Abstract

This study investigates and reflects upon the interpretations of (narco) folk saints on the Texas–Mexico border by analyzing their recent representations in local Texan and national U.S. print media. These articles portray the melding of religion and crime to promote anti-immigration ideas and politics in Texas. To understand the connection between culture and crime on the Texas–Mexico border, this essay first delves into each aspect individually, providing their origins and historical context. An analysis of U.S. and Mexican statistics illustrates that many of the societal issues spurring the creation and devotion of folk saints remain prevalent in borderland culture today, including governmental shortcomings, dissatisfaction with the Church, social conditions, and media prejudice. The ubiquity of these themes in borderland daily life continuously incites more (narco) folk saint devotees, and Texas print media further distort the relationship among religion, culture, and crime until they eventually become inseparably intertwined in popular public opinion.

Keywords:

folk saints; narco saints; media; news; xenophobia; Catholicism; borderlands; Mexico; Texas; United States 1. Introduction

Regarding the borderlands that divide the United States and Mexico, there exists a certain richness of culture that defines the area—a culture not created solely through the division of land but also through the fusion of people. For centuries, both sides have fought over this line, attempted to shift the line further north or south, and patrolled the comings and goings from one side of the line to the other. The line that separates both countries seems incredibly thin and clear for those living further away from it; however, for those living near it, the line becomes broader and hazier. The people living within the haze referred to as “the borderlands” live a life affected by intense, amplified conditions of both countries. These conditions create an environment more susceptible to crime, specifically trafficking and its associated corruption.

Borderland communities impacted by such corruption have a tendency of banding together and seeking refuge within religion and religious practices. For example, one practice consists of praying to Catholic saints, such as San Ramón Nonato, San Judas Tadeo, Santo Niño de Atocha, and Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, for intercession on their behalf—for protection, health, and survival. Yet, in addition to the devotion to canonized saints, another more divergent practice prevails in the borderlands. This practice includes the creation and devotion to folk saints, defined as “very special dead people, beyond the norm in their willingness or capacity to intercede on behalf of their communities” (Graziano 2006, p. 10). Devotion to specific folk saints, such as La Santa Muerte, Jesús Malverde, Juan el Soldado, and Pancho Villa, has become not only more popular within borderland communities but also a focal point of law enforcement, the Catholic Church, and the media. These folk saints share common themes and first appeared during specific historical contexts.

This research evaluates the attention to folk saints in the media during the last ten years (2012–2022), specifically noting their appearance in the top five major print media sources in Texas in comparison to each other, to other Texas print media, and to national newspapers. The evaluation of (narco) folk saint media coverage reveals that many of the themes leading to folk saint creation still prevail in borderland culture today, including issues with the government and its authority, dissatisfaction with the Church, socioeconomic conditions of the lower class, and biases of the U.S. media. Additionally, this article uncovers the unwarranted condemnation and, in some cases, criminalization of Mexico’s syncretic religious practices in the U.S., which is wielded as a weapon against immigrants and Hispanic communities by the media.

2. Media Says, “Narco Saints!”

To understand the relationship between U.S.–Mexico drug trade and folk saints, we must evaluate the label “narco” and its related culture. The drug class “narcotic” refers to drugs commonly used to treat severe pain due to their numbing and paralyzing properties. The abbreviated version of the term, “narco,” in reference to drug activity and those associated, came into use in the mid-twentieth century. Of course, the existence of narcoculture and its significance within Latin American culture and cultural studies were established long before the term was coined. According to Haidar and Herrera (2018), a “lexeme-prolific semantic field” based on drug trafficking emerged, including the terms such as, “narco-world, narco-soap operas, narco-democracy, narco-aesthetics, narco-religion, narcocorridos, narco-banners, narco-cemeteries, and so on” (5, 9). The mainstream media representation of the war on drugs in the U.S. and Mexico often glamorizes the culture surrounding drug trafficking in the borderlands, while the reality is often gruesome and violent.1 U.S. media representations of drug trafficking can be divided into two categories: (1) those that depict a more militaristic approach supporting U.S. foreign intervention and (2) those that hint at U.S. drug consumption as a contributing factor to drug trafficking. Scholars argue that “[n]either of these discusses U.S. involvement in the drug trade in any depth” (12).

Mexican folk saints—such as Jesús Malverde, Juan el Soldado, Pancho Villa, and La Santa Muerte—attract drug traffickers as followers. These four folk saints (along with others) have been labeled “narco saints” and are described as “informal patrons of Mexico’s chief illicit trades: money laundering, smuggling, and, of course, drug trafficking” (Flanagin 2014). The connection between drug traffickers and these folk saints has been described as a type of syncretism between culture, religion, and crime. Chesnut (2012) considers folk saint worship “the fastest-growing religious movement in North America” since the 1980s due in part to the war on drugs, the multifaceted personalities and abilities of folk saints, and the pragmatism of their devotees. La Santa Muerte alone attracts an estimated 10 to 12 million followers in the U.S. and Mexico (Kingsbury and Chesnut 2019). Therefore, we must recognize the wide range of followers attracted to this malleable religious practice. The creation and devotion to folk saints is a grassroots movement that was absorbed into narcoculture and distorted by the media for their target audiences. When U.S. media became aware of the association of these folk saints with cartels and drug traffickers, an abundance of sensationalized articles was published exposing the ironic connection between violence and religion. By doing so, the media ripped these religious figures from their more profound social, cultural, and historical roots and perverted them on the global stage. In essence, narco saints are folk saints, but the reverse is not necessarily true. Narco saints form a smaller, unique population of folk saints.

Whereas reports on violence associated with drug trafficking are predictable, the intersections of religious movements and violence can be considered “dramatic denouements,” or rare newsworthy events (Bromley 2002). The surfacing of narco saints in U.S. media meets the four criteria of newsworthiness as distinguished by Cowan and Hadden (2004). Their model for determining the newsworthiness of religious movements, especially new religious movements (NRMs), consists of the restructuring of previously established models. In short, (new) religious movements alone often are not considered newsworthy. Their crossing of the newsworthiness threshold depends on (1) event negativity, (2) resonance of the event with target news consumers, (3) rarity of the event in the experience of target news consumers, and (4) conceptual clarity or simplicity with which the event may be portrayed (69). Reports of folk saints that meet these criteria tend to be those associated with drug trafficking. Subsequently, U.S. news audiences are presented primarily with violent, fear-mongering representations of these folk saints, referred to as narco saints, through the lens of a new religious movement. This is especially true for news audiences in Texas, the U.S. state sharing the longest border with Mexico. However, folk saints are just one thread in a larger tapestry of Mexican religious syncretism resulting from centuries of colonialism.

2.1. Context

There are dozens of folk saints in Mexico. Due to their intimate nature, we may never know exactly how many exist. For the sake of this essay, we will focus on only four. Deciphering the exact moment that folk saint reverence begins proves difficult, but the process of folk saint creation must start with death. The idea of death in Mexico contrasts with the view held by most in the United States. In his book Death and the Idea of Mexico, anthropologist Lomnitz (2005) refers to death as one of the three main totems of Mexico, the other two being La Virgen de Guadalupe and the Constitution of 1857. According to Lomnitz, the last totem was replaced by Benito Juárez shortly after his death (41). Mexico’s relationship with, or even affinity for, death is not a recent development; the concept can be traced back to pre-Columbian death deities, such as Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacíhuatl, worshipped by indigenous peoples as well as other indigenous religious practices. One example includes the Mexica practice of human sacrifice on the top of the Templo Mayor to specific gods (or goddesses), such as Huitzilopochtli, during the rise of the Aztecs in the early 1300s. A closeness with death was evident in the area before Mexico, as it is known today, ever existed.2 Today, Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration is well-known around the globe. In the U.S., the tradition has been culturally appropriated and usually misses the mark (like Cinco de Mayo celebrations). Kingsbury and Chesnut (2019) provide insights into the correlation between folk saints and death in modern day Mexico, revealing:

While this excerpt pointedly refers to La Santa Muerte’s followers, this description also speaks to the attraction of devotees to other folk saints. The perpetuated histories and personalities of figures such as Jesús Malverde, Juan el Soldado, and Pancho Villa contribute to their folk saint reputations being less judgmental and more understanding of devotees from all walks of life.[F]ollowers include the impoverished, criminals, sex workers, prisoners and members of the gay and transgender communities. The destitute generally live in dangerous neighbourhoods where death is part of everyday life. The desire to worship death for this populace stems in large part from the need to accept death, in order to place a familiar face on and not be fearful when confronted with what many dread. […] God might judge them for the sins they have committed. Death, however, as personified by Santa Muerte, does not judge, according to her followers. Whether one is rich or poor, gay or straight, a recidivist or a law-abiding citizen, death comes to us all. Therefore, devotees believe that Saint Death listens to everyone’s prayers no matter who they are. The marginalised furthermore relate to the folk saint due to her ostracism by the authorities.

Candidates for folk saintdom emerged in early twentieth-century Mexican society during moments of disenfranchisement, and continued devotion to them was spurred by the decades of instability that followed. The Mexican Revolution lasted from 1910 to 1920 as a political rebellion against President Porfirio Díaz and his regime, el Porfiriato. In his book, Gonzales (2002) explains that “[w]idespread loss of land created an economic crisis for peasants, whose desperation led them to take up arms against the seemingly impregnable regime of General Porfirio Díaz, dictator of Mexico since 1876” (1). Gonzales also relates that Díaz’s “[s]killful use of violence, centralization of authority at the expense of local autonomy, and electoral fraud allowed [him] to achieve political supremacy and stability” (5). During his dictatorship, Díaz attempted to modernize Mexico and secure foreign investment at the cost of civil repression. Although the country was more stable than it had been in decades, most people in the nation were still considered rural campesinos. General Díaz’s policies benefited foreign investors and the Mexican upper class, creating a large socio-economic gap in Mexican society. The agrarian sector could barely make a living and was not appropriately represented in government affairs because Díaz replaced local authorities with politicians whose loyalty lay with his regime. During the revolution that eventually overthrew el Porfiriato in 1911 and in the turbulent years that followed, everyday life in Mexican society was brimming with violence, poverty, and distrust. Even the Catholic Church allied with Porfirio Díaz’s regime, causing Mexicans to seek protection and solace elsewhere. Law enforcement, the government, and the Church could not help, so they turned to lo nuestro or “one of us” (Graziano 2006, p. 32). In fact, the nature of folk saints as lo nuestro contradicts the idea of la raza cósmica (or “the cosmic race”), which sustained Mexican identity after the 1910 revolution and during the seventy-year rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Mexico.

2.2. Folk Saint Origins

The creation of a folk saint occurs when a particular miracle is granted based on prayer and devotion to a certain deceased person. Once granted, the deceased is considered miraculous and assumes the role of a folk saint. This process is quite different from that of achieving sainthood in the Catholic church; for that reason, we should note that folk saints are not canonized, nor are they recognized by the Church, but solely by the people. In the borderlands, there are particular elements that spark devotion. As Graziano (2006) explains in Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America:

Jesús Malverde, Juan el Soldado, and Pancho Villa are united by their tragic deaths, which can be traced back to the early 1900s. The years leading up to and following the Mexican Revolution were tormented by constant uprisings and bloodshed. Because of this, there are multiple versions of how each of these folk saints supposedly died; nonetheless, many versions acknowledge that these deaths were a direct result of corrupt law enforcement or the government. Graziano (2006) details the significance of these stories by stating, “The corrupt and abusive authorities who populate these narratives are essential to the formation of folk saints […] The underclasses, like their folk saints, are pushed to the margins and suffer the injustices of social, political, and economic systems that privilege others at their expense” (18). Without a doubt, anyone would consider being hanged or shot to death by the police or assassinated by a group of men supported by the government a “tragic” death. These men died violently; yet, for a death to be considered “tragic” in the eyes of others, there must be a sense of wrongdoing or injustice.One can negotiate religion through the bureaucratic Church—with its dogmatic priests, foreign saints, and proscribed rituals, and expensive fees—or one can appeal to ‘one of us’ who is close to God. In this perspective, folk devotion seems almost a transcendentalization of survival strategies derived from ineffective bureaucracy […] it bypasses institutional channels that have failed and makes its appeal directly to a friend on the inside.(33)

Upon minimal inspection of these three men’s lives, it would be difficult to claim that they were innocent victims or that their deaths were undeserving. For example, Pancho Villa is widely known for living a life of banditry, Jesús Malverde was a thief, and Juan el Soldado was accused of rape and murder (and decapitation) of an eight-year-old child. How is it possible that these men died tragic, unmerited deaths? Graziano (2006) clarifies that “[a]ny crimes that may have been committed by folk saints are dismissed […] and neutralized by excessive punishment. The neutralization—a kind of purge—results from the immeasurably greater criminality of unwarranted or extrajudicial executions” (20). Based on this analysis, Pancho Villa represents the ordinary citizen in an ongoing struggle against the government for basic rights who was wrongfully ambushed and shot seventeen times (Gonzales 2002, p. 201). Jesús Malverde is seen as the “Robin Hood” of Mexico and embodies the attempt to close the gap between upper and lower classes before he was hanged by local law enforcement (Gómez Michel 2014, p. 135). The case of Juan el Soldado differs from the other two in that he was merely considered innocent of his crimes and was wrongly sentenced to death by Ley Fuga, a form of execution in which deadly force is justified by state sanctioned entities, including shooting arrested individuals from behind when they (are instructed to) escape (Vanderwood 2004, p. 189). Since the underclass viewed these men as one of their own in the fight against an unstable government and corrupt law enforcement, their unjust deaths secured their role as martyrs. Many connections have been made between the wrongful deaths of these folk saints and the betrayal and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. For these three martyrs, “True justice is recuperated on high when Christ, himself a victim, receives into sainthood these tragically dead people, misfits among them, because their deaths have purified their lives” (Graziano 2006, p. 23).

Although Jesús Malverde, Juan el Soldado, and Pancho Villa lived and died during or shortly after the Mexican Revolution, they were not venerated as folk saints until more recently. Social conditions in Mexico mirrored those experienced previously during the early to mid-twentieth century, and Mexican people sought protection and guidance from local law enforcement, the government, and a newer force—the narcos. When the Church proved incapable of meeting their spiritual needs, they looked elsewhere. At the turn of the twenty-first century, the rise of folk saints and devotion to them became extremely popular. During this time, a different folk saint developed: La Santa Muerte. Even though La Santa Muerte does not have direct ties to the Mexican Revolution, she can be linked to the idea of death in Mexico during that time. For example, La Catrina, an etching of a stylish female skeleton created by artist José Guadalupe Posada during the first years of the Mexican Revolution, is easily recognizable as the national symbol of death in Mexico today. The image of the folk saint La Santa Muerte is depicted in several different ways, many of which include a mixture of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, La Catrina, and the Grim Reaper. Public manifestations of devotion towards La Santa Muerte began in 2001 on All Saints Day when Doña Queta (Enriqueta Romero) placed a “life-size statue of la Santa outside her house […] in Mexico City […] She had received the statue from her son as a present” (Bigliardi 2016, p. 307). Since then, Doña Queta has assumed the role of caretaker for the statue. People visit La Santa Muerte daily, offer her gifts, and plead for her to grant them protection and safety. Although folk saint devotion to La Santa Muerte surfaced more recently than most folk saints, her origins extend further back on the historical timeline, and a complex debate exists regarding her origins (Pansters 2019). Chesnut (2012) and Kingsbury (2021) contend that the origins of La Santa Muerte date back to pre-Columbian civilizations that worshiped death deities, and her likeness and name were first found in Spanish historical records of Mexico, such as Inquisition documents, during the 1700s. Then, records of La Santa Muerte disappeared for approximately 100 years to later resurface in Mexican and U.S. anthropological findings from the 1940s.

2.3. Criminalizing Religion

The Texas–Mexico border has a long reputation of chaos, crime, and political turmoil. There are four Mexican states that share the Texas border with the United States: Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas. Of these four, Tamaulipas is the easternmost Mexican state that shares a border with the southernmost region of Texas and the Gulf of Mexico. Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, Nueva Ciudad Guerrero, and Matamoros are its well-known cities. In In the Shadow of Saint Death: The Gulf Cartel and the Price of America’s Drug War in Mexico, author and journalist Deibert (2014) states that, “A study by Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) published in late 2012 showed that 80 percent of the businesses in Tamaulipas had been victims of crime, with firearms used in nearly 40 percent of those instances.” The statistics are astounding, especially compared to the national rate of 37.4 percent of all businesses in Mexico that had been victims of crime (229). Drug trafficking involves several other types of corruption, such as money laundering, the selling of governmental information, and bribery, that can be readily detected. Connections between the cartels and the government often are secured with an exchange of money. On the other hand, some corruption is more difficult to trace, such as Pax Mafioso, or the securing of political favor by ignoring the crimes of a certain cartel. For example, under Peña Nieto’s governance, convicted drug traffickers and leaders (many of whom were also accused of murder) were acquitted, released from jail based on technicalities, or simply disappeared (Deibert 2014, p. 231).3 It has been said that in Mexico “there are two governments. A formal one […] And the real one, which for at least seven years has been collecting taxes and decreeing who lives and who dies” (Camarena 2012; my translation). These are living conditions that communities in the borderlands experience daily. Cartels have infiltrated governmental institutions, perpetuating chaos, fear, and mistrust. Communities have nowhere to go to seek protection from the narcos, and they become desperate for more access to, and response from, the divine.

According to Paternostro (1995), historically, the U.S. has ignored Mexico’s role in drug trafficking. Even though Mexico served as a primary gateway of drugs into the U.S., at the beginning of the war on drugs, the country’s counternarcotic task forces fixated on Colombia—the origin of drug production. However, as pressure on the main channel of cocaine entry to the U.S. increased in Florida, Mexico became the most logical alternative route. With this increased wave of smuggling came drug-related political corruption. In the 1990s, “[c]hronic corruption within the PRI, even at the highest levels, [was] widely accepted—even expected—by Mexicans” (42). This acceptability of corruption has continued to grow. Eduardo Valle Espinosa, former Mexican attorney general’s special counternarcotics adviser, labeled Mexico a “narco-democracy” in a 1994 letter to then President Salinas, stating that Mexican politicians serve drug traffickers. Nonetheless, Mexico has not been the only country marked by such a label. For the U.S., this concept was of particular concern considering its shared border with Mexico and Mexico’s role as a major trading partner under NAFTA (43).

The U.S. has an extensive history of acquiring contraband via its southern border and Mexico from its northern. NAFTA lessened the number of illegally imported products into the U.S. However, illicit trade across the border in both directions persists today. Before illegal contraband across the U.S.–Mexico border consisted primarily of drugs, such as marijuana, heroin, and cocaine, the U.S. secured its alcohol from Mexico during Prohibition. As Paternostro (1995) explains, “Being a contrabandista, a smuggler, is a tradition in families that live along the border” (44). By recognizing the region’s long history of illicit trade that continues to affect borderland culture at present, we better understand the intricately extensive influence of cartel and drug trafficking on everyday life in the area, including their impact on (the perceptions of) religious practices.

Over time, the folk saints analyzed in this article have been absorbed into the drug trafficking culture that permeates the Texas–Mexico border. Bunker et al. (2010) provide a helpful, detailed account of these “saints-of-last-resort” and their narco-associations. Their research sheds light on the various spectrums of folk saint devotion and reveals the tendency of cartels to lean toward certain folk saints more than others. In fact, three of the four folk saints that we examine in this article are well-established and recognized as pertaining to specific groups of drug traffickers. Yllescas Illescas (2016) dives even further into the relationship between folk saints and crime in his research regarding La Santa Muerte devotion in the Mexican prison system. His research reveals the complexities of the narco-religious practice with interviews and other firsthand accounts. His study answers the question, “¿De qué sirve ser un devoto de la Santa Muerte durante el encierro?”4 The answers found in Yllescas Illescas data range from La Santa Muerte’s help with internal prison problems (i.e., economic problems and person conflicts with others), with matters outside of prison (i.e., attaining information about family matters or a reduction in their sentence), and with self-improvement (191). This research allows us to better comprehend how these folk saints, especially La Santa Muerte, fit into the world of narco-religion and why devotion to these folk saints is so alluring for drug traffickers and incarcerated individuals.5 In this vein, Kingsbury (2019) reveals how:

Although they may appear incongruous, criminal organizations have long adhered to religious worship and ritual in annex to their nefarious activities. In Latin America, many renowned drug lords have affiliated themselves with official Catholic saints, as well as with folk saints to spiritually sanction their activities. Their devotional activities give narcos the impression of wielding supernatural forces with which to arm and protect themselves in a world characterised by extreme violence and daily uncertainty.(90)

In the last ten years, interest in folk saints and narco saints has continued to increase. Along with the distorted representation of these religious icons, we have witnessed an intentional attempt at clarifying the correlation between folk saints and narcoculture. Although not as popular or readily available to the masses as its media coverage, the topic of folk saints and narco saints has piqued interest in the academic realm. A search for “folk saint” from all databases in EBSCO Publishing Academic Search Ultimate results in 146 total peer-reviewed publications spanning 2012 to 2022.6 The same search parameters for “narco saint” result in four peer-reviewed publications. These data demonstrate an emphasis in academia on folk saints, suggesting that often, “academics and journalists are talking past one another and there is considerable room for more serious dialogue” (Cowan and Hadden 2004). Nevertheless, an example of a more thorough examination of narco saints by the U.S. media includes Ann Neumann’s (2018) Baffler article titled “The Narco Saint: How a Mexican folk idol got conscripted into the drug wars.” Neumann’s piece is a more well-rounded representation of these folk saints published by the media, exemplifying a more successful dialogue between journalists and scholars. She explains the connection between folk saints and the prison system by stating, “Santa Muerte’s suite of protective miracles are indeed what compel men involved—either by economic necessity or by vice—in drug running and kidnapping activities to pray to her. And when these men are arrested, they take Santa Muerte to prison with them […] this fact alone has caused Santa Muerte’s outlaw renown to spread far and wide.” Because of this cycle, La Santa Muerte has become associated with incarcerated individuals.

Even though Mexico’s prison population steadily declined since 2014, the most recent data from 2020 report an increase for the first time in the last ten years. The World Prison Brief discloses a Mexican prison population of 214,231 and an incarceration rate of 169 per 100,000 people (Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research and University of London 2022). These rates are much lower than the U.S. prison population of 2,102,400 and its incarceration rate of 642 per 100,000 people, as recorded most recently in 2018 (Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research and University of London 2019). Despite the decreasing Mexican prison population, the data for crime and homicide rates show an adverse trend. In fact, Mexico’s murder rate is the highest it has been in the last decade. According to the World Population Review (2022), an independent organization without political affiliations, the most recent data for Mexico reveals a 2022 crime index of 54.19 (meaning approximately 54 crimes are reported per 100,000 people in the country), contributing to Mexico’s crime rate, thirty-ninth highest worldwide. For perspective, the average global crime index is 44.74, and the U.S. is ranked with the fifty-sixth highest crime rate at an index of 47.81. The most recent intentional homicide rate reported by the (UNODC) United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2022) for Mexico in the year 2020 is 28.37 compared to the U.S rate of 6.28 and the global average of 7.22 (2022). Mexico’s high crime and (intentional) homicide rates directly correlate with cartel activity and drug trafficking across the border. For those living further away from the U.S.–Mexico border, these offenses are often viewed as inevitable actions carried out by complex and expansive criminal organizations rather than stemming from the impact of neoliberal policies on daily life.

Due in part to the uptick in crime and homicides combined with media interest in certain folk saints and their ties to cartels and drug traffickers, narco saints were put on trial by the United States judicial system. Volokh (2014) of the Washington Post relates how folk saints are controversial topics in the courts regarding the term “tools of the trade” of drug trafficking (i.e., baggies, razor blades, etc.). The 2014 United States v. Medina-Copete case based its argument on a precedent set during the 1992 case United States v. Robinson, which permitted the use of an expert to testify on gang affiliation between folk saint iconography and drug trafficking. In the 2014 case, the court decided that “[d]rawing the connection between a religious icon and drug trafficking is not a straightforward matter” and that even though some drug traffickers may wear folk saint iconography, a concrete connection between the devotees and crime does not exist (Volokh 2014). Nonetheless, the court’s decision in United States v. Medina-Copete illuminates the media’s capability of perpetuating biases against folk saints to the extent of creating a precedent for racially and criminally profiling their followers based on their syncretic religious practices.

Rather than focusing on the popularity of these folk saints in the narco realm, we should be more concerned about the underlying fundamental issues this phenomenon illuminates. As the violence and crime surrounding drug trafficking increase, especially along the Texas–Mexico border, living conditions become increasingly volatile and dangerous. More people turn to folk saints to right the injustices that other institutions have failed to address. Safety, justice, and hope are underlying factors that perpetuate these folk saints for both law-abiding citizens and otherwise. The institutions that should be ensuring safety, justice, and hope, such as governmental agencies and the Church, are failing. The World Bank’s (2020) most recent Poverty and Equity Brief for Mexico from April 2020 reports that 52.4 million people in Mexico (41.9%) are living at various intersections of poverty and social deprivation. On a related note, Kingsbury and Chesnut (2019) relay the Catholic Church’s sharp decline in membership in Latin America since the 1970s. They also explain that the Church “is now haemorrhaging members in the US, where the Catholic percentage of the population dropped from 24 to 21 percent between 2007 and 2014.” These same institutions responsible for meeting the material needs, essential services, and spiritual consolation of their people are condemning and criminalizing the systems that provide the very services that they are neglecting.

2.4. Unpacking the Media’s (Mis)Representations

The condemnation of folk saints is perpetuated by U.S. media outlets. The idea of narco saints combines the U.S. media’s obsession with the war on drugs while reviving the satanic panic. News, magazines, and TV shows have (quite literally) capitalized on narco saints and culture. As recently as May 2019, WSB-TV Channel 2 News (2019) from Atlanta, Georgia, devoted an entire segment to narco saints in the area. In the segment, the owner of a store selling folk saint iconography in Gwinnett County, a suburban county of Atlanta, states, “I know a lot of people who come here to protect themself and I cannot tell which one is from the cartel and which one is not” (3:30–3:41).7 Even though this news segment stresses that most of these folk saint followers are not involved in drug cartels, the interviews with the district attorney, police, U.S. marshals, and even a Baptist pastor provide the audience with more than enough religiously and racially motivated fear and prejudice. Words such as “horrified” and “evil” are used to describe these saints and any devotion to them. The Clayton County district attorney invited her pastor to speak to the police force, thus turning their war on drugs into a war on religion. In his interview, the Baptist pastor states, “It tries to present itself in a good way, even cloaking itself in Christian garb, but it is evil to the very core” (2:19–2:27). However “evil” these narco saints are presented to be in U.S. media, “[t]he irony is clear: U.S. media companies are making bank on stories of Mexico’s lawlessness—a cycle of crime and violence that impoverishes and jeopardizes the lives of Mexicans while laying bare the complicity of the U.S. government for its role in prosecuting the endless drug war south of the border” (Neumann 2018).

Martín (2013) presents another historically prevalent thread to the rising popularity of these narco folk saints along the U.S.–Mexico border that runs parallel to the history of drug trafficking—immigration. She attributes this “increase in popularity in Mexico to the economic crisis of 1994 […] during which the Mexican peso sharply decreased in value and the middle class lost most of its buying power. The crisis intensified Mexican migration to the United States, as many sought to escape ever more precarious economic conditions” (182). According to the most recent Migration Policy Institute (MPI) (2019) analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data in 2019, Texas is home to an “unauthorized population” of 1,739,000, of which Mexico serves as the top country of birth at 67% and the top region for birth is Mexico and Central America at 85%. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s latest report estimates a 1 January 2018 “unauthorized immigrant” population of 11.4 million, which remained roughly unchanged from the prior 2015 report. Of these populations, 55% of undocumented immigrants were from Mexico in 2015, which decreased to less than 50% in 2018. These numbers may correlate with stricter immigration policies and border security. Approximately 15% of the population from Mexico have immigrated since January 2010, and 40% were living in either California or Texas as of 2018 (Baker 2021).

Research has found that many Mexican migrants fleeing dangerous living conditions for the U.S. are folk saint devotees, a contributing factor to folk saint popularity on both sides of the border. A common component among these folk saints is that they have “the potentiality to reconfigure both traditional religion and the structures of conventional society” (Machado et al. 2018). This reconfiguration can be both alarming and unsettling for non-devotees, as witnessed by U.S. media reports. Print news media’s role in upholding and promoting nationalistic ideals is not a new concept. Scholars have scrutinized the role of media in perpetuating xenophobia, stereotyping, and prejudice against immigrants for years. As Kleist et al. (2017) explain:

This trend has been examined in several countries, most notably the United States and South Africa.8 More recently, scholars have analyzed this pattern of anti-immigration discourse in social media.9 In her article “Politics, Media and The U.S.-Mexico Borderlands,” González de Bustamante (2017) examines the U.S. media’s (mis)representation of its southern border from the 1950s to the present day, specifically noting the news media’s contribution to anti-immigration sentiments and militarization efforts along the border. González de Bustamante (2017) also illuminates the role of social media and “fake news” in furthering xenophobia for monetary gain. In fact, the media are responsible for not only the perpetuation of derogatory labels, such as “illegal alien,” but also the creation of others, such as “wetback” (30). The use of dehumanizing language toward immigrants in the media reinforces the dominant anti-immigration power structures, and “[o]ver time, the racialized language of imperialism used to portray migrants in the borderlands helped further the project of political exclusion in the region” (30).10The great nationalisms of the 20th century were largely media-driven fractures between “us” and “them.” The creation of such boundaries is consubstantial to the most fundamental media effect: providing a common experience of space, time, and language. In this sense, all media are “xenophobic” as they provide a specific experience of belonging that may appear to be unique and natural. This is equally true for the most pro-democratic and progressive outlets.(5)

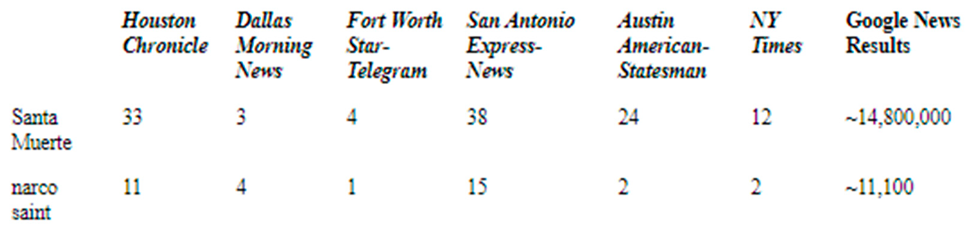

The evidence is compelling when we consider, for example, the reporting rates of the top five Texas major print media sources. The following table quantifies the number of search results for articles published from 11 May 2012 to 11 May 2022.11 The reporting rates are also compared to the New York Times and Google News Results for perspective. As we can see, searches for news articles using the terms “Santa Muerte” (arguably the most notable narco saint) and “narco saint” in the last ten years resulted in significantly more articles for print news media published and circulated closer to the Texas–Mexico border. The (TDC) Texas Demographic Center (2022) illustrates that the majority of Texas’ Hispanic population resides in the southern half of its counties, including Bexar, Travis, and Harris counties, where the San Antonio Express-News, Austin American-Statesman, and Houston Chronicle originate. The Center projects sustained majority Hispanic populations in Bexar and Travis in counties by the year 2030, which will continue to increase.

This information correlates with a broader picture of Texas politics and newsworthiness. Immigration is a point of contention for Texas political parties and campaigns. However, anti-immigration campaigns often prove unsuccessful in states with considerable Latino/a populations and voters (Martin 2010). According to the United States Census Bureau (2021), the Hispanic and Latino/a population comprises 39.7% of the total Texas population. With these data in mind, we can assume that anti-immigration campaigns would prove less successful in states like Texas. Cowan and Hadden (2004) clarify:

Texas news stories regarding folk saints reveal more subtle forms of xenophobia and racism, implying associations among narco saints, drug traffickers, and Mexican immigrants because they meet newsworthy criteria. In the case of narco saints, crossing the newsworthiness threshold consists of encouraging and perpetuating racial biases. This occurs in the media when reports of rare crimes and violence associated with the religious practices of a specific demographic (namely, Latino/a residents) are directed towards a target audience (in this case, a White plurality), thus reinforcing their beliefs. In keeping with this cycle, Texas media sources have weaponized (narco) folk saints to promote the U.S. militarization of the border, restrictions on immigration, prejudice against immigrants, stereotyping of Latino/a communities, and xenophobia. Similar to what we have witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, the news media and social media latch onto a sensational newsworthy story, disseminating and circulating biased, and often harmful, information.12The media are not merely reporters of “dramatic denouements,” silently mirroring events as they unfold. Rather, they are onstage with the rest of the actors, helping to write the emerging cultural script about those events. And, as long as the current structural criteria of newsworthiness remain in place, with regard to new and controversial religious movements, those cultural scripts will continue to be overwhelmingly negative.(78)

In 2011, Fryberg et al. (2011) conducted a case study of print media in Arizona, revealing and quantifying the blatant connection between undocumented immigrants and drug trafficking primarily endorsed by right-wing media in efforts to pass problematic anti-immigration policies. The authors broaden these occurrences to disclose how, in general:

When the media choose to link “illegal immigration to drug cartels, violence, and crime, the media frames immigration as a threat to the safety and security of the American public,” which reinforces and encourages, “negative stereotypes of Mexicans or other Latinas/Latinos as dangerous criminals who are a threat to American values.” (3). In the U.S., the media’s associations between immigrants, specifically Mexican immigrants, and drug trafficking are evident. In Texas, the Latino/a resident population is only a mere 0.5% fewer than the White resident population (Ramsey 2021). Therefore, flagrant anti-immigration political stances would be less successful in a state with such a large Latino/a (voting) population. However, with White Texans as the majority in 65% of congressional districts (compared to the 18.4% Hispanic-majority districts), more camouflaged systems for promoting anti-immigration attitudes have surfaced. Texas print media promotes xenophobia under the veil of religion by associating the state’s largest growing demographic with the fastest growing religious movement in North America, thus linking the idea of Mexican immigration into Texas to the violence of drug trafficking. This assertion is affirmed by the top five major Texas print media’s tendency to embed suggestions and advertisements for La Santa Muerte and narco saint articles within articles related to crime, immigration, and Latino/a-related content. For example, articles and editorials considered similar to the topic the reader is currently consuming are advertised as “related” or “more” at the top or bottom of the web page or within the article itself at certain breaks, encouraging the reader’s click and implying the topics are related.The media both reflects and contributes to the ways in which the debate over illegal immigration is processed and understood. Specifically, the way in which the media frames arguments plays an important role in how social and political issues, such as immigration, are presented in the national debate, as well as how people respond to this controversial issue.(3)

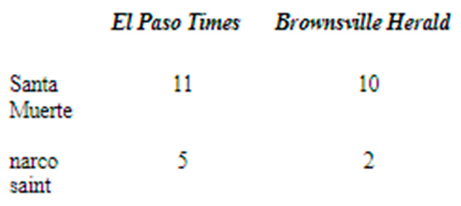

Print media sources on the border, like the El Paso Times and the Brownsville Herald, published significantly fewer news articles on folk saints between 11 May 2012–11 May 2022.

These data interact with the idea of (voter) population demographics. According the TDC, El Paso County has a White population of 105,246 and a Hispanic population of 658,134; Cameron County (where Brownsville is located) has a White population of 43,427 and a Hispanic population of 357,747. In comparison, White populations in the counties hosting the top five major print media sources range from 517, 644 (Travis County) to 1,349,646 (Harris County), with a mean White population of approximately 821,648. These numbers further reaffirm the criteria for newsworthiness, especially regarding rarity of the event and resonance of the event with the target audience. Namely, media outlets are more/less sympathetic to folk saints depending on the closeness of the media outlet to the dominant population. In areas closer to the border, with larger Latino/a populations, folk saints are not necessarily newsworthy media topics. But, in urban areas with comparatively fewer Latino/a residents and/or larger White populations, these Latino/a residents become connected with crime in the public mind. Nevertheless, the El Paso Times also showed a tendency to insert “related” articles on narco folk saints within publications related to crimes perpetuated by Hispanic individuals (such as its 2018 article titled “Deputies: Heroin delivered in gift bag ends in 2 arrests in East El Paso”) and against Hispanic communities (like its 2018 article “Suspect in El Paso triple-murder was on probation; 2 victims had been arrested”). These strategic suggestions are not only practiced within the top five Texas major print media sources or areas with large White populations but rather are evidence of systemic media biases in Texas.

The effects of print media stories regarding narco folk saints impact marginalized communities along the border, where dominant anti-immigration power structures clash with the realities of everyday lives divided by a political boundary. The media’s recent attention to these narco saints is yet another attempt to uphold the “‘moral geography’ of the region: one that has been defined by nationalism, nativism, and racism” (González de Bustamante 2017, p. 30). In our current political climate, with the surge of xenophobia, anti-immigration/anti-refugee sentiments, and replacement theory adherents, “one effect is obvious: the normalization of intolerance. To explain enduring stereotypes, researchers point to the biased representations of minorities and foreigners in popular culture” (Kleist et al. 2017, pp. 4–5). I argue that these prejudiced representations also include Texas print media’s attention to syncretic religious practices along its border and within its Hispanic communities.

3. Conclusions

Borderland folk saints have a rich and complicated history. Only a small portion of these folk saints—deemed narco saints—meet the criteria for newsworthiness. By observing the attention they receive from Texas news articles, we can see that current social conditions resonate with those present at the time these folk saints originally appeared. In the past two decades, cartels and drug traffickers have been responsible for furthering this brutality, distrust, and disorder in the borderlands. Having been on the inside, ex-narco Juan Pablo García reveals that “gang culture is a consequence of ‘broken social fabric’[…] You can’t fix this with more soldiers and police” (Tucker 2017). These conditions generate more folk saint devotees and perpetuate the cycle. For more than a century, devotees relate to folk saints’ personal struggles and cruel environments and turn to them when other institutions, such as the government and the Church, fail to meet their material and spiritual needs. These folk saints serve as sacred intermediaries, and presuming narco affiliation among immigrants solely for demonstrating reverence to lo nuestro is racial profiling and demonstrates disregard and injustice to the centuries of Mexico’s syncretic religious practices.

Folk saints that have been absorbed into narcoculture continue to fulfill their original folk saint roles for others. For example, La Santa Muerte may be considered a folk saint to one and a narco saint to another. The attention to and perpetuation of these narco folk saints by the media often distort and sensationalize a very common practice, recklessly overlooking the intricacy of the U.S. war on drugs, illicit drug trade along the U.S.–Mexico border, immigration policies, covert forms of racism, and their effects on everyday life.

Unlike the political boundary separating Texas from Mexico, a fixed line does not exist separating a folk saint from a narco saint. These categories are fluid and often ambiguous. Regardless of whether these figures are perceived as folk saints or narco saints, their fundamental purpose remains the same. Over the past decade, Texas print media have contributed greatly to the perception of narco saints, referring to these unconventional saints as “evil” and breeding fear and ignorance surrounding this rising religious movement. However, these same news sources also reveal the more rooted societal issues affecting the borderlands—the circumstances causing citizens to turn to these figures in the first place. Rather than perceiving and presenting these narco folk saints as the cause of corruption and illicit drug trade, we should regard them as the effect and, in some cases, the figurative Band-Aid.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For data on torture, beheading, and other forms of violence by drug traffickers in Mexico, see Bunker et al. (2010). For information regarding violence and folk saints, see Park (2019). |

| 2 | See Coe et al. (2019), Chapter 2 of Rabasa (2010), and Rabasa (2011). |

| 3 | For more history of drug traficking, governmental corruption, and narcoculture in Mexico, see Campos (2012) and Smith (2021). |

| 4 | “What is the use of being a La Santa Muerte devotee during incarceration?” (my translation). |

| 5 | For more information regarding folk saints’ histories and devotion, including Santa Muerte and Jesús Malverde, see works by Bastante, Bigliardi, Chesnut, Garces Marrero, Hernández, Kingsbury, Kristensen, Pansters, Park, Perdigón Castañeda, Price, and Roush. |

| 6 | Results reflect publications available as of 13 May 2022. |

| 7 | Transcriptions not provided by WSB-TV. All transcriptions are carried out by the author. |

| 8 | Articles related to news media’s xenophobia, specifically in South Africa and the U.S., include Augustine and Augustine (2012); Danso and McDonald (2001); Tarisayi and Manik (2020); and Vos et al. (2021). |

| 9 | Recent publications on the topic include Ekman (2019); de Saint Laurent et al. (2020); and Nortio et al. (2021). |

| 10 | For a critical discourse analysis of the media’s linguistic manipulation towards immigrants, see Hart (2013). |

| 11 | Search results as of 11 May 2022. |

| 12 | Recently, xenophobia, stereotyping, and anti-immigration have been studied in those who consume social media as news sources regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. See Ahmed et al. (2021). |

References

- Ahmed, Saifuddin, Vivian Chen Hsueh-Hua, and Arul Indrasen Chib. 2021. Xenophobia in the Time of a Pandemic: Social Media Use, Stereotypes, and Prejudice against Immigrants during the COVID-19 Crisis. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 33: 637–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, Roslyn Satchel, and Jonathan C. Augustine. 2012. Religion, Race, and the Fourth Estate: Xenophobia in the Media Ten Years after 9/11. Tennessee Journal of Race, Gender, & Social Justice 1: 1–58. Available online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/rgsj/vol1/iss1/3 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Baker, Bryan. 2021. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2015–January 2018; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Available online: www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/immigration-statistics/Pop_Estimate/UnauthImmigrant/unauthorized_immigrant_population_estimates_2015_-_2018.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Bigliardi, Stefano. 2016. La Santa Muerte and her interventions in human affairs: A theological discussion. Sophia 5: 303–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, David G. 2002. Cults, Religion, and Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, Pamela L., Lisa J. Campbell, and Robert J. Bunker. 2010. Torture, beheadings, and narcocultos. Small Wars & Insurgencies 21: 145–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarena, Salvador. 2012. Torturada y asesinada una exalcaldesa mexicana. El País. November 19. Available online: www.elpais.com/internacional/2012/11/17/actualidad/1353152160_415576.html (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Campos, Isaac. 2012. Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chesnut, Andrew. 2012. Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, Michael D., Javier Urcid, and Rex Koontz. 2019. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, Douglas E., and Jeffrey K. Hadden. 2004. God, Guns, and Grist for the Media’s Mill: Constructing the Narratives of New Religious Movements and Violence. Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 8: 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, Ransford, and David A. McDonald. 2001. Writing xenophobia: Immigration and the print media in post-apartheid South Africa. Africa Today, 115–37. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/4187436 (accessed on 20 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- de Saint Laurent, Constance, Vlad Glaveanu, and Claude Chaudet. 2020. Malevolent creativity and social media: Creating anti-immigration communities on Twitter. Creativity Research Journal 32: 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibert, Michael. 2014. In the Shadow of Saint Death: The Gulf Cartel and the Price of America’s Drug War in Mexico. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, Mattias. 2019. Anti-immigration and racist discourse in social media. European Journal of Communication 34: 606–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagin, Jake. 2014. The Rise of the Narco-Saints: A New Religious Trend in Mexico. The Atlantic. September. Available online: www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/09/big-in-mexico/375060/ (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Fryberg, Stephanie A., Nicole M. Stephens, Rebecca Covarrubias, Hazel Rose Markus, Erin D. Carter, Giselle A. Laiduc, and Ana J. Salido. 2011. How the media frames the immigration debate: The critical role of location and politics. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 12: 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Michel, Gerardo. 2014. The Cult of Jesús Malverde: Crime and Sanctity as Elements of a Heterogeneous Modernity. Latin American Perspectives 41: 202–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Michael J. 2002. The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1940. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- González de Bustamante, Celeste. 2017. Politics, Media and The US-Mexico Borderlands. Voices of Mexico. January 26. Available online: www.researchgate.net/profile/Celeste-Bustamante/publication/318025287_Politics_Media_and_the_US-Mexico_Borderlands/links/5957e064aca272c78abc886c/Politics-Media-and-the-US-Mexico-Borderlands.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Graziano, Frank. 2006. Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haidar, Julieta, and Eduardo Chávez Herrera. 2018. Narcoculture? Narco-trafficking as a Semiosphere of Anticulture. Semiótica 222: 133–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Christopher. 2013. Argumentation meets adapted cognition: Manipulation in media discourse on immigration. Journal of Pragmatics 59: 200–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research, and University of London. 2019. World Prison Brief: United States of America. Available online: www.prisonstudies.org/country/united-states-america (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research, and University of London. 2022. World Prison Brief: Mexico. Available online: www.prisonstudies.org/country/mexico (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Kingsbury, Kate. 2019. Chapter 10: The Knights Templar Narcotheology: Deciphering the Occult of a Narcocult. In Los Caballeros Templarios de Michoacán: Imagery, Symbolism, and Narratives. Edited by Robert J. Bunker and Alma Keshavarz. (Small Wars Journal). Bethesda: Small Wars Foundation, pp. 89–94. Available online: www.researchgate.net/publication/342720665_LOS_CABALLEROS_TEMPLARIOS_DE_MICHOACAN_-THE_KNIGHTS_TEMPLAR_OF_MICHOACAN_IMAGERY_SYMBOLISM_AND_NARRATIVES (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Kingsbury, Kate. 2021. Santa Muerte. World Religions and Spirituality Project. Available online: wrldrels.org/2021/03/27/santa-muerte-2/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Kingsbury, Kate, and Andrew Chesnut. 2019. The Church’s life-and-death struggle with Santa Muerte. Catholic Herald. Available online: https://catholicherald.co.uk/the-churchs-life-and-death-struggle-with-santa-muerte/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Kleist, J. Olaf, Antony Loewenstein, Dominique Trudel, Ekaterina Zabrovskaya, and Sydette Harry. 2017. What Role Does the Media Play in Driving Xenophobia? World Policy Journal 34: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lomnitz, Claudio Zamudio Vega. 2005. Death and the Idea of Mexico. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, Daisy L., Bryan S. Turner, and Trygve Eiliv Wyller. 2018. Borderland Religion: Ambiguous Practices of Difference, Hope, and Beyond. Oxfordshire: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Michel. 2010. Candidates Use Migration as Political Weapon. National Public Radio (NPR). October 20. Available online: www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=130699164 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Martín, Desirée A. 2013. Borderlands Saints: Secular Sanctity in Chicano/a and Mexican Culture. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Migration Policy Institute (MPI). 2019. Profile of the Unauthorized Population: Texas. Available online: www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/TX (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Neumann, Ann. 2018. The Narco Saint: How a Mexican folk idol got conscripted into the drug wars. Baffler 38: 50–57. Available online: www.thebaffler.com/salvos/the-narco-saint-neumann (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Nortio, Emma, Miira Niska, Tuuli Anna Renvik, and Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti. 2021. ‘The nightmare of multiculturalism’: Interpreting and deploying anti-immigration rhetoric in social media. New Media & Society 23: 438–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansters, Wil G., ed. 2019. La Santa Muerte in Mexico: History, Devotion, and Society. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jungwon. 2019. Bare Life in Contemporary Mexico: Everyday Violence and Folk Saints. In A Post-Neoliberal Era in Latin America? Edited by Daniel Nehring, Magdalena López and Gerardo Gómez Michael. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp. 243–59. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/25177/1004913.pdf?sequence=1#page=254 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Paternostro, Silvana. 1995. Mexico as a Narco-democracy. World Policy Journal 12: 41–47. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/40209397 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Rabasa, José. 2010. Without History: Subaltern Studies, the Zapatista Insurgency, and the Specter of History. Pittsburg: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rabasa, José. 2011. Tell Me the Story of How I Conquered You: Elsewheres and Ethnosuicide in the Colonial Mesoamerican World. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, Ross. 2021. Analysis: Texas population has changed much faster than its political maps. Texas Tribune. December 8. Available online: www.texastribune.org/2021/12/08/texas-redistricting-demographics-elections/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Smith, Benjamin T. 2021. The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tarisayi, Kudzayi Savious, and Sadhana Manik. 2020. An unabating challenge: Media portrayal of xenophobia in South Africa. Cogent Arts & Humanities 7: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Demographic Center. 2022. Population by Race and Ethnicity in Texas Counties: Texas Population Projections Program. Available online: https://idser.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=3ca585f84ec34b4d936beb54a9c57416 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Tucker, Duncan. 2017. ‘I can’t believe how I used to live’: From gang war to peace treaties in Monterrey. Guardian. February 22. Available online: www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/feb/22/gang-war-peace-treaties-monterrey-mexico (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2022. Homicide by Country Data. Available online: https://dataunodc.un.org/content/homicide-country-data (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- United States Census Bureau. 2021. QuickFacts: Texas. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/TX (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Vanderwood, Paul J. 2004. Juan Soldado: Rapist, Murderer, Martyr, Saint. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Volokh, Eugene. 2014. Narco-saints and expert evidence. Washington Post. July 8. Available online: www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2014/07/08/narco-saints-and-expert-evidence/ (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Vos, Saskia R., Cho Hee Shrader, Vanessa C. Alvarez, Alan Meca, Jennifer B. Unger, Eric C. Brown, Ingrid Zeledon, Daniel Soto, and Seth J. Schwartz. 2021. Cultural stress in the age of mass xenophobia: Perspectives from Latin/o adolescents. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 80: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. 2020. Poverty and Equity Brief: Mexico. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/33EF03BB-9722-4AE2-ABC7-AA2972D68AFE/Global_POVEQ_MEX.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- World Population Review. 2022. Crime Rate by Country 2022. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/crime-rate-by-country (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- WSB-TV Channel 2 News. 2019. Drug Cartels Worship ‘Narco Saints’, Making Them More Dangerous, DEA Says. Atlanta: Cox Media Group. Available online: www.wsbtv.com/news/local/drug-cartels-worship-evil-idols-making-them-more-dangerous-dea-says/946859527/ (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Yllescas Illescas, Jorge Adrián. 2016. “La Santa Muerte: Historias de vida y fe desde la cárcel.” MA tesis. Repositorio Institucional de la UNAM. Available online: https://132.248.9.195/ptd2016/enero/0740019/0740019.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).