Atmospheric Processes over the Broader Mediterranean Region 1980–2024: Effect of Volcanoes, Solar Activity, NAO, and ENSO

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Part A—Physical Approach

3.1.1. Observed and Estimated Aerosol Optical Depth

3.1.2. Effect of Volcanoes

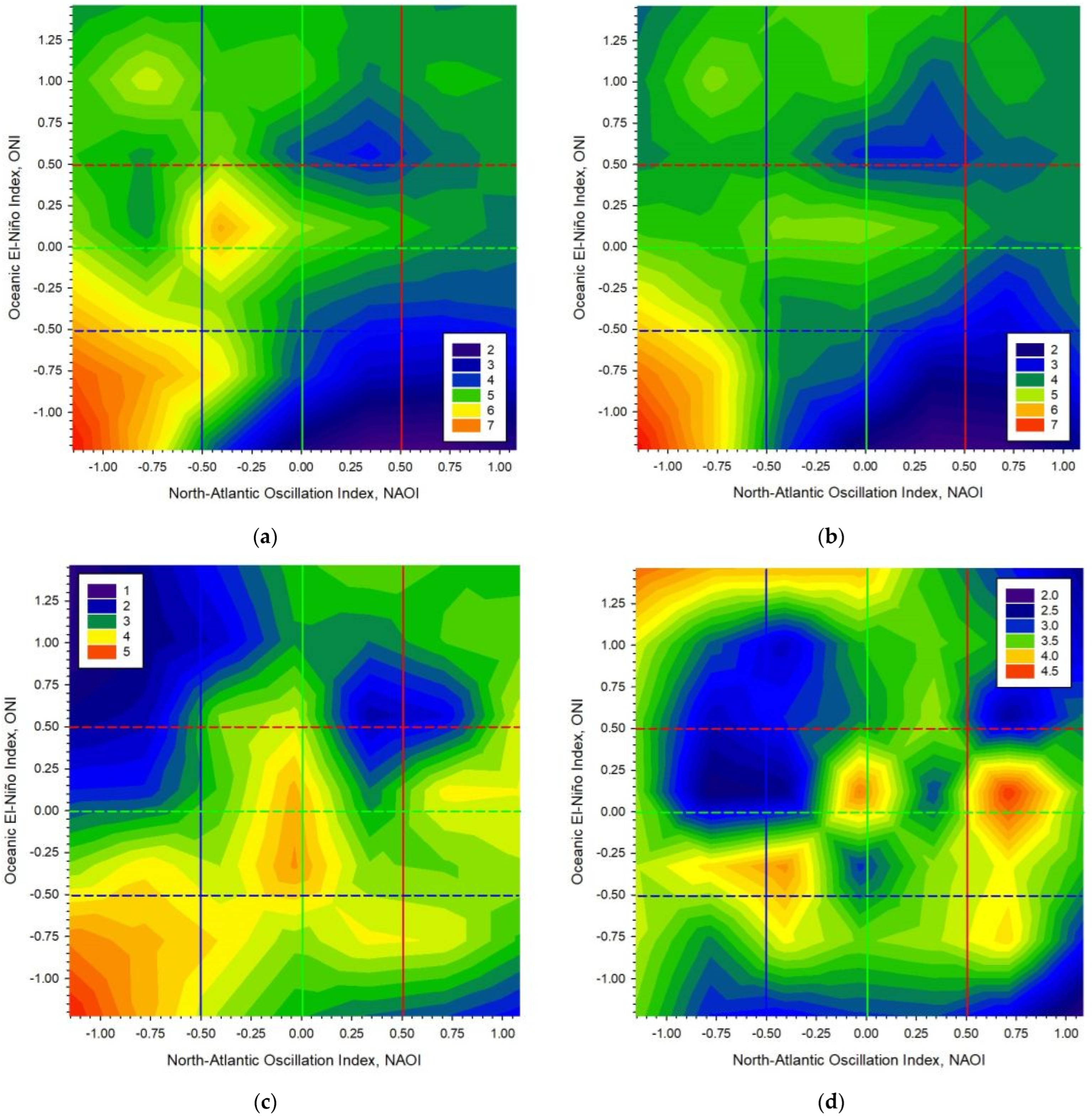

3.1.3. Effect of NAO and ENSO

3.1.4. Effect of Desert Dust and Black Carbon

3.1.5. Examination of Some Individual Aerosol Parameters

- WestMed. The expression TAOD550 = SAOD550 + AAOD550 could alternatively be written as TAOD550 = (DAOD550 + OSAOD550) + AAOD550 (see Equations (8)–(10)). In the event of a Sahara dust outbreak, the scattering particles could include dust particles as well as other particles (such as sea-salt, sulphates, and nitrates, denoted as OSAOD550 in the equation). By replacing the average values of TAOD550 = 0.203, AAOD550 = 0.012, SAOD550 = 0.191, and DDAOD550 = 0.103 in the last expression, it is easily found that the average OSAOD550 is 0.088, which is equal to ≈7·AAOD550. In the same way, DAOD550 ≈ 9·AAOD550. Therefore, TAOD550 = (9·AAOD550 + 7·AAOD550) + AAOD550 = 17·AAOD550. This outcome indicates that the total solar radiation attenuation in the WestMed subregion is 17 times more than the attenuation resulting from aerosol absorption alone.

- CentMed. Following the same procedure, it is estimated that TAOD550 = 19·AAOD550. This implies that the total solar radiation is attenuated in the CentMed subregion 19 times by an atmosphere containing absorbing aerosols only.

- EastMed. Here, TAOD550 = 19·AAOD550, as in CentMed. This result shows the resemblance of the aerosol profiles in these two Mediterranean subregions (cf. Figure 10b,c).

- BalBSea. Now, TAOD550 = 23·AAOD550 having a higher coefficient than the one in the other three subregions (see the aerosol profiles in Figure 10d).

- Kambezidis [31] found the AAOD550 coefficient to be 18 for the whole Mediterranean area in the same period, a value rather close to the average of the four coefficients in the present study (19.5).

- The immediate conclusion from the above results is that the contribution of absorbing aerosols to the total solar radiation attenuation becomes less and less important from WestMed to BalBSea as its role is progressively taken up by the scattering effect. This is also confirmed by the progressively increasing average SSA values over the four subregions: 0.939 (WestMed), 0.947 (CentMed), 0.948 (EastMed), and 0.958 (BalBSea).

3.1.6. General Conclusions from Section 3.1.1 to Section 3.1.5

- Volcanic eruptions, depending on the amount of debris outflown in the atmosphere, can mask and modulate the optical properties of the natural and anthropogenic aerosols. In the present study, volcanoes from the (continuously updating) catalogue of the Global Volcanism Programme, Smithsonian Institute (https://volcano.si.edu), were selected in the period 1980–2024. They are characterised by VEIs in the range 4–6, except for Etna and Stromboli volcanoes in CentMed, that were “allowed” to have VEIs of 2 and 3.

- The ΔTAOD550 values were found to be almost negative (i.e., TAOD550 < TAOD’550) in the inner part of the Mediterranean region (CentMed and EastMed), while ΔTAOD550 varied between negative and positive values over WestMed and BalBSea in the whole period of the study. This indicates the smaller effect of clouds on the CentMed and EastMed areas than the other two subregions.

- In an old study, Dutton et al. [96] examined TAOD500 at the Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO, 19.54° N) and found that the maximum values of the parameter were 0.28 and 0.23 from the El Chichón (1982) and Pinatubo (1991) eruptions, respectively. These values are comparable with the peaked values in Figure 2a–d of the present study. Indeed, the maximum annual TAOD550 values for the El Chichón and Pinatubo eruptions are 0.289 and 0.319 (WestMed), 0.319 and 0.335 (CentMed), 0.274 and 0.303 (EastMed), and 0.354 and 0.354 (BalBSea), respectively. These higher maximum values are due to the fact that the MLO is located on the remote island of Hawaii, thus recording the background aerosol loading in the atmosphere. Similar observations to those at the MLO were made at some Antarctic stations by Herber et al. [97]. Sato et al. [80], in a study to investigate the stratospheric aerosol loading from volcanic eruptions in the period 1850–1990, found that El Chichón mostly affected regions in the northern hemisphere at latitudes 0° N–30° N just after its eruption in March/April 1982, and regions at latitudes 60° N–90° N at the end of the year; one can remark that these low-latitude areas in the northern hemisphere include most of the broader region of the Mediterranean in this study, which were affected by those eruptions (see Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 11b and Figure 13a). A similar study by Long and Stowe [98] about the Pinatubo eruption found that the stratospheric aerosol loading was particularly high over areas with latitudes 20° S–20° N just after its eruption in June 1991. This confirms the lower TAOD550 values recorded at MLO due to the Pinatubo eruption in comparison to those over the four Mediterranean subregions (see Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 11b and Figure 13a). A recent work by Toohey and Sigl [99] reconstructed StAODs in the period from 500 BC to 1900 AD; they found peak StAOD550 values ranging between 0.2 and 0.4, quite comparable to the two peaks shown in Figure 2 in the four Mediterranean subregions due to the El Chichón and Pinatubo eruptions.

- For the first time, it was demonstrated that the TAOD550,WVE time series, i.e., atmospheric aerosols devoid of volcanic materials but including anthropocentric-origin ones, show rather constant levels (no significant trend) in any of the four Mediterranean subregions. This outcome indicates that a volcanic-debris-free atmosphere may have a lesser impact on the climate change phenomenon. Such a simulation has never been attempted to the knowledge of the author, and it would be interesting to examine the characteristics and evolution of a volcanic-debris-free climate in the past and the future.

- The desert-dust and black-carbon aerosols themselves account for half of the aerosol loading in the broader area of the Mediterranean region, especially over the Mediterranean Sea and the surrounding countries; an exception is the Balkans and Black Sea areas where the contribution from desert dust has a lesser or negligible effect.

- The majority of the annual TAOD550 values are favoured by negative and neutral ENSO conditions (see Figure 8).

- The linear regression fits to TAOD550 as a function of time (see Figure 3) give the following trends: −0.017/decade (WestMed); −0.024/decade (CentMed); −0.013/decade (EastMed); and −0.037/decade (BalBSea). All trends are negative with a greater slope over BalBSea and a smaller slope over EastMed. Kambezidis [31] found a trend over the entire Mediterranean in the period 1980–2022 equal to −0.018/decade, close to the average of the above four TAOD550 slopes (−0.023/decade). Chiapello et al. [86] found a TAOD550 trend of −0.06/decade over the Western Mediterranean in the period 2005–2013, which is almost three times higher than the corresponding average value in the present work. Shaheen et al. [60] found a TAOD550 trend over EastMed of ≈−0.002/decade from MERRA-2 in the period 1980–2018, ten times lower than the average value in the present work. These varying slopes among different studies are due to the different periods examined, the source of the data used, and the areas covered; they, therefore, reflect the need to standardise the whole procedure for a more comparable way among various works.

- The linear regression fits to TAOD550,WVE as a function of time (see Figure 5) derived the following trends: +0.003/decade (WestMed); +0.003/decade (CentMed); +0.006/decade (EastMed); and +0.002/decade (BalBSea). These trends are all positive, greater in EastMed, smaller over BalBSea, equal in the other two areas, and an order of magnitude lower than those for TAOD550.

- The above result shows that the atmospheric aerosol loading over the entire Mediterranean in the period 1980–2024 has a negligible trend or is rather constant in the absence of global volcanic eruptions.

- There is an almost 50%/50% balance between the desert-dust/black-carbon aerosols and the stratospheric/sea-salt/cloud effect on the total aerosol loading over the WestMed, CentMed, and EastMed areas (see Figure 9). The BalBSea subregion is affected more by black-carbon aerosols than volcanic eruptions, probably because of its remote location.

- To include the cloud effect as a component of SAOD550, the COD values can be divided by 1000 in order to derive comparable values with SAOD550 (see Equation (9)).

- TAOD550 was found as a function of AAOD550 over the four areas: TAOD550 ≈ 17·AAOD550 (WestMed), TAOD550 ≈ 19·AAOD550 (CentMed, EastMed), and TAOD550 ≈ 23·AAOD550 (BalBSea). The higher weighting factor for BalBSea (i.e., 23) refers to the higher contribution of absorbing aerosols to the total aerosol loading over the region in comparison to that over the other three areas. This was justified in Figure 10 and Figure 12.

- Regardless of the ENSO phase, all AE470–870 values indicate coarse-mode particles across the Mediterranean on a yearly basis. Fine-mode aerosols are linked to only two years: 1983 and 1992, related to the volcanic eruptions of Mt. El Chichón and Mt. Pinatubo, respectively.

- Most of the aerosol types fall into the MTA and UIA categories over the entire Mediterranean region. There is an absence of or at least a contribution to desert-dust aerosols over BalBSea.

3.2. Part B—Statistical Approach

3.2.1. Nexus Between the Aerosol Parameters and SSN/NAOI/ONI

3.2.2. Nexus Between the Aerosol Parameters and the Four Mediterranean Areas

- BalBSea. Correctly classified: 21%; often misclassified as CentMed (6%) and EastMed (7%); suggests overlap in aerosol signatures with neighbouring subregions.

- CentMed. Correctly classified: 7%; frequently confused with EastMed (1%) and WestMed (4%); indicates transitional aerosol behaviour.

- EastMed. Correctly classified: 9%; misclassified as BalBSea (1%) and WestMed (3%); suggests shared fine-particle regimes.

- WestMed. Highest correct rate: 12%; still confused with EastMed (6%) and CentMed (6%); likely reflects seasonal dust variability.

3.2.3. Descriptive Statistics

- The magnitudes of the μ, σ, and m values for the parameters of TAOD550, AAOD550, SAOD550, SSAOD550, BCAOD550, and SSA are similar throughout the four Mediterranean subregions. This suggests that the subregions have comparable aerosol loading patterns. The significance of large water bodies (Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea) must be acknowledged here, particularly for the SSAOD550 and BCAOD550 parameters, as these aquatic surfaces contribute to TAOD550 with relatively high sea-salt aerosol loads. On the other hand, numerous large cities, industrial areas, and wildfires around the Mediterranean contribute to TAOD550 with black-carbon aerosols, particularly over BalBSea (see µ in Table 5).

- In contrast, the DDAOD550, StAOD550, and AE470–870 parameters exhibit a declining, rising, and increasing trend, respectively, from WestMed to BalBSea. This suggests that the overall particle sizes of the aerosols of volcanic debris and desert dust vary across the four Mediterranean subregions. While stratospheric aerosols appear to finally influence the Balkan peninsula and Black Sea area more (see Figure 4 and µ in Table 5), desert-dust outbreaks from the Sahara Desert dominate the West Mediterranean [100]. According to AE470–870, fine-mode aerosols gradually take over from WestMed to BalBSea (see Figure 10a and µ’s in Table 5).

- As DARF decreases from WestMed to BalBSea, a comparatively greater warming effect was observed over the West Mediterranean than over the Balkans and Black Sea regions (see µ’s in Table 5). In contrast, COD is marginally rising in each of the subregions listed, which is consistent with [31], who noted it for the Mediterranean region as a whole. However, between 1979 and 2012, Kambezidis et al. [101] discovered rising trends in COD for mid- and high- level clouds and falling trends for low-level clouds. A modest increasing trend in COD was observed from WestMed to BalBSea (see COD μ’s in Table 5), taking into account all clouds in the current study. This discovery is consistent with the increasing COD in [101] and could be explained by the fact that MERRA-2 reanalysis data “see better” upper clouds.

- Table 5’s average yearly COD values are in line with those from other studies. For instance, in the Atacama Desert in Northern Chile, Luccini et al. [102] discovered COD levels of about 15 (at Arica) and about 11 (near Poconchile). It is important to keep in mind that the COD values indicate how frequently cloudiness occurs in a given area; they are lower in deserts and greater in the Mediterranean regions that include vegetation and water surfaces.

- For the majority of parameters (except from DDAOD550 and COD in all four areas and for AAOD550 and DARF over BalBSea), linear regression fits to the data points of the parameters as a function of time, t (years in the period 1980–2024), demonstrated significance at the 99.9%, or 95% CI. One can, therefore, forecast the parameter level shortly after 2024 with a reasonable degree of accuracy thanks to the high CIs (the accuracy assumes no additional high volcanic activity at the global level). For instance, according to the Giovanni platform (accessed on 27 January 2025), the μTAOD550 values for January 2025 for the four locations are 0.087, 0.118, 0.105, and 0.098, respectively. The January 2025 values, also calculated using the linear regression formulas (not displayed here for spacing reasons), were found to be 0.070, 0.100, 0.115, and 0.098, respectively, quite close to the observed (Giovanni) ones.

- Except for the DARF and COD parameters, which displayed positive trends (see α’s in Table 5), all of the aerosol and atmospheric metrics have trends that are marginally negative or even close to zero.

- The four Mediterranean subregions’ average yearly AE470–870 values for the study period were determined. For the entire Mediterranean, Kambezidis [31] obtained an average AE470–870 value of 0.939, which is very similar to the average of the four subregions (0.989). However, Ozdemir et al. [85] observed higher AE470–870 values for the East Mediterranean between 1999 and 2018, in the range 1.15–1.66. From 2000 to 2015, Sharafa et al. [100] discovered that the average annual AE470–870 values from AERONET stations in three sub-Saharan African nations ranged from 0.555 to 1.722. AE440–870 fluctuated between 0.92 and 1.57 over the Mediterranean between 1996 and 2012, according to Mallet et al. [88]. These values are in line with the 0.874–1.217 values obtained in the current investigation.

3.2.4. Deseasonalisation; Stationarity; Cross-Correlation Analysis; Durbin–Watson Test; Granger-Causality Test

- Stationarity. It is necessary for the time series to be stationary, meaning that its statistical characteristics, such as μ and σ, must remain constant over time. Numerous statistical tests can be used to analyse stationarity. The present study decided to use the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test [105]. The Ho hypothesis makes the assumption that the time series are stationary during the test. The time series are said to be stationary if the corresponding p-values are less than or equal to α (0.05 for 95% CI or 0.01 for 99% CI), which means that Ho applies. The stationarity results for all variables examined for the four Mediterranean subregions between 1980 and 2024 are displayed in Table A4 (see Appendix A). Before moving on to the GC application, the deaseasonalised time series in Table A5 that were determined to be non-stationary received a first-order difference statistical modification to become stationary (see Table A6, Appendix A).

- Linearity. There are several statistical measures available to assess whether the independent and dependent time series are linear. The rather low R2 values indicate a weak linearity between the paired parameters, although this does not exclude the use of the GC statistic. In this case, the R2 values were adopted in the regression analysis between SSN/NAOI/ONI and an aerosol/atmospheric variable given in Table A3.

- Lag length. In the GC analysis, it is essential to select a suitable lag length for the dependent aerosol/atmospheric variables with respect to the independent variables of SSN/NAOI/ONI time series. Six (months) was determined to be the ideal lag period for the independent variables under investigation. This was accomplished by computing the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC); it was discovered that both BIC and AIC values became stabilised following lag 6. The (ideal) lag 6 in Table A4 further supports this.

- No omitted variables. The results may be skewed if important (independent) variables are left out of the analysis; therefore, all pertinent variables should be included. For this reason, all (independent) SSN/NAOI/ONI time series were used in this study with a lag of six months.

- No multi-collinearity. The independent variables should not be perfectly multi-collinear; high correlation coefficients (around +1 or −1) suggest that multi-collinearity may exist. However, the low (near-to-zero) r values among the SSN/NAOI/ONI time series in Table A3 (Appendix A) indicate that there is no such collinearity for them.

- No auto-correlation of the error terms. Any dependent or independent variable was subjected to a regression analysis against time; the auto-correlation plot of the residuals from each fit revealed no discernible trend. Consequently, no auto-correlation was discovered. By using the Durbin–Watson (DW) test on the regression residuals, the same conclusion was reached: all DW values fell between 1 and 2, suggesting that there was little to no auto-correlation in the residuals. It should be noted that DW values range from 0 to 4, and an auto-correlation is minimal or non-existent when the DW value falls between 1.5 and 2.5.

- Acceptable regression results in the form q = f(SSN,NAOI,ONI) occur for TAOD550, AAOD550 (all domains except ONI in BalBSea), SAOD550 (all domains), DDAOD550, (WestMed, CentMed), StAOD550 (WestMed, BalBSea), SSAOD550 (CentMed, EastMed except NAOI), SSA (BalBSea), DARF (all domains except ONI in BalBSea), netSWRBOA,CS,A, netLWRBOA,CS,A (all domains except ONI in WestMed), and COD (all domains).

- Solar activity (through SSN) does not show a cause–effect on (i) SSAOD550, BCAOD550, AE470–870, and SSA over WestMed; (ii) StAOD550, BCAOD550, AE470–870, and SSA over CentMed; (iii) DDAOD550, StAOD550, BCAOD550, AE470–870, and SSA over EastMed; and (iv) DDAOD550, SSAOD550, BCAOD550, AE470–870, and COD over BalBSea.

- From the above statement, it is obvious that solar activity does not possess a statistically significant cause–effect on BCAOD550 and AE470–870 over the entire Mediterranean region.

- The North Atlantic Oscillation (through NAOI) shows a cause–effect on almost the same parameters and Mediterranean areas with those of SSN.

- The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (through ONI) influences all aerosol parameters mentioned above.

- From Table A7, the SSN/NAOI/ONI time series in the regression analyses include a prevailing retarded six-month influence on the Mediterranean atmosphere. This is almost ½ of the 11-year solar activity cycle and exactly half a full year. In the latter case, one may consider a warm and a cold season of six months duration each; perhaps this occurs because nature favours these two main seasons.

- In the analyses for the cause–effect of the SSN/NAOI/ONI time series on the aerosol/atmospheric parameters in Table A7, only the expressions with overall α ≥ 0.4 (a 60% CI) are shown. Nevertheless, the regression expressions with α < 0.4 still contain certain lagged values of the independent variables.

- The last observation comes in agreement with the initial outcome of a rather synchronous fluctuation in DARF and SSN (see periods 1988–1992 and 1998–2004 in Figure 9 of [31]), and of DARF and ONI (see marked rectangles in Figure A3 of [31]). The characterisation “synchronous” was given by Kambezidis [31], who used annual mean values to show an almost synchronous temporal evolution of the DARF/SSN and DARF/ONI time series. To demonstrate this synchronous fluctuation in ONI and DARF over the four Mediterranean subregions in the case of progressively decreasing positive ENSO phases or turning from positive to negative events, Figure 14 was prepared. The ellipses show the above-mentioned events; the red arrows inside the ellipses indicate the effect of a decreasing ENSO phase on DARF, while DARF follows a similar decreasing tendency with that for ENSO with a retardation of about six months, according to the Granger-causality effect shown in this section. It is, therefore, clearly seen that there exists a signalling effect of the ENSO phase on the DARF levels over all four Mediterranean areas.

3.2.5. Normal Distribution of the Examined Variables

4. Conclusions and Discussion

- Part A. Physical approach

- Part B. Statistical approach

- Are the effects of solar activity, NAO, and ENSO on the atmospheric processes found in [31] valid in smaller areas of the Mediterranean too? The answer to this question is positive. Table A2 and Table A3 (see Appendix A) provide sufficient correlations (positive or negative) at high CIs over almost all four Mediterranean domains considered.

- How do volcanic eruptions affect the status of atmospheric aerosols over the Mediterranean? Extensive analysis provided in Section 3.1.2 showed that the absence of volcanic activity on Earth would result in rather constant levels of the atmospheric processes over all four Mediterranean domains.

- A third significant conclusion related to the first research question was that El Niňo–Southern Oscillation, North Atlantic Oscillation, and solar activity all have an impact on the atmospheric processes over the larger Mediterranean region, either separately or in combination, and this effect can last up to six months. The three events have a weak but significant cause-and-effect relationship that drives several aerosol characteristics, even at a 99.9% significance level.

- Global volcanism.

- Look closely at how global volcanism affects the characteristics of aerosols in regions other than the Mediterranean.

- In the absence of volcanic eruptions, study again the Earth’s climate. Forecast the future and model the past and present world climates devoid of volcanic debris. Since the current study at least showed that large volcanoes have an impact on global aerosol levels and their concentrations as well as on the climate, and that they should not be ignored, there should be alternatives to the “as was in the past” scenario for the years 2015–2100 in light of the IPCC’s upcoming AR7. Thus, the following volcanic scenarios should be considered: (i) unchanged; (ii) absence of dramatic volcanoes; (iii) presence of drastic volcanoes by including extreme volcanism of VEIs of 5 or more (cataclysmic category). Furthermore, these scenarios could potentially be broken down and examined into smaller timeframes within the future timeframe of 2015–2100.

- TAOD550 levels.

- In BalBSea, they are higher for ONI < 0 than for ONI > 0 compared to the other three Mediterranean domains. Then, examine whether this phenomenon holds true for other bordering regions worldwide.

- Examine why they prefer to occur during neutral ENSO phases.

- ENSO, NAO effects.

- Examine how ENSO regulates the circulation of atmospheric aerosols outside of the Mediterranean region.

- Examine how solar activity, NAO, and ENSO affect atmospheric processes in various regions of the planet.

- Examine why black-carbon aerosols have a greater impact over BalBSea than volcanic debris. The sporadic occurrence of the latter type of aerosols across the area could be one factor.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Energetic Volcanoes

| Year | Volcano, Country | VEI |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | St. Helens, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 5 2 2 |

| 1981 | Pagan, USA Alaid, Russia St. Helens, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 5 2 2 |

| 1982 | Galunggung, Indonesia El Chichón, Mexico Pagan, Mexico St. Helens, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 5 4 5 2 2 |

| 1983 | Colo, Indonesia Galunggung, Indonesia Pagan, USA St. Helens, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 4 5 2 2 |

| 1984 | Pagan, USA St. Helens, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 5 2 2 |

| 1985 | Pagan, USA St. Helens, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 5 2 2 |

| 1986 | Chikurachki, Russia Klyuchevskoy, Russia St. Helens, USA Augustine, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 5 4 2 2 |

| 1987 | Klyuchevskoy, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 2 2 |

| 1988 | Klyuchevskoy, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 2 2 |

| 1989 | Klyuchevskoy, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 2 2 |

| 1990 | Kelud, Indonesia Klyuchevskoy, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 2 2 |

| 1991 | Cerro Hudson, Chile Pinatubo, Philippines Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 5 6 2 2 |

| 1992 | Spurr, USA Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 2 2 |

| 1993 | Lascar, Chile Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 1 2 |

| 1994 | Rabaul, Papua N. Guinea Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 3 2 |

| 1995 | Rabaul, Papua N. Guinea Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 3 2 |

| 1996 | Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 3 2 |

| 1997 | Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 3 2 |

| 1998 | Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 3 2 |

| 1999 | Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 3 2 |

| 2000 | Ulawun, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 3 2 |

| 2001 | Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 3 2 |

| 2002 | Reventador, Ecuador Ruang, Indonesia Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 |

| 2003 | Reventador, Ecuador Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 |

| 2004 | Manam, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 |

| 2005 | Manam, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 |

| 2006 | Rabaul, Papua N. Guinea Manam, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 |

| 2007 | Rabaul, Papua N. Guinea Manam, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 |

| 2008 | Kasatochi, USA Okmok, USA Chaiten, Chile Rabaul, Papua N. Guinea Manam, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 4 4 4 |

| 2009 | Sarychev Peak, Russia Chaiten, Chile Rabaul, Papua N. Guinea Manam, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 4 4 |

| 2010 | Merapi, Indonesia Eyjafjallajokull, Iceland Chaite, Chile Rabaul, Papua N. Guinea Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 4 4 |

| 2011 | Nabro, Eritrea Puyehue-Cordon Caulle, Chile Grimsvotn, Iceland Chaite, Chile Sheveluch, Russia | 4 5 4 4 4 |

| 2012 | Nabro, Eritrea Puyehue-Cordon Caulle, Chile Sheveluch, Russia | 4 5 4 |

| 2013 | Sinabung, Indonesia Etna, Italy Sheveluch, Russia Stromboli, Italy | 4 3 4 2 |

| 2014 | Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Kelud, Indonesia Sinabung, Indonesia Etna, Italy Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 4 3 4 |

| 2015 | Wolf, Ecuador Calbuco, Chile Manam, Chile Semeru, Indonesia Sinabung, Indonesia Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy | 4 4 4 4 4 4 3 |

| 2016 | Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Sinabung, Indonesia Etna, Italy Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 3 4 |

| 2017 | Semeru, Indonesia Manam, Papua N. Guinea Sinabung, Indonesia Etna, Italy Sheveluch, Russia | 4 4 4 3 4 |

| 2018 | Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Sinabung, Indonesia Etna, Italy Sheveluch, Russia Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 4 3 4 2 |

| 2019 | Ulawun, Papua N. Guinea Sinabung, Indonesia Manam, Papua N. Guinea Etna, Italy Semeru, Indonesia Sheveluch, Russia Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 4 3 4 4 2 |

| 2020 | Soufriere, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Taal, Philippines Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Etna, Italy Sheveluch, Russia Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 4 4 3 4 2 |

| 2021 | Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, Tonga Fukutu-Oka-no-Ba, Japan Soufriere, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 5 4 4 4 4 4 3 2 |

| 2022 | Hung Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, Tonga Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 5 4 4 4 3 2 |

| 2023 | Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 4 2 2 |

| 2024 | Manam, Papua N. Guinea Semeru, Indonesia Sheveluch, Russia Etna, Italy Stromboli, Italy | 4 4 4 2 2 |

Appendix A.2. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient

| Parameter | Pair of Mediterranean Areas | r |

|---|---|---|

| AE470–870 | WestMed, CentMed | 0.777 |

| WestMed, EastMed | 0.706 | |

| WestMed, BalBSea | 0.678 | |

| CentMed, EastMed | 0.935 | |

| CentMed, BalBSea | 0.895 | |

| EastMed, BalBSea | 0.932 | |

| WestMed, allMed | 0.887 | |

| CentMed, allMed | 0.968 | |

| EastMed, allMed | 0.944 | |

| BalBSea, allMed | 0.895 | |

| DARF | WestMed, CentMed | 0.899 |

| WestMed, EastMed | 0.797 | |

| WestMed, BalBSea | 0.871 | |

| CentMed, EastMed | 0.932 | |

| CentMed, BalBSea | 0.920 | |

| EastMed, BalBSea | 0.913 | |

| WestMed, allMed | 0.950 | |

| CentMed, allMed | 0.983 | |

| EastMed, allMed | 0.938 | |

| BalBSea, allMed | 0.939 |

| Parameters in Pair | r | R2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WestMed | CentMed | EastMed | BalBSea | WestMed | CentMed | EastMed | BalBSea | |

| NAOI-ONI | +0.011 | 0.000 | ||||||

| NAOI-SSN | +0.061 | 0.004 | ||||||

| ONI-SSN | +0.018 | 0.000 | ||||||

| TAOD550-NAOI | −0.059 | −0.017 | +0.205 | +0.231 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.053 |

| TAOD550-ONI | +0.084 | +0.090 * | +0.201 | +0.193 | 0.007 | 0.008 * | 0.040 | 0.037 |

| TAOD550-SSN | +0.173 *** | +0.206 *** | +0.293 | +0.368 * | 0.030 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.086 | 0.135 * |

| AAOD550-NAOI | −0.152 *** | −0.146 *** | −0.285 | −0.031 | 0.023 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.082 | 0.001 |

| AAOD550-ONI | −0.053 | −0.072 | −0.306 * | −0.122 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.093 * | 0.015 |

| AAOD550-SSN | +0.019 | +0.013 | −0.224 | +0.106 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.011 |

| SAOD550-NAOI | −0.052 | −0.009 | −0.215 | +0.232 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.046 | 0.054 |

| SAOD550-ONI | +0.092 * | +0.098 * | +0.211 | +0.195 | 0.008 * | 0.010 * | 0.045 | 0.038 |

| SAOD550-SSN | +0.181 *** | +0.215 *** | +0.299 * | +0.367 * | 0.033 *** | 0.046 *** | 0.089 * | 0.135 * |

| DDAOD550-NAOI | −0.144 *** | −0.108 * | −0.284 | −0.191 | 0.021 *** | 0.012 * | 0.081 | 0.037 |

| DDAOD550-ONI | −0.059 | −0.098 * | −0.284 * | −0.333 * | 0.004 | 0.010 * | 0.110 * | 0.111 * |

| DDAOD550-SSN | +0.052 | +0.014 | −0.011 | −0.043 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| StAOD550-NAOI | +0.101 * | +0.121 * | +0.295 * | +0.231 | 0.10 * | 0.015 * | 0.087 * | 0.053 |

| StAOD550-ONI | +0.225 *** | +0.183 *** | +0.295 * | +0.213 | 0.051 *** | 0.034 *** | 0.087 * | 0.046 |

| StAOD550-SSN | +0.260 *** | +0.236 *** | +0.323 * | +0.353 * | 0.068 *** | 0.056 *** | 0.104 * | 0.124 * |

| BCAOD550-NAOI | −0.108 * | −0.117 * | −0.188 | +0.026 | 0.012 * | 0.014 * | 0.035 | 0.001 |

| BCAOD550-ONI | −0.034 | −0.025 | −0.144 | +0.021 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.000 |

| BCAOD550-SSN | −0.110 * | −0.057 | −0.271 | +0.115 | 0.012 * | 0.003 | 0.073 | 0.013 |

| SSAOD550-NAOI | −0.107 * | −0.061 | −0.212 | −0.278 | 0.012 * | 0.004 | 0.045 | 0.077 |

| SSAOD550-ONI | −0.074 | +0.081 | −0.082 | −0.133 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.018 |

| SSAOD550-SSN | −0.165 *** | +0.126 * | −0.306 * | −0.401 * | 0.027 *** | 0.016 * | 0.093 * | 0.160 * |

| AE470–870-NAOI | +0.197 *** | +0.160 *** | +0.324 * | +0.314 * | 0.039 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.105 * | 0.098 * |

| AE470–870-ONI | +0.219 *** | +0.233 *** | +0.331 * | +0.279 | 0.048 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.109 * | 0.078 |

| AE470–870-SSN | +0.131 * | +0.167 *** | +0.268 | +0.292 | 0.017 * | 0.028 *** | 0.072 | 0.085 |

| SSA-NAOI | +0.152 *** | +0.213 *** | +0.301 * | +0.202 | 0.023 *** | 0.045 *** | 0.090 * | 0.041 |

| SSA-ONI | +0.182 *** | +0.186 *** | +0.287 | +0.210 | 0.033 *** | 0.035 *** | 0.082 | 0.044 |

| SSA-SSN | +0.246 *** | +0.239 *** | +0.306 * | +0.293 | 0.060 *** | 0.057 *** | 0.094 * | 0.086 |

| DARF-NAOI | −0.161 *** | −0.150 *** | −0.294 * | −0.025 | 0.026 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.086 * | 0.001 |

| DARF-ONI | −0.023 | −0.037 | −0.334 * | −0.183 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.111 * | 0.034 |

| DARF-SSN | +0.016 | +0.012 | −0.228 | +0.081 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.007 |

| netSWRBOA,CS,A-NAOI | −0.194 *** | −0.195 *** | −0.027 | −0.046 | 0.138 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| netSWRBOA,CS,A-ONI | −0.013 | +0.013 | −0.098 | −0.143 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.020 |

| netSWRBOA,CS,A-SSN | +0.019 | +0.018 | −0.088 | −0.272 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.074 |

| netLWRBOA,CS,A-NAOI | +0.145 *** | −0.183 *** | −0.154 | −0.266 | 0.021 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.024 | 0.071 |

| netLWRBOA,CS,A-ONI | +0.031 | +0.069 | +0.106 | +0.074 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.005 |

| netLWRBOA,CS,A-SSN | −0.064 | +0.013 | −0.237 | −0.156 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.056 | 0.004 |

| COD-NAOI | +0.076 | +0.235 *** | −0.042 | −0.316 * | 0.006 | 0.055 *** | 0.002 | 0.100 * |

| COD-ONI | −0.023 | −0.030 | +0.200 | +0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.040 | 0.000 |

| COD-SSN | −0.080 | −0.072 | −0.113 | −0.083 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.007 |

Appendix A.3. Time Series Stationarity

| Parameter, q | WestMed | CentMed | EastMed | BalBSea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAOI | 0.2327, 0.1148, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | |||

| ONI | 0.1073, 0.0507, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | |||

| SSN | 1.2061, 0.1620, 6, level/trend non-stationarity at 99%/96.3% CI (needs deseasonalisation) | |||

| TAOD550 | 1.4767, 0.0558, 6, trend stationarity at 90% CI | 2.196, 0.1359, 6, trend stationarity at 93.1% CI | 1.4006, 0.1408, 6, trend stationarity at 94% CI | 4.8332, 0.4187, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) |

| AAOD550 | 0.3933, 0.0480, 6, level/trend stationarity at 92%/90% CI | 0.4635, 0.0556, 6, level/trend stationarity at 95%/90% CI | 1.2862, 0.1582, 6, (needs deseasonalisation) | 0.2097, 0.2160, 6, level stationarity at 99% CI |

| SAOD550 | 1.6464, 0.0628, 6, trend stationarity at 90% CI | 2.6988, 0.1472, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 1.5666, 0.1461, 6, trend stationarity at 95% CI | 4.9290, 0.4260, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) |

| DDAOD550 | 0.0895, 0.0780, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.1610, 0.0790, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/93.4% CI | 0.2178, 0.0669, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.1313, 0.1017, 6, level stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| StAOD550 | 2.9796, 0.1888, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 3.9768, 0.1826, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 2.7110, 0.2011, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 5.5435, 0.5583, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) |

| SSAOD550 | 3.8573, 0.2145, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 1.6125, 0.4173, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 3.6875, 0.0992, 6, trend stationarity at 90% CI | 3.8994, 0.1983, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) |

| BCAOD550 | 3.8221, 0.1895, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 2.5526, 0.3679, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 5.4606, 0.2255, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 0.4781, 0.4447, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) |

| AE470–870 | 2.4305, 0.3405, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 2.5526, 0.3679, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 2.6150, 0.2978, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 3.6170, 0.4681, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) |

| SSA | 5.2424, 0.3160, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 5.2485, 0.3705, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 4.5733, 0.3567, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 5.8728, 0.3991, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) |

| DARF | 0.2874, 0.0318, 6, level/trend non-stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.2355, 0.0266, 6, trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.9382, 0.0671, 6, trend stationarity at 99%/99% CI | 0.1046, 0.0553, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| netSWRBOA,CS,A | 0.0037, 0.0037, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0040, 0.0038, 6, trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0014, 0.0037, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0071, 0.0040, 6, level/trend stationarity 90%/90% CI |

| netLWRBOA,CS,A | 0.1023, 0.0138, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.3624, 0.0520, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90.7%/90% CI | 2.4677, 0.0491, 6, trend stationarity at 90% CI | 1.5676, 0.0808, 6, trend stationarity at 90% CI |

| COD | 0.0935, 0.0832, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0905, 0.0879, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0460, 0.0341, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.1542, 0.1033, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

Appendix A.4. Time Series Stationarity After Deseasonalisation

| Parameter, q | WestMed | CentMed | EastMed | BalBSea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSN | 1.2061, 0.1620, 6, level/trend non-stationarity at 99%/96.3% CI (needs 1st-order differencing) | |||

| TAOD550 | no further processing is necessary | no further processing is necessary | no further processing is necessary | 5.3726, 0.5543, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) |

| AAOD550 | no further processing is necessary | no further processing is necessary | 2.5479, 0.3662, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | no further processing is necessary |

| SAOD550 | no further processing is necessary | 3.3870, 0.1956, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | no further processing is necessary | 5.3992, 0.5460, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) |

| StAOD550 | 2.7938, 0.1749, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 3.8396, 0.1733, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 2.5888, 0.1616, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 5.5774, 0.5635, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) |

| SSAOD550 | 4.6631, 0.2990, 6 (needs deseasonalisation) | 1.5834, 0.4151, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | no further processing is necessary | 4.7182, 0.2903, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) |

| BCAOD550 | 5.5608, 0.4434, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 4.2254, 0.5087, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 4.9921, 0.5311, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 0.8177, 0.7104, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) |

| AE470–870 | 2.5659, 0.3821, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 2.6225, 0.3724, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 2.7621, 0.3072, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 3.8136, 0.5049, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) |

| SSA | 5.3253, 0.3308, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 5.3962, 0.3967, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 4.7512, 0.3834, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) | 6.0146, 0.4352, 6 (needs 1st-order differencing) |

Appendix A.5. Time Series Stationarity After Deseasonalisation and First-Order Differencing

| Parameter, q | WestMed | CentMed | EastMed | BalBSea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSN | 0.1369, 0.0463, 6, level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | |||

| TAOD550 | no further processing is necessary | no further processing is necessary | no further processing is necessary | 0.0101, 0.0103, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| AAOD550 | no further processing is necessary | no further processing is necessary | 0.0117, 0.0113, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | no further processing is necessary |

| SAOD550 | no further processing is necessary | 0.0086, 0.0083, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | no further processing is necessary | 0.0104, 0.0106, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| StAOD550 | 0.0145, 0.0139, 6, level/trend stationarity at 99%/97.4% CI | 0.0183, 0.0112, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0160, 0.0150, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0157, 0.0159, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| SSAOD550 | 0.0088, 0.0087, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0369, 0.0131, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | no further processing is necessary | 0.0083, 0.0083, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| BCAOD550 | 0.0160, 0.0127, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0109, 0.0095, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0150, 0.0116, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0185, 0.0120, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| AE470–870 | 0.0220, 0.02171, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0161, 0.0158, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0169, 0.0166, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0158, 0.0160, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

| SSA | 0.0290, 0.0235, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0254, 0.0253, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0239, 0.0238, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI | 0.0232, 0.0231, 6 level/trend stationarity at 90%/90% CI |

Appendix A.6. Granger-Causality Test

| Parameter, q | WestMed | CentMed | EastMed | BalBSea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAOD550 | overall regression RMSE = 0.0706, R2 = 0.6510, p-value = 0.0002 (≈100% CI) +0.1815 (96.5%) +0.0002·SSNt−1 (63.9%) −0.0004·SSNt−6 (98%) −0.0072·ΝΑΟΙt (88.8%) −0.0099·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (96.1%) +0.0068·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (86.1%) +0.0062·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (81.2%) +0.0050·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (72%) +0.0082·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (94.3%) −0.0387·ONI t−1 (70.1%) +0.0452·ONI t−2 (72.4%) −9.2806 × 10−5·t (99.7%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0430, R2 = 0.5714, p-value = 0.1947 (80.5% CI) +0.0001·SSNt−3 (67.4%) +0.0002·SSNt−4 (96.8%) +0.0037·ΝΑΟΙt (83.4%) +0.0150·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (94%) −0.0075·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (65%) −0.0110·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (81.6%) −0.0008·ONI t−2 (61.8%) −0.0004·ONI t−4 (85%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0573, R2 = 0.5969, p-value = 0.0440 (95.6% CI) +0.1216 (93.4%) −0.0002·SSNt−6 (89.5%) +0.0103·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (66.7%) +0.0011·ONI t−2 (65.5%) −0.0007·ONI t−3 (62.1%) −0.0009·ONI t−4 (73.3%) +0.0007·ONI t−6 (73.3%) −8.4831 × 10−5·t (99.9%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0405, R2 = 0.5710, p-value = 0.1819 (81.8% CI) −0.0438 (65.4%) +0.0002·SSNt−4 (95.2%) +0.0001·SSNt−5 (76.5%) +0.0103·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (82%) −0.0085·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (74.6%) −0.0160·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (96%) +0.0144·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (94.9%) +0.0006·ONIt−1 (62.6%) −0.0019·ONIt−2 (97.9%) +0.0015·ONIt−3 (99.2%) −0.0011·ONIt−4 (97.8%) +0.0006·ONIt−4 (70.2%) −2.6653 × 10−5·t (86.9%) |

| AAOD550 | overall regression RMSE = 0.0044, R2 = 0.6508, p-value = 0.0002 (≈100% CI) +0.0089 (90.1%) +1.1025 × 10−5·SSNt (62.8%) +2.5971 × 10−5·SSNt−1 (95.8%) +1.5868 × 10−5·SSNt−2 (73.3%) −2.1539 × 10−5·SSNt−6 (94.1%) −0.0004·SSNt−6 (98%) −0.0006·ΝΑΟΙt (94.1%) −0.0008·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (93.6%) +0.0004·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (84.2%) +0.0004·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (83.6%) +0.0004·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (86.5%) +0.0004·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (89.9%) −0.0022·ONI t−1 (64.4%) +0.0029·ONI t−2 (72.7%) +4.9699 × 10−6·t (98.9%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0042, R2 = 0.6930, p-value = 0.0575 (94.3% CI) +1.3261 × 10−5·SSNt (75.2%) +2.1955 × 10−5·SSNt−1 (93.7%) +1.4242 × 10−5·SSNt−2 (71.4%) −2.2672 × 10−5·SSNt−6 (96.3%) −0.0004·ΝΑΟΙt (90.4%) +0.0010·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (80.2%) +0.0011·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (86%) −0.0007·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (61.6%) −7.6620 × 10−5·ONI t−1 (70.4%) +0.0002·ONI t−2 (97.5%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0024, R2 = 0.5601, p-value = 0.3127 (68.7% CI) −0.0054 (94.6%) +7.7984 × 10−6·SSNt−3 (68.7%) +1.1722 × 10−6·SSNt−4 (88.7%) −5.4475 × 10−6·SSNt−6 (60.9%) +0.0007·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (86.6%) −4.4589 × 10−5·ONI t−2 (63%) +3.7864 × 10−5·ONI t−5 (75.7%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0031, R2 = 0.5616, p-value = 0.2955 (70.5% CI) +0.0064 (92.9%) +7.3445 × 10−6·SSNt−1 (60.2%) +9.5150 × 10−6·SSNt−5 (74.7%) −8.4786 × 10−6·SSNt−6 (71.1%) −0.0004·SSNt−6 (98%) −0.0003·ΝΑΟΙt (89.8%) +0.0012·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (95.6%) +0.0006·ΝΑΟΙt−2 (71.1%) +0.0008·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (82.8%) −0.0008·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (81.8%) −0.0005·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (67.3%) |

| SAOD550 | overall regression RMSE = 0.0666, R2 = 0.6551, p-value = 0.0001 (≈100% CI) +0.1726 (96.7%) −0.0004·SSNt−6 (94.7%) −0.0066·ΝΑΟΙt (88.1%) −0.0091·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (95.6%) +0.0064·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (86%) +0.0058·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (66.7%) +0.0046·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (70.4%) +0.0078·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (64.8%) −0.0366·ONIt−1 (70.2%) +0.0424·ONIt−2 (72.1%) −9.7801 × 10−5·t (99.9%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0406, R2 = 0.5699, p-value = 0.2090 (79.1% CI) +0.0001·SSNt−3 (67.1%) +0.0002·SSNt−4 (94.2%) −0.0066·ΝΑΟΙt (88.1%) +0.0136·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (92.8%) −0.0071·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (65.8%) −0.0106·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (82.6%) +0.0008·ONIt−2 (63.6%) −0.0007·ONIt−4 (85.1%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0540, R2 = 0.6094, p-value = 0.0167 (98.3% CI) +0.1173 (94.4%) −0.0001·SSNt (61.4%) −0.0002·SSNt−6 (89.7%) +0.0095·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (65.7%) −0.0366·ON t−1 (70.2%) +0.0010·ONI t−2 (61.2%) −0.0007·ONI t−3 (62.5%) −0.0008·ONI t−4 (80.3%) +0.0007·ONI t−4 (74.3%) −8.9362 × 10−5·t (≈100%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0389, R2 = 0.5761, p-value = 0.1547 (84.5% CI) −0.0417 (64.9%) +0.0003·SSNt−4 (97.2%) +0.0001·SSNt−5 (83.1%) +0.0001·SSNt−6 (70.3%) +0.0100·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (82.6%) −0.0077·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (71.2%) −0.0159·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (96.6%) +0.0148·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (96.2%) +0.0007·ONIt−1 (66.8%) −0.0018·ONIt−2 (97.9%) +0.0015·ONIt−3 (99.3%) −0.0011·ONIt−4 (98.2%) +0.0006·ONIt−5 (74.8%) −2.5458 × 10−5·t (86.6%) |

| DDAOD550 | overall regression RMSE = 0.0501, R2 = 0.6388, p-value = 0.0009 (≈100% CI) +0.0860 (84.3%) +0.0002·SSNt−1 (91.3%) +0.0002·SSNt−2 (67.9%) −0.0002·SSNt−6 (94.5%) −0.0065·ΝΑΟΙt (95.7%) −0.0086·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (98.9%) +0.0054·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (90.3%) +0.0045·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (81.9%) +0.0039·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (75.6%) +0.0038·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (78.1%) −0.0279·ONI t−1 (70.9%) +0.0417·ONI t−2 (84.3%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0482, R2 = 0.5741, p-value = 0.1713 (82.9% CI) +0.0001·SSNt−1 (68.7%) −0.0001·SSNt−4 (66.6%) −0.0003·SSNt−6 (97.6%) −0.0041·ΝΑΟΙt (83.7%) +0.0084·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (64.5%) +0.0144·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (89.3%) −0.0009·ONI t−1 (71.1%) +0.0025·ONI t−2 (99%) −0.0006·ONI t−3 (63.4%) −0.0008·ONI t−4 (81.6%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0516, R2 = 0.4895, p-value = 0.9653 (3.5% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0298, R2 = 0.4923, p-value = 0.9577 (4.2% CI) |

| StAOD550 | overall regression RMSE = 0.0149, R2 = 0.5941, p-value = 0.0534 (94.7% CI) −6.3900 × 10−5·SSNt−1 (86.7%) +4.4276 × 10−5·SSNt−3 (64.9%) +8.9313 × 10−5·SSNt−4 (95%) +0.0023·ΝΑΟΙt (98.4%) −0.0040·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (99.9%) −0.0034·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (99.9%) +0.0008·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (62.5%) −0.0094·ONI t−1 (77%) −0.0080·ONI t−4 (62.7%) +0.0082·ONI t−5 (67.4%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0220, R2 = 0.4865, p-value = 0.9722 (2.8% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0170, R2 = 0.5279, p-value = 0.7142 (28.6% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0263, R2 = 0.5944, p-value = 0.0522 (94.8% CI) +0.0002·SSNt−4 (95.9%) +0.0001·SSNt−5 (95.9%) +0.0001·SSNt−6 (90.8%) +0.0106·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (96.6%) −0.0049·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (68.7%) −0.0077·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (87%) +0.0084·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (91.8%) +0.0005·ONI t−1 (68.5%) −0.0013·ONI t−2 (98.1%) +0.0010·ONI t−3 (99.2%) −0.0006·ONI t−4 (95.3%) +0.0003·ONI t−5 (67.3%) |

| SSAOD550 | overall regression RMSE = 0.0029, R2 = 0.5269, p-value = 0.7252 (27.5% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0053, R2 = 0.6028, p-value = 0.0286 (97.1% CI) −0.0094 (87.7%) +2.3837 × 10−5·SSNt−3 (84%) −1.5358 × 10−5·SSNt−5 (71.2%) −1.2409 × 10−5·SSNt−6 (62.8%) +0.0006·NAOI t (92.8%) +0.0009·NAOI t−5 (62.1%) +0.0010·NAOI t−6 (68.3%) −0.0001·ONIt−2 (78.6%) +0.0003·ONIt−3 (≈100%) −0.0001·ONIt−4 (96.7%) +0.0002·ONIt−5 (98%) −6.4949 × 10−5·ONIt−6 (74.2%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0053, R2 = 0.6084, p-value = 0.0182 (98.2% CI) +0.0182 (99.7%) +1.3741 × 10−6·SSNt−1 (64.4%) +1.3953 × 10−5·SSNt−4 (61.8%) −1.2409 × 10−5·SSNt−6 (62.8%) +0.0002·ONIt−1 (96.5%) −0.0001·ONIt−2 (76.1%) +0.0001·ONIt−3 (94.3%) +9.5472 × 10−6·t (≈100%) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0029, R2 = 0.5386, p-value = 0.5862 (41.4% CI) |

| BCAOD550 | overall regression RMSE = 0.0008, R2 = 0.5239, p-value = 0.7564 (24.4% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0009, R2 = 0.5208, p-value = 0.7876 (21.2% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0008, R2 = 0.5240, p-value = 0.7560 (24.4% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0016, R2 = 0.4916, p-value = 0.9599 (4% CI) |

| AE470–870 | overall regression RMSE = 0.1117, R2 = 0.5461, p-value = 0.4890 (51.1% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.1478, R2 = 0.5188, p-value = 0.8056 (19.4% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.1482, R2 = 0.5050, p-value = 0.9050 (9.5% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.1327, R2 = 0.4475, p-value = 0.9993 (0.1% CI) |

| SSA | overall regression RMSE = 0.0038, R2 = 0.5187, p-value = 0.8067 (19.3% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0051, R2 = 0.4881, p-value = 0.9687 (3.1% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0052, R2 = 0.5233, p-value = 0.7632 (23.7% CI) | overall regression RMSE = 0.0051, R2 = 0.5758, p-value = 0.1571 (84.3% CI) −0.0087 (86.3%) +1.4672 × 10−5·SSNt (70.4%) +2.8446 × 10−5·SSNt−1 (95.1%) +2.5693 × 10−5·SSNt−3 (88.8%) +1.7178 × 10−5·SSNt−4 (73.4%) +1.7562 × 10−5·SSNt−5 (79.7%) +3.0049 × 10−5·SSNt−6 (97.6%) +0.0004·NAOIt (81.9%) +0.0015·NAOI t−2 (89%) −0.0013·NAOI t−4 (81.7%) +7.0650 × 10−5·ONIt−5 (70.3%) |

| DARF | overall regression RMSE = 2.4927, R2 = 0.6433, p-value = 0.0005 (≈100% CI) +0.0070·SSNt (68.9%) +0.0136·SSNt−1 (94.2%) +0.0100·SSNt−2 (78.8%) −0.0116·SSNt−6 (92.9%) −0.3498·NAOIt (97.2%) −0.3853·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (97.8%) +0.2425·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (86.5%) +0.3482·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (96.4%) +0.3333·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (95.6%) +0.2160·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (84.3%) +1.3390·ONIt−2 (63.9%) +0.0026·t (98.3%) | overall regression RMSE = 2.2501, R2 = 0.5875, p-value = 0.0819 (91.8% CI) −0.2267 (87.7%) +0.0075·SSNt (77.3%) +0.0101·SSNt−1 (88.6%) +0.0068·SSNt−2 (65.2%) −0.0125·SSNt−6 (96.5%) −0.2632·NAOIt (94.3%) +0.5943·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (83.7%) +0.7397·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (92.4%) +0.3510·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (60%) +0.0714·ONI t−2 (87.8%) +0.0018·t (93.6%) | overall regression RMSE = 1.8977, R2 = 0.5922, p-value = 0.0604 (94% CI) +0.0092·SSNt (92%) +0.0103·SSNt−1 (94.5%) +0.0080·SSNt−2 (81%) +0.0056·SSNt−3 (64.3%) +0.0053·SSNt−5 (69.2%) −0.0065·SSNt−6 (81%) −0.2250·NAOIt (94.6%) +0.5957·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (90.2%) +0.4686·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (81.7%) +0.3951·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (74.5%) +0.0705·ONIt−2 (92.9%) −0.0258·ONIt−3 (66.9%) +0.0023·t (99.5%) | overall regression RMSE = 1.8606, R2 = 0.5822, p-value = 0.1116 (88.8% CI) +0.0056·SSNt (72%) +0.0063·SSNt−1 (77%) +0.0041·SSNt−2 (69.8%) +0.0062·SSNt−5 (77.7%) −0.0069·SSNt−6 (84.7%) −0.2535·NAOIt (97.3%) +0.5968·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (90.9%) +0.3334·ΝΑΟΙt−2 (67.5%) +0.4841·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (84%) −0.4100·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (74.7%) −0.3822·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (73.9%) |

| netSWRBOA,CS,A | overall regression RMSE = 60.8066 W−2, R2 = 0.6209, p-value = 0.0060 (99.4% CI) +130.6428 (92.3%) +0.2024·SSNt (76.9%) +0.2629·SSNt−1 (86.9%) +0.2234·SSNt−2 (74.6%) −0.1976·SSNt−6 (79.5%) −10.3043·NAOIt (99.2%) −4.8354·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (76.2%) +6.7794·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (91.3%) +10.2190·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (98.8%) +8.8681·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (97.2%) | overall regression RMSE = 67.8601 W−2, R2 = 0.5954, p-value = 0.0488 (95.1% CI) +98.0516 (79.1%) +0.2576·SSNt (83%) +0.2743·SSNt−1 (84.5%) −0.2643·SSNt−6 (86.3%) −12.0709·NAOIt (99.6%) +19.5626·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (88%) +10.2190·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (98.8%) −0.9205·ONIt−3 (66.8%) | overall regression RMSE = 65.3489 W−2, R2 = 0.5971, p-value = 0.0435 (95.7% CI) +107.7180 (84.8%) +0.2525·SSNt (83.9%) +0.2743·SSNt−1 (85.2%) −0.2606·SSNt−6 (87.2%) −11.5600·NAOIt (99.6%) +18.9829·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (88.3%) +10.2190·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (98.8%) −0.8794·ONIt−3 (66.4%) | overall regression RMSE = 78.0674 W−2, R2 = 0.5655, p-value = 0.0485 (95.2% CI) +0.3042·SSNt (84.1%) +0.3203·SSNt−1 (85.1%) +0.2123·SSNt−2 (60.2%) −0.3213·SSNt−6 (88.4%) −14.0072·NAOIt (99.6%) +21.7551·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (86.7%) −1.0693·ONIt−3 (67.2%) +0.0299·t (61.9%) |

| netLWRBOA,CS,A | overall regression RMSE = 5.9091 W−2, R2 = 0.5927, p-value = 0.0586 (94.1% CI) −96.7403 (99.9%) −0.0168·SSNt (69.3%) +0.0253·SSNt−1 (86.5%) −0.0234·SSNt−2 (78%) −0.0250·SSNt−3 (81.5%) −0.0161·SSNt−5 (68%) +0.0150·SSNt−6 (67.8%) +0.5868·NAOIt (88%) +0.4046·ΝΑΟΙt−2 (70%) −0.9142·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (98%) −1.0876·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (99.4%) +8.8681·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (97.2%) −3.1520·ONIt−3 (61.9%) +3.5934·ONIt−4 (68.5%) −3.4192·ONIt−5 (69.4%) +1.9677·ONIt−6 (70.6%) | overall regression RMSE = 4.3512 W−2, R2 = 0.5972, p-value = 0.1321 (86.8% CI) −103.6478 (≈100%) +0.0124·SSNt (69.7%) +0.0147·SSNt−1 (76.6%) −0.0161·SSNt−4 (77.7%) −0.0104·SSNt−6 (64.1%) −0.9157·NAOIt (99.9%) −0.9835·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (76.8%) −1.3072·ΝΑΟΙt−2 (90.1%) −1.0363·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (78.3%) −0.1569·ONIt−1 (95.8%) +0.1914·ONIt−2 (96.7%) −0.1014·ONIt−5 (91.8%) +0.1151·ONIt−6 (98.5%) +0.0027·t (84.2%) | overall regression RMSE = 3.3649 W−2, R2 = 0.5811, p-value = 0.1191 (88.1% CI) −107.7368 (≈100%) +0.0091·SSNt−1 (65.8%) +0.0093·SSNt−2 (61.1%) −0.5049·NAOIt (98.5%) −0.9429·ΝΑΟΙt−2 (87.6%) −1.3072·ΝΑΟΙt−2 (90.1%) −0.0961·ONIt−1 (89.4%) +0.1211·ONIt−2 (92%) +0.0550·ONIt−3 (75.7%) −0.0732·ONIt−4 (93%) +0.0666·ONIt−6 (93.3%) +0.0058·t (≈100%) | overall regression RMSE = 4.4422 W−2, R2 = 0.5679, p-value = 0.2283 (77.2% CI) −95.0348 (≈100%) −0.0167·SSNt (82.5%) −1.0330·ΝΑΟΙt−2 (79.8%) +0.8875·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (71.9%) +0.7096·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (61.8%) +0.1469·ONIt−2 (89.3%) −0.0670·ONIt−4 (79.2%) +0.0528·ONIt−6 (72.9%) +0.0085·t (≈100%) |

| COD | overall regression RMSE = 5.8037, R2 = 0.5935, p-value = 0.0554 (94.5% CI) +15.6029 (97.3%) −0.0170·SSNt−3 (64.2%) +0.5651·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (85.1%) −0.8495·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (97.2%) −0.8446·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (97.2%) −1.3957·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (≈100%) −3.0681·ONIt−4 (61.8%) | overall regression RMSE = 8.9935, R2 = 0.6002, p-value = 0.0346 (96.5% CI) +25.36029 (98.5%) −0.0388·SSNt (88%) −0.0307·SSNt−1 (77%) −0.0304·SSNt−2 (71%) +0.0267·SSNt−6 (74.4%) +2.1672·ΝΑΟΙt (≈100%) −1.7244·ΝΑΟΙt−1 (68.9%) −2.3902·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (84.8%) −0.1864·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (84.4%) +1.6426·ΝΑΟΙt−5 (65.7%) +2.9777·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (92.9%) +0.1864·ONIt−3 (86.1%) −0.1703·ONIt−4 (88.6%) +0.1215·ONIt−5 (68.8%) | overall regression RMSE = 10.0918, R2 = 0.6140, p-value = 0.0113 (98.9% CI) +20.85789 (92.7%) −0.0457·SSNt (89.8%) −0.0286·SSNt−1 (68.1%) +0.0351·SSNt−4 (74.8%) +0.0512·SSNt−6 (94.7%) +3.0228·ΝΑΟΙt (≈100%) −2.8010·ΝΑΟΙt−3 (86.6%) −3.5270·ΝΑΟΙt−4 (94%) +2.4207·ΝΑΟΙt−6 (81%) −0.1072·ONIt−4 (74.4%) | overall regression RMSE = 6.6790, R2 = 0.5492, p-value = 0.4486 (55.1% CI) |

Appendix A.7. Summary of Correlations

| Parameters in Pair | WestMed | CentMed | EastMed | BalBSea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAOD550–SSN | +0.206 *** | +0.368 * | ||

| SAOD550–SSN | +0.215 *** | +0.299 * | +0.367 * | |

| StAOD550–SSN | +0.260 *** | +0.236 *** | +0.323 * | +0.353 * |

| SSAOD550–SSN | −0.306 * | −0.401 * | ||

| SSA–SSN | +0.246 *** | +0.239 *** | +0.306 * | |

| StAOD550–NAOI | +0.295 * | |||

| AE470–870–NAOI | +0.324 * | +0.314 * | ||

| SSA–NAOI | +0.246 *** | +0.239 *** | +0.306 * | |

| DARF–NAOI | −0.294 * | |||

| COD–NAOI | +0.235 *** | −0.316 * | ||

| AAOD550–ONI | −0.306 * | |||

| DDAOD550–ONI | −0.284 * | −0.333 * | ||

| StAOD550–ONI | +0.225 *** | +0.295 * | ||

| AE470–870–ONI | +0.219 *** | +0.233 *** | +0.331 * | |

| DARF–ONI | −0.334 * |

References

- Iqbal, M. An Introduction to Solar Radiation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983; p. 408. ISBN 978-0-323-15181-8. [Google Scholar]

- Donateo, A.; Feudo, T.L.; Marinoni, A.; Dinoi, A.; Avolio, E.; Merico, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Bonasoni, P. Characterization of in Situ Aerosol Optical Properties at Three Observatories in the Central Mediterranean. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhre, G.; Myhre, C.E.L.; Samset, B.H.; Storelvmo, T. Aerosols and Their Relation to Global Climate and Climate Sensitivity. Nat. Educ. 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Kambezidis, H.D.; Adamopoulos, A.D.; Kassomenos, P.A. On the Characterization of Aerosols Using the Ångström Exponent in the Athens Area. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2006, 68, 2147–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Kahn, R.A.; Randerson, J.T.; Diner, D.J. Quantifying Aerosol Direct Radiative Effect with Multiangle Imaging Spectroradiometer Observations: Top-of-Atmosphere Albedo Change by Aerosols Based on Land Surface Types. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D02109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wurzler, S.; Levin, Z.; Reisin, T.G. Interactions of Mineral Dust Particles and Clouds: Effects on Precipitation and Cloud Optical Properties. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2002, 107, AAC 19-1–AAC 19-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurzler, S.; Reisin, T.G.; Levin, Z. Modification of Mineral Dust Particles by Cloud Processing and Subsequent Effects on Drop Size Distributions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2000, 105, 4501–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metangley, S.; Middey, A.; Kadaverugu, R. Modern Methods to Explore the Dynamics between Aerosols and Convective Precipitation: A Critical Review. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 2024, 106, 101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Carlson, B.E.; Yung, Y.L.; Lv, D.; Hansen, J.; Penner, J.E.; Liao, H.; Ramaswamy, V.; Kahn, R.A.; Zhang, P.; et al. Scattering and Absorbing Aerosols in the Climate System. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio, T.; di Sarra, A.; Junkermann, W.; Cacciani, M.; Fiocco, G.; Fuà, D. Tropospheric Aerosols in the Mediterranean: 1. Microphysical and Optical Properties. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.V.; Jacob, D.J.; Yantosca, R.M.; Chin, M.; Ginoux, P. Global and Regional Decreases in Tropospheric Oxidants from Photochemical Effects of Aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, 4097–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulmala, M.; Arola, A.; Nieminen, T.; Riuttanen, L.; Sogacheva, L.; de Leeuw, G.; Kerminen, V.-M.; Lehtinen, K.E.J. The First Estimates of Global Nucleation Mode Aerosol Concentrations Based on Satellite Measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 10791–10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.R.; Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Manchanda, R.K.; Sreenivasan, S. Characteristics of Aerosols over Hyderabad in Southern Peninsular India: Synergy in the Classification Techniques. Ann. Geophys. 2012, 30, 1393–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choobari, O.A.; Zawar-Reza, P.; Sturman, A. The Global Distribution of Mineral Dust and Its Impacts on the Climate System: A Review. Atmos. Res. 2014, 138, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambezidis, H.D. The Solar Resource. In Comprehensive Renewable Energy; Letcher, T.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; Volume 3, pp. 26–117. ISBN 978-0-12-819727-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.M.; Won, Y.I.; Jeong, M.J.; Kim, K.M.; Shin, D.B.; Lee, Y.R.; Cho, Y.J. Intensity of Climate Variability Derived from the Satellite and MERRA Reanalysis Temperatures: AO, ENSO, and QBO. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2013, 95–96, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, W.A.; Roeckner, E. ENSO Impact on Midlatitude Circulation Patterns in Future Climate Change Projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L05711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abish, B.; Mohanakumar, K. Absorbing Aerosol Variability over the Indian Subcontinent and Its Increasing Dependence on ENSO. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 106, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laken, B.A.; Stordal, F. Are There Statistical Links between the Direction of European Weather Systems and ENSO, the Solar Cycle or Stratospheric Aerosols? R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 150320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirov, B.; Georgieva, K. Long-Term Variations and Interrelations of ENSO, NAO and Solar Activity. Phys. Chem. Earth 2002, 27, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzina, B.; García-Serrano, J.; Bladé, I.; Kucharski, F. Dynamics of the ENSO Teleconnection and NAO Variability in the North Atlantic-European Late Winter. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casselman, J.W.; Jiménez-Esteve, B.; Domeisen, D.I.V. Modulation of the El Niño Teleconnection to the North Atlantic by the Tropical North Atlantic During Boreal Spring and Summer. Weather Clim. Dyn. 2022, 3, 1077–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casselman, J.W.; Taschetto, A.S.; Domeisen, D.I.V. Nonlinearity in the Pathway of El Ninõ-Southern Oscillation to the Tropical North Atlantic. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 7277–7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casselman, J.W.; Lübbecke, J.F.; Bayr, T.; Huo, W.; Wahl, S.; Domeisen, D.I.V. The Teleconnection of Extreme El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Events to the Tropical North Atlantic in Coupled Climate Models. Weather Clim. Dyn. 2023, 4, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Serrano, J.; Cassou, C.; Douville, H.; Giannini, A.; Doblas-Reyes, F.J. Revisiting the ENSO Teleconnection to the Tropical North Atlantic. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 6945–6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xie, M.; Fang, K.; Tarasick, D.W.; Wang, H.; Meng, L.; Cheng, X.; Han, H.; Zhang, X. ENSO Teleconnection to Interannual Variability in Carbon Monoxide Over the North Atlantic European Region in Spring. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 894779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, P.; Baldi, M.; Ilani, R.; Krichak, S.; Price, C.; Rodó, X.; Saaroni, H.; Ziv, B.; Kishcha, P.; Barkan, J.; et al. Chapter 2 Relations Between Climate Variability in the Mediterranean Region and the Tropics: ENSO, South Asian and African Monsoons, Hurricanes and Saharan Dust. In Developments in Earth and Environmental Sciences; Lionello, P., Malanotte-Rizzoli, P., Boscolo, R., Eds.; Mediterranean; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 4, pp. 149–177. [Google Scholar]

- Urdiales-Flores, D.; Zittis, G.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Osipov, S.; Klingmüller, K.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Kanakidou, M.; Economou, T.; Lelieveld, J. Drivers of Accelerated Warming in Mediterranean Climate-Type Regions. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Remote ENSO Influence on Mediterranean Sky Conditions During Late Summer and Autumn: Evidence for a Slowly Evolving Atmospheric Bridge. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 130, 2409–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubhi, Y.; Ali, G. Impact of El Niño-Southern Oscillation on Dust Variability during the Spring Season over the Arabian Peninsula. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambezidis, H.D. Atmospheric Processes over the Broader Mediterranean Region: Effect of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation? Atmosphere 2024, 15, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westervelt, D.M.; Conley, A.J.; Fiore, A.M.; Lamarque, J.F.; Shindell, D.T.; Previdi, M.; Mascioli, N.R.; Faluvegi, G.; Correa, G.; Horowitz, L.W. Connecting Regional Aerosol Emissions Reductions to Local and Remote Precipitation Responses. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 12461–12475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yin, Z.Y.; An, Z. Global Impact of ENSO on Dust Activities with Emphasis on the Key Region from the Arabian Peninsula to Central Asia. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2021, 126, e2020JD034068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Kumar, S.P. ENSO Modulation of Interannual Variability of Dust Aerosols over the Northwest Indian Ocean. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 1287–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brönnimann, S.; Luterbacher, J.; Staehelin, J.; Svendby, T.M.; Hansen, G.; Svenøe, T. Extreme Climate of the Global Troposphere and Stratosphere in 1940–42 Related to El Niño. Nature 2004, 431, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniazzo, T.; Scaife, A.A. The Influence of ENSO on Winter North Atlantic Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L24704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamon, R.J. The Triple-Dip La Niña of 2020–22: Updates to the Correlation of ENSO with the Termination of Solar Cycles. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1204191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, L. Modulation of the Solar Activity on the Connection between the NAO and the Tropical Pacific SST Variability. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1147582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, U.; Kanakidou, M. Impacts of East Mediterranean Megacity Emissions on Air Quality. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 6335–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohl, A.; Aamaas, B.; Amann, M.; Baker, L.H.; Bellouin, N.; Berntsen, T.K.; Boucher, O.; Cherian, R.; Collins, W.; Daskalakis, N.; et al. Evaluating the Climate and Air Quality Impacts of Short-Lived Pollutants. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 10529–10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, M.; Metzger, S.; Mamouri, R.E.; Astitha, M.; Barrie, L.; Levin, Z.; Lelieveld, J. Dust-Air Pollution Dynamics over the Eastern Mediterranean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 9173–9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Rashki, A.; Dumka, U.C.; Mofidi, A.; Kambezidis, H.D.; Psiloglou, B.E.; Karagiannis, D.; Petrinoli, K.; Gavriil, A. Atmospheric Dynamics Associated with Exceptionally Dusty Conditions over the Eastern Mediterranean and Greece in March 2018. Atmos. Res. 2019, 218, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiridis, V.; Wandinger, U.; Marinou, E.; Giannakaki, E.; Tsekeri, A.; Basart, S.; Kazadzis, S.; Gkikas, A.; Tayler, M.; Baldasano, J.; et al. Optimizing Saharan Dust CALIPSO Retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2013, 13, 14749–14795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Kambezidis, H.D.; Nastos, P.T.; Kosmopoulos, P.G. Study on an Intense Dust Storm over Greece. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 6884–6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizza, U.; Barnaba, F.; Marcello Miglietta, M.; Mangia, C.; Di Liberto, L.; Dionisi, D.; Costabile, F.; Grasso, F.; Paolo Gobbi, G. WRF-Chem Model Simulations of a Dust Outbreak over the Central Mediterranean and Comparison with Multi-Sensor Desert Dust Observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, M.; Córdoba-Jabonero, C.; Barreto, A.; Welton, E.J.; Gil-Díaz, C.; Carvajal-Pérez, C.V.; Comerón, A.; García, O.; García, R.; López-Cayuela, M.Á.; et al. Volcanic Eruption of Cumbre Vieja, La Palma, Spain: A First Insight to the Particulate Matter Injected in the Troposphere. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A.; Matson, M. Circumglobal Transport of the El Chichón Volcanic Dust Cloud. Science 1983, 221, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kahn, R.A.; Chaloulakou, A.; Koutrakis, P. Analysis of the Impact of the Forest Fires in August 2007 on Air Quality of Athens Using Multi-Sensor Aerosol Remote Sensing Data, Meteorology and Surface Observations. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 3310–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Klingmueller, K.; Fredj, E.; Lelieveld, J.; Rudich, Y.; Koren, I. Radiative Signature of Absorbing Aerosol over the Eastern Mediterranean Basin. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 7213–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.P.; Keenlyside, N.; Li, C. ENSO Teleconnections in Terms of Non-NAO and NAO Atmospheric Variability. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 61, 2717–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadgarai, S.; Kumar, V.; Pradhan, P.K. The Connection between Extreme Precipitation Variability over Monsoon Asia and Large-Scale Circulation Patterns. Atmos. 2021, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. South Asian Monsoon Extremes and Climate Change. In Extremes in Atmospheric Processes and Phenomenon: Assessment, Impacts and Mitigation, Disaster Resilience and Green Growth; Saxena, P., Shukla, A., Gupta, A.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 59–86. ISBN 978-981-16-7727-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Kalapureddy, M.C.R.; Devara, P.C.S.; Kosmopoulos, P.G.; Nastos, P.T.; Krishna Moorthy, K.; Kambezidis, H.D. Spatio-Temporal Aerosol Optical Characteristics over the Arabian Sea during the PreMonsoon Season. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2009, 9, 22223–22269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochet, A.; Dodet, G.; Ardhuin, F.; Hemer, M.; Young, I. Sea State Decadal Variability in the North Atlantic: A Review. Climate 2021, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vencloviene, J.; Kiznys, D.; Zaltauskaite, J. Statistical Associations Between Geomagnetic Activity, Solar Wind, Solar Proton Events, and Winter NAO and AO Indices. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2021EA002179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Li, L.Z.; Kanakidou, M.; Hatzianastassiou, N.; Seze, G.; Le Treut, H. Winter Weather Regimes over the Mediterranean Region: Their Role for the Regional Climate and Projected Changes in the Twenty-First Century. Clim. Dyn. 2013, 41, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsa, E.; Flocas, H.A.; Hatzaki, M.; Kouroutzoglou, J.; Rudeva, I.; Simmonds, I. Climatological Study of Frontal Precipitation over the Mediterranean. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugé, T.; Nabat, P.; Mallet, M.; Somot, S. Future Evolution of Aerosols and Implications for Climate Change in the Euro-Mediterranean Region Using the CNRM-ALADIN63 Regional Climate Model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 7639–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J.G.; Leptoukh, G. Online Analysis Enhances Use of NASA Earth Science Data. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union. 2007, 88, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.; Wu, R.; Aldabash, M. Long-Term AOD Trend Assessment over the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Comparative Study Including a New Merged Aerosol Product. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 238, 117736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Huang, G.; Wang, L.; Wei, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, L.; Feng, L. Validation and Comparison of Long-Term Accuracy and Stability of Global Reanalysis and Satellite Retrieval AOD. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkavilli, S.K.; Prasad, A.A.; Taylor, R.A.; Huang, J.; Mitchell, R.M.; Troccoli, A.; Kay, M.J. Assessment of Atmospheric Aerosols from Two Reanalysis Products over Australia. Atmos. Res. 2019, 215, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, A.; Krauter, S. Validation and Performance of Satellite Meteorological Dataset MERRA-2 for Solar and Wind Applications. Energies 2021, 14, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.C.; Huang, C.H.; Marshak, A.; Slutsker, I.; Giles, D.M.; Holben, B.N.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Wiscombe, W.J. Cloud Optical Depth Retrievals from the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) Cloud Mode Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D14202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Q.; Joseph, E.; Duan, M. Retrievals of Thin Cloud Optical Depth from a Multifilter Rotating Shadowband Radiometer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2004, 109, D02201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldering, A.; Kulawik, S.S.; Worden, J.; Bowman, K.; Osterman, G. Implementation of Cloud Retrievals for TES Atmospheric Retrievals: 2. Characterization of Cloud Top Pressure and Effective Optical Depth Retrievals. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D16S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. On the Solar Radiation Budget and the Cloud Absorption Anomaly Debate. In World Scientific Series on Asia-Pacific Weather and Climate; World Scientific: Singapore, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 437–456. ISBN 978-981-238-704-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Thorne, P.W.; Banzon, V.F.; Boyer, T.; Chepurin, G.; Lawrimore, J.H.; Menne, M.J.; Smith, T.M.; Vose, R.S.; Zhang, H.-M. Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, Validations, and Intercomparisons. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 8179–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Dool, H.M.; Saha, S.; Johansson, Å. Empirical Orthogonal Teleconnections. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Van den Dool, H. Sensitivity of Teleconnection Patterns to the Sign of Their Primary Action Center. Mon. Weather Rev. 2003, 131, 2885–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnston, A.G.; Livezey, R.E. Classification, Seasonality and Persistence of Low-Frequency Atmospheric Circulation Patterns. Mon. Weather Rev. 1987, 115, 1083–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhall, C.G.; Self, S. The Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI): An Estimate of Explosive Magnitude for Historical Volcanism. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1982, 87, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, A.; Amoruso, S.; Damiano, R.; Scollo, S.; Sellitto, P.; Boselli, A. Optical and Microphysical Characterization of Atmospheric Aerosol in the Central Mediterranean During Simultaneous Volcanic Ash and Desert Dust Transport Events. Atmos. Res. 2022, 271, 106099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, S.; Salmatonidis, A.; Querol, X.; Tassone, A.; Andreoli, V.; Bencardino, M.; Pirrone, N.; Sprovieri, F.; Naccarato, A. Contribution of Volcanic and Fumarolic Emission to the Aerosol in Marine Atmosphere in the Central Mediterranean Sea: Results from Med-Oceanor 2017 Cruise Campaign. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lorenzo, A.; Enriquez-Alonso, A.; Calbó, J.; González, J.-A.; Wild, M.; Folini, D.; Norris, J.R.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M. Fewer Clouds in the Mediterranean: Consistency of Observations and Climate Simulations. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigl, M.; Toohey, M.; McConnell, J.R.; Cole-Dai, J.; Severi, M. Volcanic Stratospheric Sulfur Injections and Aerosol Optical Depth During the Holocene (Past 11 500 Years) from a Bipolar Ice-Core Array. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 3167–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallos, G.; Solomos, S.; Kushta, J.; Mitsakou, C.; Spyrou, C.; Bartsotas, N.; Kalogeri, C. Natural and Anthropogenic Aerosols in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: Possible Impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 488–489, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Hitchcock, P.; Mahowald, N.M.; Domeisen, D.I.V.; Hamilton, D.S.; Li, L.; Marticorena, B.; Kanakidou, M.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Aboagye-Okyere, A. Stratospheric Impacts on Dust Transport and Air Pollution in West Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, A.; Marra, F.; Messori, G.; Pinto, J.G.; Raveh-Rubin, S.; Yosef, Y.; Zittis, G. Extreme Weather and Societal Impacts in the Eastern Mediterranean. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2022, 13, 749–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Hansen, J.E.; McCormick, M.P.; Pollack, J.B. Stratospheric Aerosol Optical Depths, 1850–1990. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1993, 98, 22987–22994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serykh, I.V. El Niño–Southern Oscillation Prediction Based on the Global Atmospheric Oscillation in CMIP6 Models. Climate 2025, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinou, E.; Amiridis, V.; Binietoglou, I.; Solomos, S.; Proestakis, E.; Konsta, D.; Tsikerdekis, A.; Papagiannopoulos, N.; Vlastou, G.; Zanis, P.; et al. 3D Evolution of Saharan Dust Transport towards Europe Based on a 9-Year EARLINET-Optimized CALIPSO Dataset. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2016, 17, 5893–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambezidis, H.D. The Solar Radiation Climate of Greece. Climate 2021, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ta, Z.; Wang, P.; He, Q.; Gao, J.; et al. The Influence of Dust Aerosols on Solar Radiation and Near-Surface Temperature during a Severe Duststorm Transport Episode. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1126302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, E.; Tuna Tuygun, G.; Elbir, T. Application of Aerosol Classification Methods Based on AERONET Version 3 Product over Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 2226–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiapello, I.; Formenti, P.; Mbemba Kabuiku, L.; Ducos, F.; Tanré, D.; Dulac, F. Aerosol Optical Properties Derived from POLDER-3/PARASOL (2005–2013) over the Western Mediterranean Sea—Part 2: Spatial Distribution and Temporal Variability. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 12715–12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Kosmopoulos, P.; Kambezidis, H.D.; Nastos, P.T. Aerosol Climatology and Discrimination of Different Types over Athens, Greece, Based on MODIS Data. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 7315–7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, M.; Dubovik, O.; Nabat, P.; Dulac, F.; Kahn, R.; Sciare, J.; Paronis, D.; Leon, J.F. Absorption Properties of Mediterranean Aerosols Obtained from Multi-Year Ground-Based and Satellite Remote Sensing Observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2013, 13, 9195–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, W.I.; Durant, A.J. El Chichón Volcano, April 4, 1982: Volcanic Cloud History and Fine Ash Fallout. Nat. Hazards 2009, 51, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.A.; Timmreck, C.; Giorgetta, M.A.; Graf, H.-F.; Stenchikov, G. Simulation of the Climate Impact of Mt. Pinatubo Eruption Using ECHAM5—Part 1: Sensitivity to the Modes of Atmospheric Circulation and Boundary Conditions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A. Climate Model Simulations of the Effects of the El Chichon Eruption. Geofis. Int. 1984, 23, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi-Jun, S.; Shand, L.; Li, B. Tracing the Impacts of Mount Pinatubo Eruption on Global Climate Using Spatially-Varying Changepoint Detection. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2025, 19, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibzadeh, M.; Alam, K.; Abedini, Y.; Bidokhti, A.A. Classification of Aerosols Using Multiple Clustering Techniques over Zanjan, Iran, During 2010–2014. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 99, 02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapureddy, M.C.R.; Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Ernest Raj, P.; Devara, P.C.S.; Kambezidis, H.D.; Kosmopoulos, P.G.; Nastos, P.T. Identification of Aerosol Type over the Arabian Sea in the Premonsoon Season During the Integrated Campaign for Aerosols, Gases and Radiation Budget (ICARB). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D17203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banja, M.; Đukanović, G.; Belis, C.A. Status of Air Pollutants and Greenhouse Gases in the Western Balkans: Benchmarking the Accession Process Progress on Environment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2020; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, E.G.; Reddy, P.; Ryan, S.; Deluisi, J.J. Features and Effects of Aerosol Optical Depth Observed at Mauna Loa, Hawaii: 1982–1992. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1994, 99, 8295–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herber, A.; Thomason, L.W.; Radionov, V.F.; Leiterer, U. Comparison of Trends in the Tropospheric and Stratospheric Aerosol Optical Depths in the Antarctic. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1993, 98, 18441–18447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.S.; Stowe, L.L. Using the NOAA/AVHRR to Study Stratospheric Aerosol Optical Thicknesses Following the Mt. Pinatubo Eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1994, 21, 2215–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toohey, M.; Sigl, M. Volcanic Stratospheric Sulfur Injections and Aerosol Optical Depth from 500ĝ€BCE to 1900ĝ€CE. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 809–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]