Fans, Fellows or Followers: A Study on How Sport Federations Shape Social Media Affordances

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Aim

- RQ1: What are the incentives for sport federations to use social media?

- RQ2: In what way do sport federations shape their social media affordances through their strategic work with communication on social media?

- RQ3: How do sports federations perceive—and interact with—their social media audiences?

1.2. Theoretical Framework

The affordances of the environment are what It offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either good or ill. The verb to afford is found in the dictionary, the noun affordance is not. I have made it up. I mean by it something that refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does. It implies the complementary of the animal and the environment.

“Social media affordances are the perceived actual or imagined properties of social media, emerging through the relation of technological, social, and contextual, that enable and constrain specific uses of the platforms”.

“The point is not solely what people think technology can do or what designers say technology can do, but what people imagine a tool is for. Imagination connotes perception, not just rationality, a distinction that is missing in how communication scholars currently use the term “affordance.”.

1.3. Mediatization and Sports

1.4. The Swedish Sports Movement

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Sample Selection

| Federation | Formed Year | Number of Member Associations | Number of Individual Members | Gender Distribution among Members | Number of Staff Members |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Swedish Equestrian Federation | 1912 | 841 | 168,599 | 92% female 8% male | 41 (33 female 8 male) |

| The Swedish Basketball Federation | 1952 | 321 | 142,516 | 45% female 55% male | 19 (6 female 13 male) |

| The Swedish Skateboard Association | 2012 | 100 | 29,796 | 22% female 78% male | 4 (1 female 3 male) |

2.1.2. Interviews

2.1.3. Digital Ethnography

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. The Federation’s Social Media Affordances

3.1.1. Aims of Using Social Network Sites

Marc: If we look at one of the challenges that we face … is that we want to keep young players involved in basketball. We don’t want young people who play basketball to stop playing because other things get in the way. We cannot fully succeed in this unless we have a brand and communication channels that appeal to and interest the young audience. Because the probability of staying in the sport is much greater if they see that we stand for interesting content, an interesting brand, and interesting content on social media. There you can draw inspiration from many different sources. For example, the NBA in the US has done a fantastic job with that. They have been at the forefront of digital development all along and have worked very successfully in raising player profiles and engaging young fans in an extremely effective way.(Interview with Marc, SBF)

Lisa: I also think that we are a bit behind, we operate in a very old-fashioned way in general. So, when we make strategies for different projects and communication plans, we don’t always think social, but things are starting to happen. If you have a pile of money, you should put at least half of it to buy outreach if you want to reach out properly. Because it’s not possible to rely on organic outreach anymore. So that there is, of course, a development potential in that as well. To think more social in our plans and strategies.Lovisa: Why do you think it’s so old-fashioned in your sport?Lisa: Honestly, I think there are a lot of good people … but we are such a super analog industry. I don’t think it has anything to do with age either, there are also young people who become analog like that. There’s sort of a strength in it as well, but it lags a bit. You do what you’ve always done.…Maybe we’re a bit slower than others because we have a bit slower sport, I don’t really know, because we are very hands-on as well.(Interview with Lisa, SEF)

3.1.2. The Federations’ Choice of Social Network Sites

| Federation | TikTok | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Swedish Equestrian Federation | 66,000 followers | 76,300 followers | 3600 followers | - |

| The Swedish Basketball Federation | 10,700 followers | 17,500 followers | 5160 followers | 9600 followers |

| The Swedish Skateboard Association | 3400 group members | 3170 followers | - | - |

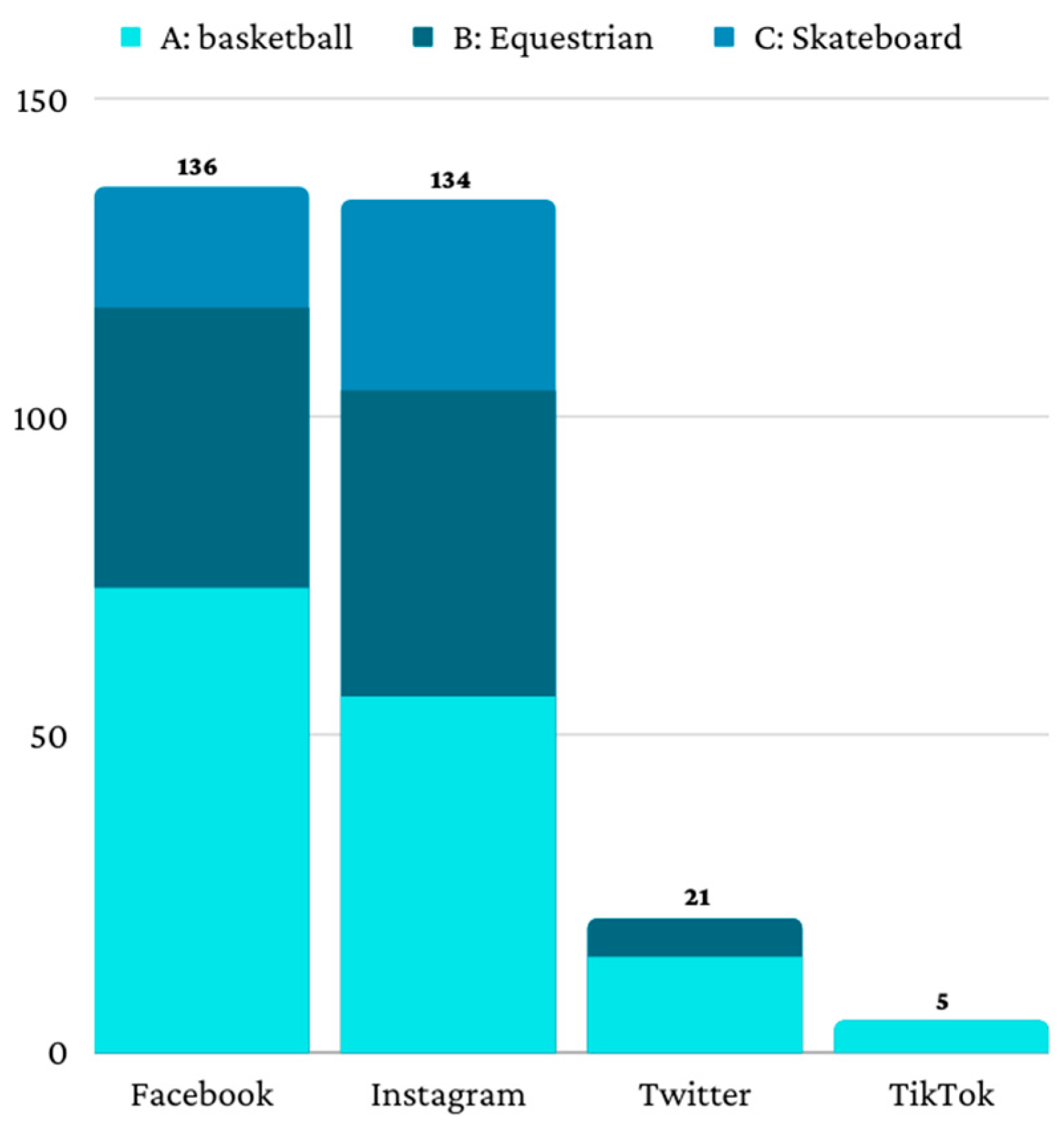

| A: Basketball | B: Equestrian | C: Skateboard | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Facebook | 73 | 44 | 19 |

| 2: Instagram | 56 | 48 | 30 |

| 3: TikTok | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 4: Twitter | 15 | 6 | 0 |

| Total | 148 | 92 | 49 |

3.1.3. Background and Traditions

Jessie: I think that a sport that has been part of the Swedish Sports Confederation for a long time has its pathway already set out. They’re probably like, it has always been like this, it’s not questioned. I think that for us, who attract people who are not used to the way things are in the organized sports movement or understand what it’s about, communication on social media is important.(Interview with Jessie, SSA)

Lisa: We sort of feel like we don’t want to be everywhere (on all different social media platforms, authors remark) and we don’t need to be the first ones present at a new platform. We still must be able to keep up with the work, so we haven’t been very keen on starting up all new platforms at the same time. There is a huge potential that we just don’t really have time for today.(Interview with Lisa, SEF)

3.2. The Federation’s Uses of Social Media

3.2.1. Social Media Strategies

Sam: We don’t want to overload our channels, we managed to do that...not last Friday but the Friday before that. Then it was just like, on our Facebook, I just, what happened now? There were like six posts on the same day, which meant that the most important thing that we needed to communicate that day was just lost and got fewer likes or lost integration, what is it called?Lovisa: Outreach?Sam: Yes, it just drowned because there was so much else that came up and then we had to have a meeting at the office, and just talk about, what happened now? I want us to post a lot of stuff, but you must have a bit of structure. So, check the page before you blurt things out. But it’s learning by doing, of course.(Interview with Sam, SSA)

3.2.2. Content Produced by the Federations

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| 1: Support to associations | Posts containing information to associations and updates from associations |

| 2: Competition | Posts related to competitions, such as news and updates on results and information about rules |

| 3: Elite sports | Posts related to elite sports and elite athletes |

| 4: Games and activites | Posts introducing online activities or games, such as quizzes |

| 5. Influencers and profiles | Posts introducing individual influencers and profiles, such as athletes or profiles connected to the federation |

| 6. Knowledge exchange | Posts raising knowledge in relation to the federation or the sport in general |

| 7. Media | Posts forwarding content from other media channels |

| 8. News and updates | Posts containing official information and/or news from the federation |

| 9. Social initiatives and projects | Posts containing information on noncompetitive initiatives and projects |

| 10. Collaboration and sponsors | Posts containing information and updates from sponsors and partners |

3.2.3. Tone and Language

Lisa: For example, we have a strategy around never answering with a name, for our employees, we get quite a lot of angry comments like that, it’s a bit unpleasant. There have been a few trolls throughout the years who have targeted individual employees. So, it’s probably mostly to avoid that kind of harassment and stuff, this is where we need our policies.Lovisa: I’m a bit curious, why do you have this strategy, of never answering with your names?Lisa: In general, Facebook has probably succeeded better, I don’t really know this, but I feel it that way because we notice a significant difference in how they clean, very rough words and such. Because people get very angry. It could, for example, be about changing a rule, or moving a competition, it can be things like that where people want to reach individuals and decision-makers (at the federation, authors remark). It can be harsh words too, now maybe it’s not so much towards individuals right now, at the moment it’s more that we are stupid in general. Haha.…Sometimes if it’s a spokesperson or our sports director for example, then, of course, it can happen that they go after individual employees, and we’d rather not have that of course. We are happy to respond to it collectively and sometimes the power of a chairman’s words or something is needed, but we do not want to put individuals in vulnerable positions.(Interview with Lisa, SEF)

Sam: … it’s a very important role that we need to translate the sports confederation’s words into words that are relevant and can be received by the associations and practitioners. In some cases, we may not always use the term sport, it is important that we replace it with skateboarding. There must not be too many complicated bureaucratic words going on. The text needs to be … for example, when we communicate with municipalities we use a certain language, it is important that we can speak their language too but when we talk to the associations, we say the same thing but translated … it’s not like they don’t understand anything of what we say. It’s not like that, it’s more about the fact that certain words may have a negative connotation for some and then we can just replace that word with something that is more relevant within the scene (the skateboard scene, authors remark). Then it is received better.(Interview with Sam, SSA)

3.3. The Federation’s Perceptions and Interactions with Their Users

3.3.1. Target Groups

Marc: … Regarding social media, it is a combination of these target groups, but we try to adapt the content on social media to appeal to the external target group to a greater extent. So that we reach those who are not yet very into basketball. So, I would probably sum it up that the strategy is to start from those of us who already are important target groups in basketball in Sweden, but we also try to attract target groups outside who can be seen as future basketball consumers.(Interview with Marc, SBF)

Lisa: … when we think of social media channels, we don’t make such a big difference between members and non-members. We want more members, and we want more people to be interested in our federation, and the organized equestrian sport. So, we think we should be as generous and open as we can.Lovisa: Okay, I have a follow-up question, could you please rank these target groups?Lisa: Oh yes..the associations. It’s the associations, those who are elected representatives in the associations, and those who are involved and run them, they are of course most important to us. But it really is very different over time, what stakeholders in society are most relevant. But traditionally we work via the associations, and then their members, first the organization and then the individual member. Then we have, media, media is quite prioritized.(Interview with Lisa, SEF)

Sam: We work very much on gender equality and inclusion in the skateboard federation. However, the typical skateboard practitioner is white, young- or middle-aged men, at least in Sweden, so we work a lot on bringing awareness that we welcome everyone and that we want to have fifty-fifty girls and boys. We want to promote a diversity of skateboarders because it’s still a very “white sport”, we know that … we’re at least aware of it. Something that is very interesting is that we’ve gotten some input from a few of the “middle-aged white men” that they don’t really feel included as we mainly focus on female- and LGBTQ practitioners in our communication for example in our social media channels.(Interview with Sam, SSA)

3.3.2. Opportunities with SNS

Marc: Basketball In the future as I see it … If our ambition is to build basketball partly through connecting sports to fashion, music, and all that … if we want to succeed in that then social media will be crucial to get where we want to go. We want basketball to stand for more than just the sporting aspect and more seen as a cool and societal phenomenon … a force. We will be able to do that much better by using social media … So that’s where we see a lot of potential. It’s connected to the fact that we see our sport as a brand that includes more than just the games and the players. It’s a brand connected to what they do off the arena and connected to general things. Basketball promotes integration, equality, and inclusion. Tearing down walls in society is what we stand for. This can be communicated in a completely different way through social media than we would otherwise would’ve been able to and that is fantastic.(Interview with Marc, SBF)

4. Concluding Discussion

5. Research Limitation and Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersson, Urlika. 2003. Sportens Olika Sidor: Männens Och de Manliga Sporternas Revir. 2003 års publicistiska bokslut. Göteborg: Inst. för Journalistik och Masskommunikation. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Martin. 2015. Netnografi. Att Forska om och Med Internet. Lund: Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, Andrew C., Ryan M. Broussard, Qingru Xu, and Mingming Xu. 2019. Untangling International Sport Social Media Use: Contrasting U.S. and Chinese Uses and Gratifications across Four Platforms. Communication and Sport 7: 630–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkner, Thomas, and Daniel Nölleke. 2016. Soccer Players and Their Media-Related Behavior: A Contribution on the Mediatization of Sports. Communication and Sport 4: 367–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, Svend, and Steinar Kvale. 2018. Doing Interviews, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, David. 2009. Skate Perception: Self-Representation, Identity, and Visual Style in a Youth Subculture. In Video Cultures: Media Technology and Everyday Creativity. Edited by David Buckingham and Rebekah Willet. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 133–51. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Victoria, and Virginia Braun. 2018. Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: A critical reflection. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 18: 107–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corden, Anne, and Roy Sainsbury. 2006. Using Verbatim Quotations in Reporting Qualitative Social Research: Researchers’ Views. York: Social Policy Research Unit, University of York. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, David, and James Stanyer. 2014. Mediatization: Key concept or conceptual bandwagon? Media, Culture and Society 36: 1032–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, Tyler. 2020. Authentic Subcultural Identities and Social Media: American Skateboarders and Instagram. Deviant Behavior 41: 649–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, Peter. 2021. Australian Sports Journalism: Power, Control and Threats. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- English, Peter. 2022. Sports Newsrooms Versus In-House Media: Cheerleading and Critical Reporting in News and Match Coverage. Communication & Sport 10: 854–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fahlén, Josef, and Cecilia Stenling. 2016. Sport policy in Sweden. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 8: 515–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, Kevin, Daneil Lock, and Adam Karg. 2015. Sport and social media research: A review. Sport Management Review 18: 166–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, Kirsten. 2016. Sports organizations in a new wave of mediatization. Communication and Sport 4: 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurin, Andrea. N. 2017. Elite female athletes’ perceptions of new media use relating to their careers: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sport Management 31: 345–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, James J. 1979. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, Brett, and David Rowe. 2012. Sport beyond Television: The Internet, Digital Media and Networked Media Sport. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, Sonia, and Peter Lunt. 2014. Mediatization: An Emerging Paradigm for Media and Communication Research? Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundby, Knut. 2014. Mediatization of Communication. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Manzerolle, Vincent, and Michael Daubs. 2021. Friction-free authenticity: Mobile social networks and transactional affordances. Media Culture & Society 43: 1279–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, Shaun. 2013. Media, Place and Mobility. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, Siegfried, Torsten Schlesinger, Emmanuel Bayle, and David Giaugue. 2015. Professionalisation of sport federations—A multi-level framework for analysing forms, causes and consequences. European Sport Management Quarterly 14: 407–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Peter, and Gina Neff. 2015. Imagined Affordance: Reconstructing a Keyword for Communication Theory. Social Media + Society 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nölleke, Daniel, and Thomas Birkner. 2019. Bypassing traditional sports media? Why and how professional volleyball players use social networking sites. Studies in Communication, Media 8: 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, Johan R. 2011. A contract reconsidered? Changes in the Swedish state’s relation to the sports movement. International Journal of Sport Policy 3: 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oczki, Jarosław, and Weronika Pleskot. 2020. Financing a basketball club in Poland—The case of Twarde Pierniki S.A. Journal of Physical Education & Sport 20: 1050–54. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Thomas. 2008. The Professionalization of Sport in the Scandinavian Countries. Idrottsforum. Available online: http://www.idrottsforum.org/articles/peterson/peterson080220.html (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Riksidrottsförbundet. 2021. Idrotten i siffror. Available online: https://www.rf.se/download/18.407871d3183abb2a6131d8f/1665068212883/2021%20Idrotten%20i%20siffror%20-%20RF.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Ronzhyn, Alexander, Ana Sofia Cardenal, and Batlle Albert Rubio. 2022. Defining affordances in social media research: A literature review. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallhorn, Christina, Daniel Nölleke, Philip Sinner, Christof Seeger, Jörg-Uwe Nieland, Thomas Horky, and Katja Mehler. 2022. Mediatization in Times of Pandemic: How German Grassroots Sports Clubs Employed Digital Media to Overcome Communication Challenges During COVID-19. Communication & Sport 10: 891–912. [Google Scholar]

- Secular, Steven. 2019. Hoop Streams: The Rise of the NBA, Multiplatform Television and Sports as Media Content, 1982 to 2015. Santa Barbara: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Adrienne. 2017. Encoding and decoding affordances: Stuart Hall and interactive media technologies. Media, Culture & Society 39: 592. [Google Scholar]

- Skey, Michael, Chris Stone, Olu Jenzen, and Anita Mangan. 2018. Mediatization and Sport: A Bottom-Up Perspective. Communication & Sport 6: 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorell, Gabriella, and Susanna Hedenborg. 2015. Riding instructors, gender, militarism, and stable culture in Sweden: Continuity and change in the twentieth century. International Journal of the History of Sport 32: 650–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treem, Jeffrey W., and Paul. M. Leonardi. 2013. Social Media Use in Organizations: Exploring the Affordances of Visibility, Editability, Persistence, and Association. Annals of the International Communication Association 36: 143–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welander, Johan. 2020. Idrottsrörelsens Ledarskap och Organisering 2030, en Framtidsspaning om Professionalisering och Idrotten som Arbetsgivare. Stockholm: Riksidrottsförbundet. [Google Scholar]

- Westelius, Alf, Ann-Sofie Westelius, and Erik Lundmark. 2012. Idrott, föreningar, sociala medier och kommunikation, en undersökning av IT-användning inom idrottsrörelsen. FOU 2012:2. Available online: https://www.rf.se/download/18.7e76e6bd183a68d7b7114d8/1664975899258/FOU2012_2%20Idrott,%20f%C3%B6reningar,%20sociala%20media%20och%20kommunikation.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Woermann, Niklas. 2012. On the Slope Is on the Screen: Prosumption, Social Media Practices, and Scopic Systems in the Freeskiing Subculture. American Behavioral Scientist 56: 618–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Broms, L. Fans, Fellows or Followers: A Study on How Sport Federations Shape Social Media Affordances. Journal. Media 2023, 4, 688-709. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4020044

Broms L. Fans, Fellows or Followers: A Study on How Sport Federations Shape Social Media Affordances. Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(2):688-709. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4020044

Chicago/Turabian StyleBroms, Lovisa. 2023. "Fans, Fellows or Followers: A Study on How Sport Federations Shape Social Media Affordances" Journalism and Media 4, no. 2: 688-709. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4020044

APA StyleBroms, L. (2023). Fans, Fellows or Followers: A Study on How Sport Federations Shape Social Media Affordances. Journalism and Media, 4(2), 688-709. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4020044