The Effects of the COVID-19 “Infodemic” on Journalistic Content and News Feed in Online and Offline Communication Spaces

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Neologism “Infodemic” as Point of Departure

1.2. Media and Public Health Crises

- The virus is a biological weapon, developed in a lab.

- The vaccine exists and this pandemic is a “game” of the pharmaceutical companies.

- There are alternative therapies that can treat it effectively.

- 5G technologies are linked to the virus (Imhoff and Lamberty 2020, p. 1113).

1.3. The Coronavirus Pandemic in the Greek Media Ecosystem

2. Structure of the Research: The Combination of Two Data Sets

2.1. The Mass Media Data Set

2.1.1. Period of Study

2.1.2. Sample

2.1.3. Unit of Analysis and Coding

- The type of the news item (article, interview, op-ed, etc.) (related to H2);

- The presence of images (related to H2);

- Whether they are signed by an author or the editorial team (related to H2);

- The sources from which the information mentioned in the text comes, e.g., experts, global organizations (e.g., WHO), people who got sick (related to H3);

- Whether it focuses on human drama or data (related to H2);

- It contains hoaxes and conspiracy theories, e.g., the virus was developed in the lab, etc. (related to H4);

- The type of content (related to H2);

- The main source of reference (related to H2 and H3);

- The presence of a link (coding only applies to sites) (related to H2 and H3);

- The main theme (related to H1).

2.2. The Social Media Data Set

3. Findings

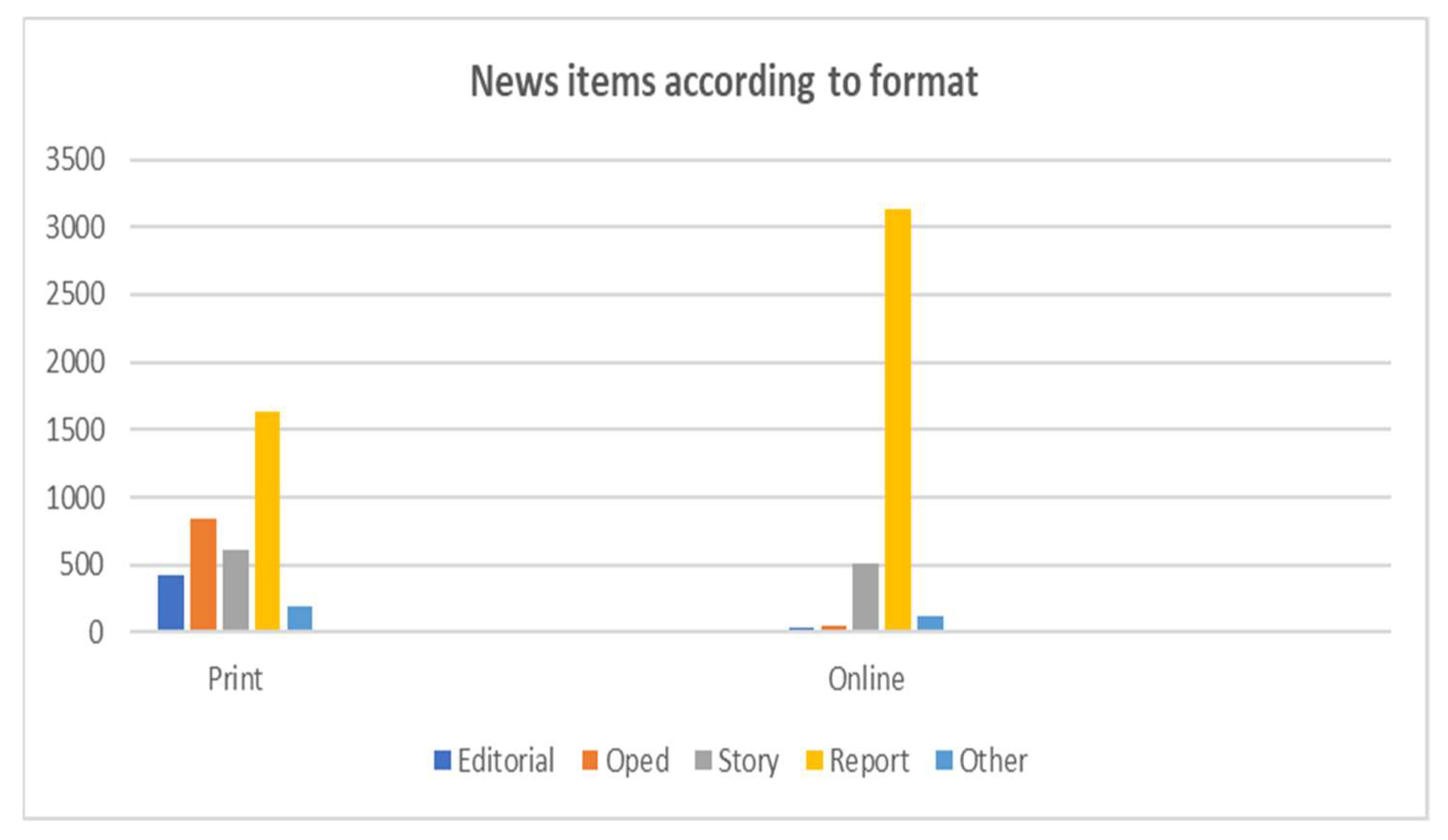

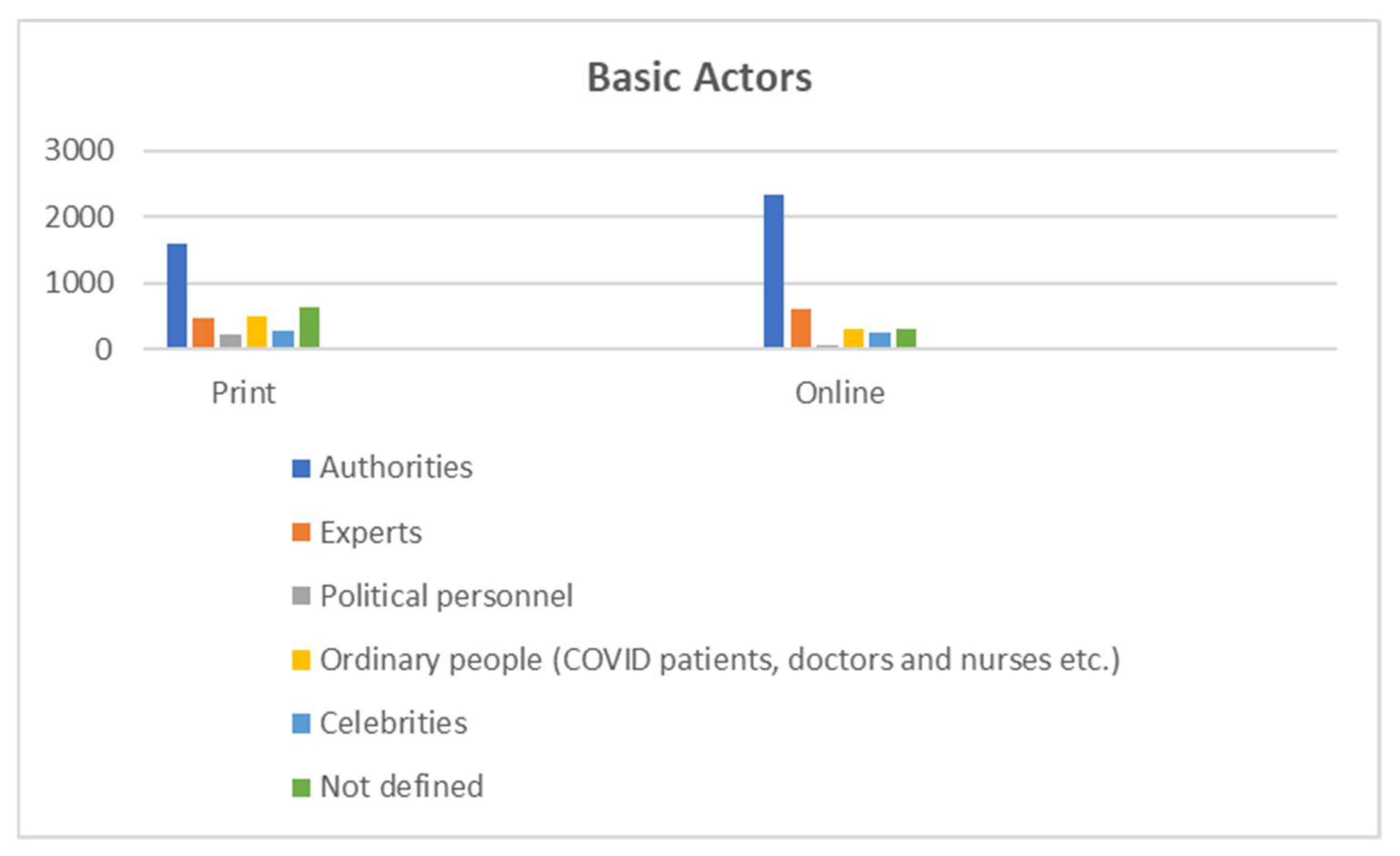

3.1. Media Content

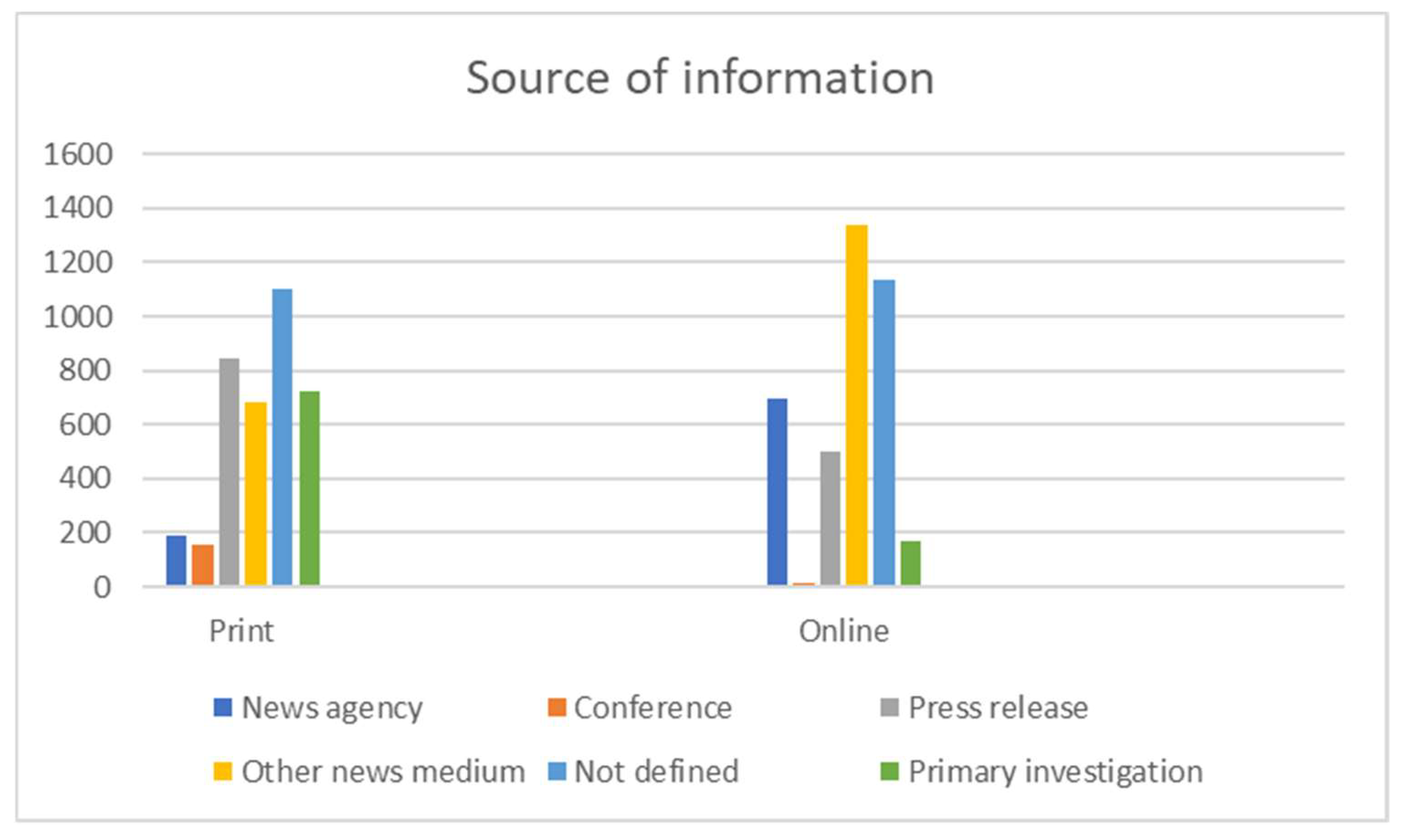

3.2. Source of Information and Use of Hyperlinks

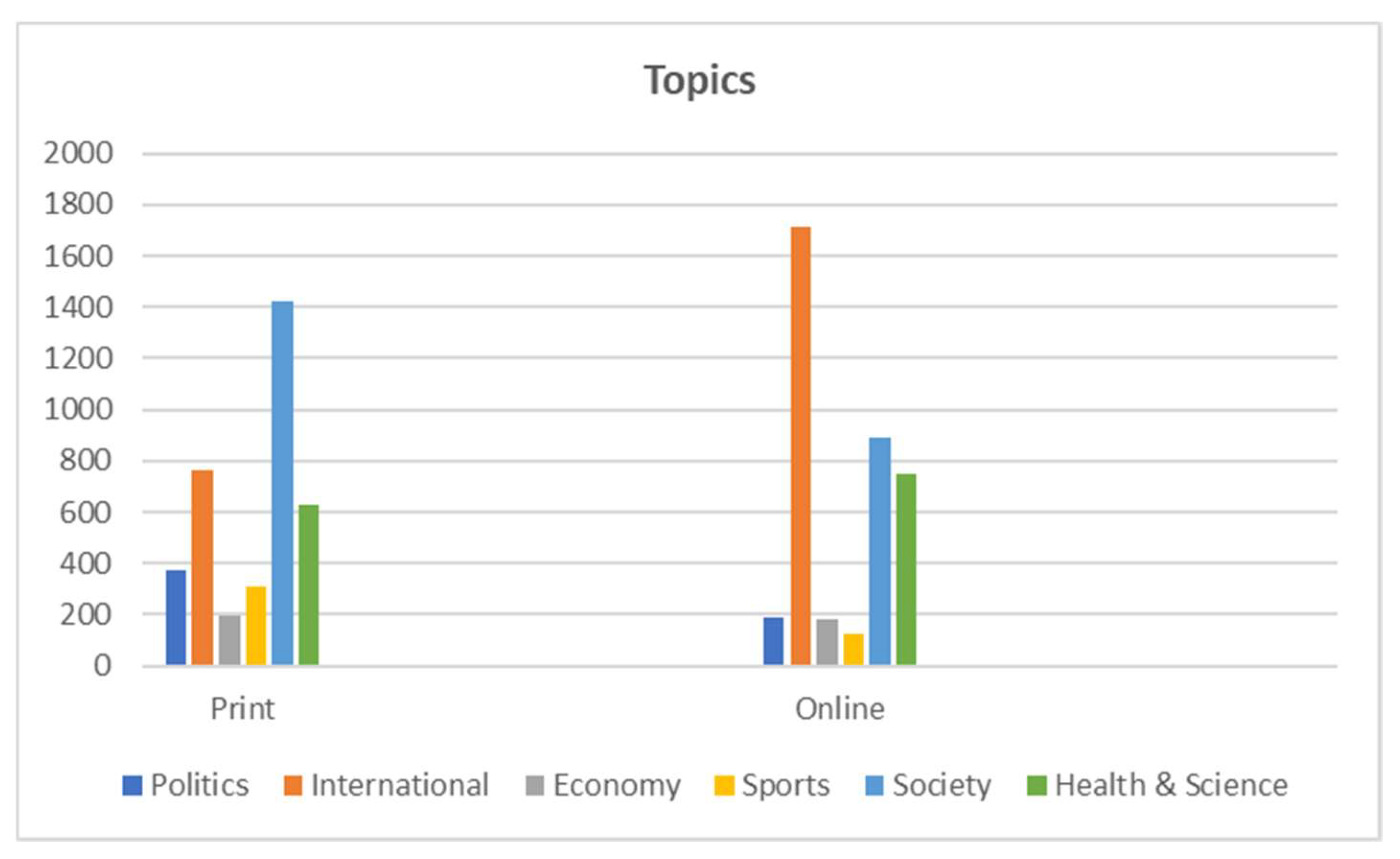

3.3. Topics

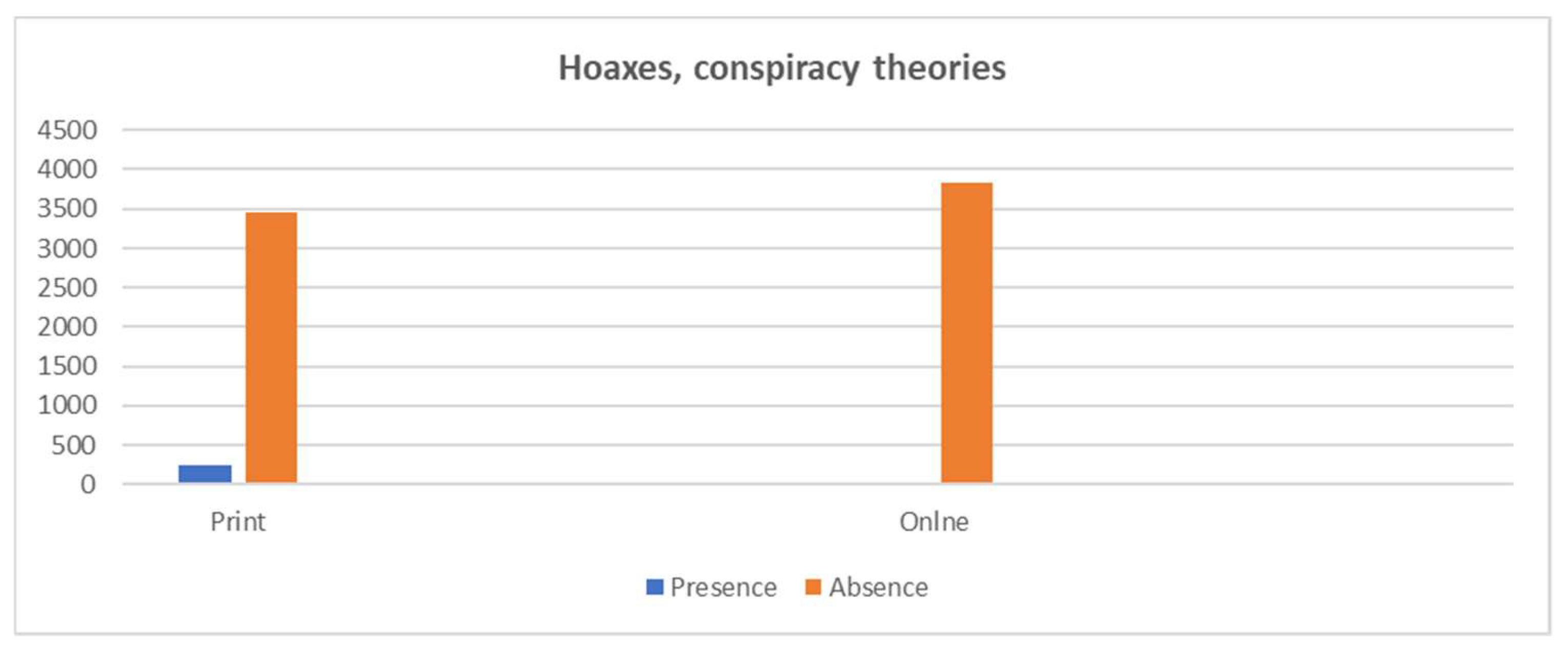

3.4. Hoaxes and Conspiracy Theories

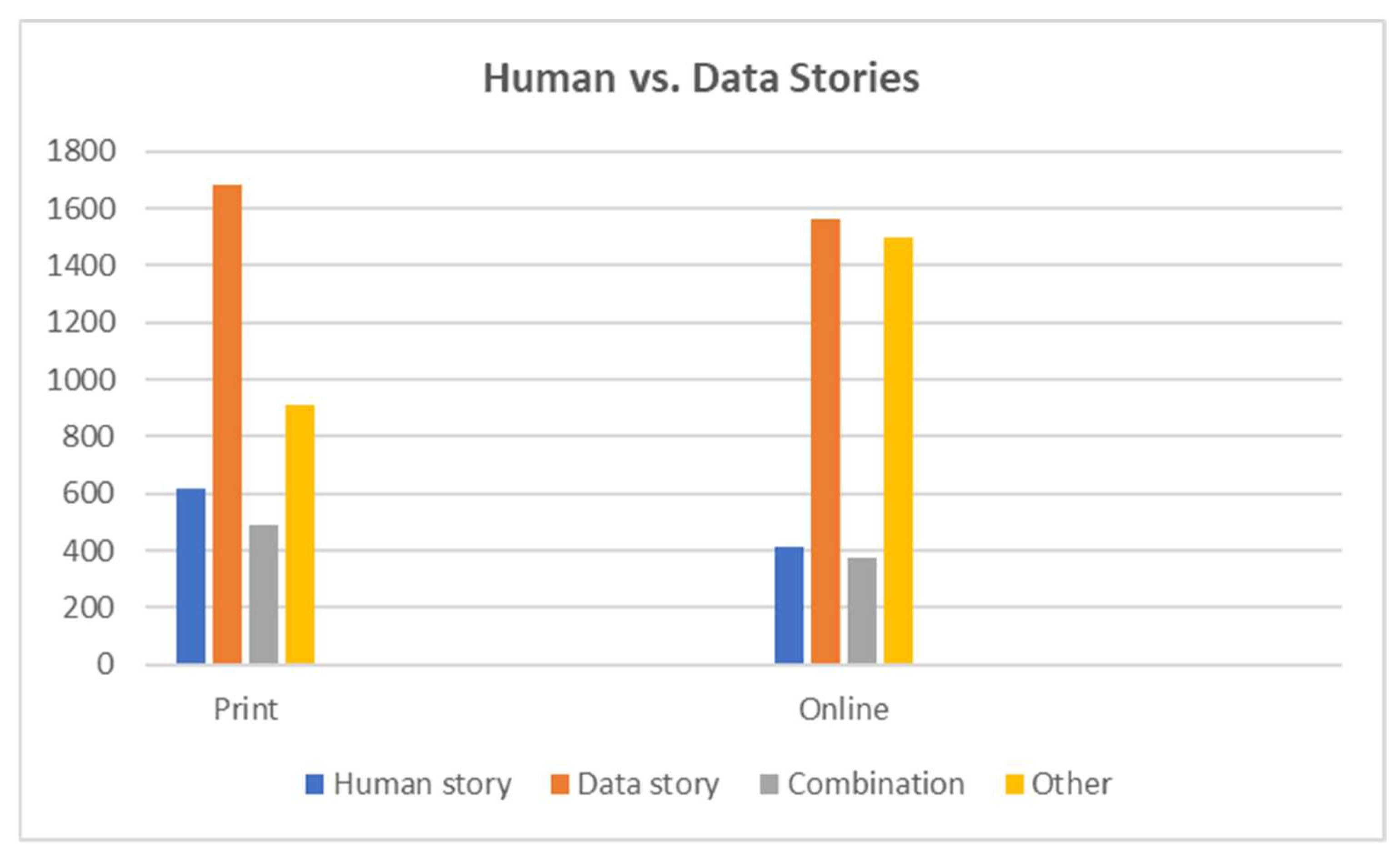

3.5. Human or Data Stories?

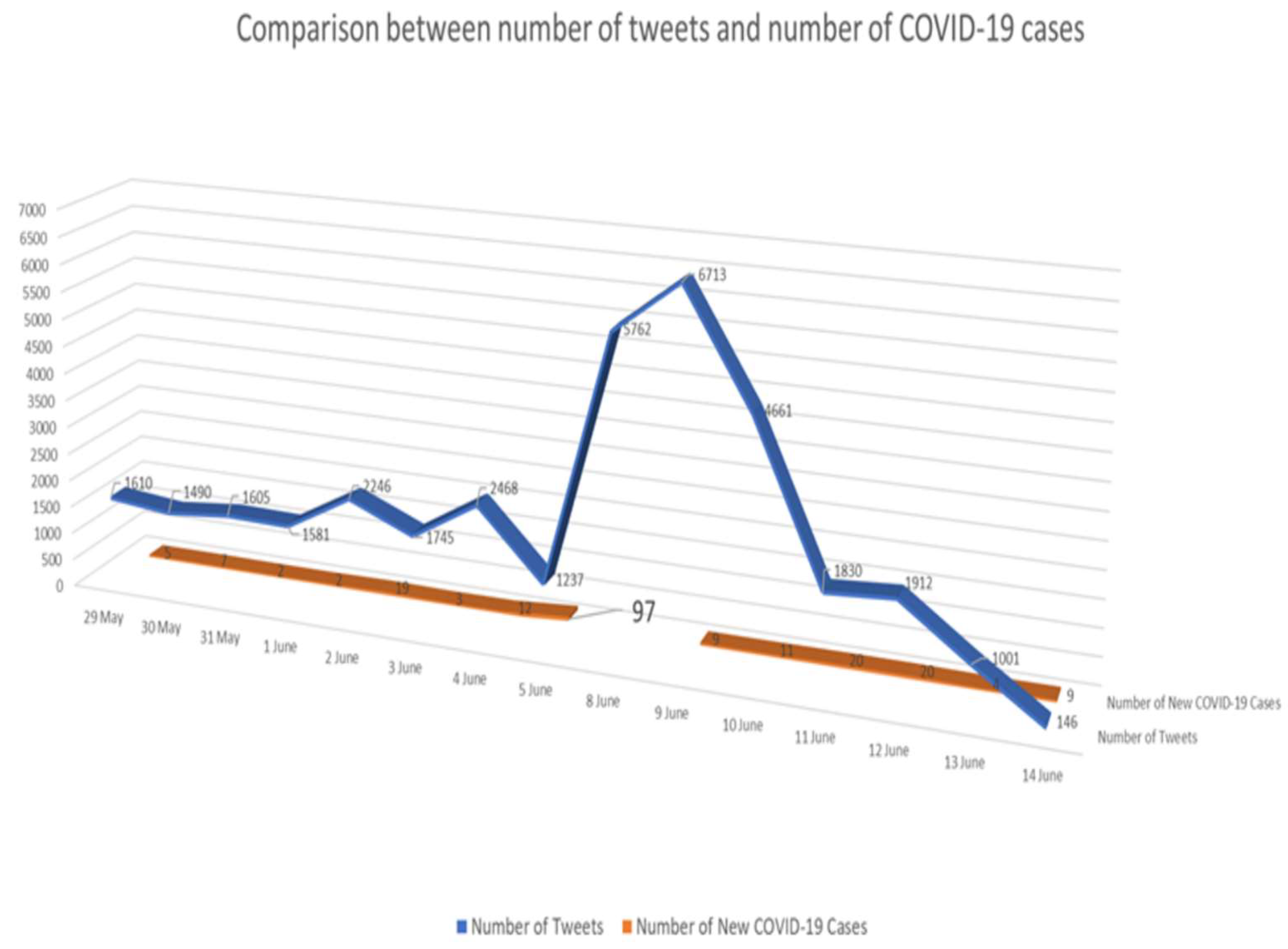

4. Discussion on the Content of Conversation on Twitter

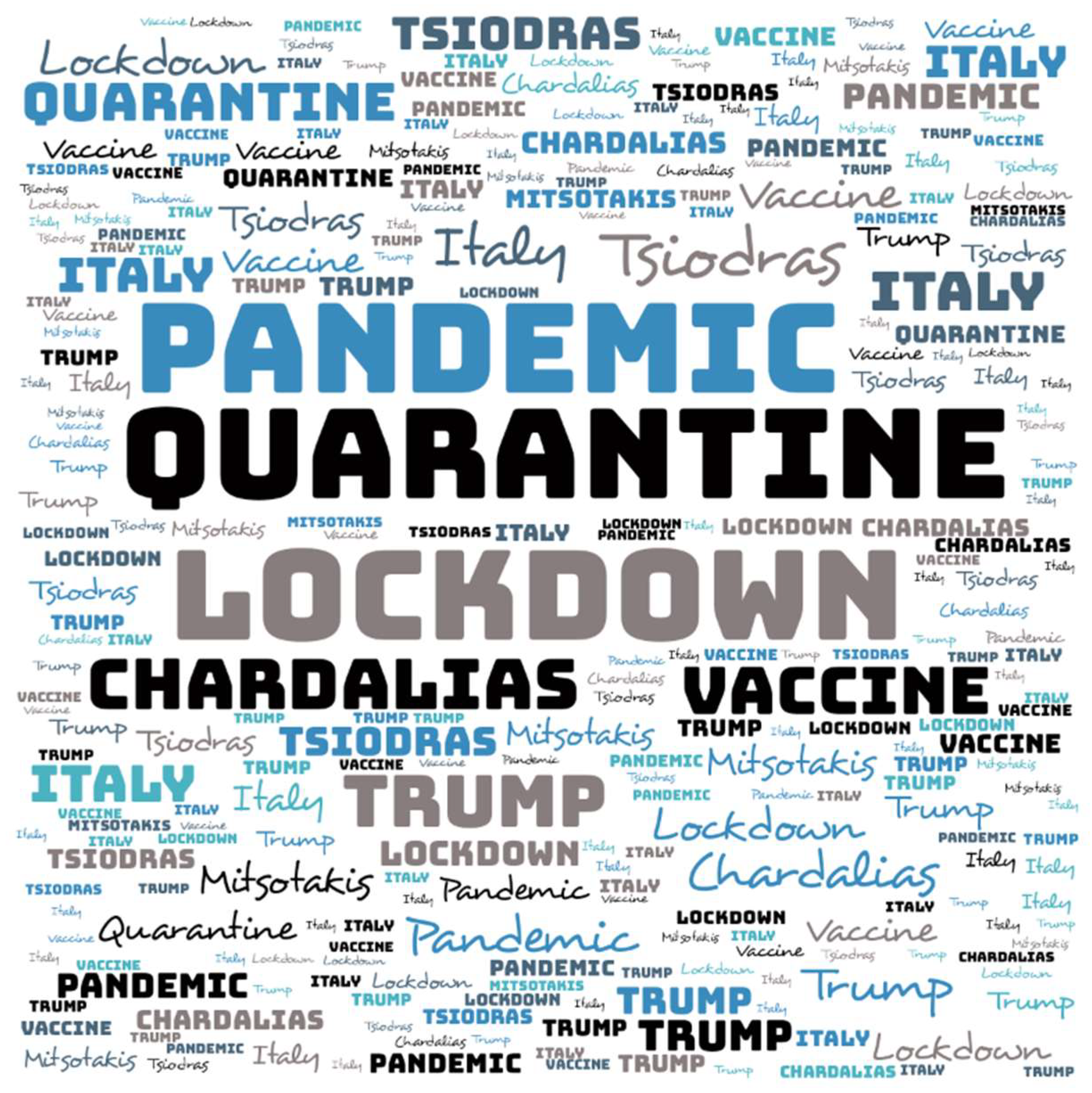

Main Topics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bernadas, Jan Michael Alexandre C., and Karol Ilagan. 2020. Journalism, public health, and COVID-19: Some preliminary insights from the Philippines. Media International Australia 177: 132–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boberg, Svenja, Thorsten Quandt, Tim Schatto-Eckrodt, and Lena Frischlich. 2020. Pandemic Populism: Facebook Pages of Alternative News Media and the Corona Crisis—A Computational Content Analysis. arXiv arXiv:2004.02566. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, Tammy. 2006. Journalism and expertise. Journalism Studies 7: 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, Scott, Felix M. Simon, Philip N. Howard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. Types, Sources, and Claims of COVID-19 Misinformation. Factsheet April 2020: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. Available online: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:178db677-fa8b-491d-beda-4bacdc9d7069 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Carlson, Matt. 2017. Journalistic Authority: Legitimating News in the Digital Era. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, Matteo, Walter Quattrociocchi, Alessandro Galeazzi, Carlo Michele Valensise, Emanuele Brugnoli, Ana Lucia Schmidt, Paola Zola, Fabiana Zollo, and Antonio Scala. 2020. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. arXiv arXiv:2003.05004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalrymple, Kajsa E., Rachel Young, and Melissa Tully. 2016. “Facts, not fear” negotiating uncertainty on social media during the 2014 Ebola crisis. Science Communication 38: 442–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Nick. 2008. Flat Earth News. London: Chatto & Windus. [Google Scholar]

- Depoux, Anneliese, Sam Martin, Emilie Karafillakis, Raman Preet, Annelies Wilder-Smith, and Heidi Larson. 2020. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Travel Medicine 27: taaa0311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, Rino, and Alessandro Sapienza. 2020. How COVID-19 Changed the Information Needs of Italian Citizens. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2006. Political communication in media society: Does democracy still enjoy an epistemic dimension? The impact of normative theory on empirical research. Communication Theory 16: 411–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hekkilla, Heikki. 2020. Finland: Coronavirus and the Media. European Journalism Observatory. Available online: https://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/finland-coronavirus-and-the-media (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Hellmueller, Lea, Tim P. Vos, and Mark A. Poepsel. 2013. Shifting journalistic capital? Transparency and objectivity in the twenty-first century. Journalism Studies 14: 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, Alfred, and Claudia Mellado. 2020. Dimensions of Social Media Logics: Mapping Forms of Journalistic Norms and Practices on Twitter and Instagram. Digital Journalism 8: 864–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, Amanda. 2020. Celebrity Culture Is Burning. New York Times. March 30. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/arts/virus-celebrities.html (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Holland, Kate, Melissa Sweet, R. Warwick Blood, and Andrea Fogarty. 2014. A legacy of the swine flu global pandemic: Journalists, expert sources, and conflicts of interest. Journalism 15: 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, Roland, and Pia Lamberty. 2020. A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Social Psychological and Personality Science 11: 1110–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md Saiful, Tonmoy Sarkar, Sazzad Hossain Khan, Abu-Hena Mostofa Kamal, S. M. Murshid Hasan, Alamgir Kabir, Dalia Yeasmin, Mohammad Ariful Islam, Kamal Ibne Amin Chowdhury, Kazi Selim Anwar, and et al. 2020. COVID-19-Related Infodemic and Its Impact on Public Health: A Global Social Media Analysis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103: 1621–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, Jane, and Susan Forde. 2017. Churnalism: Revised and revisited. Digital Journalism 5: 943–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagashe, Ireneus, Zhijun Yan, and Imran Suheryani. 2017. Enhancing seasonal influenza surveillance: Topic analysis of widely used medicinal drugs using Twitter data. Journal of Medical Internet Research 19: e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotisova, Johana. 2020. When the crisis comes home: Emotions, professionalism, and reporting on 22 March in Belgian journalists’ narratives. Journalism 21: 1710–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnatray, Pradeep, and Rahul Gadekar. 2014. Construction of death in H1N1 news in The Times of India. Journalism 15: 731–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecheler, Sophie, and Sanne Kruikemeier. 2016. Re-evaluating journalistic routines in a digital age: A review of research on the use of online sources. New Media & Society 18: 156–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Terence, and John Bottomley. 2010. Pending crises: Crisis journalism and SARS in Australia. Asia Pacific Media Educator 20: 269. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Seth C. 2020. The objects and objectives of journalism research during the coronavirus pandemic and beyond. Digital Journalism 8: 681–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Joanne Chen. 2012. How young Chinese depend on the media during public health crises? A comparative perspective. Public Relations Review 38: 99–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, Claudia, Daniel Hallin, Luis Cárcamo, Rodrigo Alfaro, Daniel Jackson, María Luisa Humanes, Mireya Már-quez-Ramírez, Jacques Mick, Cornelia Mothes, Christi I-Hsuan Lin, and et al. 2021. Sourcing Pandemic News: A Cross-National Computational Analysis of Mainstream Media Coverage of COVID-19 on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Digital Journalism 9: 1261–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, John E. 1970. Presidential popularity from Truman to Johnson. American Political Science Review 64: 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sastre, Daniel, Luis Rodrigo-Martín, and Isabel Rodrigo-Martín. 2021. The Role of Twitter in the WHO’s Fight against the Infodemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 11990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban, and Max Roser. 2020. Loneliness and Social Media. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/socialconnectionsandloneliness?fbclid=IwAR1cSfXgU7xloKOx0ITWXwSjSmYAl5OFQ9uWNfEs6d9EFtL7WirQGZhww (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Page, Benjamin I., Robert Y. Shapiro, and Glenn R. Dempsey. 1987. What moves public opinion? The American Political Science Review 81: 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos. 2013. Greece: Press Subsidies in Turmoil. In State Aid for Newspapers. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 237–51. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos. 2020. The Greek Media at the Intersection of the Financial Crisis and the Digital Disruption. In The Emerald Handbook of Digital Media in Greece. Bentley: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleios, Georgios. 2013. Media in front of crisis adopting the logic of elites. In Crisis and the Media. Edited by George Pleios. Athens: Papazisis, pp. 87–134. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Quandt, Thorsten. 2008. News on the World Wide Web? A comparative content analysis of online news in Europe and the United States. Journalism Studies 9: 717–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Barbara, Sarah Hartley, Brigitte Nerlich, and Rusi Jaspal. 2018. Media coverage of the Zika crisis in Brazil: The construction of a ‘war’ frame that masked social and gender inequalities. Social Science & Medicine 200: 137–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rothkopf, David. 2003. When the Buzz Bites Back. The Washington Post. May 11. Available online: www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2003/05/11/when-the-buzz-bites-back/bc8cd84f-cab6-4648-bf58-0277261af6cd/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Saltzis, Kostas. 2012. Breaking news online: How news stories are updated and maintained around-the-clock. Journalism Practice 6: 702–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridou, Theodora, Lia-Paschalia Spyridou, and Andreas Veglis. 2017. Churnalism on the rise? Assessing convergence effects on editorial practices. Digital Journalism 5: 1006–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudson, Michael. 2003. The Sociology of News. New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Tsung-Jen, Dominique Brossard, and Rosalyna Wijaya. 2011. News coverage of public health issues: The role of news sources and the processes of news construction. Public Health Yearbook 2011: 93. [Google Scholar]

- Siapera, Eugenia, Lambrini Papadopoulou, and Fragiskos Archontakis. 2015. Post-crisis journalism: Critique and renewal in Greek journalism. Journalism Studies 16: 449–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Lisa, Shweta Bansal, Leticia Bode, Ceren Budak, Guangqing Chi, Kornraphop Kawintiranon, Colton Padden, Rebecca Vanarsdall, Emily Vraga, and Yanchen Wang. 2020. A first look at COVID-19 information and misinformation sharing on Twitter. arXiv arXiv:2003.13907. [Google Scholar]

- Skamnakis, Antonis. 2018. Accelerating a freefall? The impact of the post-2008 economic crisis on Greek media and journalism. Journal of Greek Media & Culture 4: 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Zixue, and Tao Sun. 2007. Media dependencies in a changing media environment: The case of the 2003 SARS epidemic in China. New Media & Society 9: 987–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Touri, Maria, and Ioanna Kostarella. 2017. News blogs versus mainstream media: Measuring the gap through a frame analysis of Greek blogs. Journalism 18: 1206–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiodras, Sotirios. 2020. Press Conference 7 April 2020. Available online: https://www.skai.gr/tsiodras-epipedothike-i-kampyli-ton-nekron-an-proseksoume-de-tha-kanei-apotomi-koryfosi (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Vijaykumar, Santosh, Glen Nowak, Itai Himelboim, and Yan Jin. 2018. Virtual Zika transmission after the first US case: Who said what and how it spread on Twitter. American Journal of Infection Control 46: 549–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, Hong Tien, Le Thanh Trieu, and Hoa Thanh Nguyen. 2020. Routinizing Facebook: How Journalists’ Role Conceptions Influence their Social Media Use for Professional Purposes in a Socialist-Communist Country. Digital Journalism 8: 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Matthias, Gwendolin Gurr, and Miriam Siemon. 2019. Voices in health communication-experts and ex-pert-roles in the German news coverage of multi resistant pathogens. Journal of Science Communication 18: A03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbord, Silvio. 2002. Journalism, risk and patriotism. Journalism after September 11: 201–19. [Google Scholar]

- Waisbord, Silvio. 2018. Truth is what happens to news: On journalism, fake news, and post-truth. Journalism Studies 19: 1866–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | News Site |

|---|---|

| 5th place | In.gr |

| 6th place | Lifo.gr |

| 8th place | Enimerotiko.gr |

| 10th place | Zougla.gr |

| 18th place | Protothema.gr |

| 29th place | Iefimerida.gr |

| 37th place | Newsbomb.gr |

| Newspaper | Circulation Numbers |

|---|---|

| Ta Nea | 11.980 |

| I Efimerida twn Syntaktwn | 5.580 |

| Eleftheros Typos | 3.760 |

| Eleftheri Wra | 2.670 |

| Kathimerini | No data available |

| Makelio | No data available |

| Hashtag | Tracked Since |

|---|---|

| #COVID19 greece | 29 May 2020 |

| #μενουμε_ασφαλεις (stay safe) | 29 May 2020 |

| #κορονοιος (coronavirus) | 29 May 2020 |

| #πανδημια (pandemic) | 29 May 2020 |

| #COVID_19 | 29 May 2020 |

| #καραντίνα (quarantine) | 29 May 2020 |

| #μμε_ξεφτίλες (media are a disgrace) | 29 May 2020 |

| #Τσιοδρας (Tsiodras: the name of the person in charge of Greece’s management of the coronavirus pandemic) | 29 May 2020 |

| Word | Volume |

|---|---|

| Quarantine | 14,963 |

| Pandemic | 7206 |

| Mitsotakis | 272 |

| Lockdown | 245 |

| Italy | 186 |

| Vaccine | 139 |

| Theodoridou | 105 |

| Tsiodras | 110 |

| Chardalias | 90 |

| China | 66 |

| Trump | 65 |

| Account (Screen Name) | Number of Retweets |

|---|---|

| @MDenaxa (journalist) | 527 |

| @paganiotis (unknown id) | 423 |

| @serkot65 (Serafeim Kotrotsos, journalist) | 301 |

| @PithikosTapas (unknown id) | 242 |

| @Kinima_Ypervasi (self-identified as public movement) | 208 |

| @ManosVoularinos (comedian) | 219 |

| @Teletai_Mpouk (funeral services) | 207 |

| @Angelakard (unknown id) | 145 |

| @Kanekos69 (unknown id) | 132 |

| @GltLucia (unknown id) | 122 |

| @bkex (Voula Kexagia) journalist) | 122 |

| Media Account | Number of Retweets |

|---|---|

| amna_news (Athens News Agency) | 115 |

| Iefimerida | 89 |

| Protothema.gr | 57 |

| Makeleio.gr | 55 |

| Ethnosgr | 24 |

| Kathimerini_gr | 22 |

| zougla_online | 20 |

| In.gr | 10 |

| Newsbomb | 9 |

| ta_nea | 6 |

| Account (Screen Name) | Tweet | Number of Retweets |

|---|---|---|

| @a_olimpia | If we go for a second lockdown, instead of a bathing suit we will need a gaberdine | 45 |

| @variemaikpeinaw | Sweet boys and girls put your masks on until I come so the second lockdown finds me in Greece | 22 |

| Account (Screen Name) | Tweet | Number of Retweets |

|---|---|---|

| @paganiotis | The student who broke the quarantine and held a party is wanted | 94 |

| @PithikosTapas | Wanted, wanted (after the song of her famous mother) | 101 |

| @ManosVoularinos | I think we all know that someone who returns from the UK and breaks the quarantine should pay a fine | 10 |

| @gesta_res | The daughter of a well known family in Thessaloniki returns from the UK where she studies and doesn’t follow the quarantine as obliged | 3 |

| @IsidorosLos | Yes, mate. The daughter of Theodoridou and businessman Mpetas came back from London and didn’t stay in quarantine for 14 days | 9 |

| @Sampsonius_ | The girl returned via Bulgaria. She was so happy that broke the quarantine | 18 |

| Account (Screen Name) | Tweet | Number of Retweets |

|---|---|---|

| @tetRadio | Efimerida twn Syntaktwn (daily newspaper) received 39 thousand euros for the campaign # stay safe | 64 |

| @el_ges | The most anti-educational bill, concerning the future of our children, was passed by #New Democracy kseftiles (a word used to show disgrace) and at the same time money were given to non-existent media. | 6 |

| @ofp8791 | @SteliosPetsas (government spokesman) said that #Documento didn’t get advertising money because it says that #COVID19greece is a lie. What a punk! | 4 |

| @_plystra | I live in a country that frees pedophiles, closes hospitals that treat children but advertises the campaign #stay safe | 22 |

| @aigeas | The 20 million “for our protection” from the coronavirus were distribute to “ghost” companies and to the pockets “of our favorites”. | 10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kostarella, I.; Kotsakis, R. The Effects of the COVID-19 “Infodemic” on Journalistic Content and News Feed in Online and Offline Communication Spaces. Journal. Media 2022, 3, 471-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030033

Kostarella I, Kotsakis R. The Effects of the COVID-19 “Infodemic” on Journalistic Content and News Feed in Online and Offline Communication Spaces. Journalism and Media. 2022; 3(3):471-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostarella, Ioanna, and Rigas Kotsakis. 2022. "The Effects of the COVID-19 “Infodemic” on Journalistic Content and News Feed in Online and Offline Communication Spaces" Journalism and Media 3, no. 3: 471-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030033

APA StyleKostarella, I., & Kotsakis, R. (2022). The Effects of the COVID-19 “Infodemic” on Journalistic Content and News Feed in Online and Offline Communication Spaces. Journalism and Media, 3(3), 471-490. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3030033