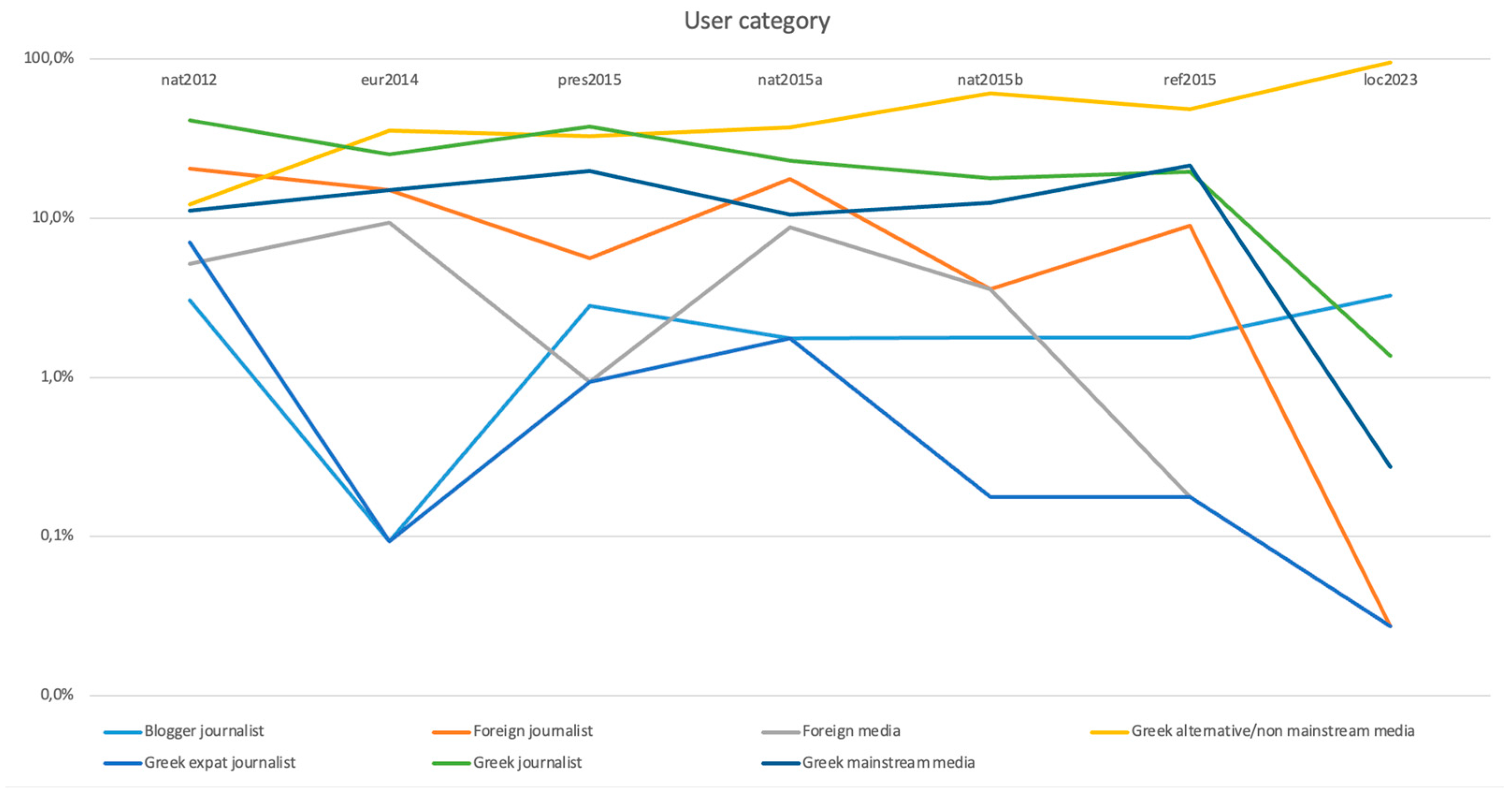

3.1. The User Categories of the Messages

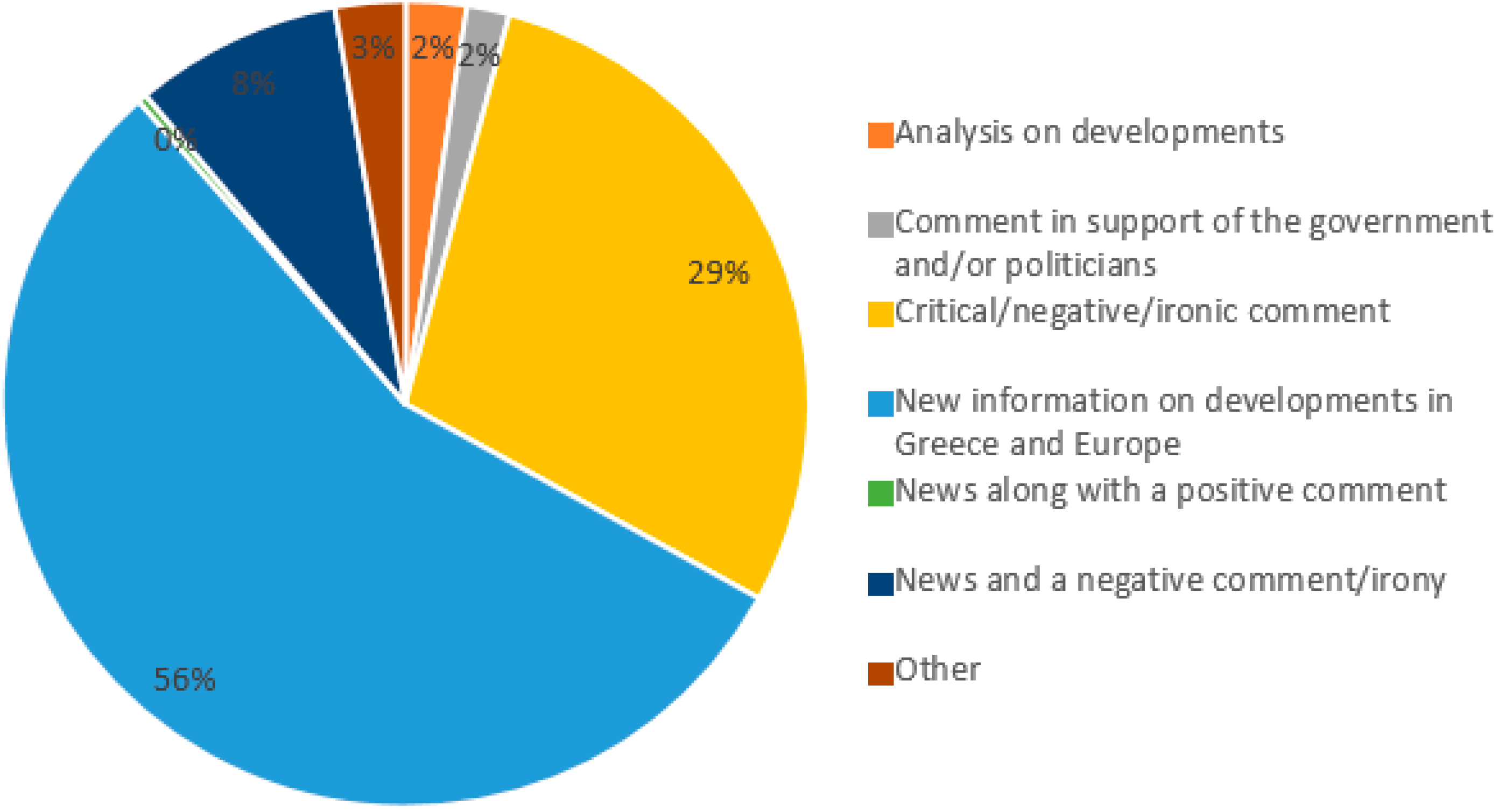

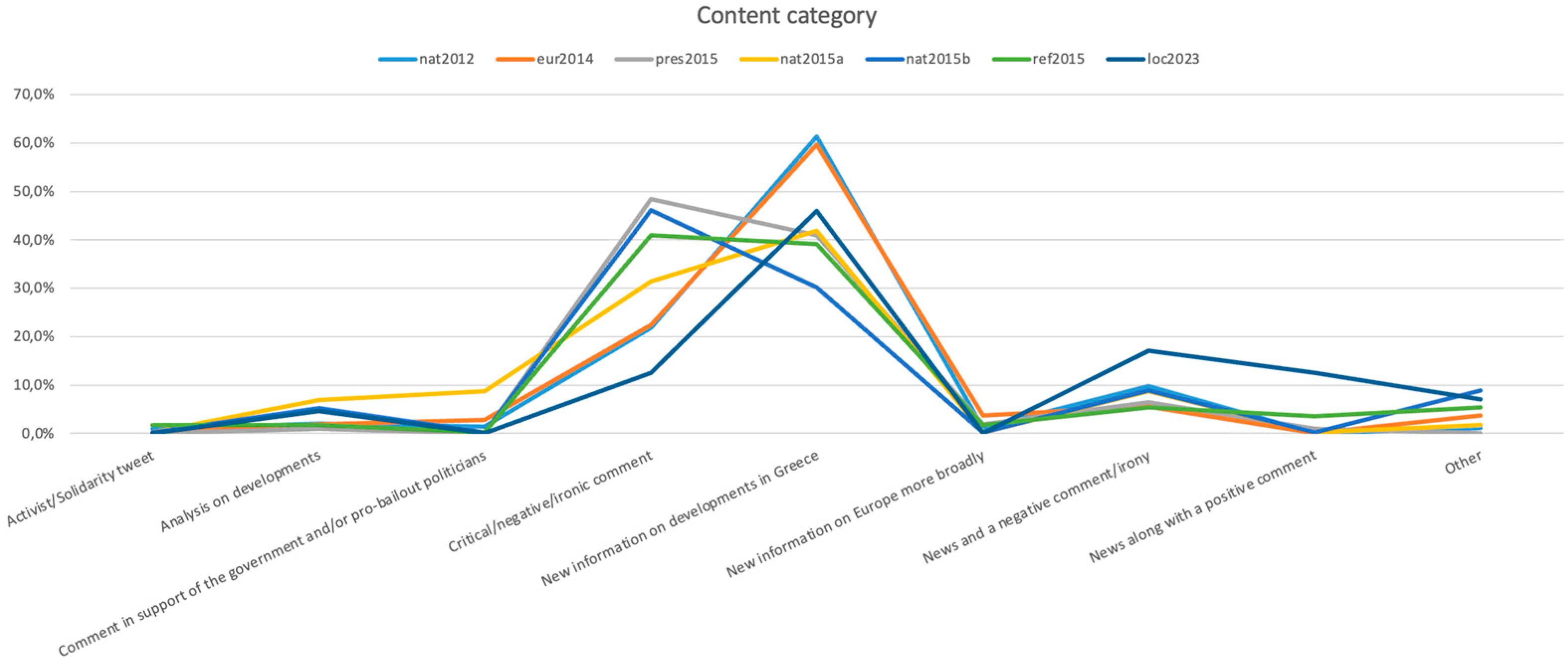

3.2. The Content of the Messages

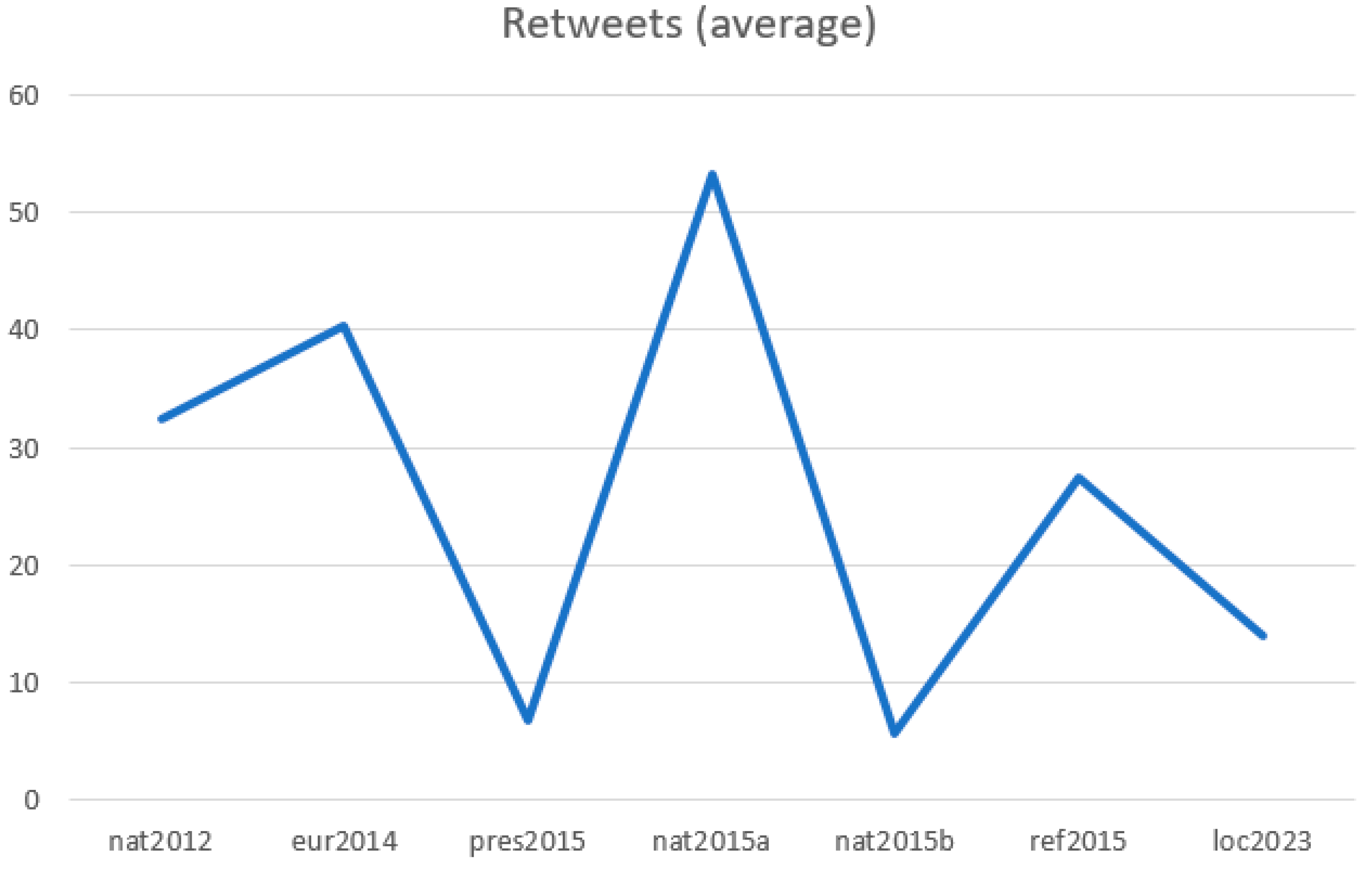

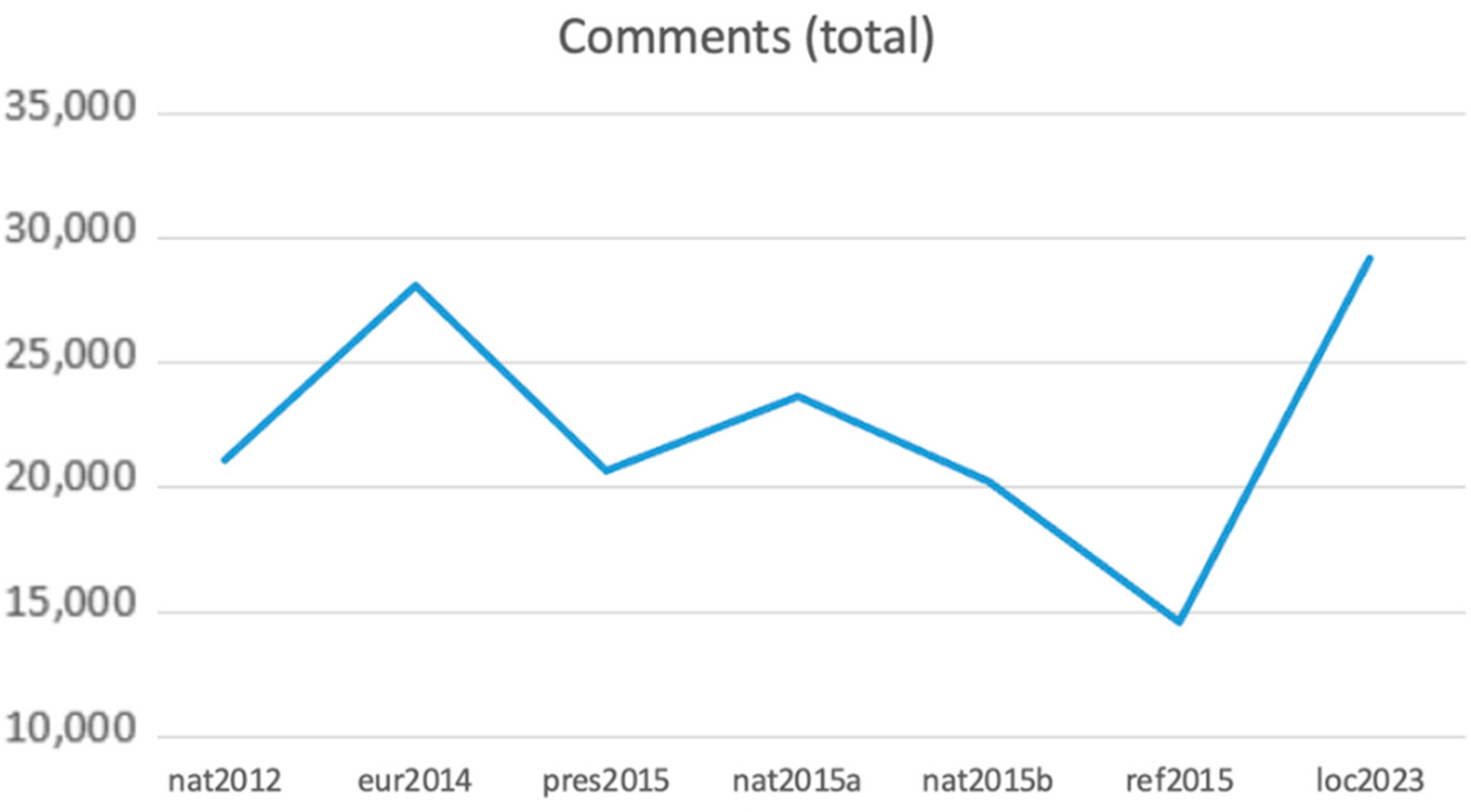

3.3. Followers, Follows, Retweets and Favorites

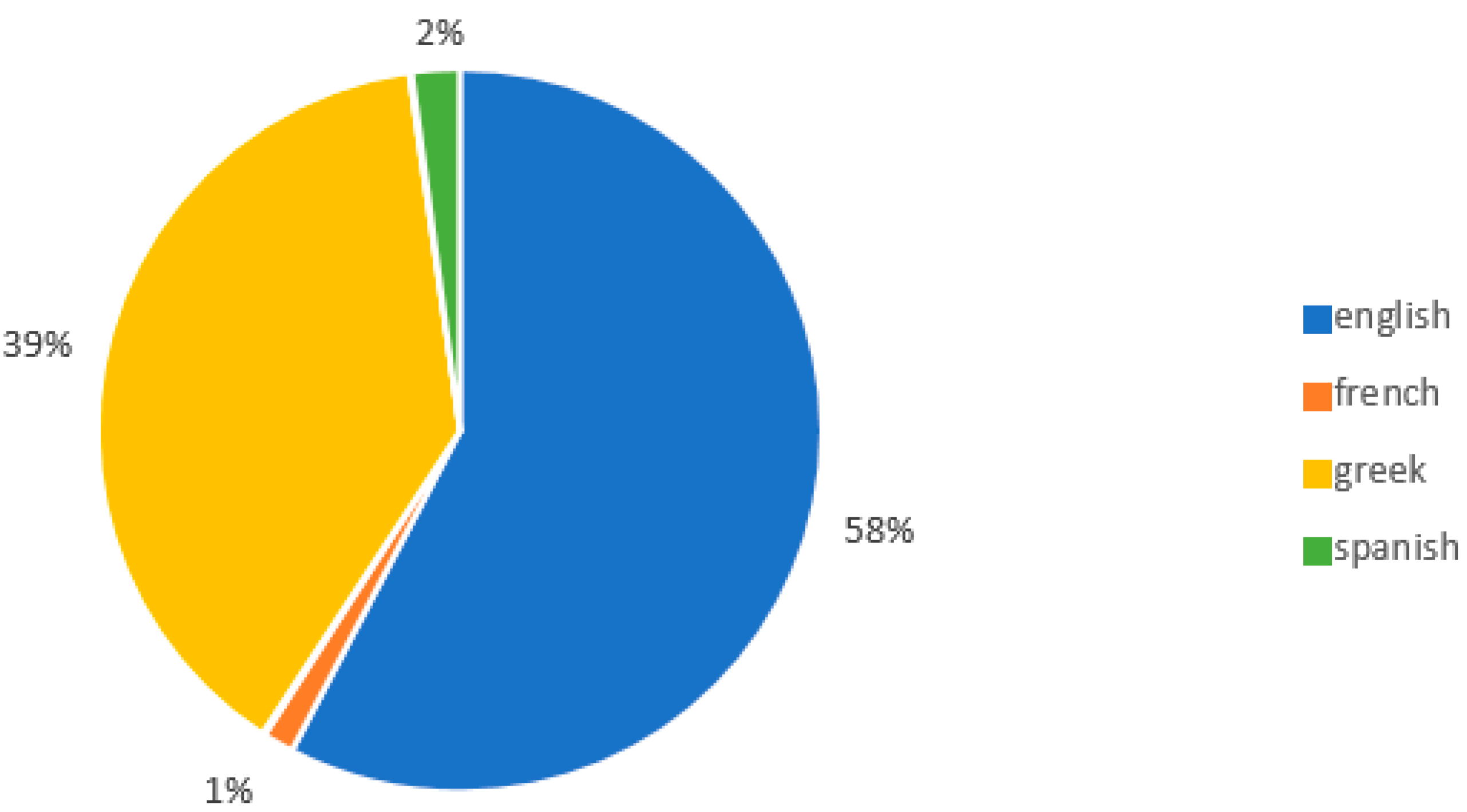

3.4. Language of Communication

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anttiroiko, Ari-Veikko. 2015. Castells’ network concept and its connections to social, economic and political network analyses. Journal of Social Structure 16: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artwick, Claudette. 2013. Reporters on Twitter: Product or service? Digital Journalism 1: 212–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 1996. The space of flows. In The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 376–482. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 2010. Globalisation, networking, urbanisation: Reflections on the spatial dynamics of the information age. Urban Studies 47: 2737–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2011. Network theory|A network theory of power. International Journal of Communication 5: 15. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 2013. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 2015. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. Available online: https://voidnetwork.gr/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Networks-of-Outrage-and-Hope-Social-Movements-in-the-Internet-Age-Manuel-Castells.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power, 1st ed. Oxford Studies in Digital Politics. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Feng, and Nathan Yang. 2010. Twitter in congress: Outreach vs. transparency. Social Sciences 1: 1–10. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/23597/ (accessed on 5 March 2024). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davis, Richard. 1999. The Web of Politics: The Internet’s Impact on the American Political System. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demertzis, Maria, Hallett Andrew Hughes, and Rummel Ole. 2000. Is the European Union a natural currency area, or is it held together by policy makers? Review of World Economics 136: 657–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demertzis, Nicolas. 2013. Emotions in Politics. The Affect Dimension in Political Tension. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioltzidou, Georgia, and Fotini Gioltzidou. 2022. Generation as a key factor in the diversity of journalistic cultures in Greece. In SHS Web of Conferences. Les Ulis: EDP Sciences, vol. 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioltzidou, Georgia, Dossis Michael, Chrysafis Theodoros, Mylona Ifigeneia, Gioltzidou Fotini, and Amanatidis Dimitrios. 2024a. The role of hashtags in Social Networks: The case of social mobilization in Greece. Paper presented at the 8th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Piraeus, Greece, November 10–12; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioltzidou, Georgia, Gioltzidou Fotini, and Chrysafis Theodoros. 2024b. Political Communication in the Digital Age: The Case of Social Media. [Γιολτζίδου Γεωργία, Γιολτζίδου Φωτεινή, & Χρυσάφης Θεόδωρος. 2024. H Πολιτική Επικοινωνία στην ψηφιακή εποχή: H περίπτωση των Κοινωνικών Μέσων]. Ετήσιο Ελληνόφωνο Επιστημονικό Συνέδριο Εργαστηρίων Επικοινωνίας 2: 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Dan, and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, Alfred. 2010. Twittering the news: The emergence of ambient journalism. Journalism Practice 4: 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, Avery, and Seth Lewis. 2011. Journalists, social media, and the use of humor on Twitter. Electronic Journal of Communication 21: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, Pascal, Jungherr Andreas, and Schoen Harald. 2011. Small worlds with a difference: New gatekeepers and the filtering of political information on Twitter. Paper presented at 3rd International Web Science Conference, Koblenz, Germany, June 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Cherubini Federica, and Newman Nic. 2016. The Future of Online News Video. Digital News Project, ISBN 978-1-907384-21-9. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2882465 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Lasorsa, Dominic, Seth C. Lewis, and Avory Holton. 2012. Normalizing Twitter: Journalism practice in an emerging communication space. Journalism Studies 13: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotan, Gilad, Graeff Erhardt, Ananny Mike, Gaffney Devin, and Pearce Ian. 2011. The Arab Spring|the revolutions were tweeted: Information flows during the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. International Journal of Communication 5: 31. Available online: http://ijoc.org (accessed on 10 December 2015).

- McNair, Brian. 1998. The Sociology of Journalism. New York: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, Brian. 2017. An Introduction to Political Communication. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis, vol. 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Nic, Fletcher Richard, Schulz Anne, Andi Simge, Robertson Craig, and Nielsen Rasmus Kleis. 2021. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3873260 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Norris, Pippa. 2000. Democratic divide? The impact of the Internet on parliaments worldwide. American Political Science Association Panel 2: 195–240. [Google Scholar]

- Siapera, Eugenia. 2017. Reclaiming citizenship in the post-democratic condition. Journal of Citizenship and Globalisation Studies 1: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Soriano, Manuel Torres. 2013. Internet as a Driver of Political Change: Cyber-pessimists and Cyber-optimists. Revista del Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos 1: 332–52. Available online: https://www.ugr.es/~gesi/internet-political-change.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1994. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 273–85. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP, Africa. 2016. Africa Human Development Report 2016 Accelerating Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Africa. No. 267638. United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/AfHDR_2016_lowres_EN.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Varol, Onur, and Ismail Uluturk. 2019. Journalists on Twitter: Self-branding, audiences, and involvement of bots. Journal of Computational Social Science 3: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolton, Dominique. 1990. Political communication: The construction of a model. European Journal of Communication 5: 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrella, Daniel. 2009. The Social Media Marketing Book. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Zayani, Mohamed. 2021. Digital journalism, social media platforms, and audience engagement: The case of AJ+. Digital Journalism 9: 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1st Period | 2nd Period | 3rd Period | 4th Period | 5th Period | 6th Period | 7th Period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From…to | 6 May–17 June 2012 | 30 April–25 May 2014 | 25 December 2014–11 January 2015 | 30 December 2014–25 January 2015 | 21 August–27 September 2015 | 28 June–12 July 2015 | 1–16 October 2023 |

| Description | National elections, 2012 | European elections, 2014 | Presidential elections, 2015 | National elections, January 2015 | National elections, September 2015 | Referendum, 2015 | Municipal elections, 2023 |

| Popular #hashtags | #ekloges, #ekloges2012, #Greece2012, #ekloges12 | #EP2014, #EP14 | #PtD | #ekloges2015 | #ekloges, #ekloges2015_round2 | #Greekreferendum, #grefenderum, #greferendum, #dimopsifisma | #δημοτικεςεκλογες2023, #δημοτικες2023, #εκλογες2023, #ekloges2023 |

| Number of tweets | 6287 | More than 100,000 | 6412 | 38,325 | 94,017 | 77,717 | 1512 |

| Followers | Follows | Retweets | Favorites | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 3794.78 | 2052.38 | 46.23 | 0.10 |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Maximum | 517,568 | 306,879 | 3803 | 9 |

| Followers | Follows | Retweets | Favorites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek traditional mass media | Mean | 40,767.13 | 348.74 | 15.62 | 0.11 |

| Minimum | 76 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 337,352 | 2699 | 534 | 3 | |

| non-Greek traditional mass media | Mean | 21,929.63 | 1200.00 | 47.67 | 0.0 |

| Minimum | 701 | 338 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 127,345 | 1979 | 496 | 0 | |

| Greek and non-Greek, alternative/non-traditional media | Mean | 19,018.01 | 2505.37 | 13.63 | 0.16 |

| Minimum | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 517,568 | 30,724 | 767 | 2 |

| Followers | Follows | Retweets | Favorites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek journalists | Mean | 4275.66 | 2422.26 | 21.81 | 0.14 |

| Minimum | 31 | 67 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 51,864 | 28,957 | 1483 | 3 | |

| non-Greek journalists | Mean | 11,969.83 | 1324.57 | 58.55 | 0.09 |

| Minimum | 18 | 38 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 83,921 | 4281 | 1034 | 1 | |

| Greek journalists living abroad | Mean | 1104.00 | 612.50 | 41.97 | 0.0 |

| Minimum | 1084 | 600 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 1124 | 625 | 720 | 0 | |

| blogger journalists | Mean | 5323.67 | 2460.67 | 52.79 | 0.0 |

| Minimum | 84 | 117 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 28,495 | 10,013 | 393 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gioltzidou, G.; Mitka, D.; Gioltzidou, F.; Chrysafis, T.; Mylona, I.; Amanatidis, D. Adapting Traditional Media to the Social Media Culture: A Case Study of Greece. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 485-499. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020032

Gioltzidou G, Mitka D, Gioltzidou F, Chrysafis T, Mylona I, Amanatidis D. Adapting Traditional Media to the Social Media Culture: A Case Study of Greece. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(2):485-499. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020032

Chicago/Turabian StyleGioltzidou, Georgia, Dimitra Mitka, Fotini Gioltzidou, Theodoros Chrysafis, Ifigeneia Mylona, and Dimitrios Amanatidis. 2024. "Adapting Traditional Media to the Social Media Culture: A Case Study of Greece" Journalism and Media 5, no. 2: 485-499. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020032

APA StyleGioltzidou, G., Mitka, D., Gioltzidou, F., Chrysafis, T., Mylona, I., & Amanatidis, D. (2024). Adapting Traditional Media to the Social Media Culture: A Case Study of Greece. Journalism and Media, 5(2), 485-499. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020032