Understanding Motivations for Plural Identity on Facebook among Nigerian Users: A Uses and Gratification Perspective for Engaging on Social Network Sites (SNS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Identity and Plurality

2.2. Theoretical Basis and Existing Empirical Studies on Plural Identity

2.3. Use and Gratification Theory and Related Works

2.4. Communicative Behaviors on Social Media

2.4.1. Presentation of the Extended Self

2.4.2. Self-Expression

2.4.3. Social Obligation

2.4.4. Social Support

2.4.5. Social Interaction

2.5. Social Media and Identity

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Data

3.2. Procedure and Sampling

3.3. Measures

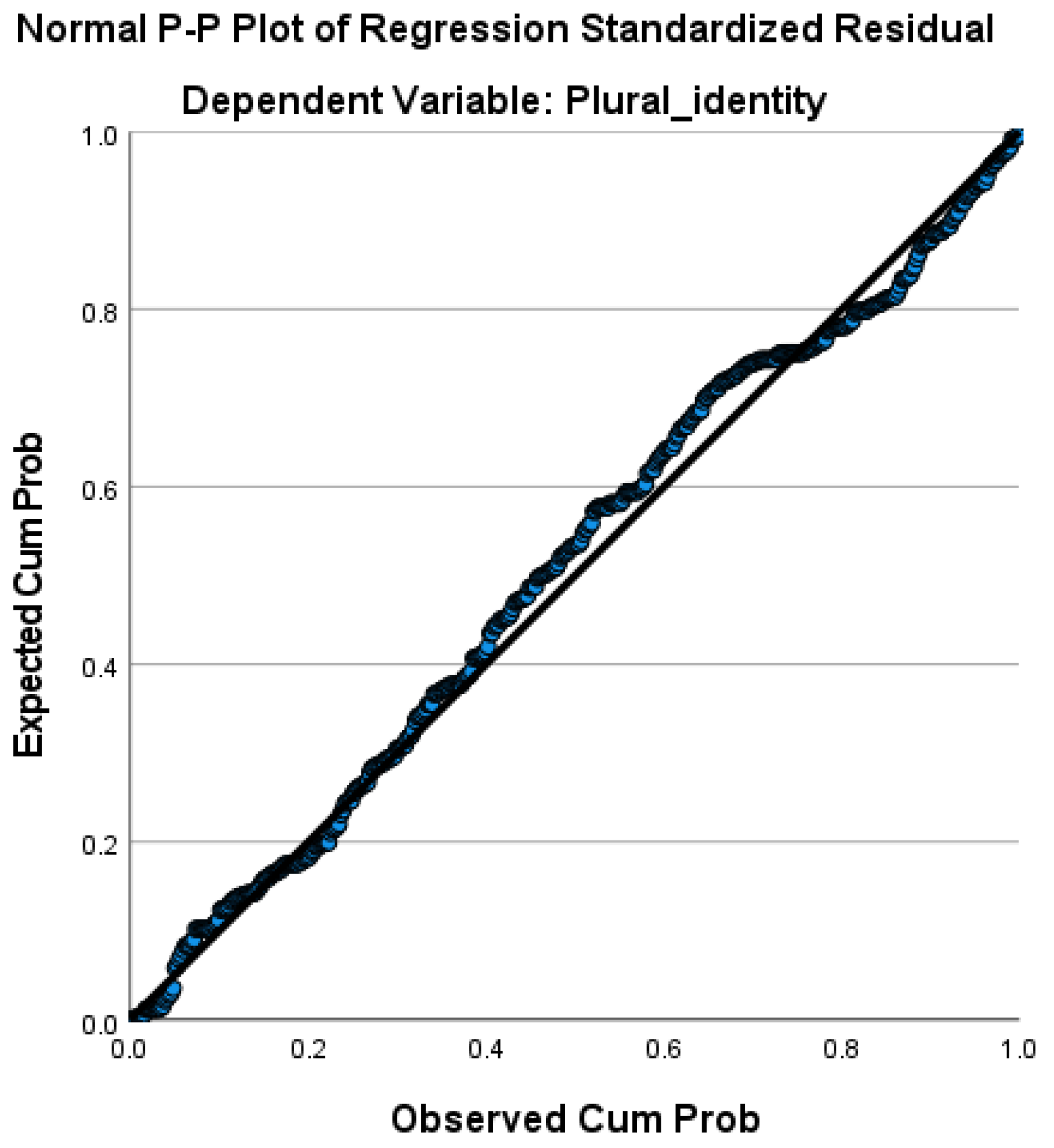

4. Results

5. Discussion

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, Amit, and Durga Toshniwal. 2019. SmPFT: Social media based profile fusion technique for data enrichment. Computer Networks 158: 123–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, Ibrahim M., Sadiq M. Sohail, and Nelson O. Ndubisi. 2015. Understanding the usage of global social networking sites by Arabs through the lens of uses and gratifications theory. Journal of Service Management 26: 662–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russel W. 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 139–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russel W. 2013. Extended self in a digital world. Journal of Consumer Research 40: 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. 2016. The social construction of reality. In Social Theory Re-Wired. New York: Routledge, pp. 110–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 1991. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17: 475–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, David. 2008. Introducing Identity. MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, Vivien. 2003. An Introduction to Social Constructionism, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisir, Fethi, Levent Atahan, and Mirary Saracoglu. 2013. Factors affecting social network sites usage on smartphones of students in Turkey. Paper presented at the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science, San Francisco, CA, USA, October 23–25, vol. 2, pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cerulo, Karen A. 2011. Social interaction: Do non-humans count? Sociology Compass 5: 775–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Simon. 2008. Culture and identity. In The Sage Handbook of Cultural Analysis. London: Sage, pp. 510–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakes, Sheridan J., and Lyndall Steed. 2009. SPSS: Analysis without Anguish Using SPSS Version 14.0 for Windows. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Colás Bravo, Pilar M., Teresa González Ramírez, and Juan De Pablos Pons. 2013. Young people and social networks: Motivations and preferred uses. Comunicar 40: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curras-Perez, Rafael, Carla Ruiz-Mafe, and Silvia Sanz-Blas. 2014. Determinants of user behavior and recommendation in social networks: An integrative approach from the uses and gratifications perspective. Industrial Management & Data Systems 114: 1477–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Choudhury, Munmun, and Emre Kiciman. 2017. The language of social support in social media and its effect on suicidal ideation risk. Paper presented at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Montreal, QC, Canada, May 15–18, vol. 11, pp. 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux, Kay. 1992. Personalizing identity and socializing self. In Social Psychology of Identity and the Self-Concept. Edited by Glynis M. Breakwell. London: Surrey University Press, pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMicco, Joan Morris, and David R. Millen. 2007. Identity management: Multiple presentations of self in Facebook. Paper presented at the 2007 International ACM Conference on Supporting Group Work, Sanibel Island, FL, USA, November 4–7; pp. 383–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Erikson H. 1968. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, Russel H., Edwin A. Effrein, and Victoria J. Falender. 1981. Self-perceptions following social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 41: 232–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Eileen, and Rebecca A. Reuber. 2011. Social interaction via new social media:(How) can interactions on Twitter affect effectual thinking and behavior? Journal of Business Venturing 26: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1989. The ego and the id (1923). Tacd Journal 17: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, John P., James S. DeLo, Merna D. Galassi, and Sheila Bastien. 1974. The college self-expression scale: A measure of assertiveness. Behavior Therapy 5: 165–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergen, Kenneth J. 1981. The functions and foibles of negotiating self-conception. In Self-Concept: Advances in Theory and Research. Edited by Mervin D. Lynch, Ardyth A. Norem-Hebeisen and Kenneth J. Gergen. Ballinger. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, Kenneth J., and Mary M. Gergen. 2000. The new aging: Self construction and social values. In Social Structures and Aging. New York: Springer, pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 2009. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: DoubledayAnchor. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F. 2011. Multivariate data analysis: An overview. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science. London: Springer, pp. 904–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Michael Page, and Niek Brunsveld. 2019. Essentials of Business Research Methods. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stanley G. 1972. Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education. Washington: Appleton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, Susan. 2015. The Construction of the Self: Developmental and Sociocultural Foundations. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, Michael L. 1993. 2002—A research odyssey: Toward the development of a communication theory of identity. Communication Monographs 60: 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, Michael L., Michael Hecht, Ronald L. Jackson, and Sidney A. Ribeau. 2003. African American Communication: Exploring Identity and Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, Michael L., Jennifer R. Warren, Eura Jung, and Janice L. Krieger. 2005. A communication theory of identity: Development, theoretical perspective, and future directions. In Theorizing about Intercultural Communication. Edited by William B. Gudykunst. New York: Sage, pp. 257–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppler, Sarah Susanna, Robin Segerer, and Jana Nikitin. 2022. The Six Components of Social Interactions: Actor, Partner, Relation, Activities, Context, and Evaluation. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 743074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janoff-Bulman, Ronnie, and Hallie K. Leggatt. 2002. Culture and social obligation: When “shoulds” are perceived as “wants”. Journal of Research in Personality 36: 260–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourard, Sidney M. 1964. The Transparent Self: Self-Disclosure and Well-Being. Princeton: Van Nostrand Reinhold. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Eura. 2011. Identity gap: Mediator between communication input and outcome variables. Communication Quarterly 59: 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Eura, and Michael L. Hecht. 2004. Elaborating the communication theory of identity: Identity gaps and communication outcomes. Communication Quarterly 52: 265–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Hyunjin, and Wonsun Shin. 2021. When Facebook becomes a part of the self: How do motives for using Facebook influence privacy management? Frontiers in Psychology 12: 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Andreas M., and Michael Haenlein. 2010. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons 53: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Elihu, Michael Gurevith, and Hadassah Haas. 1973. On the use of the mass media for important things. American Sociological Review 38: 164–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Heejung S., and Aimee Drolet. 2003. Choice and self-expression: A cultural analysis of variety-seeking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85: 373–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Heejung S., and Deborah Ko. 2007. Culture and self-expression. In The Self. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 325–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Heejung S., and David K. Sherman. 2007. “Express yourself”: Culture and the effect of self-expression on choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Dorinne. 1990. Crafting Selves: Power, Gender, and Discourses of Identity in a Japanese Workplace. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Law Insider. n.d. Social Obligation Defined. Available online: https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/social-obligations#:~:text=Social%20Obligations%20means%20any%20common (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Lee, Yeunjae. 2020. Motivations of employees’ communicative behaviors on social media: Individual, interpersonal, and organizational factors. Internet Research 30: 971–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xiaoqian, Wenhong Chen, and Pawel Popiel. 2015. What happens on Facebook stays on Facebook? The implications of Facebook interaction for perceived, receiving, and giving social support. Computers in Human Behavior 51: 106–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, James E. 1966. Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 3: 551–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel, and Ziva Kunda. 1986. Stability and malleability of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 858–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel, and Elissa Wurf. 1987. The dynamic self-concept: A social psychological perspective. Annual Review of Psychology 38: 299–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, William J., and Claire V. McGuire. 1982. Significant others in self-space: Sex differences and developmental trends in the social self. In Psychological Perspectives on the Self. Edited by Jerry Suls. Hillsdale: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, Denis. 1987. Mass Communication Theory: An Introduction, 2nd ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Moir, Lance. 2001. What do we mean by corporate social responsibility? Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 1: 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, Serge. 1984. The phenomena of social representations. In Social Representations. Edited by Robert M. Farr and Serge Moscovici. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Taewoo. 2014. Technology use and work-life balance. Applied Research in Quality of Life 9: 1017–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nario-Redmond, Michelle R., Monica Biernat, Scott Eidelman, and Debra J. Palenske. 2004. The social and personal identities scale: A measure of the differential importance ascribed to social and personal self-categorizations. Self and Identity 3: 143–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, Clifford, Brian Jeffrey Fogg, and Youngme Moon. 1996. Can computers be teammates? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 45: 669–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, Clifford, and Youngme Moon. 2000. Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers. Journal of Social Issues 56: 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedenthal, Paula M., and Denise R. Beike. 1997. Interrelated and isolated self-concepts. Personality and Social Psychology Review 1: 106–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Sanghee, and Sue Yeon Syn. 2015. Motivations for sharing information and social support in social media: A comparative analysis of Facebook, Twitter, Delicious, YouTube, and Flickr. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 66: 2045–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, Aida Shekh, Wan Edura Wan Rashid, and Afiza Abdul Majid. 2014. Motivations for using social networking sites on quality work life. Paper presented at 4th International Conference on Marketing and Retailing 2013 (INCOMAR 2013), Holiday Inn Glennmarie, Selangor, Malaysia, December 3–4, vol. 130, pp. 524–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, Daphna. 1993. The lens of personhood: Viewing the self, others, and conflict in a multicultural society. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65: 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, Marie, Ana Cueva Navas, Ana S. Mattila, and Hubert B. Van Hoof. 2017. An investigation into Facebook “liking” behavior: An exploratory study. Social Media+ Society 3: 2056305117706785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, Julie. 2020. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step-by-Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, James W., Janice K. Kiecolt-Glaser, and Ronald Glaser. 1988. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: Health implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 56: 239–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocchi, Nicola, Anu Asnaani, Alejandra Piquer Martinez, Ashwini Nadkarni, and Stefan G. Hofmann. 2015. Differences between people who use only Facebook and those who use Facebook plus Twitter. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 31: 157–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2022. Global Population Projected to Exceed 8 Billion in 2022; Half Live in Just Seven Countries. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/07/21/global-population-projected-to-exceed-8-billion-in-2022-half-live-in-just-seven-countries/#:~:text=Global%20population%20projected%20to%20exceed,live%20in%20just%20seven%20countries&text=The%20world’s%20population%20will%20cross,live%20in%20just%20seven%20countries (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Reis, Harry T., John Nezlek, and Ladd Wheeler. 1980. Physical attractiveness in social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38: 604–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Mario S., and Sheldon Cohen. 1998. Social support. Encyclopedia of Mental Health 3: 535–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schaetti, Barbara F. 2015. Identity. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Intercultural Competence. Edited by Janet M. Bennett. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, pp. 405–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, Helana, Rens Scheepers, Rosemary Stockdale, and Nurdin Nurdin. 2014. The dependent variable in social media use. Journal of Computer Information Systems 54: 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 2007. Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny. India: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Guosong. 2009. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Research 19: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbourne, Cathy D., and Anita L. Stewart. 1991. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine 32: 705–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, Thomas F., Marla Royne Stafford, and Lawrence L. Schkade. 2004. Determining uses and gratifications for the Internet. Decision Sciences 35: 259–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. 2022. December 19. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/ (accessed on 19 December 2002).

- Suler, John R. 2002. Identity management in cyberspace. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 4: 455–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, Keith S. 2018. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Research in Science Education 48: 1273–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri. 1978. The achievement of group differentiation. In Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by Henri Tajfel. London: Academy Press, pp. 77, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1979. An integrative theory of social conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by W. Austin and S. Worchel. Monterey: Brooks-Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Ting-Toomey, Stella. 2015. Identity negotiation theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Communication. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, Harry C. 1989. The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review 96: 506–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, Harry C. 1990. Cross-cultural studies of individualism and collectivism. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Edited by John J. Berman. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, vol. 37, pp. 41–133. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, John C. 1984. Social identification and psychological group formation. In The Social Dimension: European Developments in Social Psychology. Edited by Henri Tajfel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 2, pp. 518–38. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, John C., Michael A. Hogg, Penelope J. Oakes, Steven D. Reicher, and Margaret S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Hoboken: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, John C., Penelope J. Oakes, S. Alexander Haslam, and Craig McGarty. 1994. Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 20: 454–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, Eric B. 2001. The functions of internet use and their social and psychological consequences. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 4: 723–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, Anita, and David Williams. 2013. Why people use social media: A uses and gratifications approach. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 16: 362–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, Duane. 2001. The future of corporate social responsibility. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis 9: 225–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Population Review. 2022. Africa Population 2022. December 19. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/continents/africa-population (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Xie, Yungeng, Rui Qiao, Guosong Shao, and Hong Chen. 2017. Research on Chinese social media users’ communication behaviors during public emergency events. Telematics and Informatics 34: 740–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Characteristics | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Nigerians | 429 | 100 |

| Active Facebook user | Yes | 429 | 100 |

| Belonging to Facebook groups | Yes | 408 | 95.1 |

| No | 21 | 4.9 | |

| Number of Facebook groups | 1 | 39 | 9.1 |

| 2 | 28 | 6.6 | |

| 3 | 48 | 11.2 | |

| 4 | 20 | 4.7 | |

| 5 or more | 292 | 68.3 | |

| 18 years old or above | 429 | 100 | |

| Age | 18–30 | 177 | 41.3 |

| 31–45 | 196 | 47.5 | |

| 46–60 | 49 | 11.4 | |

| 61+ | 7 | 1.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 241 | 56.2 |

| Female | 186 | 43.4 | |

| Non-binary | 1 | 0.2 | |

| I prefer not to say | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Educational Qualification | Elementary | 10 | 2.3 |

| Secondary | 52 | 12.1 | |

| Teacher training | 20 | 4.7 | |

| Any certification | 22 | 5.1 | |

| OND | 40 | 9.3 | |

| HND | 83 | 19.3 | |

| Bachelors | 139 | 32.4 | |

| Masters | 58 | 13.5 | |

| Doctorate | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Facebook weekly use | Rarely | 58 | 13.5 |

| Occasionally | 84 | 19.6 | |

| Sometimes | 54 | 12.6 | |

| Frequently | 107 | 24.9 | |

| Usually | 55 | 12.8 | |

| Every time | 71 | 16.6 |

| Variables | N | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Plural Identity | 429 | 4.47 | 0.91 | - | |||||

| 2 | Social Obligation | 429 | 4.58 | 1.57 | 0.56 ** | - | ||||

| 3 | Social Support | 429 | 5.03 | 1.48 | 0.58 ** | 0.65 ** | - | |||

| 4 | Social Interaction | 429 | 5.05 | 1.41 | 0.49 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.42 ** | - | ||

| 5 | Presentation of Extended Self | 429 | 4.68 | 1.41 | 0.61 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.46 ** | - | |

| 6 | Self-Expression | 429 | 4.46 | 1.13 | 0.66 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.74 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.60 ** | - |

| M1 | M2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | β | t | SE | β | t | |

| Age | 0.05 | −0.18 ** | −4.85 | 0.43 | −0.16 ** | −4.50 |

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.07 | 1.80 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.68 |

| Educational Qualification | 0.01 | 0.12 ** | 3.21 | 0.01 | 0.09 * | 2.60 |

| Social Obligation | 0.02 | 0.27 ** | 5.55 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 1.72 |

| Social Support | 0.03 | 0.29 ** | 6.0 | 0.03 | 0.11 * | 2.13 |

| Social Interaction | 0.02 | 0.26 ** | 6.38 | 0.02 | 0.16 ** | 3.90 |

| Presentation of Extended Self | 0.03 | 0.25 ** | 5.64 | |||

| Self-Expression | 0.05 | 0.28 ** | 4.86 | |||

| R2 | 0.48 | 0.55 | ||||

| F for change in R2 | 65.36 ** | 33.44 ** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullah, T.O.; Hale, B.J.; Lasisi, M.I. Understanding Motivations for Plural Identity on Facebook among Nigerian Users: A Uses and Gratification Perspective for Engaging on Social Network Sites (SNS). Journal. Media 2023, 4, 710-726. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030045

Abdullah TO, Hale BJ, Lasisi MI. Understanding Motivations for Plural Identity on Facebook among Nigerian Users: A Uses and Gratification Perspective for Engaging on Social Network Sites (SNS). Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(3):710-726. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030045

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Tawfiq Ola, Brent J. Hale, and Mutiu Iyanda Lasisi. 2023. "Understanding Motivations for Plural Identity on Facebook among Nigerian Users: A Uses and Gratification Perspective for Engaging on Social Network Sites (SNS)" Journalism and Media 4, no. 3: 710-726. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030045

APA StyleAbdullah, T. O., Hale, B. J., & Lasisi, M. I. (2023). Understanding Motivations for Plural Identity on Facebook among Nigerian Users: A Uses and Gratification Perspective for Engaging on Social Network Sites (SNS). Journalism and Media, 4(3), 710-726. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030045