Parenting on Celebrities’ and Influencers’ Social Media: Revamping Traditional Gender Portrayals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Celebrities and Influencers on Social Media

3. Gender, Private Life and Parenting

4. Platform Society

5. Methods

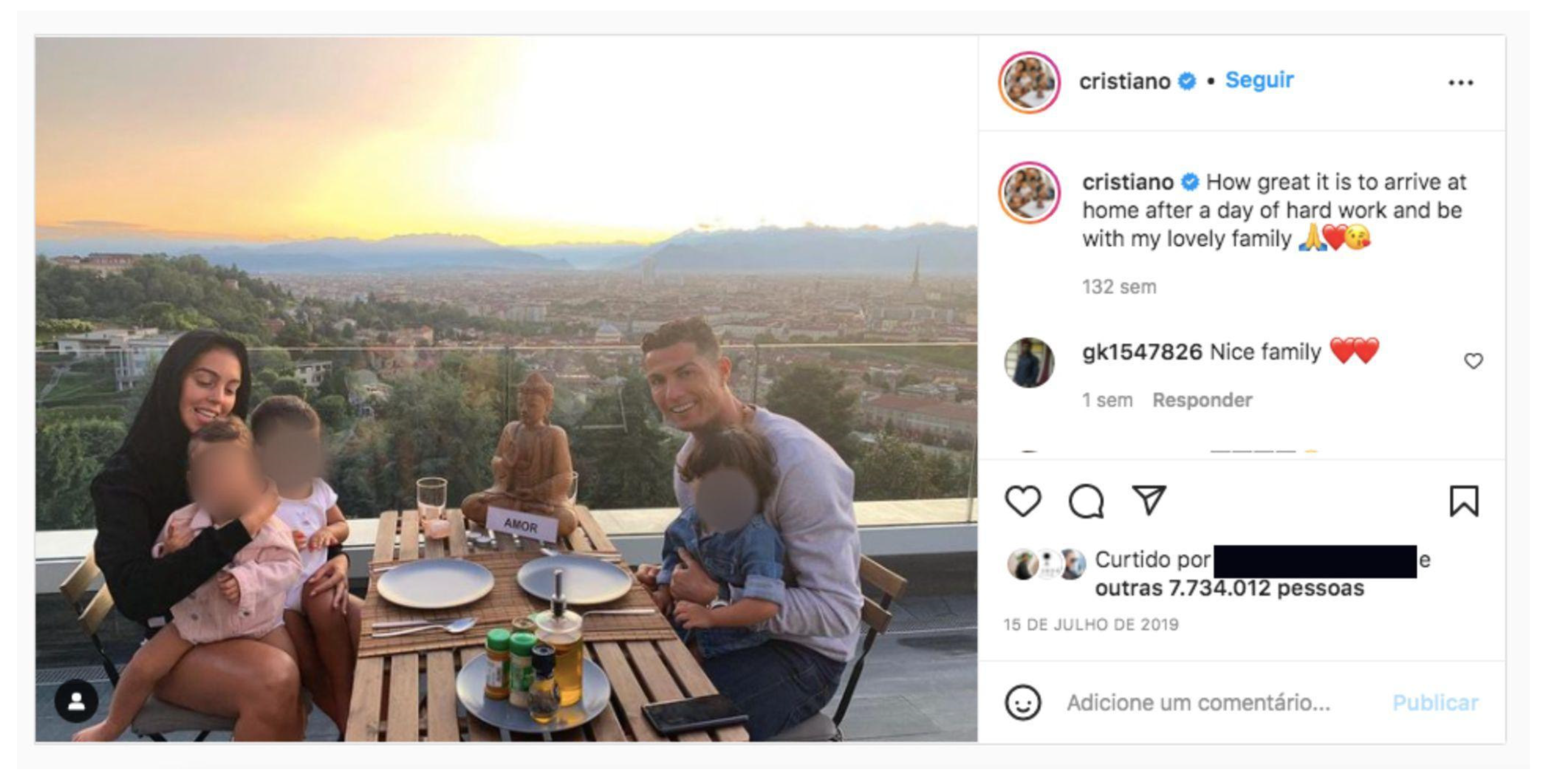

6. Analysis

6.1. General Findings of the Extensive Corpus

6.2. Parenting and Everyday Family Life

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | On Instagram, by number of followers, descending: Cristiano Ronaldo, André Silva, Pepe, Ricardo Quaresma, Bernardo Silva, António Raminhos, Nelson Semedo, André Gomes, Lourenço Ortigão, Diogo Piçarra (male); Sara Sampaio, Carolina Deslandes, Cristina Ferreira, Carolina Patrocínio, Rita Pereira, Dolores Aveiro, Bárbara Bandeira, Mafalda Sampaio, Liliana Filipa, and Carolina Loureiro (female). On YouTube, by number of followers, descending: Sir Kazzio, Dark Frame, Feromonas, Wuant, Windoh, Pi, Nuno Agonia, Tiagovski, João Sousa, RicFazeres (male); SEA3PO, Owhana, SofiaBBeauty, Inês Rochinha, Mafalda Sampaio, Catarina Filipe, Mafalda Creative, Angie Costa, A Inês Ribeiro, Bumba na Fofinha (female). |

| 2 | For instance, SirKazzio did not upload any video in the first three months of 2019, which he explained in a video entitled “What if I went back to doing this?…” (6 April 2019) as related to being too busy since the birth of his daughter. |

References

- Abidin, Crystal. 2015. Communicative 🧡 Intimacies: Influencers and Perceived Interconnectedness. Ada New Media 8. Available online: https://adanewmedia.org/2015/11/issue8-abidin/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Abidin, Crystal. 2019. Victim, Rival, Bully: Influencers’ Narrative Cultures Around Cyberbullying. In Narratives in Research and Interventions on Cyberbullying among Young People. Edited by Heidi Vandebosch and Lelia Green. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejevic, Mark. 2009. Exploiting YouTube: Contradictions of user-generated labor. In The YouTube Reader. Edited by Pelle Snickars and Patrick Vonderau. Stockholm: National Library of Sweden, pp. 406–23. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Catherine. 2019. How influencer ‘mumpreneur’ bloggers and ‘everyday’ mums frame presenting their children online. Media International Australia 170: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autenrieth, Ulla. 2018. Family photography in a networked age: Anti-sharenting as a reaction to risk assessment and behavior adaptation. In Digital Parenting: The Challenges for Families in the Digital Age. Edited by Giovanna Mascheroni, Cristina Ponte and Ana Jorge. Gothenburg: Nordicom, pp. 219–31. Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-12034 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Bakioğlu, Burku. S. 2018. Exposing convergence: YouTube, fan labour, and anxiety of cultural production in Lonelygirl15. Convergence 24: 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2018. Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, and Inna Arzumanova. 2012. Creative authorship, self-actualizing women, and the self-brand. In Media Authorship. Edited by Cynthia Chris and David A. Gerstner. London: Routledge, pp. 163–79. [Google Scholar]

- Baym, Nancy K. 2015. Connect with Your Audience! The Relational Labor of Connection. The Communication Review 18: 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Sophie. 2020. Algorithmic Experts: Selling Algorithmic Lore on YouTube. Social Media + Society 6: 205630511989732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Jean, and Darryl Woodford. 2014. Content Creation and Curation. In The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Jean, and Joshua Green. 2018. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Campana, Mario, Astrid Van den Bossche, and Bryoney Miller. 2020. #dadtribe: Performing Sharenting Labour to Commercialise Involved Fatherhood. Journal of Macromarketing 40: 475–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Raewyn W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic masculinity rethinking the concept. Gender and Society 19: 829–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, Nick, and Andreas Hepp. 2016. The Mediated Construction of Reality. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, Stuart, David Craig, and Jon Silver. 2016. YouTube, multichannel networks and the accelerated evolution of the new screen ecology. Convergence 22: 376–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, Sarah, Steven Eggermont, and Laura Vandenbosch. 2022. Instagram Influencers as Superwomen: Influencers’ Lifestyle Presentations Observed Through Framing Analysis. Media and Communication 10: 173–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, Brooke Erin, and Emily Hund. 2015. “Having it All” on Social Media: Entrepreneurial Femininity and Self-Branding Among Fashion Bloggers. Social Media + Society 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, Brooke Erin, and Emily Hund. 2019. Gendered Visibility on Social Media: Navigating Instagram’s Authenticity Bind. International Journal of Communication 13: 4983–5002. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Alexa K., Mariea Grubbs Hoy, and Alexander E. Carter. 2022. An exploration of first-time dads’ sharenting with social media marketers: Implications for children’s online privacy. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, Aline Shakti, Anja Bechmann, Michael Zimmer, Charles M. Ess, and Association of Internet Researchers. 2020. Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0 Association of Internet Researchers. Available online: https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Genz, Stéphanie. 2015. My Job is Me. Feminist Media Studies 15: 545–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, Tarleton. 2018. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, Barrie. 2013. The quantitative research process. In A Handbook of Media and Communication Research. Edited by Klaus Bruhn Jensen. London: Routledge, pp. 251–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hearn, Alison, and Stephanie Schoenhoff. 2016. From celebrity to influencer. In A Companion to Celebrity. Edited by P. David Marshall and Sean Redmond. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Helmond, Anne. 2015. The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready. Social Media + Society 1: 2056305115603080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, Joke, and Peter Dahlgren. 2006. Cultural studies and citizenship. European Journal of Cultural Studies 9: 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, Andrew. 2022. YouTube Generated $28.8 Billion in Ad Revenue in 2021, Fueling the Creator Economy. Available online: https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/youtube-generated-288-billion-in-ad-revenue-in-2021-fueling-the-creator/618208/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Insider. 2018. Conheça os 25 Maiores Youtubers Portugueses. Available online: https://www.dinheirovivo.pt/lifestyle/conheca-os-25-maiores-youtubers-portugueses-12800305.html (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Jerslev, Anne. 2016. In The Time of the Microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication 10: 5233–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jerslev, Anne, and Mette Mortensen. 2016. What is the self in the celebrity selfie? Celebrification, phatic communication and performativity. Celebrity Studies 7: 249–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerslev, Anne, and Mette Mortensen. 2018. Celebrity in the social media age: Renegotiating the public and the private. In Routledge Handbook of Celebrity Studies. Edited by Anthony Elliott. London: Routledge, pp. 157–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S. Venus, Aziz Muqaddam, and Ehri Ryu. 2019. Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 37: 567–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, Ana. 2020. Celebrity bloggers and vloggers. In The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication. Edited by Karen Ross, Ingrid Bachmann, Valentina Cardo, Sujata Moorti and Cosimo Marco Scarcelli. Hoboken: Wiley. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/9781119429128.iegmc004 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Jorge, Ana, Lidia Marôpo, and Filipa Neto. 2022a. ‘When you realise your dad is Cristiano Ronaldo’: Celebrity sharenting and children’s digital identities. Information, Communication & Society 25: 516–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, Ana, Lidia Marôpo, Aana Margarida Coelho, and Lia Novello. 2022b. Mummy influencers and professional sharenting. European Journal of Cultural Studies 25: 166–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, Susie, Lawrence Ang, and Raymond Welling. 2017. Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebrity Studies 8: 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Barry. 2018. Cultural studies and the politics of celebrity: From powerless elite to celebristardom. In Routledge Handbook of Celebrity Studies. Edited by Anthony Elliott. London: Routledge, pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Patricia. 2010. “Mumpreneurs”: Revealing the Postfeminist Entrepreneur. In Revealing and Concealing Gender: Issues of Visibility in Organizations. Edited by Patricia Lewis and Ruth Simpson. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 124–38. [Google Scholar]

- Luckerson, Victor. 2016. Instagram Is About to Change in a Massive Way. Available online: https://time.com/4260264/instagram-algorithmic-timeline/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Marwick, Alice E. 2015. You May Know Me From YouTube: (Micro)-Celebrity in Social Media. In A Companion to Celebrity. Edited by P. David Marshall and Sean Redmond. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 333–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, Alice, and Danah Boyd. 2011. To See and Be Seen: Celebrity Practice on Twitter. Convergence 17: 139–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, Kimberly A., and Anup Kumar. 2016. Content Analysis. In The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1–10. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc065 (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Porfírio, Francisca, and Ana Jorge. 2022. Sharenting of Portuguese Male and Female Celebrities on Instagram. Journalism and Media 3: 521–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibling, Casey. 2020. “Real Heroes Care”: How Dad Bloggers Are Reconstructing Fatherhood and Masculinities. Men and Masculinities 23: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveirinha, Maria João. 2004. Representadas e representantes: As mulheres e os media. Media & Jornalismo 5: 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. 2022. Most Used Social Media 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Stehling, Miriam, Lucia Vesnic-Alujevic, Ana Jorge, and Lídia Marôpo. 2018. The co-option of audience data and user-generated content: The empowerment and exploitation of audiences through algorithms, produsage and crowdsourcing. In The Future of Audiences: A Foresight Analysis of Interfaces and Engagement. Edited by Ranjana Das and Brita Ytre-Arne. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan, pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Anália, Paula Campos Pinto, Dália Costa, Bernardo Coelho, Diana Maciel, Tânia Reigadinha, and Ellen Theodoro. 2018. Igualdade de Género ao Longo da vida: Portugal no Contexto Europeu. Lisboa: Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijck, José. 2017. In data we trust? The implications of datafication for social monitoring. MATRIZes 11: 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, José, and Thomas Poell. 2013. Understanding Social Media Logic. Media and Communication 1: 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell, and Martijn de Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York: Oxford University Pres. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jorge, A.; Garcez, B.; Janiques de Carvalho, B.; Coelho, A.M. Parenting on Celebrities’ and Influencers’ Social Media: Revamping Traditional Gender Portrayals. Journal. Media 2023, 4, 105-117. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010008

Jorge A, Garcez B, Janiques de Carvalho B, Coelho AM. Parenting on Celebrities’ and Influencers’ Social Media: Revamping Traditional Gender Portrayals. Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(1):105-117. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleJorge, Ana, Bibiana Garcez, Bárbara Janiques de Carvalho, and Ana Margarida Coelho. 2023. "Parenting on Celebrities’ and Influencers’ Social Media: Revamping Traditional Gender Portrayals" Journalism and Media 4, no. 1: 105-117. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010008

APA StyleJorge, A., Garcez, B., Janiques de Carvalho, B., & Coelho, A. M. (2023). Parenting on Celebrities’ and Influencers’ Social Media: Revamping Traditional Gender Portrayals. Journalism and Media, 4(1), 105-117. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010008