Abstract

Negative, tragic, traumatic and suffering representations continue to dominate the discussions and content on social media in the stories and content related to Syrian refugees. The public, while browsing social media, finds that this representation is the dominant one that dominates the image of refugees. Thus, there is a potential risk that the public’s compassion will be negatively affected after repeated exposure to the dominant representation in light of the inability to put an end to that situation. This study discusses the perspectives of Syrian refugees living in Jordan and Turkey on whether they feel such repeated negative and tragic content about their stories and news on social media could affect the empathy of the audience in hosting communities with them, especially since social media is an open-source platform that all people at any time and from any place can post, re-share, comment and create content by adding texts, photos and videos, not like traditional media, which are controlled more than social media platforms for open participatory content. This study aims to explore how a vulnerable population, such as Syrian refugees in Istanbul and Amman, sees the effect of negative representation on themselves and their image in the hosting communities and does not aim to examine or offer any conclusion as to whether the public in Jordan and Turkey have experienced compassion fatigue. This study provides and extracts some useful insights, but proves no hypotheses or conclusive evidence regarding the occurrence of compassion fatigue in the public; thus, the study opens the door for the debate on the role that social media plays as a source of compassion fatigue among citizens towards refugees, mainly when they are repeatedly exposed to such negative stories and content, as well as calls for an in-depth and extensive study on the topic from the point of view of the public and citizens in the hosting countries, after examining, understanding and analyzing the opinions and their dimensions of the sample of refugees in this study.

1. Introduction

One of the characteristics of the Syrian refugee crisis is that it is long ongoing and has no clear end in sight. The spark of the revolution at the beginning of March 2011 in Daraa was ignited by some children influenced by the Arab Spring movements. They wrote slogans and drew graffiti against the regime on the walls of their school. Starting from May 2011 thousands of Syrians crossed borders, fleeing from Syria to neighboring countries.

In the year 2013, the conflict increased the number of refugees in March 2013, reaching a total of 1 million and 2 million in September 2013. The humanitarian situation inside Syria became worse. One million refugees were in Lebanon, and a new refugee camp in Jordan (Azraq camp) was opened in April 2014. By June 2014, the number of Syrian refugees was more than 3 million in countries neighboring Syria, and 100,000 had reached Europe. It was reported by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) that the general range of refugees worldwide in 2014 was over 50 million for the first time since World War II, mostly because of the Syrian crisis, the most significant humanitarian emergency of the century (Sherwood 2014).

In 2015, the influx of Syrian refugees continued; thousands of refugees were arriving daily in Greece, and around 1 million refugees reached Europe (UNHCR 2015). The photo of a 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi, a lifeless toddler, face down, washed up on the beach, shocked the world in September 2015 (Smith 2015).

As a result of these bloody events between Syrian citizens and the security and military bodies and the expansion of military operations in most Syrian cities, hundreds of thousands of people have fled to neighboring countries such as Jordan, Iraq, Turkey and Lebanon to escape the war and save their lives and their children’s lives.

The Syrian refugee crisis has dominated news media coverage since its beginning, with news coverage containing portrayals of refugees as a burden on the hosting countries that deplete their economic and financial resources as a result; those countries need support to meet their needs, which refugees have depleted. The discourse that Syrian refugees are a burden on countries was the topic of many governmental discourses in neighboring countries, which host a large number of Syrian refugees. For example, the debates on refugees’ effects on water governance in Lebanon and Jordan and how the two countries faced the “water crisis” due to the refugees’ arrivals and that Syrian refugees exacerbated water scarcity have been developed and have gained prominence in governmental declarations and national mass media (Hussein et al. 2020). That representation of Syrian refugees has been mentioned repeatedly and continues to be mentioned in both traditional and social media. Such discourse, whether it was published in traditional media or used later by social media outlets, comprising both traumatic images and stories of the suffering in addition to the negative representation in the hosting communities, could contribute to negatively affecting the levels of compassion in the public.

The level of distress an individual felt while viewing such content and images was a predictor of reduced compassion (Thomas et al. 2018). Particularly when audiences have continuous exposure to others’ suffering, they may suffer from a possible involuntary unwillingness to help them. Part of the reason for this is that it becomes a mediated habit when the mind becomes overly accustomed to victims’ images and stories, and it subsequently loses its “shock factor” (Pedwell 2017).

“Compassion fatigue” is considered a psychological condition in which the ability to be compassionate lessens over time due to exposure to traumatic events and trauma victims (Sorenson et al. 2017). For example, in nursing, one of the risk factors for compassion fatigue is increased levels of empathy when entering the profession (Sacco and Gorin 2018). Compassion fatigue has primarily been studied in the healthcare context, where employees are continuously exposed to trauma victims (Kelly et al. 2015). Those who work with people who have experienced domestic violence and sexual assault, such as counselors, lawyers and social workers (Dutton et al. 2017) as well as police officers (Turgoose et al. 2017) are also at risk of developing compassion fatigue. Unfortunately, there has been less research into the development of compassion fatigue among members of the public. The sensationalization of these stories affects people, which reduces the individual’s ability to see those within crises as individuals and more of a conglomerate that can be grouped into the Syrian refugee crisis (Vasterman 2018). Sontag (1977), based on her personal observations, said that exposure to suffering images would lessen the “quality of feeling, including moral outrage”. The diminishing in the quality of feeling could lead to affect compassion. As this topic has been studied extensively by those who work with victims of trauma, but less information is available on the effect of exposure to trauma victims’ stories and images through social media channels, there is a need to study it through repeated exposure to the suffering images in social media. As it is on social media, it is common for an issue to become a hot topic for several hours, then interest in this issue fades as another one comes to the forefront of public consciousness (Vasterman 2018). Social media moves quickly, and those who use it are accustomed to moving from issue to issue as news items are released (Slovic et al. 2017).

Social media has produced a new way of consuming information. Social media’s influence is increasing as users of social media outlets increasingly use them as a news outlet. That contributes to compassion fatigue in two ways. The first is that each new crisis has less of an impact because it is seen as part of a continuance of other crises, and thus the habituation mentioned earlier occurs (Pascasio 2017).

On the contrary, studies have found that if the representation of refugees is positive on social media, it could have a positive effect on compassion and reduce compassion fatigue. Some sites, such as Humans of New York (HONY), which is a popular Facebook page with more than eighteen million followers worldwide, provide alternate portrayals as follows: refugees are skilled, normalized and ideologically American, and they are capable of assimilating into American life (Perreault and Paul 2018). The portrayal of Syrian Americans during their daily lives in the (HONY) series positively affected compassion when the individual refugee was presented differently than refugees are traditionally.

This is in contrast to standard imagery of refugees, which typically presents the refugee in desperation and places them in negative representation (Rettberg and Gajjala 2016).

2. Forming Compassion Fatigue on Social Media

Observation showed a great reaction happened to one of the most iconic photos that reflect the refugees’ suffering, which was the image of the death of the three-year-old Syrian child, Aylan Kurdi, who died along with his mother and brother while they were trying to cross from Bodrum (Muğla) to the Greek island of Kos (Clarke and Shoichet 2015).

The photo of Aylan’s death was widely shared throughout the news and then on social media. Aylan Kurdi’s photo contributed to the perception of refugee problems. The reaction that happened was an outpouring of solidarity with Syrian refugees, which peaked in September 2015 when the image first became available. However, one year later, there was a reduction in commitment to the Syrian refugee crisis as an issue (Thomas et al. 2018). That could be explained by the fact that people were exposed to the image repeatedly and therefore became overly attuned to it. In addition to this, increased levels of compassion are due to an inability to keep compassion levels at an increased level over time (Sorenson et al. 2017).

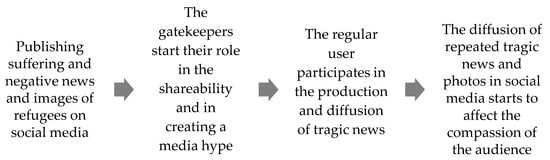

Through social media, the news and images of the tragic contents of the refugees’ stories are published and shared. The gatekeepers or owners of a social media outlet or news account decide whether the information in their newsfeed is worthy to be shared or not (Lewin 1943). That is what makes content like the photo of Aylan Kurdi go viral. The shareability shows that some stories show up or appear on social media more than others appear, which could be attributed to the role of those gatekeepers who contributed to creating media hype. It may be that the reaction to the photos of Aylan Kurdi is a similar process. Some individuals experience an increased level of distress, which causes them to “burn out” and have a reduced level of compassion. That can be referred to as secondary trauma, and it causes the individual to “shut out” further references to that trauma (Sorenson et al. 2016). In this case, individuals who experienced high levels of distress may have had reduced compassion because of the increased reaction upon first viewing the images. That gives insight into compassion fatigue among those who view images of Syrian refugees on social media. Thus, it is not just the Syrian refugee crisis that the public has become accustomed to but also the repeated exposure to “horrific photos” that make these crises less visible (Fehrenbach and Rodogno 2015). Moeller (2002) sees that exposure to negative, violent images leads the audience to lose the ability to feel compassion for victims. She argues that compassion fatigue is not an inevitable consequence of covering the news, but it is an inevitable consequence of the way the news is covered.

Since social media users are dynamic transporters of information, they are involved in sharing and recommending content to their friends and followers. The regular user participates in the production and diffusion of news via social media. The interference of those gatekeepers in the repeated dissemination of tragic news about refugees on social media may lead to fatigue of the audience’s compassion (Vasterman 2018) The media then generates revenue through clicks, which entail sensationalizing stories (Sacco and Gorin 2018). This sensationalization means that the real stories often become lost and have a reduced impact on the public when shared, simply because they do not have shock value (Mast and Hanegreefs 2015). Media bear a great responsibility in highlighting the most important issues in societies. Audience see that online media is much more effective in this regard, and they prefer online media over traditional media when following up on people’s rights issues, as traditional media must follow a winning strategy and do more in this regard (Aldamen 2017). News and media outlets that attempt to reach their audience have to adjust to the rules of those outlets and their aspects of shareability and algorithm. In this case, regular users can create accidental media hype (Roese 2018). Shareability is a significant aspect that means not only do the practical requirements given by social media enable information to spread, but it also means that the user is a dynamic transporter of information shares and recommends content to other friends (Roese 2018). The notion of “media hype” is often related to high news worth. Any emotion can trigger accidental media hype. Thus, there is evidence that compassion peaks shortly after exposure and then reduces as individuals become accustomed to tragic images (Baldacchino and Sammut 2015). There is also the issue of repeated exposure to the crisis news through statuses and sharing of news articles. Over time, it is not easy to retain a high level of compassion.

From the effect of the above-mentioned example of Aylan Kurdi’s photo, it is understood that the media’s influence does not appear directly but after a long period through the accumulation of successive media messages related to one topic.

Figure 1 shows the above-discussed phases of lessening compassion towards refugees after repeated exposure to negative content related to refugees on social media.

Figure 1.

Phases of Forming Compassion Fatigue towards refugees on social media.

Social media makes the news and the content appear to be different from the rest of the media because of the technology trigger that contributes to making the news or content more visible than other content and then makes it reach, in many contexts, the peak of inflated expectations. The gatekeepers’ role is evident in making some contents reach the peak of the audience’s interest and making their empathy grow and positively affect welcoming euphoria, and to some extent, algorithms play a vital role in that. Thus, when news, photos and headlines related to refugees’ suffering and negative representation continue to be circulated and appear repeatedly on social media, the audience could react negatively, as a result, gradually they start to show a less positive reaction since they see or read about the same negative content repeatedly without any ability to make a change, which could affect their compassion towards refugees.

3. Methods

Design and Procedure

Depending on the previously discussed literature review and observation of the study’s problem, this study aims to show how a vulnerable population, such as Syrian refugees, sees coverage of itself, as well as extract some insights about how they see the effect of negative representation on themselves and their image in the hosting communities, and whether this representation, which is characterized by permanent suffering and circulated on social media, in their opinions, affects the empathy and compassion of citizens towards them.

This study is based on exploratory research, which does not offer conclusive evidence. Rather, it aims to gain a better understanding of the problem (Dudovskiy 2016; Saunders et al. 2019). Similarly, the study topic at hand does not intend to provide any conclusive evidence but rather focuses on understanding the perceptions of refugees on the topic and how they see the effects of social media on their lives. Moreover, the findings of this study would provide a new angle by laying a foundation for future research and facilitate the comparison later with the opinions of the audiences or citizens of some hosting countries.

As the aim of this study type is to formulate problems or clarify concepts and form hypotheses rather than test hypotheses (Sue and Ritter 2012), the study depended on understanding the opinions of the refugees through a qualitative approach using focus group discussions to help in identifying the refugees’ opinions and feelings on the studied problem.

The participants in the focus group discussions represented the Syrian refugee population that lives in Jordan and Turkey, and they were a statistically representative sample of the population. The two focus group discussions were conducted in Arabic. A number of 15 Syrian refugees of different ages, education and backgrounds participated in each focus group discussion; the first focus group discussion was held in Amman-Jordan on 20 March 2018, while the second focus group discussion was held in Istanbul on 20 April 2018. Discussions were transcribed and data were organized and coded. The dominant themes were elicited and analyzed, and some were merged into categories according to the thematic analysis.

As refugees are a vulnerable population, special care was taken to assure ethical considerations. Informed consent and voluntary participation were guaranteed, and the participants’ privacy and anonymity were protected. In addition, the confidentiality of the study data is sufficiently protected.

The snowball technique was chosen to encourage participation. Because of the crisis, refugees do not trust participating in activities of which they are unaware. Systematic bombing, arbitrary detention, murder, theft and kidnapping were important factors contributing to a widespread sense of insecurity. The crisis also reduced mutual trust among individuals by 31% due to lack of law and other difficult conditions (Social Watch 2017).

Thus, the snowball technique provided participants with the level of trust in which Facebook groups were members. A snowball technique helped in getting participants to volunteer to ask friends and family members to post a link on their wall. They voluntarily transmitted the link to the questionnaire to other families and friends. This technique helps identify participants that were somewhat difficult to locate and, due to some unusual causes, do not like to be interviewed about their negative war memories. Snowballing is adopted when there are fewer potential participants, and it is expected that these participants will help in finding more or more-relevant participants (Lewis-Beck et al. 2004). Focused and structured discussions gave essential insights into how Syrian refugees see social media’s effect on their lives.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of both focus group discussion participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants in the FGD.

Qualitative data could be analyzed through a thematic analysis approach by describing, analyzing, and interpreting themes in the qualitative data (Clarke and Braun 2017).

The thematic analysis approach was used in this research to determine people’s views, knowledge, experiences, opinions, or values from the analysis of qualitative data. Data coding was one of the thematic analysis steps used hereafter, followed by familiarization, then development and revision of the theme (Guest et al. 2012).

4. Findings of the Qualitative Approach

Extracts from the responses of the participants were coded and analyzed according to the data’s thematic analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The Coding of the Qualitative Data and Its Thematic Analysis.

5. Findings and Discussion

Some participants in the focus group discussions stated that they see their images circulated in many contexts in social media in a contemptuous manner, and they gave an example that mentions exploiting old women waiting to take financial aid while they stand in a queue via that representation of more aid, particularly from international organizations (Extract 1) or to beg sympathy, as some participants explained in (Extract 9), thinking that the image of the refugees is tarnished by showing them in a negative and abused representation, which contributes to negatively affect the empathy towards them in societies.

Some participants see that some media and social media channels show that their existence in hosting countries such as Jordan will destroy the Jordanian economy (Extract 2). The refugees themselves admit and do not deny that they affected the economic situation of the country, but at the same time see that they are not the cause of all reasons for the bad economic situation of the country, as it is conveyed and discussed in social media.

Presenting a negative image of refugees on social media, that they cause economic and social problems in society, and transferring that to many sites as there is no escape from exposure to those negative messages through their presence on more than one site on social media, could lead to the establishment of hatred, which shows the harmful effects of social media. The audience could be passive, and the media messages are more powerful than they are according to the “magic bullet” or “hypodermic needle” theory. The media injects its messages about the repeated the negative stories of refugees straight into a passive audience that is immediately affected by those messages (Lasswell 1927). The audience, in fact, cannot escape from the media messages’ influence and is considered a sitting duck that is very easy to shoot or attack it by the implicit idea, and they cannot do anything for those refugees or change anything in this never-ending suffering. As compassion shown towards needy people fades as the number of people in need of aid increases (Kogut and Ritov 2005). Such a fading of compassion has the potential to significantly hamper individual and collective levels in many aspects, such as political responses to crises, genocide or mass starvation (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Therefore, posting these negative content messages and repeating them affects the public by generating a new reaction towards specific issues and contributing to losing sympathy or even affecting compassion fatigue, which could be one of those reactions of the audience. Social media’s impact is more significant and influential as a magic bullet when the message is transferred and repeated through it, particularly for people who follow many Facebook pages. When news shows that refugees always suffer and are economic burdens in hosting countries, that news is transmitted from one site or outlet to another, as a result, recipients are affected by the content automatically and directly, whatever their defenses were, like a strong, effective intravenous fluid injected into a vein and reaches all sides of the body in a matter of moments. It could not be disassembled because it is a hypodermic needle under the skin, a direct, robust, fast and direct impact on the masses.

However, some participants think that refugees do not receive more sympathy in many cases, but instead, social media users could become bored from reading and browsing the suffering of refugees repeatedly. The feelings of sympathy fall into numbness when the audience feels that they cannot change the current situation by thinking of a normal situation. The repeated news traps readers everywhere, which does not enable the audience to escape from its messages. The accumulation of social media messages with continuous repetition enhances their significant impact and influence, reducing the public’s chances of selecting their perceptions and leads the public to adopt new ideas, and different values vary from one person to another. Repeating the stories of suffering without the ability to do anything for those people makes others lose empathy or even contributes to incitement against them (Extract 10).

A positive emotional response is expected to decrease when the number of needy people increases. Accordingly, compassion fade denotes decreases in positive affect that lead to decreases in donations as the number of people in need increases (Västfjäll et al. 2014). For that reason, we can understand that repeating such representations about refugees and increasing representation by publishing more stories about more refugees could have a negative effect on the reaction to that suffering. As the number of needy people increases, it could be more difficult to empathize and could lead to more negative emotions (Västfjäll et al. 2014).

Some participants think that social media focuses more on stories outside of Syria and gave them more coverage and importance, such as stories of refugees in camps in hosting countries, asylum journeys to Europe by sea, refugees’ problems and the international community’s failure, the difficulties of life in the camps, the crisis of Al-Rukban camp and what happened with the Syrian refugees in the countries of asylum and resort to the Turkish border.

Furthermore, they think that social media focuses on topics such as follows: Grants and monetary assistance to the refugees, the future of youth and migration, rescuing people at sea, refugee issues in Lebanon, the risk of illegal and unregulated migration by sea, poor living conditions for refugees, hate speech, hosting communities’ lack of acceptance of large numbers of refugees, difficulties and dangers faced by refugees, the concentration of refugees and asylum burdens, tragic stories such as drowning, immigration to Europe, family reunification, focus on the negative impact of refugees on hosting countries, lack of work opportunities in neighboring countries, the length of the crisis without a solution, the economic and social situation of refugees, international parties and conferences only talk about the need for Syrians to return to their country and the suffering of the families over the loss of one of their members.

Some participants mentioned some words and expressions that express their feelings when they see or read news related to the Syrian crisis. They were psychological anxiety, anger, loss, homelessness, stress, shortness, suffering, crimes, violations, bombing, killing, arresting and displacing (Extracts 3, 4). The blood and slaughter scenes displayed through social media have had adverse effects on refugees when they see their relatives’ photos that make them feel fear for their family members in Syria. Exaggeration in transferring news via social media also negatively affects the Syrian issue, since some sites are changing stories and lying in line with what exists.

Furthermore, the discussion in Amman revealed that some participants think that social media focused on negative news more than positive news, which contributed to the magnification of the problem and portrayed Syria as a burning place of war (Extract 5). It could be concluded from above that even refugees themselves could be subjected to feeling fatigue and disappointment from the news and represent their stories and situations negatively and miserably, as they mentioned in Extracts 3, 5 and 7.

Some participants see that anyone using social media outlets are not authentic and credible and could be used by some to exaggerate false news and stories about them (Extract 6). Social media does not always convey the news and publish correct information, which contributes to the circulation of false news without verification and the distortion of the refugees’ image, thus causing attacks on the refugees in some situations. Through the discussion, the participants said that they see that the stories of Syrian women and children posted and shared through social media are mainly negative. No one had mentioned success stories or that anything had a positive effect on Syrian women or children who overcame the dire circumstances of their lives. The participants mentioned five Syrian children whose social media focused on their stories, and they were: (1) Aylan Kurdi, who died on the shores of Europe when the boat drowned while his family was going by sea to Europe. (2) Hamza Al-Khatib, a 13-year-old Syrian boy from the town of Giza, was detained during a protest against the Syrian government in Daraa. He was described as the symbol of the revolution. The child, Hamza Al-Khatib, went into a demonstration with the people of his town, calling for the removal of the siege on the people of Daraa. During the demonstration, he was shouted at and killed in the village of Sayda in the city of Daraa on 29 April 2011. He was transferred to Daraa National Hospital and transferred from there to Tishreen Military Hospital. On Tuesday 24th May, Hamza’s body was returned to his family mutilated. His body showed the torture and bullets he was subjected to. He received a bullet in his right arm, another in his left arm, a third in the chest, a broken neck and his genitals were cut. A page in his name was created on “Facebook” exceeded the number of seven thousand in six hours and, in less than twenty-four hours, rose to more than sixteen thousand. Activists on electronic opposition websites were quick to vow to avenge Hamzah, calling for a demonstration on Saturday and zooming on rooftops in the middle of the night (facebook.com/hamza.alshaheed, accessed on 12 November 2022). (3) Omran Daqneesh, a 5-year Syrian boy from Aleppo gained media attention after a videotape of him injured in what was alleged to have been an airstrike appeared on the Internet. (4) Tal Al-Mallouhi, a Syrian blogger from Homs was arrested for publishing some materials on her blog before the crisis. In December 2009, Tal was taken from her home by Syrian forces, which took issue with her blog content. The Syrian government accused her of being a spy for the United States of America (Black 2010). The girl was walking on metal cans due to a lack of prostheses and was being treated by the Turkish Red Crescent (Sengupta 2018). The participants did not remember the name of the girl Maya Al-Mari.

Thus, social media notably contributed to capturing the world’s attention on some photos or news more than others, as all participants knew Hamza Al-Khatib and Omran Daqneesh, while none of them remembered the name Maya. As some participants think that social media outlets used children’s photos for fame, and it harmed them that the stories of the Syrian children were used as a trade on the one hand and for fame on the other hand, such as in the case of the children Omran and Aylan (Extract 8).

The participants’ points of view were that all of what was presented were around the destruction and shelling taking place in Syria. All the stories that they mentioned were tragic and had a negative psychological effect on them, and even the refugees themselves feel bad when they read or face the negative stories and topics repeatedly. That representation affected them at the first level as they had a bad psychological state after that exposure (Extract 7), as a result, the audience from non-refugees is supposed to feel the same level of the negative psychological effect, which leads to compassion fatigue too.

Social media outlets have a role in the order of priorities and concerns of recipients, and here we find that the refugees mentioned specific topics that the media may have focused on and raised more than others raise. According to Max McCombs and Donald Shaw, who developed the agenda-setting theory in a study in 1968, there is a relationship between the media’s issues and the growing public interest in those issues. The media has a significant influence on the audience and what they should think about. Prioritization means shifting prominence and attention and moving issues from the media agenda to the public agenda (McCombs and Shaw 1972).

As a result of media influence on what the audience should think and repetition of some issues more than other issues, which could be topics and issues of suffering and pain of refugees and vulnerable people, which forms compassion fatigue in a vast number of audiences.

Social networks have a role in formulating the public agenda when certain features of new media content, such as hyperlinks and multimedia, highlight issues or specific events. Social networks can build journalists’ agendas and thus the public’s agenda on some issues, especially issues of war and crises. The new media can affect the importance placed on the public agenda’s topics by focusing on some of them repeatedly and ignoring others, or by giving them the same space or focus.

It is noticed when a person does something terrible, but it does not have immense significance for all people. However, when it is framed via the media that he is a Syrian refugee or has been granted citizenship or aid from the hosting country, it could open the door for a more powerful attack against him and attack the government and the state that gave rights to those refugees in return. It means that content in media has no meaning in itself unless it is employed in the context of media outlines that reset texts, words, and meanings and use dominant social understandings and principles (Goffman 1974). Framing a negative image and message in the media opens the door for audiences to lose empathy for them or even have hatred for refugees. Thus, the media uses part of the content to put it in general and vital social formats to identify and enlarge the event and then simplify it to develop a solution.

Here, we see the media message’s ability to be framed and directed through social media to influence opinions and trends. Therefore, it is a process for the communicator when he/she reorganizes the message into people’s perceptions and their influential effects. The media framework is used to make people more aware of social situations. They are thought to affect the awareness and understanding of the news by the audience. As a result, they not only tell the audience what issues to think about but also how to think about those issues (Goffman 1974). The impact of the media frameworks on the message is not only achieved through the deliberate formation of the framework but is also achieved through the deletion and ignoring of omissions intended and perhaps inadvertent, by those who manage the media message (Entman 1989).

The participants in the focus group in Istanbul also consider that social media contributed to disseminating false information about refugees and showing that Syrians live at the expense of Turks and steal jobs from natives. Most people have false ideas about all Syrians because of the representation and adverse effects that have increased problems and sometimes caused hatred.

The discussion revealed that the participants saw the Syrian refugees described as a catastrophe via social media channels. Some users and comment writers claim that refugees have usurped their livelihood and thus hate them. There is also the accusation that Syrian refugees consume the infrastructure in the hosting country. As a result, compassion is affected and hatred is gradually spread, and it appears clearly in provocative comments and immoral responses and throwing accusations against refugees.

Some participants in Istanbul felt that, at the beginning of the revolution, social media was positive, but for specific agendas, hate speech was systematically reinforced, and the public joined this speech as a result of ignorance, which helped to spread hateful hate speech such as using some aggressive Twitter hashtag campaigns to kick Syrians out of Turkey.

The participants in Amman clarified that most criticism comes from the streets, media and social media, saying that the Syrians caused an economic burden when they came to Jordan. Achilli states that the Syrian crisis’ protracted nature has been dramatic; both the Syrian refugees themselves and the hosting communities in Jordan pay a high price. Jordan is under severe tension due to the huge influx of refugees, which has overstretched its infrastructure and threatened its national stability. That has had a significant negative impact on the living conditions of Syrian refugees living in Jordan. The influx of refugees has increased the demand for education opportunities, housing, food, sanitation, energy water, and housing intolerably (Achilli 2015).

Analysis of the discussion revealed that the refugees feel that this negative representation could make the people less compassionate with their issue, as they feel that they are exploited by the media when they focus on them and say that they take funds (Extract 1), presenting them as an economic burden in the hosting countries (Extract 2). There is less humane representation, even with children when they exploit the images of children for fame, such as Aylan Kurdi and Omran Daqneesh, not for the advantages of helping the refugees as they described it as a trade (Extract 8). They see their represented images are not presented compassionately, but contemptuously living dependent on others’ aid and funds (Extract 9). They think that such a repeated representation affected their acceptance in the societies, as some revealed that they are dealt with as thieves who stole jobs and work opportunities from the Turks in Turkey, and their continuous representation focused on the fact that they receive a lot of financial aid without any work or effort, which made a percentage of the society not only reduce its empathy towards them but also adopt hate speech against them and demand their deportation to Syria. This was confirmed by all the participants in Istanbul specifically and supported by the participants in Amman (Extract 10) in that they believe that abusing refugees on social media reduces the chance of empathy. As well as they see that this negatively affects the overall perception of refugees in society and contributes to incitement against all refugees.

6. Conclusions

Presenting a negative image of refugees on social media, that they cause economic and social problems in society and transferring that to many sites ensures that there is no escape from exposure to those negative messages through their presence on more than one outlet or platform on social media could lead to the establishment of harmful effects. As the discussion revealed, the refugees feel that they are exploited by the media when the media represents them as taking funds and being a burden or threat to the country’s economy. The refugees see repeated publishing via social media as a burden or negative representation that affects their image in the hosting countries as well as their acceptance in their hosting countries, making the people less compassionate toward them, creating tension between them and the citizens and contributing to incitement against them.

The study found that even refugees themselves are aware of their repeated negative image in media and circulated in social media and how that repeated representation could be a reason for lessening compassion towards them in the audience.

7. Implications

In this study, compassion fatigue was a term used to describe public reactions towards refugees when they become accustomed to negative content and images and representations of refugees through social media and, as a result, become unable to be more compassionate towards refugees’ stories.

The use of social media to share stories means that we are all exposed to trauma regularly. The repetition of certain negative content could make the audience members who were accustomed to those stories reduce their compassion. That is particularly relevant in the case of stories and images as well, which have become increasingly graphic over time. The public’s habituation toward these graphic images means that people are no longer able to view the victims of these images as individuals but rather as part of the media machine (Mast and Hanegreefs 2015). This habituation becomes part of the population’s psychological fabric, thus reducing the individuals’ ability to feel compassion for those in the images. Because of this prolonged exposure to the ongoing crisis, compassion fatigue begins to set in.

As the discussion revealed, the refugees think that the audience could be distressed when they read and see the same negative stories related to refugees on social media. Such insights into the refugees open the discussion of whether that related representation accumulatively could affect the empathy of the audience and create compassion fatigue later if the audience is distressed when they are exposed to the same negative stories. The repeated negative representation through social media is significant as a magic bullet when the message is transferred and repeated, particularly for people who follow many social media pages. When content shows that refugees always suffer and are economic burdens in hosting countries, recipients are affected by the content automatically and directly, whatever their defenses were, like a strong, effective intravenous fluid injected into a vein and reaching in a matter of moments all sides of the body.

Furthermore, whether the positive response of the individuals who were giving charities to some of the Syrian refugees could be decreased when they continued to see the continuous negative representation of refugees and whether that negative representation could lead to decreases in donations from people after the increase in unacceptance and hatred towards those refugees in some societies after being exposed to a negative representation.

8. Limitations and Future Research

The practical and theoretical framework of this study is based on certain research design limitations. The current study mainly relies on a qualitative approach. However, the insights of refugees of different genders, qualifications, ages, positions and living countries could help in providing hypotheses and guiding future studies using a quantitative approach.

Future research could be conducted to investigate in depth the perspectives of the citizens of the hosting countries and compare the findings with the findings that emerged from this study, thereby allowing investigation of the initial findings of the effect of repeated exposure to negative representation through social media in creating compassion fatigue towards other groups, such as refugees, as well as further research into how compassion fatigue processes develop over time concerning the prolonged, unending Syrian refugee crisis.

9. Recommendations

Based on the insight extracted from the discussion with the refugees, the study calls for an in-depth and extensive study to study the subject from the point of view of citizens in the hosting countries, after examining the opinions of a sample of refugees in this research, understanding them and analyzing their dimensions.

As well as calling for the reporting of the Syrian refugee crisis from a more humanistic perspective, this could also be an important contribution to reducing compassion fatigue, such as in the Humans of New York series. It is also important to ensure that the sharing of news articles involves a call to action on an individual level and by policymakers, which helps to ensure that readers and social media users feel that they can help those in need rather than reading about the crisis as something that cannot be solved.

Moreover, the study finds that social media and traditional media outlets need to display some of the more positive stories from the refugee crisis to ensure that people do not suffer compassion fatigue from exposure to negative and tragic stories. Consequently, avoiding negative representations of refugees in hosting countries could encourage helping and supporting them and reduce the hate speech against them or their lack of acceptance in societies and their feelings of low empathy and sympathy towards them. As well as that, the compassion of the public has not been exhausted or drained towards them.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent and voluntary participation were obtained, and the participants’ privacy and anonymity were protected.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns.

Acknowledgments

The researcher thanks all Syrian refugees who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The researcher declares no conflict of interest. This study is a part of a comprehensive study that was done on the topic of the effects of social media on the Syrian refugees living in Jordan and Turkey, depending on personal expenses of the researcher and without receiving any financial support from any supporting bodies.

References

- Achilli, Luigi. 2015. Brief Policy: Syrian Refugees in Jordan: A Reality Check. Policy Briefs; 2015/02. European University Institute. Fiesole: Migration Policy Centre. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Yasmin. 2017. The Role of Print and Electronic Media in the Defense of Human Rights: A Jordanian Perspective. Jordan Journal of Social Sciences 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, Godfrey, and Carmen Sammut. 2015. The migration crisis: No human is illegal. The Round Table 105: 231–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Ian. 2010. Syria Accuses Teenage Blogger of Spying for a Foreign Power. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/oct/04/syrian-blogger-spy-jail (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Clarke, Rachel, and Catherine E. Shoichet. 2015. CNN Image of 3-Year-Old Who Washed Ashore Underscores Europe’s Refugee Crisis. CNN. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2015/09/02/europe/migration-crisis-boy-washed-ashore-in-turkey/index.html (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Clarke, Victoria, and Virginia Braun. 2017. Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12: 297–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudovskiy, John. 2016. The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: A Step-by-Step Assistance, 1st ed. Pittsburgh: Research Methodology. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Mary Ann, Sherisa Dahlgren, Maria Franco-Rahman, Monica Martinez, Adriana Serrano, and Mihriye Mete. 2017. A holistic healing arts model for counselors, advocates, and lawyers serving trauma survivors: Joyful Heart Foundation Retreat. Traumatology 23: 143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, Robert M. 1989. How the media affect what people think: An information processing approach. The Journal of Politics 51: 347–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrenbach, Heide, and Davide Rodogno. 2015. “A horrific photo of a drowned Syrian child”: Humanitarian photography and NGO media strategies in historical perspective. International Review of the Red Cross 97: 1121–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, Greg, Kathleen M. MacQueen, and Emily E. Namey. 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, Hussam, Alberto Natta, Abed Al Kareem Yehya, and Baha Hamadna. 2020. Syrian refugees, water scarcity, and dynamic policies: How do the new refugee discourses impact water governance debates in Lebanon and Jordan? Water 12: 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47: 263–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Lesly, Jody Runge, and Christina Spencer. 2015. Predictors of compassion fatigue and compassion satis-faction in acute care nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 47: 522–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, Tehila, and Ilana Ritov. 2005. The “identified victim” effect: An identified group, or just a single individual? Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 18: 157–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasswell, Harold D. 1927. Propaganda Technique in the World War. New York: Peter Smith. (First published in 1927. Reprinted, 1938). [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, Kurt. 1943. Forces behind food habits and methods of change. Bulletin of the National Research Council 108: 35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Beck, Michael, Alan E. Bryman, and Tim Futing Liao. 2004. The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mast, Jelle, and Samuel Hanegreefs. 2015. When news media turn to citizen-generated images of war: Transparency and graphicness in the visual coverage of the Syrian conflict. Digital Journalism 3: 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, Maxwell E., and Donald L. Shaw. 1972. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly 36: 176–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, Susan D. 2002. Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pascasio, Luis. 2017. Mediated compassion and the politics of displaced bodies. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences 5: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedwell, Carolyn. 2017. Mediated habits: Images, networked affect and social change. Subjectivity 10: 147–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, Gregory, and Newly Paul. 2018. An image of refugees through the social media lens: A narrative framing analysis of the Humans of New York series ‘Syrian Americans’. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 7: 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rettberg, Jill Walker, and Radhika Gajjala. 2016. ‘Terrorists or cowards: Negative portrayals of male Syrian refugees in social media’. Feminist Media Studies 16: 178–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roese, Vivian. 2018. You won’t believe how co-dependent they are Or: Media hype and the interaction of news media, social media, and the user. In From Media Hype to Twitter Storm. Edited by Peter Vasterman. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 313–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, Vittoria, and Valérie Gorin. 2018. Journalistic practices in the representation of Europe’s 2014–16 migrant and refugee crisis. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 7: 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Mark, Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2019. Research Methods for Business Students. London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, Ahona. 2018. First New Steps for Syrian Girl Who Used Tin Cans for Legs. Available online: https://www.news18.com/news/world/first-new-steps-for-syrian-girl-who-used-tin-cans-for-legs-1804011.html (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Sherwood, Harriet. 2014. Global Refugee Figure Passes 50 m for First Time since Second World War. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/20/global-refugee-figure-passes-50-million-unhcr-report (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Slovic, Paul, Daniel Västfjäll, Arvid Erlandsson, and Robin Gregory. 2017. Iconic photographs and the ebb and flow of empathic response to humanitarian disasters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114: 640–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Helena. 2015. Shocking Images of Drowned Syrian Boy Show Tragic Plight of Refugees. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/shocking-image-of-drowned-syrian-boy-shows-tragic-plight-of-refugees (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Social Watch. 2017. Social Degradation in Syria: How the War Impacts on Social Capital, Social Watch News. Syrian Center for Policy Research. Available online: http://www.socialwatch.org/node/17648 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Stephano, Effi (1973) Performance of Concern Art and Artists 8: 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson, Claire, Beth Bolick, Karen Wright, and Rebekah Hamilton. 2016. Understanding compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A review of current literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 48: 456–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, Claire, Beth Bolick, Karen Wright, and Rebekah Hamilton. 2017. An evolutionary concept analysis of compassion fatigue. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 49: 557–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, Valerie M., and Lois A. Ritter. 2012. Conducting Online Surveys. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Emma F., Nicola Cary, Laura GE Smith, Russell Spears, and Craig McGarty. 2018. The role of social media in shaping solidarity and compassion fade: How the death of a child turned apathy into action but distress took it away. New Media & Society 14: 3778–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgoose, David, Naomi Glover, Chris Barker, and Lucy Maddox. 2017. Empathy, compassion fatigue, and burnout in police officers working with rape victims. Traumatology 23: 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. 2015. Syria Emergency. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/syria-emergency.html (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Vasterman, Peter. 2018. From Media Hype to Twitter Storm. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Västfjäll, Daniel, Paul Slovic, Marcus Mayorga, and Ellen Peters. 2014. Compassion Fade: Affect and Charity Are Greatest for a Single Child in Need. PLoS ONE 9: e100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).