How Mainstream and Alternative Media Shape Online Mobilization: A Comparative Study of News Coverages in Post-Colonial Macau

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Framing Theory and Protest Paradigm

2.2. Mainstream Media’s Bias against Protest

2.3. Shifting Bias through Alternative Media

2.4. Research Question

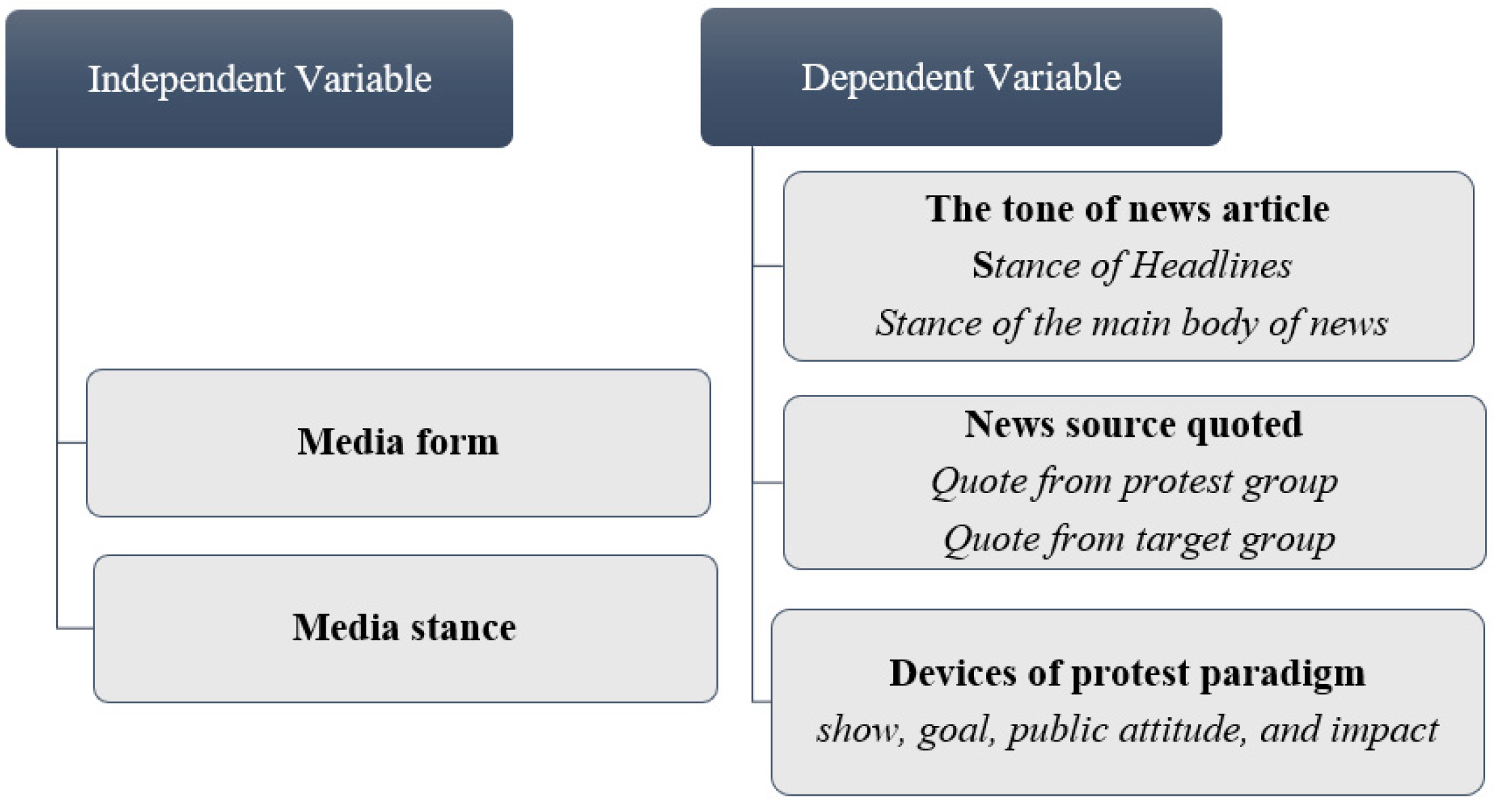

3. Research Method

3.1. Case of Macau’s “Anti-Retirement Package Bill” Event

3.2. Sample Selection

3.3. Measurement

4. Result

4.1. News Attention and Frequency of Coverages

- 1.

- Latent period:

- 2.

- Active period:

- 3.

- Cooling-off period:

4.2. Comparison of Framing Strategies between Mainstream Media and Alternative Media

4.3. Comparison of “Protest Paradigm” Framing Devices in the Protest Coverage

5. Conclusions

- Thematic frames: the news articles are framed thematically; the articles focus on the protest group’s goals and issues rather than their actions;

- Source from protest group: the news articles of protest rely heavily on the protest group as a news source; the coverage tends to cite the protesters or people who have a supportive attitude toward the protest;

- Spectacle: an emphasis on the numbers of protesters and their peaceful actions; the protesters’ brave attitude; the high spirits and the unity of the protest group; and the well-ordered nature of the demonstration;

- Effective goals: emphasize that the protest’s practical goal can bring about substantive changes.

- Public approval: a claim that the public, media, bystanders, or residents support the protest and are concerned about the issues.

- Positive impact: an emphasis on the positive effects of the protest (e.g., the protest can promote economic growth, can improve people’s livelihood, can improve environmental quality, can promote social progress, can change the backward situation in social security, welfare, and service).

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashley, Laura, and Beth Olson. 1998. Constructing reality: Print media’s framing of the women’s movement, 1966 to 1986. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 75: 263–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bagdikian H., Ben. 2014. The New Media Monopoly: A Completely Revised and Updated Edition with Seven New Chapters. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benford, Robert D., and David A. Snow. 2000. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 311: 611–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, Lance W. 2012. The personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 644: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Ron. 2013. The Professional Protester: Emergence of a New News Media Protest Coverage Paradigm in Time Magazine’s 2011 Person of the Year Issue. Journal of Magazine & New Media Research 14: 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Boykoff, Jules. 2006. Framing dissent: Mass-media coverage of the global justice movement. New Political Science 28: 201–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, Michael P., and Mike Schmierbach. 2009. Media use and protest: The role of mainstream and alternative media use in predicting traditional and protest participation. Communication Quarterly 57: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, Michael P., Michael R. McCluskey, Douglas M. McLeod, and Sue E. Stein. 2005. Newspapers and protest: An examination of protest coverage from 1960 to 1999. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 82: 638–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brasted, Monica. 2005. Protest in the media. Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice 17: 383–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caren, Neal, and Sarah Gaby. 2011. Occupy online: Facebook and the spread of Occupy Wall Street. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1943168 (accessed on 22 October 2011).

- Carty, Victory, and Jack Onyett. 2006. Protest, cyberactivism and new social movements: The reemergence of the peace movement post 9/11. Social Movement Studies 5: 229–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu. 2017. The Relationship Between Mainstream Media and Political Activism in the Digital Environment: New Forms for Managing Political Communication. In Media and Metamedia Management. Berlin: Springer, pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Joseph Man, and Chin-Chuan Lee. 1984. The journalistic paradigm on civil protests: A case study of Hong Kong. The News Media in National and International Conflict 23: 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Cissel, Marty. 2012. Media Framing: A comparative content analysis on mainstream and alternative news coverage of Occupy Wall Street. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications 3: 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cottle, Simon. 2008. Reporting demonstrations: The changing media politics of dissent. Media, Culture, and Society 30: 853–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardis, Frank E. 2006. Military Accord, Media Discord a Cross-National Comparison of UK vs US Press Coverage of Iraq War Protest. International Communication Gazette 68: 409–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğu, Burak. 2015. Comparing Online Alternative and Mainstream Media in Turkey: Coverage of the TEKEL Workers Protest against Privatization. International Journal of Communication 9: 630–51. [Google Scholar]

- Downing, John D. H. 2000. Radical Media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert M. 2007. Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power. Journal of Communication 57: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, William A., and Gadi Wolfsfeld. 1993. Movements and media as interacting systems. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 30: 114–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, Herbert. 1979. Deciding What’s News. New York: Patheon. [Google Scholar]

- Gaye, Tuchman. 1978. Making News: A Study in the Construction of Reality. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin, Todd. 1980. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Lebanon: Northeastern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Zhongshi. 2000. Media use habits, audience expectations and media effects in Hong Kong’s first legislative council election. Gazette 62: 133–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Tanni. 2004. Research note: Alternative media, public journalism and the pursuit of democratization. Journalism Studies 5: 115–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcup, Tanni. 2003. The Unspoken-Said’ The Journalism of Alternative Media. Journalism 4: 356–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, Summer, and Thomas J. Johnson. 2011. Overthrowing the protest paradigm? How The New York Times, Global Voices and Twitter covered the Egyptian Revolution. International Journal of Communication 5: 1359–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hartsock, John C. 2000. A History of American Literary Journalism: The Emergence of a Modern Narrative Form. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Bryan C. S. 2011. Political culture, social movements, and governability in Macau. Asian Affairs: An American Review 38: 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Zhaohui. 2012. A Zombie City: A Comparison on the Social Model of Hong Kong and Macau. Hong Kong: Shang Shu Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Husting, Ginna. 1999. When a war is not a war: Abortion, Desert Storm, and representations of protest in American TV news. The Sociological Quarterly 40: 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowitz, Morris. 1975. Professional models in journalism: The gatekeeper and the advocate. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 52: 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, Will, and Clare Saunders. 2014. Protest, Media Agendas and Context: A dynamic analysis. Paper presented at the General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research, Glasgow, UK, September 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kenix, Linda Jean. 2009. Blogs as alternative. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14: 790–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, Stephanie. 2013. Exploring Media Constructions of the Toronto G20 Protests: Images, the Protest Paradigm, and the Impact of Citizen Journalism. Master’s thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Kosicki, Gerald M., and Zhongdang Pan. 2001. Framing as a strategic action in public deliberation. In Framing Public Life. London: Routledge, pp. 51–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, Ying Ho. 2014. Protests against the welfare package for chief executives and principal officials: Macau’s political awakening. China Perspectives 2014: 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Francis L. F. 2005. Collective efficacy, support for democratization, and political participation in Hong Kong. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18: 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Francis L. F. 2014. Triggering the Protest Paradigm: Examining Factors Affecting News Coverage of Protests. International Journal of Communication 8: 2725–46. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, Xia. 2009. A Review and Reflection on the Decade of Macau’s Return to P. R. C. Macau: Ming Liu Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer, Günther, Frank Esser, and Rosa Berganza. 2012. Negativity in political news: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism 13: 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machin, David, and Sarah Niblock. 2014. News Production: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, Thomas Allan, and Iain Mill Hay. 2003. The battle for Seattle: Protest and popular geopolitics in The Australian newspaper. Political Geography 22: 211–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Douglas. 1995. Communicating deviance: The effects of television news coverage of social protest. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 39: 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Douglas, and Benjamin Detenber. 1999. Framing Effects of Television News Coverage of Social Protest. Journal of Communication 49: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Douglas, and James K. Hertog. 1992. The manufacture ofpublic opinion’by reporters: Informal cues for public perceptions of protest groups. Discourse & Society 3: 259–75. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Douglas, and James K. Hertog. 1999. Social control, social change and the mass media’s role in the regulation of protest groups. Mass Media, Social Control, and Social Change: A Macrosocial Perspective 305: 330. [Google Scholar]

- Micó, Josep-Lluís, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2014. Political activism online: Organization and media relations in the case of 15M in Spain. Information, Communication & Society 17: 858–71. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, Kirsty. 2005. Manufacturing Dissent. Single-Issue Protest, the Public and the Press. London: Demos. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, Amit. 1994. International Protection of Journalists: Problem, Practice, and Prospects. Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law 11: 339. [Google Scholar]

- Oliverand, Pamela E., and Gregory M. Maney. 2000. Political Processes and Local Newspaper coverage of protest events: From selection bias to triadic interaction. American Journal of Sociology 106: 463–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Mark Allen. 2003. Anthropology and Mass Communication: Media and Myth in the New Millennium. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Raynauld, Vincent, Mireille Lalancette, and Sofia Tourigny-Koné. 2014. Political Protest 2.0: Social Media and the 2012 Student Strike in the Province of Quebec, Canada. French Politics 14: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, Stephen D., and Pamela J. Shoemaker. 2016. A media sociology for the networked public sphere: The hierarchy of influences model. Mass Communication and Society 19: 389–410. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Charlotte, Kevin M. Carragee, and Cassie Schwerner. 1998. Media, movements, and the quest for social justice. Journal of Applied Communication Research 26: 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, Adam J. 2006. Blogswarms and press norms: News coverage of the Downing Street memo controversy. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 83: 494–510. [Google Scholar]

- Shirky, Clay. 2011. The political power of social media. Foreign Affairs 90: 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, Pamela J. 1984. Media treatment of deviant political groups. Journalism Quarterly 61: 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultziner, Doron, and Aya Shoshan. 2017. A journalists’ protest? Personal identification and journalistic activism in the Israel social justice protest movement. The International Journal of Press/Politics 23: 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford. 2005. Clarifying the relationship between framing and ideology. In Frames of Protest: Social Movements and the Framing Perspective. Edited by Hank Johnston and John A. Noakes. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 205–9. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, David A., Burke Rochford Jr., Steven K. Worden, and Robert D. Benford. 1986. Frame Alignment Process, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation. American Sociological Review 51: 464–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, David A., Sarah A. Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2004. Mapping the Terrain. In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Edited by D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule and H. Kriesi. Malden: Blackweel Publishing Ltd., pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Spellman-Poots, Kathryn, and Martin Webb. 2014. The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest: The Arab Spring and Beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wittebols, James H. 1996. News from the noninstitutional world: US and Canadian television news coverage of social protest. Political Communication 13: 345–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, Ruud. 2015. Reporting demonstrations: On episodic and thematic coverage of protest events in Belgian television news. Political Communication 32: 475–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Kaibin. 2013. Framing Occupy Wall Street: A Content Analysis of The New York Times and USA Today. International Journal of Communication 7: 2412–32. [Google Scholar]

| Protest Paradigm | Score “−1” (Legitimization) | Score “0” (Not Mentioned) | Score “1” (Marginalization) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Show | The news coverage of protests tends to select and put emphasis on the lawlessness and the violent behaviors of the protesters; the news coverage focusses on the dramatic activities of the protest and depicts the protesters’ young age, funny dress, and immature appearance. The coverage usually ignores the goals of the protest. | ||

| Goals | The coverage of protests focusses on the internal dissent of protesters’ goals, the noticeably laughable and radical slogans, or the funny ideas. | ||

| Public attitude | The coverage of the protests emphasizes the public disapproval of the protest. | ||

| Impact | The coverage emphasizes the possible negative impacts of the protest. For instance, the protest may cause the inconvenience to the transportation system, or create disorder in society, and may be inconvenient for the residents living nearby or people working in the neighborhoods. | ||

| Period | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Latent period (11 December 2013–19 May 2014) | 28 | 11.5% |

| Active period (20 May 2014–27 May 2014) | 140 | 57.6% |

| Cooling-off period (28 May 2014–5 July 2015) | 75 | 30.9% |

| Total | 243 * | 100% |

| The Stance of New Article | Mainstream Media (%a) | Alternative Media (%b) | Difference (%a−%b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headline a | The stance of “Headline” (Highly supportive) | 10.0% (N = 14) | 51.5% (N = 53) | −41.5% |

| The stance of “Headline (Highly critical) | 2.1% (N = 3) | 0.0% (N = 0) | 2.1% | |

| Main Body b | The stance of “Main body” (Highly supportive) | 21.4% (N = 30) | 62 (60.2%) | −38.8% |

| The stance of “Main body” (Highly critical) | 3.6% (N = 5) | 0.0% (N = 0) | 3.6% |

| Source | Mainstream Media (%a) | Alternative Media (%b) | Difference (%a−%b) | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of protest group a | 49.3% (N = 69) | 65.7% (N = 69) | −17.7% | 8.549 | 2 | p < 0.01 |

| Use of target group b | 31.4% (N = 44) | 14.6% (N = 15) | 16.9% | 10.693 | 2 | p < 0.01 |

| Media Stance | Show | Goal | Public Attitude | Impact | Tone of Article | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media Stance | 1 | 0.196 ** | 0.506 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.179 ** | 0.556 ** |

| Show | 1 | 0.375 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.418 ** | 0.482 ** | |

| Goal | 1 | 0.521 ** | 0.445 ** | 0.705 ** | ||

| Public attitude | 1 | 0.365 ** | 0.688 ** | |||

| Impact | 1 | 0.528 ** | ||||

| Tone of article | 1 |

| Media | Alternative Media (a) * | Prodemocracy Media (b) * | Neutral Media (c) * | Conservative Media (d) * | χ2 | df | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Paradigm “Show” | 26.94 | 6 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Spectacle scene | 52 | 50.5% | 44 | 67.69% | 6 | 54.55% | 21 | 32.8% | |||

| Freak show | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 7.80% | |||

| Paradigm “Goal” | 65.66 | 6 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Effective goals | 89 | 86.4% | 41 | 63.08% | 6 | 54.55% | 18 | 28.10% | |||

| Ineffective goals | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.54% | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 12.50% | |||

| Paradigm “Public attitude” | 47.42 | 6 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Approval | 87 | 84.5% | 45 | 69.23% | 7 | 63.64% | 21 | 32.80% | |||

| Disapproval | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 4.70% | |||

| Paradigm “Impact” | 76.85 | 6 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Positive impact | 23 | 22.3% | 44 | 67.69% | 6 | 54.55% | 12 | 18.80% | |||

| Negative impact | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 4.62% | 0 | 0.0% | 14 | 21.90% | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, M. How Mainstream and Alternative Media Shape Online Mobilization: A Comparative Study of News Coverages in Post-Colonial Macau. Journal. Media 2022, 3, 453-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030032

Xu M. How Mainstream and Alternative Media Shape Online Mobilization: A Comparative Study of News Coverages in Post-Colonial Macau. Journalism and Media. 2022; 3(3):453-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030032

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Min. 2022. "How Mainstream and Alternative Media Shape Online Mobilization: A Comparative Study of News Coverages in Post-Colonial Macau" Journalism and Media 3, no. 3: 453-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030032

APA StyleXu, M. (2022). How Mainstream and Alternative Media Shape Online Mobilization: A Comparative Study of News Coverages in Post-Colonial Macau. Journalism and Media, 3(3), 453-470. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030032