1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of urban areas worldwide has significantly altered local climates, with profound implications for environmental sustainability, public health, and urban resilience. Among the most notable effects of urbanization is the Urban Heat Island (UHI) phenomenon, defined here as the near-surface air temperature difference between urban areas and nearby rural (or non-urbanized) reference areas. This warming, where urban areas exhibit higher temperatures than their rural surroundings, is primarily due to anthropogenic heat emissions, reduced evapotranspiration, and changes in the surface energy balance. For the purpose of this review, which focuses on near-surface modeling (e.g., 2 m air temperature), the discussion of UHI primarily refers to the thermal differences observed within the Urban Canopy Layer (UCL), the air layer extending from the ground to roughly the mean building height [

1]. Beyond temperature anomalies, urbanization also influences wind patterns, humidity levels, and precipitation regimes, further intensifying the environmental burdens faced by urban populations. Accurately modeling these urban climate phenomena is essential for understanding their causes, predicting future impacts, and designing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies. However, a persistent challenge in urban climate modeling lies in the accurate representation of the complex and heterogeneous urban landscape. Traditional land-use and land-cover (LULC) datasets often lack the spatial and morphological specificity required to capture the nuanced interactions between urban form and local climate dynamics. Addressing these limitations is critical to improving the accuracy and decision relevance of urban climate models for decision-making and urban planning.

In response to this data gap, Stewart and Oke [

2] introduced the Local Climate Zone (LCZ) classification system, a standardized framework that categorizes urban and rural landscapes based on their morphological and thermal characteristics. This system includes ten built-up zones (e.g., compact high-rise, open low-rise) and seven natural land cover types (e.g., dense trees, water bodies), each defined by characteristic ranges of building height, density, surface roughness, albedo, and thermal admittance. The LCZ framework is particularly suited for urban climate modeling because it provides a thermally homogeneous classification system that can be integrated into a variety of numerical models. The World Urban Database and Access Portal Tools (WUDAPT) initiative further supports the use of LCZs by offering a standardized methodology to generate LCZ maps using open-source satellite imagery and volunteered geographic information [

3]. These maps provide a comprehensive and globally consistent dataset that facilitates the integration of LCZs into urban canopy models (UCMs) embedded within mesoscale and microscale climate models.

It is important to note that while the LCZ framework offers a standardized and globally accessible solution for urban classification, it is vital to distinguish it from high-resolution, geometry-based approaches. In regions where detailed Geospatial Information System (GIS) data are available (predominantly in North America and Europe), models like WRF can utilize the National Urban Database and Access Portal Tool (NUDAPT) approach. These ‘geometry-based’ inputs represent the upper tier of urban canopy representation, offering higher physical fidelity than the ‘proxy-based’ LCZ archetypes [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, the LCZ framework remains the most viable and complete approach for multi-city comparisons and for regions lacking detailed urban morphology databases.

The integration of LCZs has significantly enhanced the performance of urban climate models, enabling more accurate simulations of urban heat islands, extreme weather events, air quality, and human thermal comfort. Several advanced climate models have adopted LCZ classifications to improve their representation of urban landscapes. Among these, the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model is one of the most widely used due to its flexibility and advanced urban parameterization schemes, including the Single-Layer Urban Canopy Model (SLUCM), Building Effect Parameterization (BEP), and Building Energy Model (BEM) [

9]. These schemes allow WRF to model surface-atmosphere interactions, anthropogenic heat fluxes, and the impact of urban morphology on local and regional climates. Other models, such as MUKLIMO_3, COSMO, and SURFEX, have also incorporated LCZs through specialized parameterization schemes, allowing for the analysis of long-term climate projections and the evaluation of urban planning interventions.

Despite its growing adoption, the use of LCZs in urban climate research remains an evolving field. Over the past decade, from 2013 to late 2024, the application of LCZs has expanded significantly, transitioning from an experimental concept to a widely accepted classification standard in urban climate studies. This rapid expansion has recently been synthesized in several significant review articles that cover much of the same time period. For example, Han et al. [

10] provided a critical review focusing on the methodological progress and persisting challenges of LCZ mapping, while Li et al. [

11] offered a detailed bibliometric analysis of application trends across multiple fields. While reinforcing their findings on general challenges, such as data quality and geographical bias, the present review offers a distinct and necessary contribution by shifting the focus from LCZ methodology and bibliometric trends to operational modeling complexity. Specifically, this article provides the first systematic analysis of the division of labor and functional specialization among various major prognostic and diagnostic urban climate model families (e.g., WRF, SURFEX, PALM-4U) using a novel three-tiered application maturity categorization; Category 1 focuses on model testing and evaluation, examining studies that have validated and assessed the accuracy of LCZ-based classifications and their integration into urban climate models. Category 2 addresses real-world applications, reviewing studies that have implemented LCZs in scenarios such as UHI reduction, climate adaptation strategies, and urban planning initiatives. Finally, Category 3 captures expansion beyond urban climate studies, highlighting the increasing use of LCZs in fields such as air pollution modeling, hydrology, and remote sensing.

This approach allows us to deliver a unique, practical synthesis of the technical requirements and model-specific limitations inherent in advancing LCZ-integrated climate simulations. In general, this review aims to consolidate existing knowledge on the use of LCZs in urban climate research, providing a systematic overview of how LCZs have become a common method for urban environmental classification. While this study incorporates core elements of systematic review methodology, such as predefined search strings and inclusion criteria, it adopts a semi-systematic approach rather than a strictly protocol-bound PRISMA design. This broader interpretive scope is justified by the need to synthesize a decade of diverse applications across multiple modeling families, where a rigid systematic protocol might overlook the nuanced technical transitions from experimental testing to operational planning.

By analyzing the trajectory of LCZ adoption in urban climate research, this review aims to highlight the strengths and limitations of existing studies, identify emerging trends, and propose future directions for LCZ-based modeling. As urban areas continue to evolve under the pressures of climate change and rapid urbanization, understanding the role of LCZs in improving climate model accuracy will be essential for shaping more resilient and sustainable cities. By systematically reviewing the literature and categorizing studies based on their methodological focus, this review provides a comprehensive understanding of how LCZs have evolved into a standard method in urban climate modeling. It establishes a foundation for future research by outlining key developments, assessing methodological advancements, and highlighting the broader applications of LCZ classifications. Through this structured analysis, the study underscores the significance of LCZs in shaping urban climate research and their potential for further interdisciplinary applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Scope and Rationale

This study adopts a structured literature review design to ensure methodological transparency, reproducibility, and broad coverage of Local Climate Zone (LCZ) applications in urban climate modeling. The primary objective is to consolidate a decade of scientific progress, tracing the evolution of LCZs from an experimental concept to a widely used methodological framework in urban climatology. Although this review does not follow the full PRISMA protocol, it integrates core elements of systematic review methodology, including explicit search strategies, predefined inclusion criteria, and transparent synthesis procedures, while maintaining the interpretive depth characteristic of semi-systematic reviews. This design was intentionally selected to enable both breadth and analytical depth, allowing for a nuanced synthesis of methodological advancements across diverse modeling systems and research domains that a traditional systematic review, focused on a single narrow research question, might not fully capture.

2.2. Search Strategy and Database Selection

An extensive and reproducible literature search was conducted across five major scientific databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect. The search period spanned from January 2013 to December 2024, corresponding to the decade during which LCZ-based modeling became a prominent methodological approach following the framework’s introduction by Stewart and Oke [

2]. As a preliminary step to the formal search, the specific modeling systems were pre-identified through an initial scoping survey of current research initiatives and the existing body of literature. This survey allowed for the identification of the most frequent numerical frameworks used in conjunction with LCZs, ensuring the selection was representative of the dominant technical pathways in the field. These models were selected because they possess a documented history of community usage in transitioning from default land-use categories to LCZ-based parameterization. This selection covers the full spectrum of urban modeling: mesoscale systems (WRF, COSMO, SURFEX) for regional dynamics, local-scale diagnostic models (MUKLIMO-3, UrbClim) for climatological assessments, and microscale building-resolving models (ENVI-met) for neighborhood design. Including these distinct ‘families’ ensures a comprehensive review that captures the varied technical requirements and implementation strategies across the field.

Boolean search strings were applied to identify relevant publications that combined general and model-specific terminology. For example, a core search query was constructed as: (“Local Climate Zone” OR “LCZ”) AND (“urban climate model” OR “WRF” OR “ENVI-met”) AND (“urban heat island” OR “thermal comfort”).* The full set of terms included “Local Climate Zone,” “LCZ classification,” “urban climate modeling,” “urban canopy model,” “WRF,” “MUKLIMO_3,” “COSMO,” “SURFEX,” “UrbClim,” “ENVI-met,” “SUEWS,” “RayMan,” “CFD,” and “VCWG,” in conjunction with key thematic concepts such as “urban heat island,” “thermal comfort,” “extreme weather,” “urban energy balance,” and “mitigation strategies”. The selection criteria focused on identifying studies that contributed to the methodological advancement and practical implementation of LCZ classifications. These studies were categorized into three maturity stages: (1) testing and measurement, which examining studies that have validated and assessed the accuracy of LCZ-based classifications; (2) operational and planning-oriented applications, involving the implementation of LCZs in real-world scenarios like climate adaptation; and (3) expansions beyond urban climate, highlighting the integration of LCZs into fields such as air pollution modeling, hydrology, and remote sensing.

To ensure a comprehensive overview of the field, we adopted an exhaustive search strategy rather than a selective one. Given that the total volume of literature on this at this specific intersection remains manageable, no exclusion criteria were applied to the identified set. Consequently, all identified papers were included in the final analysis. It is important to note that while the modeling systems were selected using an exhaustive, non-restrictive strategy, the associated literature was subsequently screened using article-level eligibility criteria outlined in

Section 2.3.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria for Literature Inclusion

To ensure the dataset consistency and scientific integrity of the dataset, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were established prior to data collection. Only peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2013 and 2024 and written in English were considered. Studies were included if they explicitly employed LCZ classifications within urban or regional climate modeling frameworks and addressed at least one key urban climate phenomenon, such as the urban heat island, human thermal comfort, air quality, or climate adaptation. Non-peer-reviewed sources, including conference proceedings, theses, and technical reports, were excluded, as were studies that mentioned LCZs but did not integrate them into modeling processes or that focused solely on land-use classification without a climate modeling component. These criteria ensured that only methodologically robust and directly relevant works were incorporated into the review.

2.4. Screening and Selection Process

The literature screening and selection process followed a four-stage protocol designed to enhance reproducibility and methodological transparency. The initial phase involved removing duplicate records across databases. This was followed by title and abstract screening to identify potentially relevant studies. The third phase consisted of full-text evaluation based on the established inclusion criteria, ensuring that only studies demonstrating substantive LCZ integration were retained. The final phase involved an eligibility assessment, during which studies were examined for methodological rigor, clarity of modeling implementation, and relevance to the review’s objectives. While a formal PRISMA flowchart was not used, the process adhered to the same logic of systematic filtering and quality appraisal, thereby ensuring a comprehensive and unbiased dataset.

2.5. Data Extraction and Categorization Framework

All eligible studies were systematically analyzed through a standardized data extraction framework that captured essential bibliographic, methodological, and thematic information. Each study was documented with reference to its authorship, publication year, study area, modeling system, parameterization approach, objectives, and principal findings. To facilitate structured analysis, the collected studies were organized into three thematic domains that reflect the trajectory of LCZ applications in urban climate research. The first domain, termed “testing and measurement,” includes studies that validated and assessed the performance of LCZ-based models using remote sensing, GIS analysis, or in situ data. The second domain, “application,” encompasses studies integrating LCZ classifications into numerical modeling systems such as WRF, MUKLIMO_3, COSMO, SURFEX, ENVI-met, and UrbClim to simulate phenomena including urban heat islands, human thermal comfort, and extreme events. The third domain, “expansion,” highlights studies that extended the use of LCZs beyond urban climatology, for instance into hydrology, air quality modeling, and ecological analysis. This threefold categorization allowed for a coherent synthesis of trends, innovations, and methodological progress across disciplines.

2.6. Methodological Limitations

This review is limited to studies published in peer-reviewed journals and written in English, which may have resulted in the exclusion of relevant research published in other languages or presented in conference proceedings. While this decision ensured methodological consistency and quality assurance, it may also introduce publication and language bias. Furthermore, the exclusion of grey literature and non-peer-reviewed sources was intended to preserve analytical rigor, but it inevitably narrows the breadth of the reviewed evidence base.

Although this review follows a structured and reproducible approach, it does not include a formal quantitative meta-analysis or a statistical assessment of publication bias. The synthesis remains interpretive in nature, focusing on methodological trends and cross-disciplinary linkages rather than statistical effect sizes. Nevertheless, the review provides a transparent, comprehensive, and academically rigorous framework for understanding the evolving role of LCZs in urban climate modeling and offers a reliable foundation for future research seeking to enhance urban climate model performance through standardized morphological classification systems.

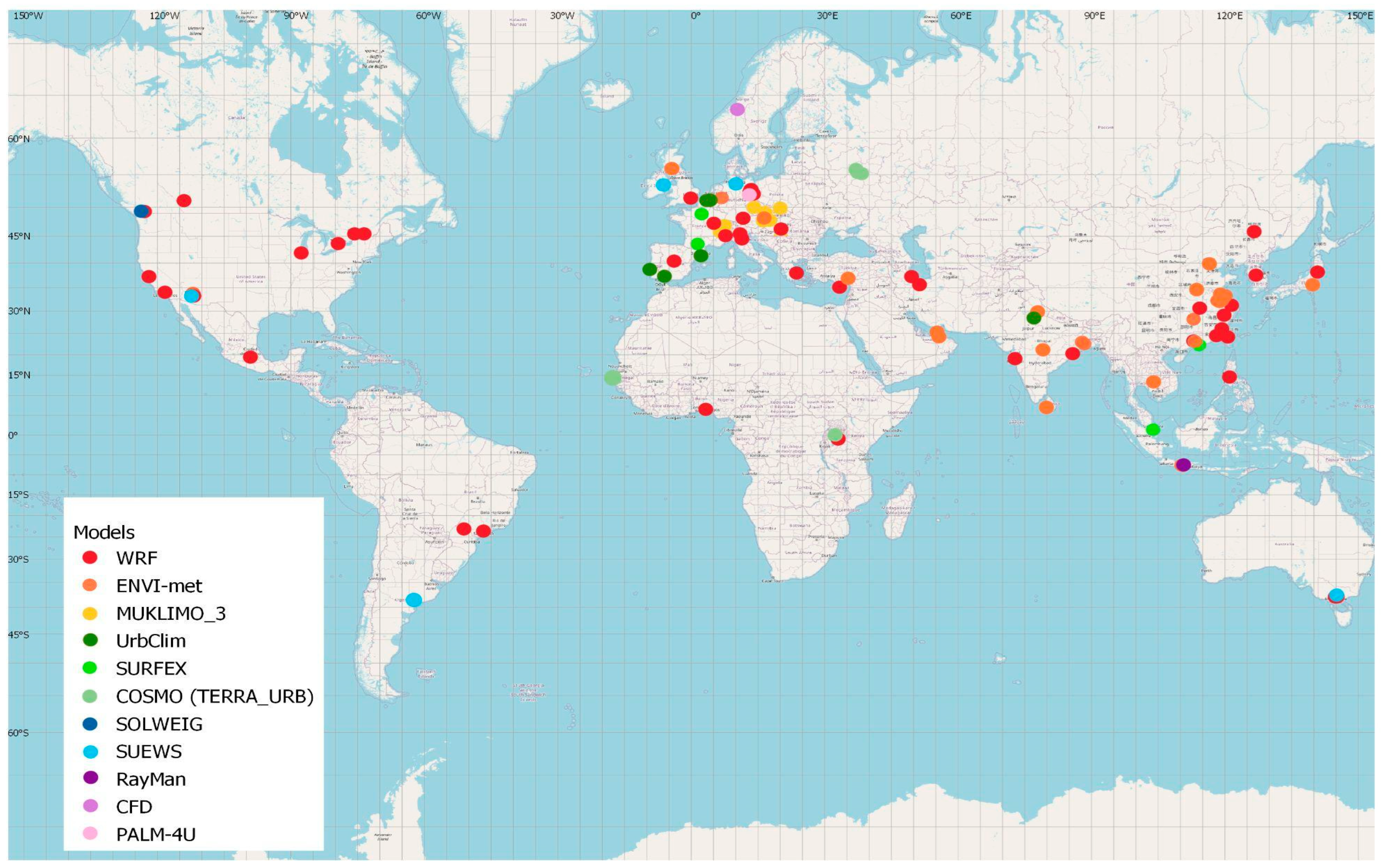

2.7. Geographical Distribution of Studies

The geographical distribution of LCZ-based urban climate studies reveals strong regional patterns in model selection and research emphasis. WRF dominates globally, with dense clusters across East Asia (China, Japan, South Korea), South Asia, and major urban centers in Europe and North America, reflecting its role as the primary mesoscale framework for LCZ integration. ENVI-met studies are concentrated in Europe, the Middle East, South Asia, and parts of China, consistent with its use in micro-scale urban design and thermal comfort assessments. MUKLIMO_3 exhibits a distinctly Central European focus, including Austria, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, aligning with its development and operational use within the DWD community. UrbClim applications cluster in Western Europe (Belgium, Portugal, Spain) and parts of South Asia, reflecting its computational efficiency for UHI assessment. SURFEX and COSMO (TERRA_URB) appear primarily in Western and Central Europe, as well as selected African and Asian cities, indicating their regional adaptation within European research institutions. Supporting models such as SUEWS, SOLWEIG, RayMan, CFD, and PALM-4U appear more sparsely, often linked to targeted microclimate or model-coupling studies in Europe and selected global case locations. Overall, the global evidence map (

Figure 1) depicts the location of the selected peer-reviewed studies using distinct symbols to represent the specific urban climate model employed.

4. Discussion

Across recent literature, LCZ-driven urban climate modeling has evolved into a mature, multiscale ecosystem in which model selection, spatial resolution, computational cost, and research intention must be balanced against one of three major purposes: Category 1 (Testing and Measurement), Category 2 (Application of the model), and Category 3 (Expansion beyond Urban Climate). The LCZ scheme increasingly functions as a shared morphological vocabulary, enabling comparability across cities and improving coherence in cross-scale modeling workflows from regional to microscale.

At the mesoscale, the WRF model family stands out as the most widely adopted LCZ-enabled platform. Its suite of urban canopy schemes (SLUCM, BEP, BEM, and multilayer variants) allows LCZ classes to be translated into detailed urban canopy parameters, improving the representation of spatial heterogeneity in temperature, UHI intensity, surface fluxes, humidity, and urban–boundary layer processes. Early work focused largely on Category 1 validation, such as LCZ-system testing in Madrid, Vienna, Dijon, and Barcelona [

20,

24,

25,

48], or parameter evaluation studies in Hong Kong, Szeged, and Guangzhou [

26,

29,

87]. In recent years, however, the center of gravity has shifted toward Category 2 applied studies, including heatwave diagnostics [

78,

135], UHI adaptation and cool roof evaluation [

35,

50,

77], and blue–green infrastructure analysis [

37,

93]. Selective Category 3 expansions integrate LCZ parameterization into air-quality modeling [

40,

74,

80], greenhouse gas simulations [

82], and building-energy studies [

88]. WRF’s role as a mesoscale driver within multiscale chains (most notably WRF outputs that are downscaled using PALM-4U, and ENVI-met) positions it as the backbone of LCZ-based workflows linking regional-scale forcing with microscale urban processes [

36,

199].

On the other hand, SURFEX/TEB has developed a distinct LCZ pathway through the introduction of ECOCLIMAP-SG [

123], which standardizes the translation of LCZ classes into surface parameters. This harmonization enables consistent multi-city comparisons and strengthens SURFEX’s use in Category 2 applications, including weather forecasting, UHI diagnostics, and thermal-stress analyses [

125,

126,

128]. The model’s compatibility with ALADIN and Meso-NH allows LCZ information to propagate upward into regional dynamics, yielding thermodynamically coherent signals over urban and peri-urban domains. While Category 1 testing does occur (such as LCZ-driven validation exercises in Singapore and Toulouse) the system’s operational orientation makes it an increasingly important tool for scenario evaluation and climate-service applications.

The COSMO model with TERRA_URB occupies an intermediate position in the ecosystem. Although the number of LCZ–COSMO studies is modest, existing work demonstrates clear benefits for nocturnal UHI retention, wind pattern representation, and surface–atmosphere exchanges in cities such as Moscow [

116,

118] and African urban centers [

21,

117]. As a result, COSMO has remained weighted toward Category 1 methodological analyses, but its sensitivity to morphological settings and refined regional throughput suggest growing potential for Category 2 applications, especially as LCZ-based parameter libraries expand.

In the local-scale modeling sphere, MUKLIMO-3 leverages LCZs to produce high-resolution, multidecadal climate indices using the cuboid statistical method [

101,

102]. Most LCZ–MUKLIMO-3 studies fall squarely within Category 2, supporting urban planning, climate-risk assessment, and heat-stress projections in Central European cities such as Bratislava, Brno, Krakow, and Szeged [

103,

104,

105,

108]. A smaller number focus on Category 1 validation, including model observation comparisons in Slovakia and Austria [

106,

111]. Its computational efficiency makes it a valuable tool for long-term, high-resolution scenario screening under future climate conditions.

At the microscale, ENVI-met and CFD-based models deliver the highest spatial fidelity in radiation exchange, comfort metrics, ventilation pathways, and street-canyon dynamics. While these systems do not import LCZ maps directly, LCZ-informed surface archetypes (cover fractions, height distributions, aspect ratios, materials, and vegetation) serve as robust parameter inputs across a large body of Category 2 design-oriented studies [

143,

145,

146]. Their computational demands limit their use in city wide or long-term analyses, reinforcing their role as neighborhood scale diagnostic tools. UrbClim, by contrast, provides a computationally efficient meso-urban alternative: when coupled with LCZ maps, it captures neighborhood-scale thermal contrasts with high realism and is widely used in Category 2 applications, particularly in European and Asian cities [

132,

133,

136,

140].

A set of supporting models extends LCZ applications into additional domains. SUEWS leverages LCZ-dependent land cover fractions to refine energy and water partitioning [

166,

167]. SOLWEIG and RayMan focus on radiation and human energy balance, often used for LCZ-based comfort evaluation and design appraisal [

171]. CFD tools and VCWG provide detailed vertical and micro flow diagnostics, most often in Category 1 and 2, while PALM-4U, though constrained by grid–LCZ resolution mismatches, increasingly appears in WRF-driven multiscale chains, marking an emerging frontier for LCZ integration in building-resolving LES [

36]. The rise of model fusion which is evident in workflows such as WRF with ENVI-met [

199], WRF with PALM-4U [

36], and integrated blue–green infrastructure assessments [

37] is one of the field’s most important methodological advances. LCZs offer a standardized framework for transferring morphology, thermodynamics, and surface parameters across scales, enabling coherent, multilevel analyses that more closely mirror the complexity of real urban systems.

Across all families, two cross-cutting insights emerge. First, LCZ data quality is consistently pivotal: biases in LCZ mapping or parameter assignment propagate through every model class, limiting potential gains from advanced physics or higher resolution. Second, the development of standardized LCZ to UCP translation libraries, refined by climate region and building typology, would greatly enhance model comparability and reproducibility, particularly for multi-city research, climate services, and policy-relevant applications. Overall, the LCZ modeling ecosystem reveals a coherent division of labor. WRF and SURFEX/TEB function as process-rich mesoscale backbones spanning Categories 1 to 3; MUKLIMO-3 and UrbClim deliver efficient, policy-ready outlooks for Category 2; ENVI-met and CFD tools provide high resolution microscale insight; and supporting models extend LCZ usage into hydrology, radiation comfort, and Earth system contexts. The most influential studies treat LCZs not merely as inputs but as an organizing framework for multiscale simulation, aligning directly with the category scheme and the latest body of LCZ-driven urban climate research.

Table 9 provides a summary of model scheme, scale, resolution range, category, and application focus for each LCZ-based model.

Limitations and Future Directions

In addition to the scope-related constraints previously outlined, such as the reliance on English-language, peer-reviewed publications and the interpretive nature of the synthesis, this review is also limited by several methodological and data-driven challenges inherent to current LCZ research. Firstly, existing LCZ datasets exhibit notable geographical and climatic imbalances, largely due to uneven mapping efforts and variations in classification practice. These gaps reduce the global representativeness of LCZ-based studies and underscore the need for more rigorous quality control and inter-operator validation. To address this limitation, future work should prioritize the development of standardized, globally consistent LCZ data quality metrics to ensure greater comparability across studies. As emphasized by Li et al. [

11], future research should focus on developing and validating LCZ datasets in climate-vulnerable regions (e.g., Sub-Saharan Africa, South America) to ensure the framework’s utility is truly global and relevant for climate adaptation policy. This necessary expansion must be paired with the rigorous standardization and quality assurance protocols called for by Han et al. [

10]. Expanding LCZ coverage to include currently underrepresented climate zones will also be critical for improving the robustness and spatial equity of LCZ-based modeling frameworks.

Another major limitation concerns the fidelity of translating categorical LCZ classes into the continuous urban canopy parameters (UCPs) required by numerical models. This translation introduces inherent parameterization uncertainty, as static lookup tables may not fully capture the heterogeneity and dynamic behavior of real urban environments. Such uncertainty represents a methodological bottleneck that can propagate through subsequent modeling steps, influencing the accuracy of thermal, climatic, and energy predictions. In this regard, reducing parameterization uncertainty will require the integration of advanced methods that move beyond static lookup tables. Emerging approaches (such as machine learning, dynamic UCP estimation, and hybrid modeling techniques) offer promising pathways to enhance the accuracy and adaptability of LCZ-to-UCP translation.

While a comparative analysis of model performance and trade-offs (e.g., computational cost versus physical realism) is highly desirable, it remains outside the scope of this study, which focuses primarily on the integration of LCZ land use inputs. A rigorous synthesis of model capabilities requires standardized benchmarking data that is not currently available. Consequently, we propose that a comprehensive inter-model comparison be established as a future research priority, ideally conducted through a multi-institutional collaborative consortium.

5. Conclusions

Over the past decade, the LCZ framework has become a central organizing structure for urban climate modeling, enabling physically consistent, comparable, and interpretable simulations across scales. This review synthesizes that evolution through a three-level maturity lens: Category 1 (Testing and Measurement), Category 2 (Application), and Category 3 (Expansion beyond urban climate), demonstrating how LCZ now underpin workflows ranging from methodological evaluation to policy relevant planning and emerging Earth system integrations. Across all model families, a coherent division of labor has emerged: WRF and SURFEX/TEB provide process-rich mesoscale foundations; MUKLIMO-3 and UrbClim support efficient scenario screening and multi city climatologies; ENVI-met and CFD tools resolve neighborhood-scale morphology and comfort; and supporting models such as SUEWS, SOLWEIG, RayMan, VCWG, and CESM-CLMU extend LCZ usage into hydrological, radiative, and global contexts. Together, these systems illustrate that LCZ are no longer simply data inputs but function as a unifying scaffold allowing diverse urban climate models to interoperate more coherently.

A major insight from the evidence is that model performance is fundamentally limited by surface representation. When LCZ maps or LCZ to UCP translations are noisy or inconsistent, improvements in physical parameterizations offer diminishing returns. Strengthening LCZ data quality through higher spatial resolution, uncertainty characterization, temporal updates, and climate- specific parameter tables, represents one of the most impactful investments for the field. Although models are moving toward hectometric resolutions, the Local Climate Zone (LCZ) scheme remains conceptually robust because the source area for screen-level air temperature in urban environments naturally extends to several hundred meters. Consequently, the LCZ scale accurately captures the aggregated thermal signal relevant to the urban atmosphere, ensuring validity even when the computational grid is finer. Equally important is the development of transparent, community-maintained LCZ to UCP translation workflows, which would substantially enhance reproducibility, portability, and cross city comparability.

The field is also trending toward interoperable model chains, where LCZs ensure consistent hand-offs across scales. Couplings such as WRF and PALM-4U, as well as WRF and ENVI-met illustrate the growing capacity to link synoptic forcing, neighborhood morphology, and street level thermal comfort within a unified modeling pipeline. Formalizing these cross scale integrations with shared metadata, quality controls, and scalable parameter transformation will be essential for the next generation of urban climate services. Bridging LCZ information with LES simulations remains an open but increasingly tractable challenge as higher resolution morphological datasets and adaptive parameterization strategies mature. In practical terms, this review highlights clear guidance for model selection: UrbClim for rapid multi scenario screening, MUKLIMO-3 for multidecadal heat stress assessments, ENVI-met/CFD for design scale ventilation and comfort, and WRF or SURFEX/TEB for city to regional extremes and coupled chemistry or energy studies. These approaches are complementary, and the strongest studies integrate multiple families within LCZ-anchored frameworks.

While this review is limited to peer-reviewed, English language publications and emphasizes interpretive synthesis over meta analysis, the overarching patterns are consistent across cities, climates, and modeling approaches. By consolidating methodological progress and identifying areas where standardization and data quality are most urgently needed, this review provides a pathway toward more credible, comparable, and actionable LCZ-based urban climate intelligence. Ultimately, advancing the field will depend less on creating new models than on improving the LCZ data, translation layers, and inter-model interoperability that allow existing tools to work together effectively in a rapidly changing urban world.