1. Introduction

The principal cause of global warming is recognized as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, predominantly from burning fossil fuels [

1]. In 2019, over a quarter of the EU’s GHG emissions were caused by transportation [

2]. As the transportation sector is responsible for a considerable proportion of these emissions, sustainable transportation must be a part of any climate change mitigation strategy. Electric vehicles (EVs) are widely considered to be more environmentally and economically efficient than internal combustion engine-based vehicles (ICEVs), and as the technology matures and availability increases [

3], governments around the world are beginning to phase out ICEVs and promote EV adoption; for example, the UK has recently legislated to end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 [

4]. However, while research to date has addressed the modelling, evaluation, or presentation of new EV methods or technologies, the end-user’s perspective has largely been ignored [

5], despite the fact that the widespread adoption of EVs will depend on meeting consumers’ economic, social, and environmental demands.

This study foregrounds potential end-users’ requirements in respect of EVs and identifies the key technical, social, financial, infrastructure, and policy barriers to their widespread adoption, using Saudi Arabia as a case study, since, according to Chidambaram [

6], limited adoption of EVs in developing countries is a matter of concern. In doing so, it builds on a previous paper which explored ICEV drivers’ perceptions of EVs and the factors they found most attractive [

7], with particular reference to the Saudi context. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) presents an interesting context within which to examine end-users’ perceptions of EVs and the barriers to their widespread adoption. The country has long been a major producer of oil, but it now has ambitious plans to reduce its GHG emissions, with the aim of achieving net-zero by 2060 [

8]. This will require much greater use of public transport and the widespread adoption of EVs [

9,

10], and the country aims to become a regional hub for EV manufacturing [

11]. However, EVs are currently unavailable for purchase in the Kingdom, although they can be imported, and there has been scant research into how end-users perceive them, or the challenges to their widespread adoption. The need for such research has recently become more pressing. In May 2022, Lucid Motors, a US EV manufacturer, announced that it will begin constructing manufacturing facilities in the Kingdom, with a capacity of 155,000 electric vehicles [

12]. As part of the deal involves the Saudi government committing to purchase 100,000 vehicles over a ten-year period, there is an increasingly urgent need to understand how potential users in the country view EVs and the nature of the barriers to their widespread adoption. In exploring these issues and identifying both general barriers (applicable in most contexts) and local barriers (applicable in similar cultural and geographical contexts), this study will inform the development of public policy to encourage drivers to adopt EVs, thereby serving the strategic imperatives of sustainable transport and development and promoting the related social and environmental values.

In order to achieve this aim, the paper addresses the following research questions to explore the relationship between potential users’ perceptions of EVs and the barriers to their widespread adoption:

RQ1: What are the salient characteristics of EVs and what is their potential for strengthening EV acceptance?

RQ2: To what extent are EVs perceived as economically, socially, and environmentally beneficial compared to ICEVs in Saudi Arabia?

RQ3: What are the main barriers to widespread EV adoption, which ones are regarded as most significant by potential users, and are they nationally, regionally, or internationally applicable?

5. Discussion

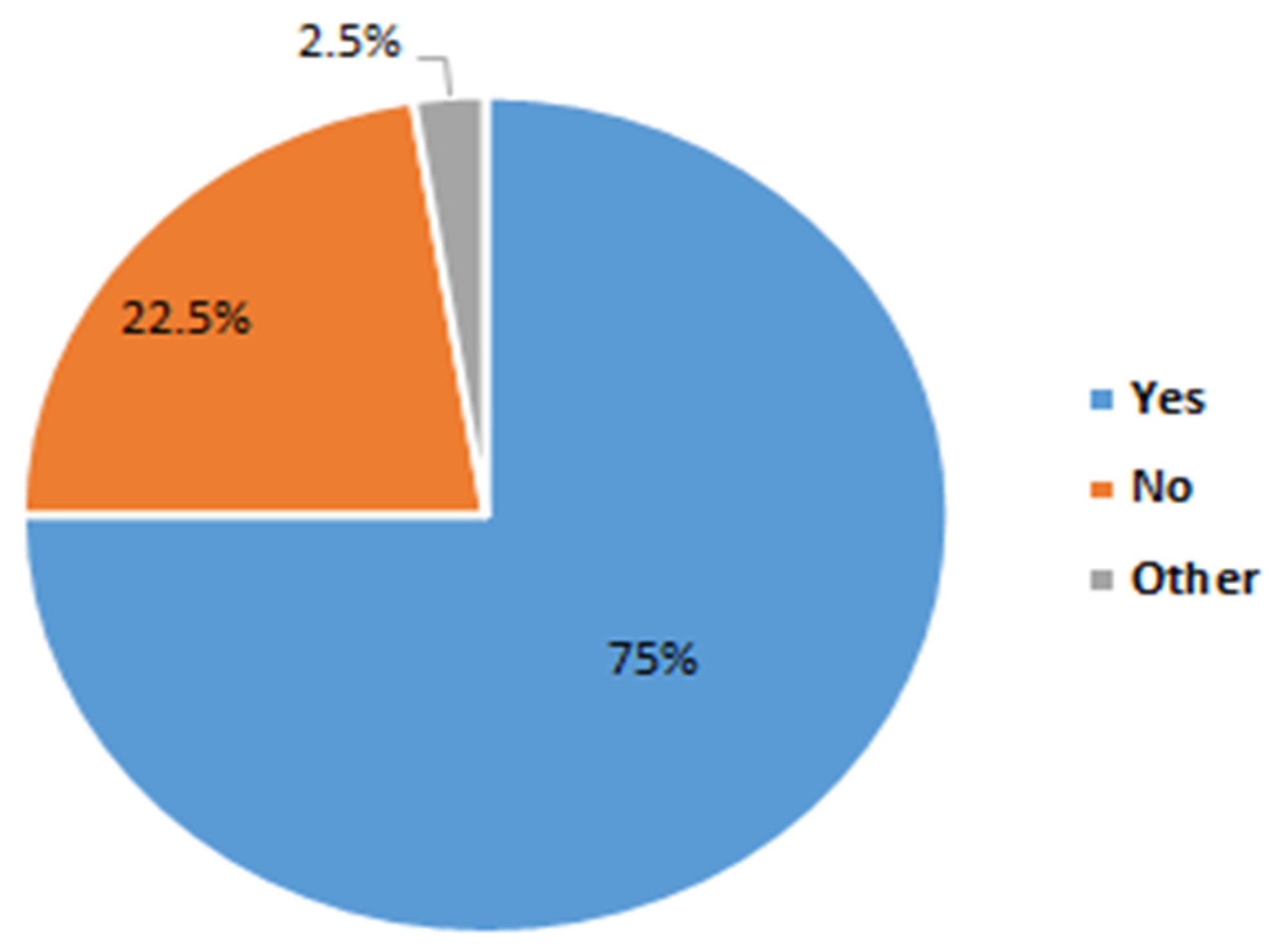

The thematic framework developed by combining the results of the quantitative aspects of the research and the qualitative analysis provides a model of how potential users in Saudi Arabia perceive the barriers associated with EVs and their relative importance (See

Figure 8).

Infrastructure is an essential prerequisite for the adoption of EVs, and two of the barriers in this category (charging stations and maintenance provision) would apply in any national context; however, concerns around the additional load EVs place on the grid are particular to Saudi Arabia, and to other hot countries where the capacity to generate electricity sometimes fails to meet rising demand. The top ranking of charging stations reflects consumers’ concerns that EVs may not be practicable across the large territory of Saudi Arabia, echoing anxieties over BEVs’ relatively limited range, long charging times, and the time it will take to replace petrol stations with a charging network [

118]. EVs’ dependence on emerging technologies makes consumers unlikely to support their adoption in the absence of appropriate infrastructure, and the significant demand among respondents for both urban and rural charging stations, consistent with the existing literature [

119], suggests that building an extensive charging network would be a significant early step in accelerating the deployment of EVs across all parts of the country. Furthermore, it seems that a variety of charging infrastructure, including rapid chargers for drivers who travel more than 100 km per day, is needed. However, clear policy is needed to identify where responsibility for creating infrastructure lies, since EV manufacturers tend to believe that the government should be fully responsible for developing charging stations and repair maintenance facilities, while governments believe that the industry should also play a part [

33]. Thus, adopting EVs requires collaboration from both private and government sectors to build suitable infrastructure, and the private sector needs to be encouraged through the provision of competitive investments and grants.

Consumers’ concerns regarding maintenance, evidenced both quantitatively and qualitatively, are perhaps unsurprising, given that EV deployment in Saudi Arabia is at an early stage, and as the technology becomes more widespread, these are likely to reduce over time. However, in a hot country, such as the KSA, the demand EVs place on the grid is likely to pose a significant barrier in the longer term, and stakeholders must find alternative ways to mitigate the risk of grid overloading, such as utilising renewable energy resources, managing charging times, and implementing effective policies and strategies. Existing research warns that connecting EVs to the power grid may result in higher short-circuit currents, voltage fluctuation, demand surges, and reduced equipment lifespan [

120], and the national grid must be upgraded in order to meet this new demand [

121]. In addition, higher electricity consumption also entails increases in GHG emissions if solar, wind, wave, or other sustainable generation alternatives are too costly or cannot satisfy demand, so policy makers must consider energy generation and renewable energy usage when developing infrastructure to support EVs. In this regard, it is significant to note that potential EV users in Saudi Arabia have identified the need for renewable sources of electricity as a significant factor affecting their willingness to adopt EVs [

7], and resource diversification in this way would be sensible for both load profile and for EV users. While the increase in demand on the grid will occur in any country in which EVs are adopted, this is a particular concern in Saudi Arabia, and in other hot countries, where demand for air conditioning places significant strains on the existing energy supply.

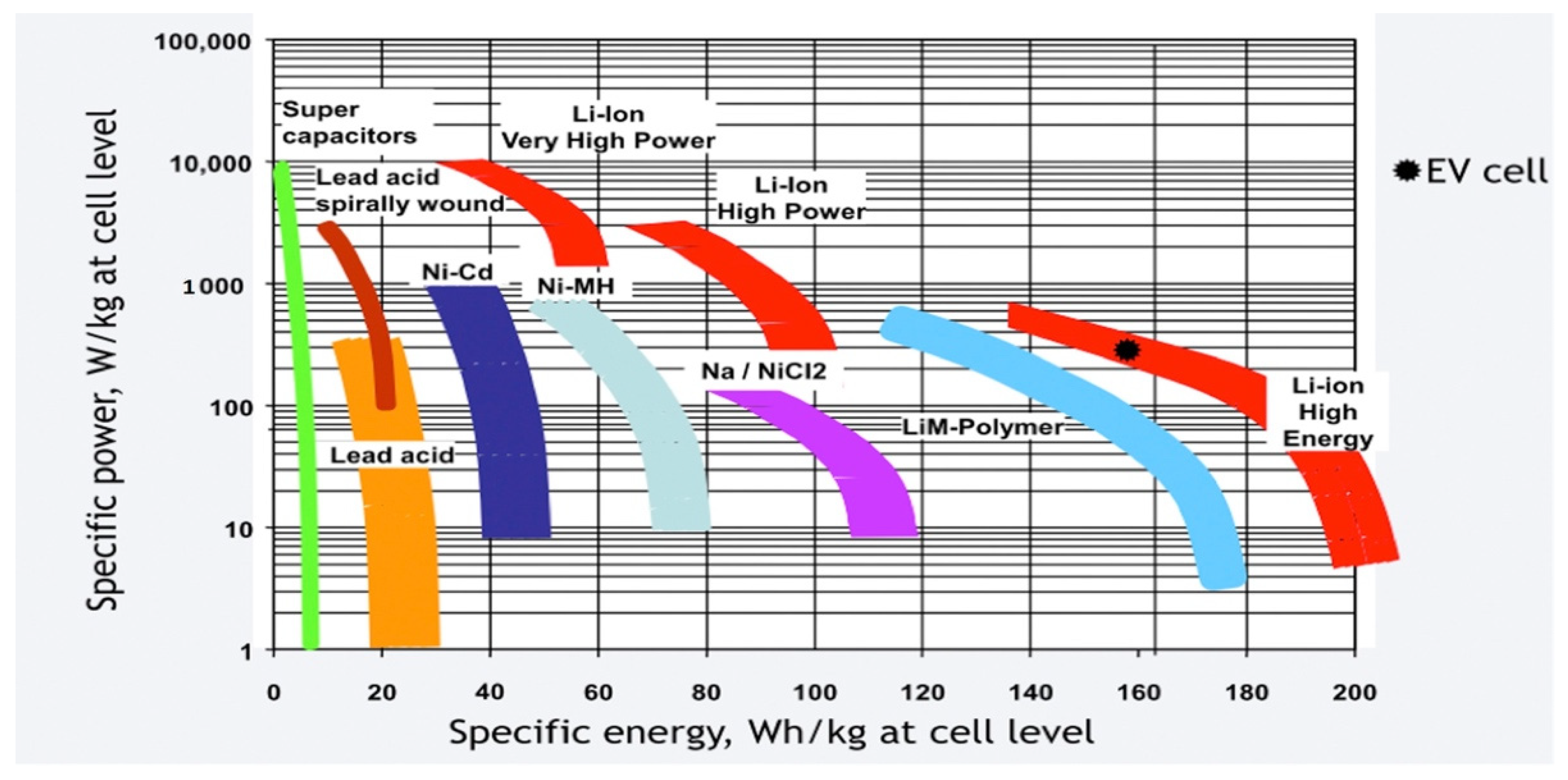

Participants were found to rate the performance dimension, comprising limited range, reliability, battery lifespan, charging duration, safety, and weather conditions and terrains as particularly important. Doubts about performance are evident in both sets of data, with consumers concerned that EVs may not be reliable in the country’s extreme climatic and geographical conditions, and stakeholders, including manufacturers and lawmakers, must take account of these if EVs are to be more widely adopted. Furthermore, to satisfy customer demand for EVs in a country such as India, EV motors should be made more durable and cost-effective for easy maintenance and repair [

6]. Concerns are clear in the qualitative findings, which demonstrate anxieties over BEVs’ relatively limited range, battery life, long charging times and safety and reliability. These are reflected in the literature, with limited ranges and long charging times recognised as the two largest barriers to consumer acceptance of EVs in the passenger vehicle market [

122]. The issue of the reliability and safety of EV components is also regarded as an important concern [

123], and the limited battery life imposes a significant financial burden on EV users, as well as affecting EV performance, and is also considered as a significant barrier [

124]. While the risk of traffic accidents is an issue in any context, the climate in the KSA raises concerns about the exposure of batteries to high temperatures and the potential fire risk of lithium ion batteries. Although the risk of an electrical shock from a vehicle is very low, because the components and cables are usually well-insulated and covered [

125], concerns about the effectiveness of EVs across the various terrains and hot weather conditions in the KSA persist. As the US tests in the desert region of Arizona have indicated that the driving range can fall by 29% when average daily temperatures reach 41 °C [

126], more extensive testing in desert conditions by battery and EV manufacturers, such as Lucid Motors, are required to reassure consumers that EVs are a viable option in the Kingdom.

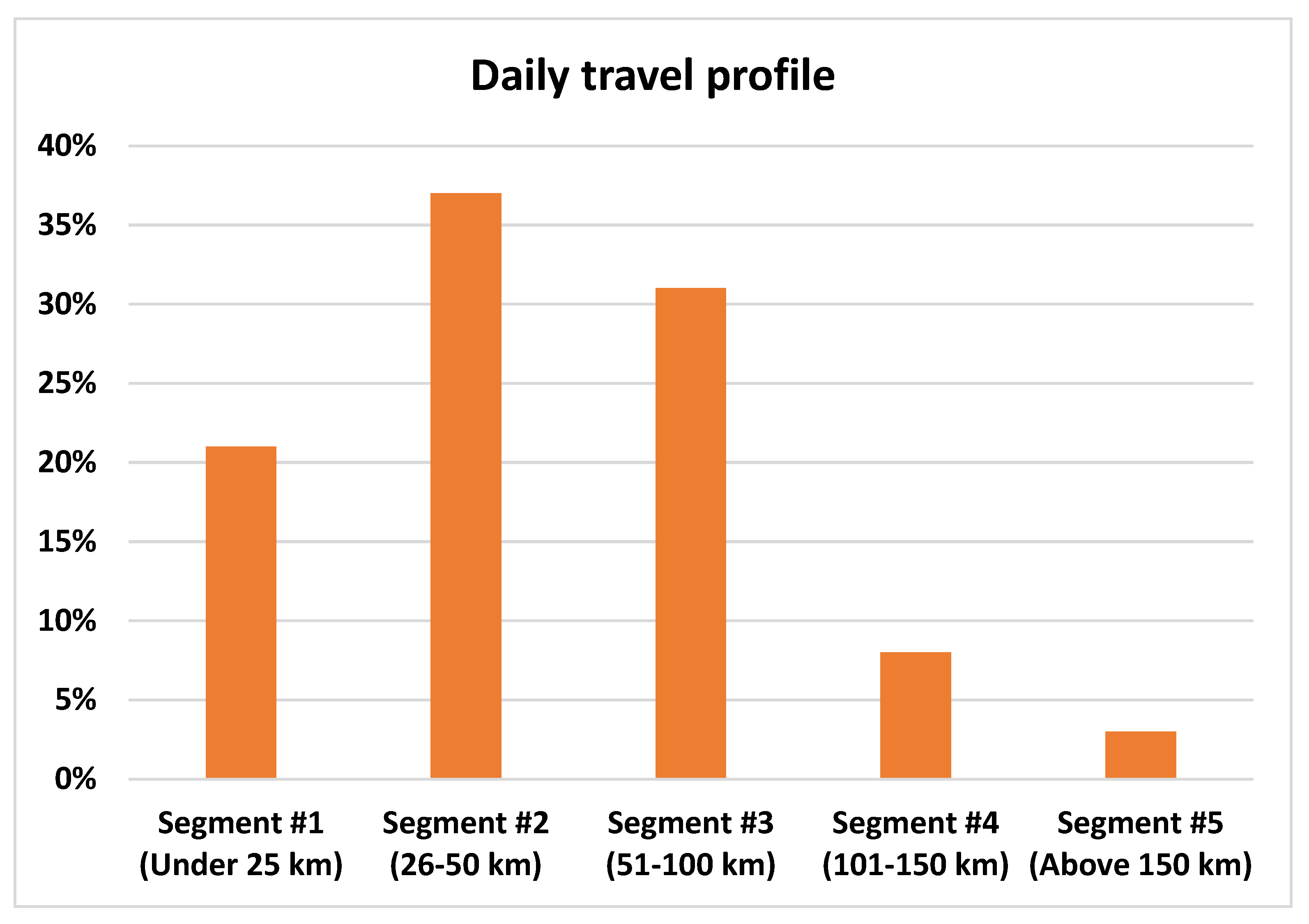

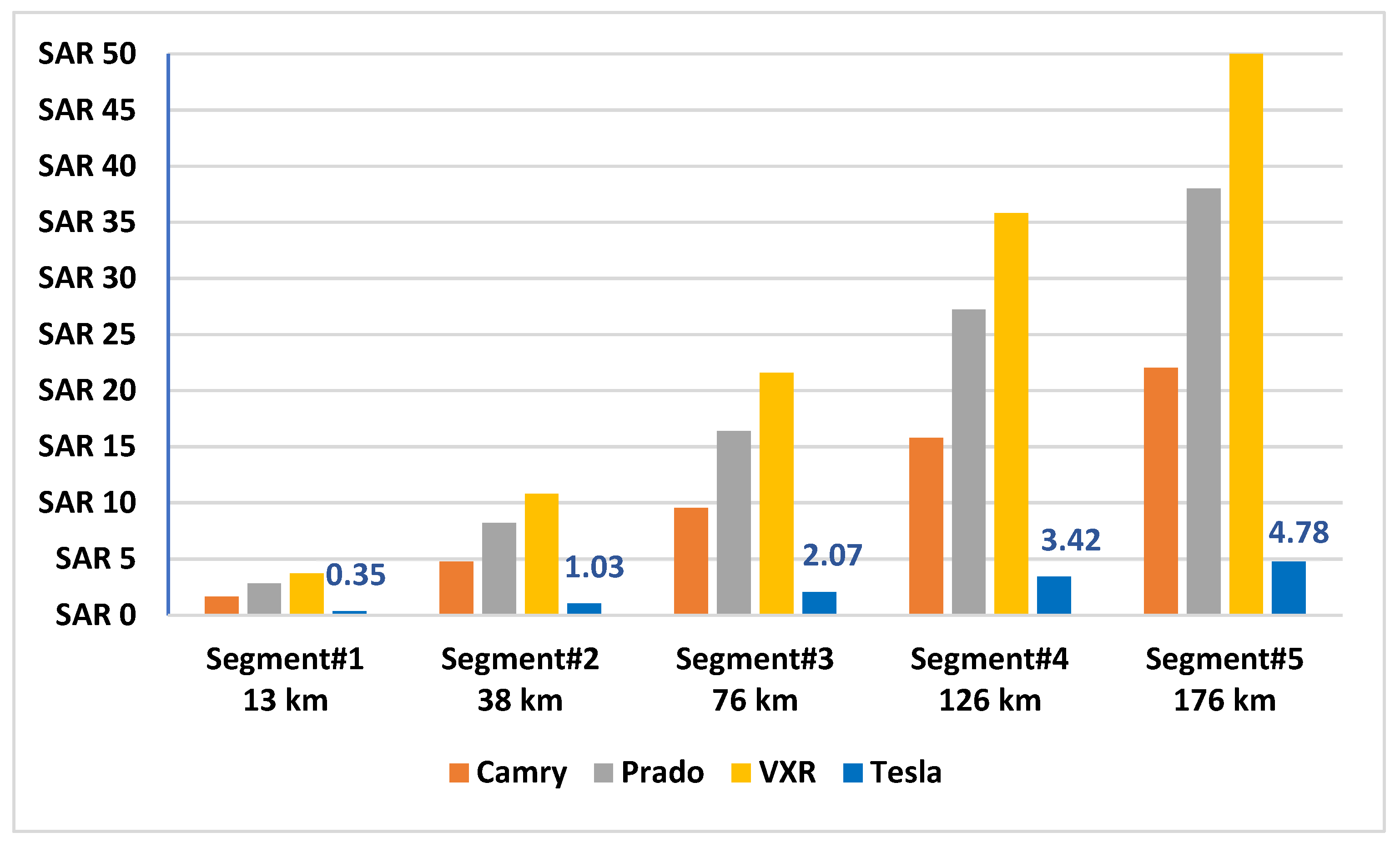

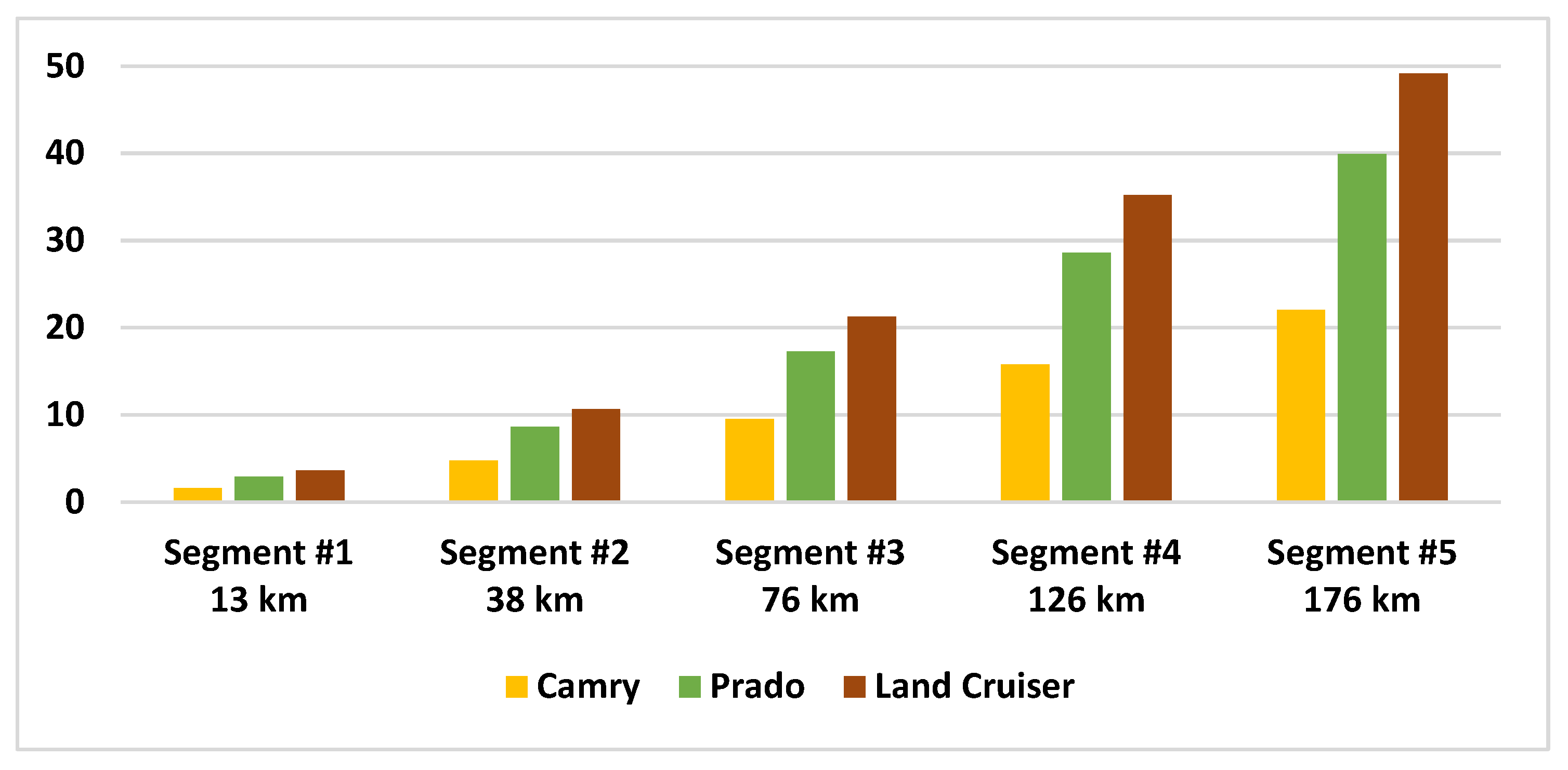

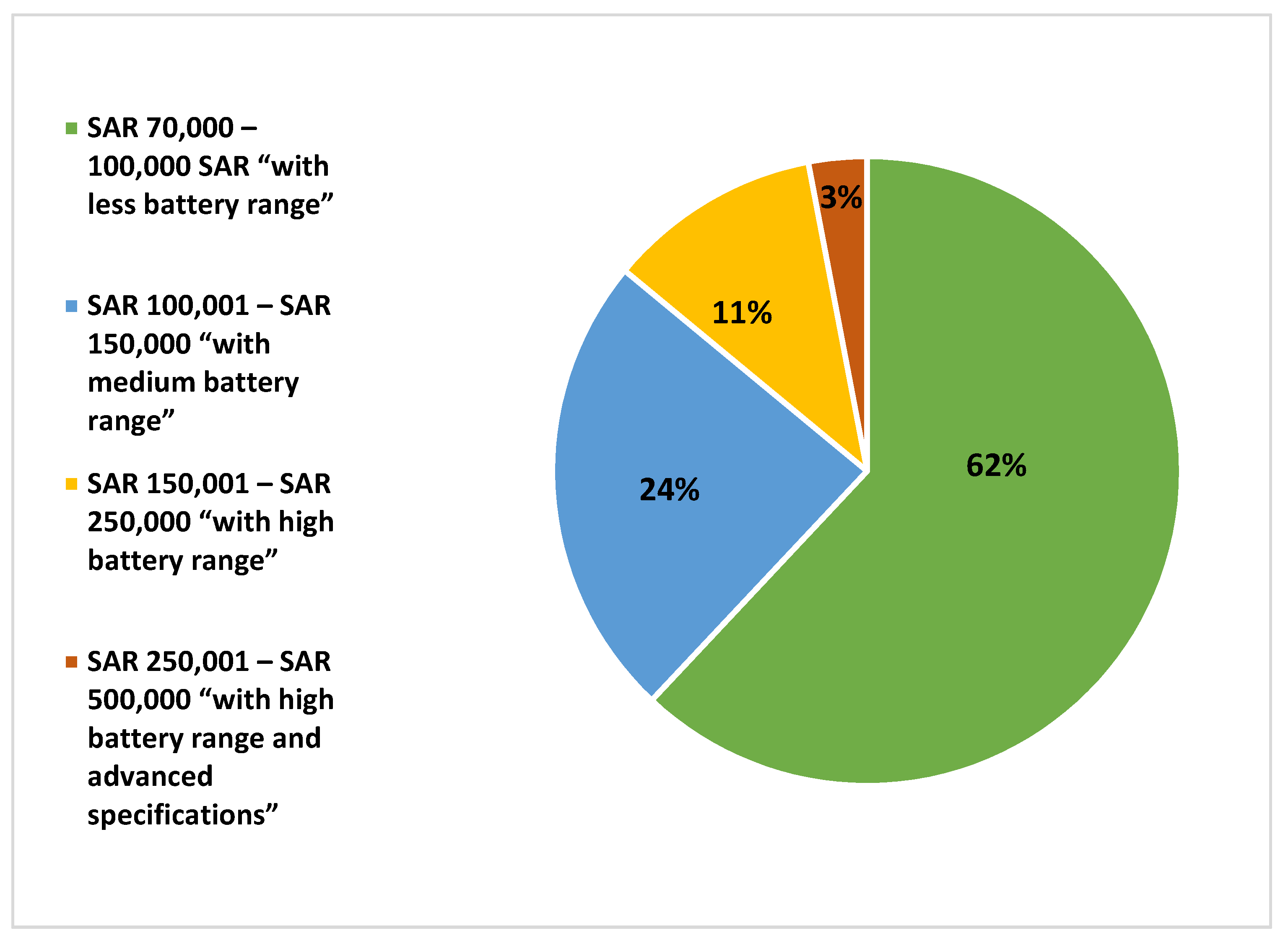

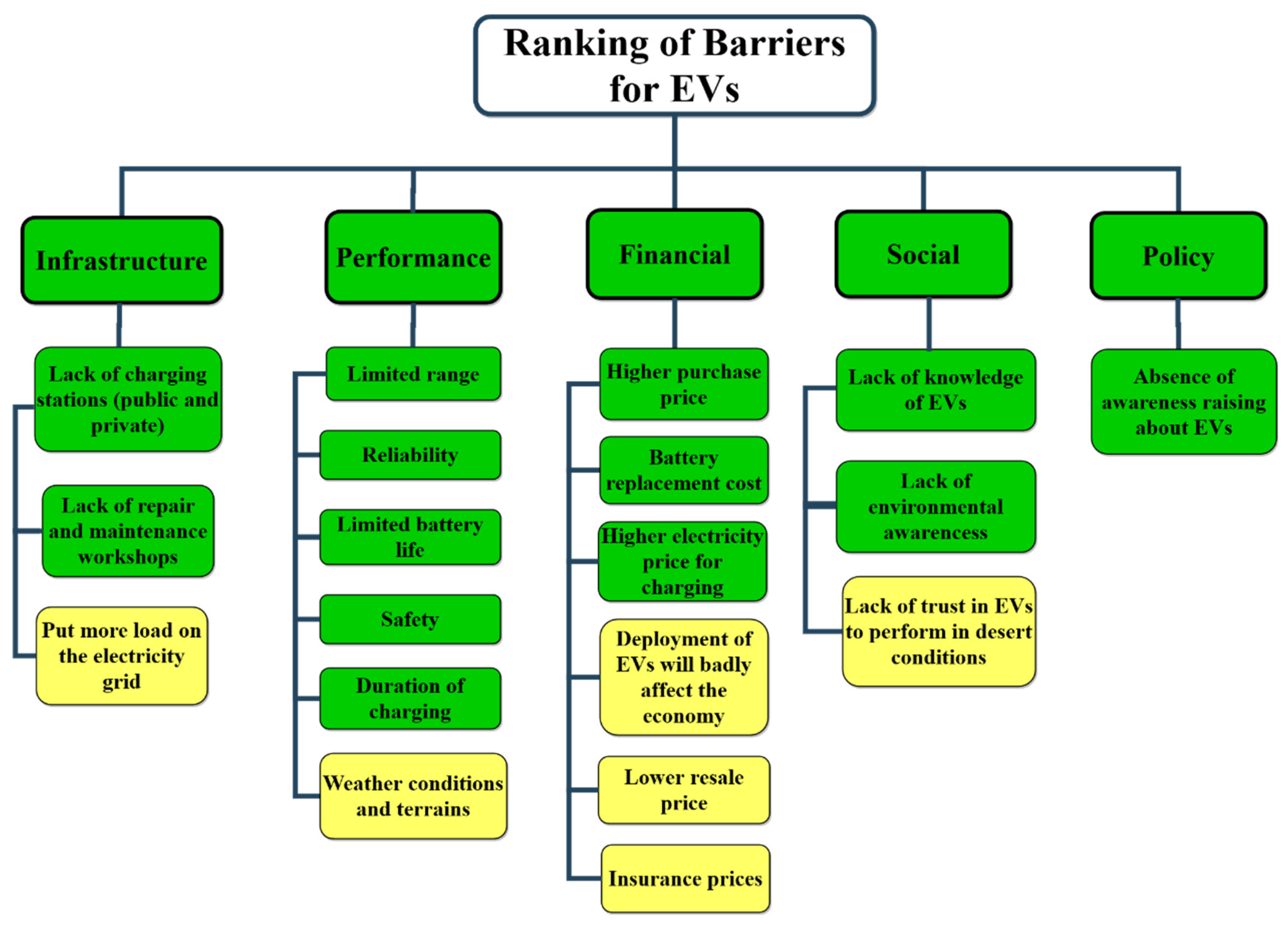

The most significant barrier in the financial category is EVs’ high purchase price, principally because batteries are expensive. However, low running costs (e.g., fuel and maintenance) make the total cost of EV ownership more competitive, especially by comparison with high-end ICEVs over longer distances (See

Figure 9), and costs are expected to decline significantly in the coming decade as batteries become much cheaper [

127]. The concerns expressed by some participants about the higher cost of electricity may be due to lack of knowledge about how much cheaper it is to charge an EV than to fill up an ICEV with petrol, allied to the fact that Saudi citizens now pay much more for home electricity (+260%) since subsidies were reduced [

76]. Participants concerns about maintenance costs are more firmly grounded though, reflecting the fact that brand leaders, such as Mercedes and BMW, are particularly expensive to maintain in Saudi Arabia.

Both the qualitative and quantitative data reflect consumer concerns about the possible impact of EV adoption on the economy of Saudi Arabia, a country which is a major oil producer. This is a novel concern in the context of EVs; however, evidence from the Saudi Energy Efficiency Center [

75] suggests that it may be misplaced. The KSA’s transportation industry currently consumes around 21% of the country’s total energy, with light duty cars accounting for 52% of the sector, and energy demand for transportation is anticipated to treble by 2030 [

75]; therefore, EVs are unlikely to decrease oil production but rather help to meet rising energy demand. In addition, EVs require oil for raw materials and manufacture, and it is difficult to predict when this might no longer be the case. Finally, given the recent dramatic increases in global crude oil prices, reaching USD 128 per barrel in March 2022 [

128], deploying EVs at a rate that is manageable in terms of energy consumption would mean more Saudi oil could be sold on the international market, as opposed to being supplied at low rates domestically, thereby helping the country’s economy rather than damaging it.

The last two barriers in relation to performance are the lower resale and insurance prices. Multiple factors, including mileage, modification, brand and model, condition, and cost of maintenance can impact the resale value of a vehicle, but battery replacement cost is unique to EVs and means they tend to lose value more quickly than ICEVs [

129]. In addition, according to [

6,

130], in the early stages of EV adoption, resale values are unclear, making users of EVs more uncertain about this than with ICEVs. In terms of insurance prices, participants may be concerned that the expensive batteries in EVs will affect the insurance prices; however, research suggests that, on average, EV insurance prices are about USD 200 less per year than for a similar ICEV [

131].

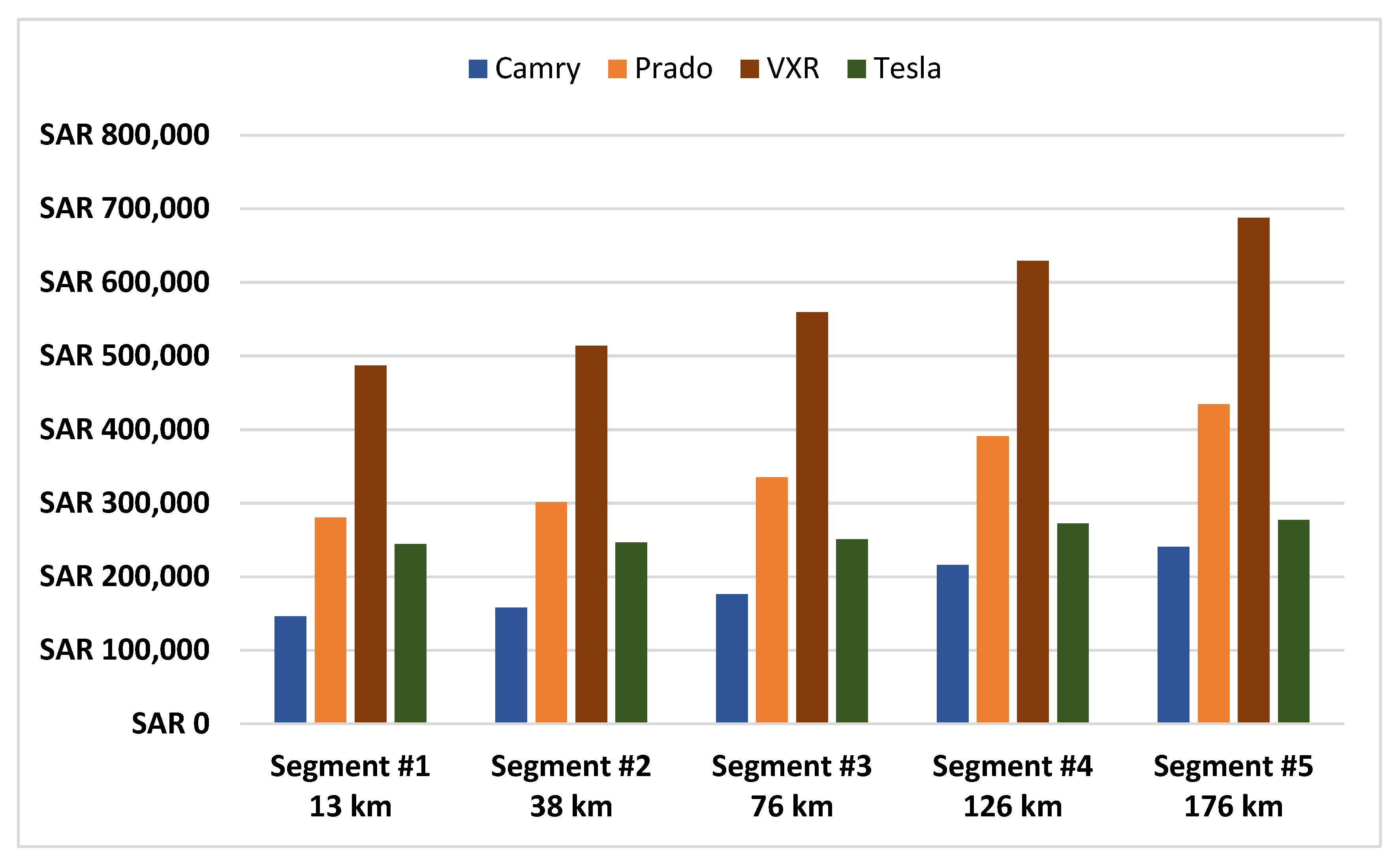

The social dimension is often ignored when sociotechnical systems, such as EVs, are designed [

132], yet the findings of this study suggest that this is a significant barrier in the Saudi context. Part of the difficulty related to systems engineering lies in separating a system from its context, especially one which is designed for general consumers, who may be ignorant of its technical and environmental capabilities [

133,

134]. The qualitative data indicate that lack of consumer awareness about EVs may impact purchasing decisions, and this finding is supported in the literature [

135]. While it is expected that participants in a country that has not yet deployed EVs will have less practical knowledge about them, this also indicates a lack of understanding about the sector as a whole and the benefits of EVs, both economically and environmentally, among potential users. The lack of trust in EVs in desert climates also suggests a lack of awareness, and EV manufacturers in the Saudi market need to enhance their marketing and educational efforts in order to achieve market penetration. The very fact that respondents recognise environmental sustainability as a concern in relation to EVs indicates that consumers in the KSA are becoming more environmentally aware; however, despite this, they placed relatively little importance on environmental issues in relation to EVs. This suggests that Saudi consumers may also be poorly informed about the advantages of EVs, including their potential to reduce GHG emissions. In this respect, suggesting that environmental awareness significantly influenced older users [

7]. There is thus a need for more education regarding the environmental advantages of green transport, especially among younger drivers.

EV initiatives should include awareness-raising on environmental challenges and such knowledge should be disseminated from an early age through the government’s education policy. However, there are legitimate concerns about the environmental impact of EVs during their lifetime which should be addressed, especially in terms of reducing car usage and recycling. The operating phase of mobility has the greatest environmental impact, regardless of whether an ICEV or an EV is used [

136], and greater investment in public transportation would reduce the number of car journeys taken. In addition, while LIBs are regarded as environmentally friendly, with a lower carbon footprint than other battery types, notably during the raw materials processing, manufacturing, and usage stages [

137], waste in urban centres remains a critical issue, and a much greater understanding of all aspects of the EVs’ real-life cycle is required in order to conclusively identify them as environmentally beneficial [

138].

The issue of renewable energy use and EVs is of particular interest in the Saudi context. The qualitative data show that consumers are aware of the need for alternative energy resources to be utilized to avoid overloading the grid. This concern may be explained by recent public energy awareness campaigns, and drivers wishing to ensure that future shortages will not limit their car use, hence the suggestion to employ alternative resources. Were renewable sources to be utilized, V2G technology could help to ease fluctuations and peak load shaving because parked EVs could constitute a resource during peak demand. However, concerns about V2G technology, including fears about potential reductions in battery life due to the effect of high temperatures when batteries are charged and discharged, should also be examined and addressed. In addition, financial incentives, infrastructure availability, and possible fuel-related savings are anticipated to be crucial factors influencing the adoption of EV [

33], and these also have a social dimension in terms of their ability to change consumer behaviour. However, it is currently unclear how these can be deployed most effectively, and this makes it essential to investigate the social dimension further so as to promote understanding of the social features and challenges of the use and adoption of EVs.

Finally, the policy dimension, including regulation and governmental initiatives, is a significant factor, with policy on tax and infrastructure also seen as important in promoting EV adoption, alongside financial support for EV purchases and R&D projects [

139]. In this context, the Lucid Motors proposal is consistent with the Saudi government’s Vision 2030 aim of technology localization. While Vision 2030 has a renewable energy component, SASO is responsible for technical regulation, and it has recently set out the minimum health and safety standards for EV consumers [

140], marking a significant step towards the adoption of EVs in the country. However, the findings of this study suggest that a broader range of policy instruments, based on specific public policy goals, will be required. These should address technical EV requirements and regulations, but also improve awareness by providing accurate information on related issues, such as safety standards, guides for using and charging EVs, how to import them from abroad, how to perform maintenance in the absence of local repair centres, how to avoid the dangers of accidents, as well as guidance for firefighting personnel and others who may have to deal with incidents involving EVs.

6. Conclusions

EVs have the potential to have a substantially less negative impact on global climate than ICEVs, and governments around the world are beginning to take steps to support their adoption. With the recent deal with Lucid Motors, the Saudi government is taking a major step forward in this respect, and other initiatives in support of the low-carbon ambitions set out in Vision 2030 are also beginning to be operationalised. However, significant barriers to the widespread adoption of EVs in the KSA need to be overcome if these ambitions are to be realised. This study has examined public perceptions of EVs in the Kingdom, identified the barriers to their adoption, and created a framework which ranks them in order of their importance to potential users. The barriers have also been classified as either infrastructure, performance, financial, social, or policy concerns, without negating the connections between them. While many of these barriers are applicable internationally, others are particularly significant within Saudi Arabia, and other developing countries which share similar geographic and climatic contexts. For example, while the lack of charging infrastructure is common to many countries, the need to develop the grid infrastructure to support the additional demands of EVs is particular to a developing country with a hot climate in which the existing power systems sometimes struggles to meet demand, especially during the summer months.

Indeed, the extreme climate in the KSA and the varied terrain, encompassing both large desert areas and mountainous regions, give rise to a number of barriers, including concerns about the safety and effectiveness of batteries at high temperatures, and doubts about the overall ability of EVs to perform effectively in desert conditions. Manufacturers, such as Lucid Motors, would be advised to take steps to address these concerns if they wish to achieve market penetration in Saudi Arabia and in other countries in the region. Greater awareness raising campaigns by both manufacturers and governments are also required as the study suggests that the public do not yet fully appreciate the economic and environmental benefits of EVs, with misplaced concerns about charging costs and possible damage to the Saudi economy continuing to persist. By contrast, evidence suggests that the widespread adoption of EVs could actually benefit the economy, especially if they are powered by renewable sources of electricity, freeing up the country’s oil resources for sale at a higher price on the international market. Such a switch would also enhance EVs’ environmental credentials and reduce some of the pressures on the grid. The use of V2G technology would also help with this, but it would require both advances in charging technology and the provision of sufficient charging points to allow consumers to exchange energy freely with the grid.

Although the aims set out in Vision 2030 are beginning to be realised, Saudi Arabia is still at an early stage of EV adoption, and policy makers have not yet undertaken significant action to encourage sales. The study found that there is variation in the cost of the different EVs makes, for example, the Tesla Model 3 is up to 40% more expensive to own than a Toyota Camry, indicating that, in the absence of government subsidies or financial incentives, owning EVs may be much more expensive than owning small-sized internal combustion engine-based vehicles (ICEVs). The hope is that these findings will assist in promoting EV adoption in the country, and the wider region, by providing guidance to stakeholders, including policymakers and EV manufacturers. While some of the factors identified are country-specific, others have regional or global relevance, and this study’s results could be generalized to other contexts with similar climatic, geographic, and economic conditions, notably other Gulf states and other oil-producing nations. The proposed general framework could, however, also be used to identify and rank equivalent barriers in other regions or countries, if the analysis was customized accordingly. For example, purchase price might be seen as relatively unimportant in contexts where subsidy or other public policy support is offered, and battery cost and availability may matter less in countries with local manufacturing facilities.

The results of this study suggest that the widespread adoption of EVs in Saudi Arabia could help the country to achieve its emissions reduction goals, especially if steps are taken to develop more sustainable production processes and cleaner electricity grid mixes. This would both reduce the cost of EV charging and limit GHG emissions. While further research with the small number of drivers in Saudi Arabia who currently use EVs may reveal additional barriers, addressing the obstacles identified here would support the ambitions expressed in Vision 2030 and provide a model for EV adoption in major oil-producing states.