The Normative World of Memes: Political Communication Strategies in the United States and Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

Ecuador and the United States: Political and Cultural Common Aspects

3. Materials and Methods

Units of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Let’s Try to Be Serious: The First American Debate

4.2. Andrés, Don’t Lie Again: The Ecuadorian Debate

stems from the tolerance of the moderators and the few reactions that are produced to repair their image by the offended speakers (…) The insult, expressed especially by improper structures, thus becomes a configuring feature of journalistic debates with political content, within their consideration as spaces that promote aggressiveness and controversy.

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alatas, Vivi, Arun G. Chandrasekhar, Markus Mobius, Benjamin A. Olken, and Cindy Paladines. 2019. When Celebrities Speak: A Nationwide Twitter Experiment Promoting Vaccination in Indonesia. arXiv arXiv:1902.05667. [Google Scholar]

- Arterton, Christopher. 1987. Teledemocracy: Can Technology Protect Democracy? Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Barberi, Daniela, and Augusto Reina. 2020. ¿Cuál es el Impacto de Los Debates Presidenciales? Buenos Aires. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344933189_Cual_es_el_impacto_de_los_debates_presidenciales_Resultados_del_proyecto_PulsarUBA_sobre_el_debate_presidencial_de_Argentina_2019 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2012. The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics. The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics. Information, Communication & Society 15: 739–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal, Salomé, Eva Campos-Domínguez, and Marta Redondo. 2014. Media Prosumers in Political Communication: Politainment on YouTube. Comunicar 22: 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, Michael. 2005. Laughter and Ridicule: Towards a Social Critique of Humor. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsell, David S. 2017. Political Campaign Debates. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication. Edited by Kate Kenski and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, Jan, and Edson C. Tandoc. 2015. Why We Retweet: Factors Influencing Intentions to Share Sport News on Twitter. International Journal of Sport Communication 8: 212–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branagan, Marty. 2007. Activism and the Power of Humor. Australian Journal of Communication 34: 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Breuninger, Kevin, and Christina Wilkie. 2020. Vicious First Debate between Trump and Biden Offered Little on Policy, Lots of Conflict. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/29/first-presidential-debate-highlights-trump-vs-biden-.html (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Brown, Abram. 2020. Presidential Debate: 8 Perfect Twitter Responses to the Trump-Biden Chaos. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/abrambrown/2020/09/30/presidential-debate-8-perfect-twitter-responses-to-the-trump-biden-chaos/?sh=6e36321ccfdd (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Castañeda, Walter M. 2015. Los Memes y El Diseño: Contraste Entre Mensajes Verbales y Estetizantes. Kepes 12: 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura, and Andrea Carrillo-Andrade. 2019. Post-Truth and Disinformation: Using Discourse Analysis to Understand the Creation of Emotional and Rival Narratives Post-Verdad y Desinformación. Uso del Análisis del Discurso Para Comprender la Creación de Narrativas Emocionales y Rivales en Brexit Pó 10: 125–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas, Viktor, Fernanda Freire, Daniel Rios, and Dandara Magalhaes. 2019. Political Memes and the Politics of Memes: A Methodological Proposal for Content Analysis of Online Political Memes. First Monday 24: 7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culpeper, Jonathan. 1996. Towards an Anatomy of Impoliteness. Journal of Pragmatics 25: 349–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailymail. 2020. Internet Explodes with Memes as Despairing Viewers Watch Farcical Contest between Trump and Biden. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8788455/Internet-explodes-memes-Trump-Biden-debate.html (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Dawkins, Richard. 1989. The Selfish Gene, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michael. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Edited and Translated by Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- González Sanz, Marina. 2010. Las Funciones del Insulto en Debates Políticos Televisados. Discurso & Sociedad 4: 828–52. [Google Scholar]

- Google. 2021. Encontrar Información Mediante el Rastreo. Available online: https://www.google.com/intl/es/search/howsearchworks/how-search-works/organizing-information/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Highfield, Tim. 2016. Social Media and Everyday Politis. Ebook. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, J. Brian, Mitchell Mckinney, Joshua Hawthorne, and Matthew Spialek. 2013. Frequency of Tweeting During Presidential Debates: Effect on Debate Attitudes and Knowledge. Communication Studies 64: 548–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel. 1992. The Third Wave. Democratization in the Twentieth Century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry, Katie Clinton, Ravi Purushotma, Alice J. Robison, and Margaret Weigel. 2006. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Chicago: MacArthur. Available online: https://www.macfound.org/media/article_pdfs/jenkins_white_paper.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, Carey, Jeff Bezemer, and Kay O’Halloran. 2016. Introducing Multimodality. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Davi. 2007. Mapping the Meme: A Geographical Approach to Materialist Rhetorical Criticism. Communication & Critical/Cultural Studies 4: 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Know Your Meme. 2020. That Debate Was the Worst Thing I’ve Ever Seen. Available online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/that-debate-was-the-worst-thing-ive-ever-seen (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- La Verdad. 2021. Lo Mejor del Debate: Los Memes. Aquí te Mostramos Algunos. Available online: https://www.laverdad.ec/entretenimiento/2021/3/22/lo-mejor-del-debate-los-memes-aqui-te-mostramos-algunos-5591.html (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Loaiza, Yalilé. 2019. El Insulto Político en el Ecuador, Su Historia y Sus Abanderados. Available online: https://gk.city/2019/08/05/insulto-politico-ecuador/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- López-Paredes, Marco, and Vanessa Oñate. 2020. La Memética Como Lenguaje Icónico de Nuevas Narrativas en las Redes Sociales. Redes Sociales y Ciudadanía 10: 729–34. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/44328235/La_memética_como_lenguaje_icónico_de_nuevas_narrativas_en_las_redes_sociales?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Manin, Bernard. 1997. The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marketing Web Consulting. 2020. Buscadores Más Utilizados en el Mundo: No Está Solo Google. Available online: http://marketingwebconsulting.uma.es/buscadores-mas-utilizados-en-el-mundo-no-esta-solo-google/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Marwick, Alice. 2013. Memes. Contexts 12: 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, Mitchell S., J. Brian Houston, and Joshua Hawthorne. 2013. Social Watching a 2012 Republican Presidential Primary Debate. American Behavioral Scientist 58: 556–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, Ryan. 2016. The World Made Meme. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, Albertina. 2021. Desempeño vs. Impacto: Un Modelo Comunicacional Aplicado a la Política Digital. Rafael Correa, Cristina Fernández y Nicolás Maduro. Querétaro: Inteliprix. [Google Scholar]

- O’Halloran, Kay, and Bradley Smith. 2014. Multimodal Studies: Exploring Issues and Domains. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Marla A., and Barry Bozeman. 2018. Social Media as a Public Values Sphere. Public Integrity 20: 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, Joel. 2020. ‘It’s So Hard Not to Be Funny in This Situation’: Memes and Humor in U.S. Youth Online Political Expression. Television and New Media 21: 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Tornero, José Manuel. 2008. Jenkins: La Convergencia Mediática y la Cultura Participativa. Perspectivas. Available online: http://www.jmpereztornero.eu/2008/09/21/jenkins-la-convergencia-mediatica-y-la-cultura-participativa/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Phillips, Whitney, and Ryan Milner. 2017. The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Cambridge: Polity Pr. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, Fernando. 2009. Una Mercancía Irresistible. El Cine Norteamericano y Su Impacto En Chile, 1910–1930. Historia Crítica 38: 46–69. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/811/81112312005.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2021). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ryan, Charlotte, and William A. Gamson. 2006. The Art of Reframing Political Debates. Contexts 5: 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, Giovanni. 1998. Homo Videns. La Sociedad Teledirigida. Mexico City: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Scolari, Carlos. 2008. Hipermediaciones: Elementos Para Una Teoría de la Comunicación Digital Interactiva. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- SEO Quito. 2016. SEM: Google No Es Todo. Available online: https://seoquito.com/sem-google-no-es-todo/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Shifman, Limor. 2013a. Memes in a Digital Culture. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, Limor. 2013b. Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 18: 362–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifman, Limor, Hadar Levy, and Mike Thelwall. 2014. Internet Jokes: The Secret Agents of Globalization? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19: 727–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, Robert A. 2014. Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stelter, Brian. 2020. Trump-Biden Clash Was Watched by at Least 73 Million Viewers. CNN Business. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/09/30/media/first-presidential-debate-tv-ratings/index.html (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Tay, Geniesa. 2012. Embracing LOLitics. pp. 1–236. Available online: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/7091 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Tkacheva, Olesya, Lowell H. Schwartz, Martin C. Libicki, Julie E. Taylor, Jeffrey Martini, and Caroline Baxter. 2013. Internet Freedom and Political Space. Santa Monica: Rand, pp. 17–42. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt4cgd90.9 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Troi, Ernesto, and Alvarado Chávez. 2018. Los Memes Como Manifestación Satírica de la Opinión Pública en la Política Ecuatoriana: Estudio del Caso ‘Rayo Correizador’. Master’s thesis, Universidad Casa Grande, Guayaquil, Ecuador; pp. 1–135. [Google Scholar]

- Weldes, Jutta, and Christina Rowley. 2015. So, How Does Popular Culture Relate to World Politics? In Popular Culture and World Politics: Theories, Methods, Pedagogies. Edited by Federica Caso and Caitlin Hamilton. Bristol: E-International Relations, pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Analysis for Political Memes | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Diffuse at the micro level but shape the macrostructure of society | Persuasive memes, grassroots action memes; and public discussion memes | Persuasive memes: Propositional rhetoric or pragmatic appeal; Seducing or threatening rhetoric or emotional appeal; Ethical and moral rhetoric or ideological appeal; Critical rhetoric or appeal to the source’s credibility. Grassroots action memes: Dynamics of collective or hybrid connective action and networks curated by organizations. Public discussion memes: Political commonplace; Literary or cultural allusions; Jokes about political characters; Situational jokes. |

| 2. Cultural items that people can potentially imitate | Content, form, and stance | Content: referencing both the ideas and the ideologies conveyed by it. Form: physical message, perceived through our senses. Stance: when re-creating a text, users can decide to imitate a specific position that they find appealing or use an utterly different discursive orientation. |

| 3. Travel through competition and selection | Scope | Sticky (unified experience) and spreadable (diversified) mentality |

| Meme 1 | Meme 2 |

|---|---|

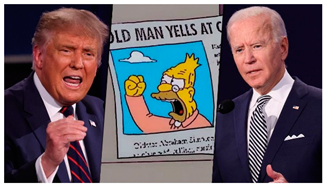

|  |

| Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Cartoon of grandpa Simpson, under the title “Old man yells at cloud”, surrounded by the pictures of Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Critical. Scope: First result under the search engine “debate Trump Biden meme”. In this case, 109 interactions from the original meme. | Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Actor Mark Hamill, who interprets Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars saga; The Star Wars Holiday Special (a spin-off). Critical. Scope: 1,000,000 likes and 97,000 comments. |

| Meme 3 | Meme 4 |

|---|---|

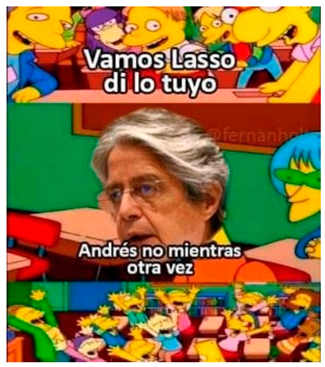

|  |

| Copy: “Come on, Lasso, say the line”; “Andrés, don’t lie again”. Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Frame series of a famous chapter of The Simpsons with Lasso’s catchy phrase against Arauz. Scope: First result under the search engine “debate Lasso Arauz meme”; part of Meme Generator | Copy: If I were the moderator #PresidentialDebateEC. “Quit talking and hit him” Classification: Public discussion memes Cultural items: Frame of the famous series “Malcolm in the Middle” with Dewey (the youngest brother” saying, “Quit talking and hit him”. Scope: More than 1000 likes, 412 retweets, and 11 comments. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Paredes, M.; Carrillo-Andrade, A. The Normative World of Memes: Political Communication Strategies in the United States and Ecuador. Journal. Media 2022, 3, 40-51. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010004

López-Paredes M, Carrillo-Andrade A. The Normative World of Memes: Political Communication Strategies in the United States and Ecuador. Journalism and Media. 2022; 3(1):40-51. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Paredes, Marco, and Andrea Carrillo-Andrade. 2022. "The Normative World of Memes: Political Communication Strategies in the United States and Ecuador" Journalism and Media 3, no. 1: 40-51. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010004

APA StyleLópez-Paredes, M., & Carrillo-Andrade, A. (2022). The Normative World of Memes: Political Communication Strategies in the United States and Ecuador. Journalism and Media, 3(1), 40-51. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia3010004