1. Introduction

There are numerous scientific and technical fields in which it is important to know the structure, composition, and type of the soil. For example, in geology, by knowing the structure, composition, and types of soil, it is possible to model, analyze, and understand the processes of how the earth is formed. Knowing the structure and composition of the soil enables accurate techno-economic calculations of profitability and technical requirements for mining the ore of interest. Also, knowledge of the above soil characteristics is important for creating models that analyze soil–masonry interaction. With such models, it is possible to carry out sensitivity studies and probabilistic analyses of the behaviour of different construction facilities during the movement of soil layers and earthquakes. In electrical engineering, the electrical characteristics of grounding conductors that are buried in the soil depend on the electrical resistivity and structure of the soil. The resistivity of the soil depends on the type of soil, composition, soil moisture, and temperature. For these reasons, numerous methods for determining the composition, type, and structure of soil have been developed. Among the electrical methods used for this purpose, the most well-known methods are those based on the use of ground penetrating (probing) radar [

1,

2] and galvanic methods based on soil resistivity measurement [

2,

3,

4,

5]. In this paper, we focus on galvanic methods for determining soil structure, or more precisely, on the Wenner method [

2,

3,

4,

5]. For simpler soil structures such as two-layered soil, the interpretation of measurement data obtained by Wenner’s method is simple [

5]. However, even more complex soil structures can significantly complicate the interpretation of measurement data. Also, the interpretation of data can be further complicated by the presence of noise in the measurement result, which can be caused by electromagnetic coupling with high voltage overhead transmission lines [

6]. In all such cases, and other complex electromagnetic problems, the simulation results obtained using the finite element method (FEM) are very helpful [

7,

8,

9]. To demonstrate the above, the paper presents the modelling of the Wenner method and soil using the FEM-based Ansys Electromagnetics Suite v22.1 software [

10]. The presented procedure and modelling methodology are similar for other FEM-based software such as COMSOL Multiphysics 6.3 [

11]. For this purpose, a common two-layer soil model was chosen. For more advanced modelling and analysis, the two-layer soil model is extended by adding local heterogeneity in the soil. The local heterogeneity is in the shape of a cylinder whose radius corresponds to concrete pipes buried in the ground. The influence of local soil heterogeneity, which can be expected during practical measurements, was analyzed.

2. Theoretical Background

Because of the importance of galvanic measurement methods for determining soil structure and resistivity, galvanic soil resistivity measurement techniques are described in detail in IEEE standard (Std) 81-1983 [

3] and IEEE Std 80-2000 [

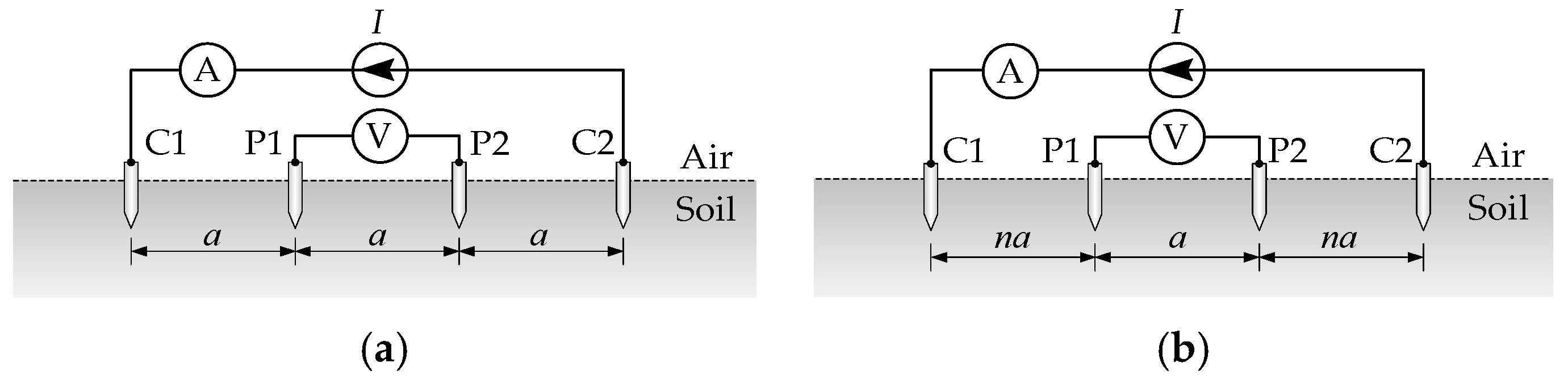

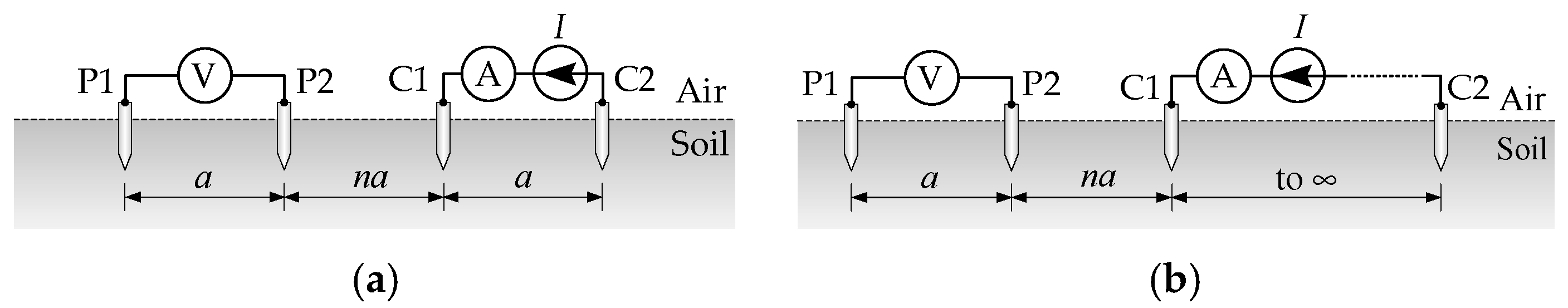

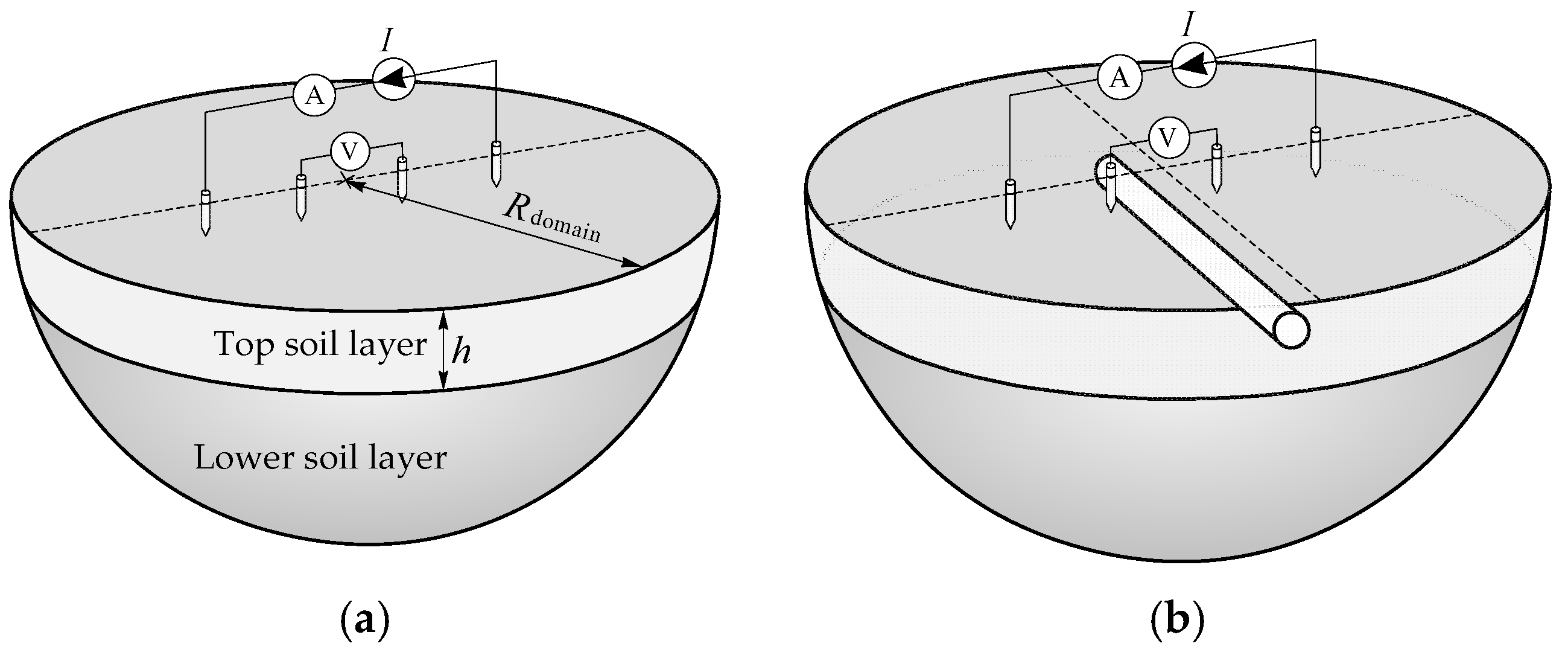

4]. The most common galvanic techniques are: the Wenner method, the Schlumber method, the dipole–dipole method, and the three-electrode method (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 compilation from [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]).

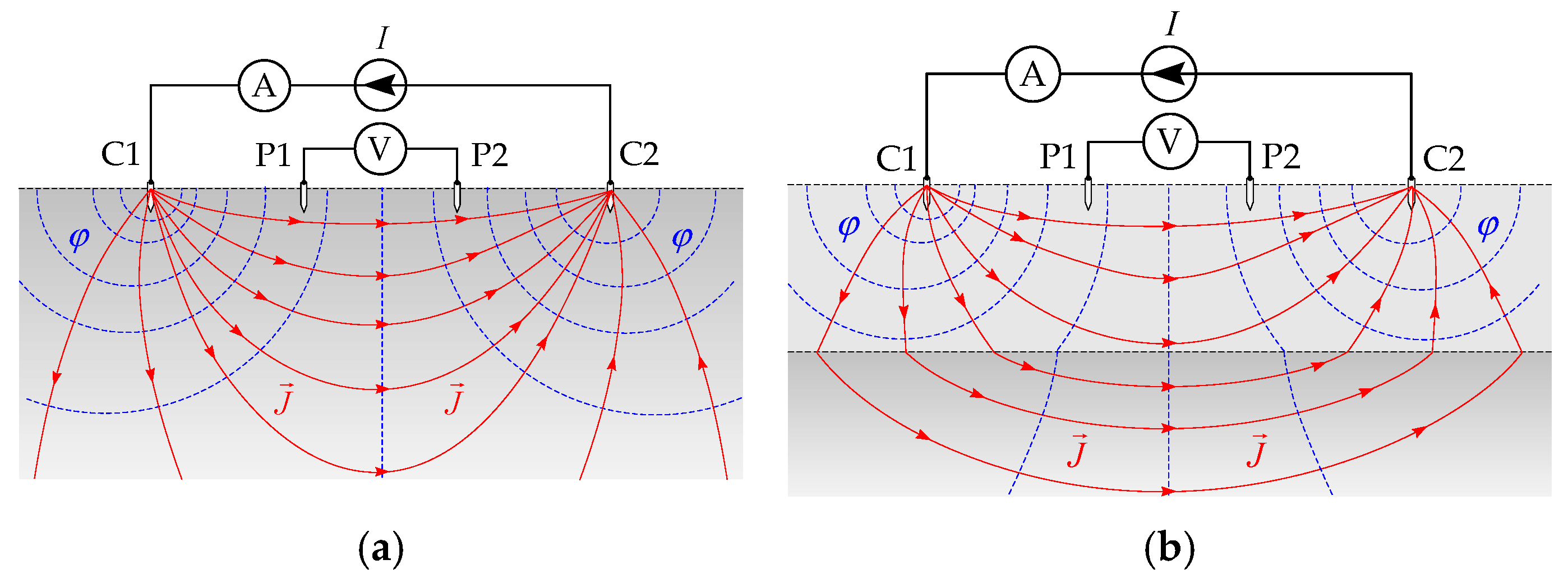

Wenner’s measuring setup consists of a current source of known current, wiring, a voltmeter, and four electrodes that are partly buried in the ground. According to IEEE Std 356-2001 [

2], electrodes should penetrate into the soil at least 10 cm to ensure adequate contact. With the help of current electrodes (C1 and C2), current is injected into the conductive soil. Both direct current and alternating current sources can be used. If alternating current sources are used, they are extremely low frequency (below 50 Hz) [

2]. In this process, a certain spatial distribution of the current field and the scalar electric potential in the soil is established (

Figure 3a,b [

12]). Both the spatial distribution of the current field and the scalar electric potential are influenced by the soil structures and soil resistivity. From the measurement of the potential at the soil surface at the location of potential electrodes P1 and P2, the spatial distribution of soil resistivity can be determined. For this purpose, a set of measurements at different electrode spacing is required. When the distance between the current electrodes is small, the greater part of the current injected into the soil flows along the upper layer of the soil along the soil–air boundary (

Figure 3a,b [

12]). For this reason, in multi-layered soil, the measured resistivity value will be close to the resistivity value of the upper soil layer (

Figure 3b). The greater the distance between the current electrodes, the greater the proportion of the injected current that penetrates deeper into the soil (

Figure 3b). For this reason, the measured resistivity value will be close to the resistivity value of the lower layer.

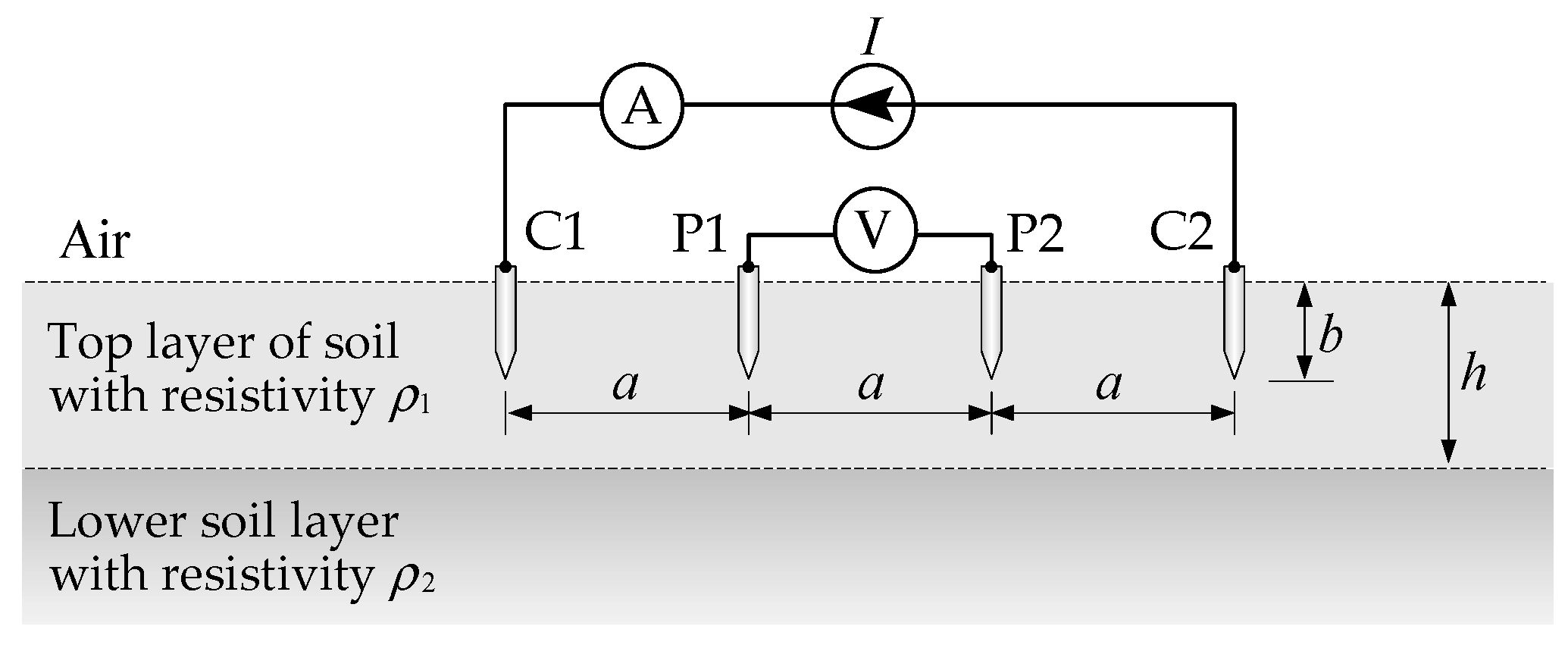

Given that the upper and lower soil layers simultaneously affect the measured result, based on multiple measurements at different electrode distances and the corresponding soil model, it is possible to correctly interpret the measurement results. That is, to determine the thickness of the top layer and the resistivity of individual soil layers. In general, it is possible to construct a model describing the apparent resistivity for an arbitrary number of soil layers. However, with the increase in the number of layers, the complexity of the model increases drastically, and data interpretation becomes more difficult. For this reason, soil is usually modelled with a small number of layers. In practice, the use of a two-layer soil model prevails (

Figure 4).

When the distance between adjacent electrodes is much greater than the buried part of the electrodes (

), for the Wenner method, apparent resistivity

of the soil is given by expression [

2,

3,

4,

5]:

where

is the distance between adjacent electrodes in m,

is the measured voltage,

is the measured current.

By applying the method of images [

5,

13] to the two-layer soil model, it is possible to obtain an analytical expression for apparent resistivity for the Wenner method [

2,

3,

4,

5]:

where

is the apparent resistivity of the soil in Ω∙m,

is the distance between adjacent electrodes in m,

is upper layer height in m,

is an integer,

is a large integer number, theoretically infinite, but for practical calculations, it is enough to take a number greater than 20. Reflection coefficient (

) is given by the expression [

2,

3,

4,

5]:

where

is upper layer soil resistivity,

is lower-layer soil resistivity.

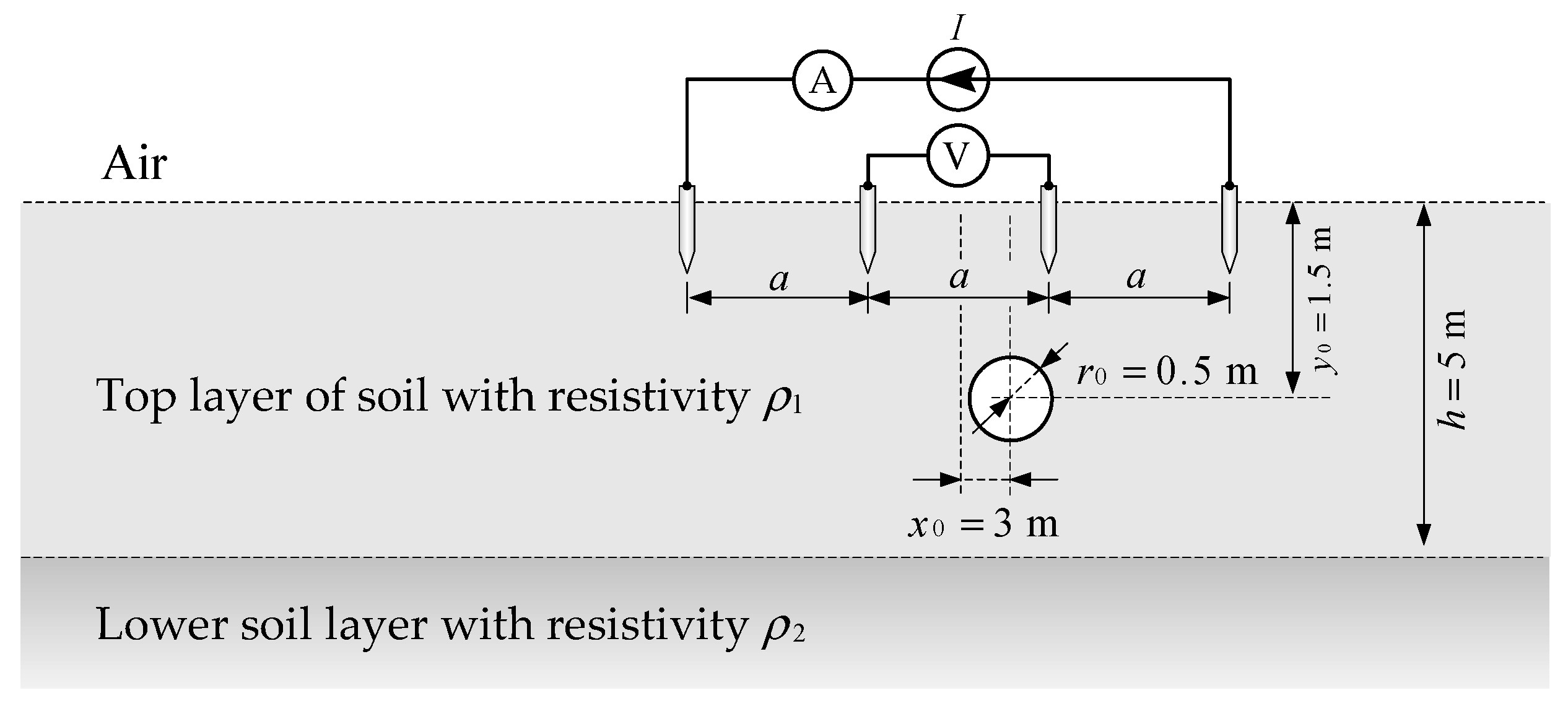

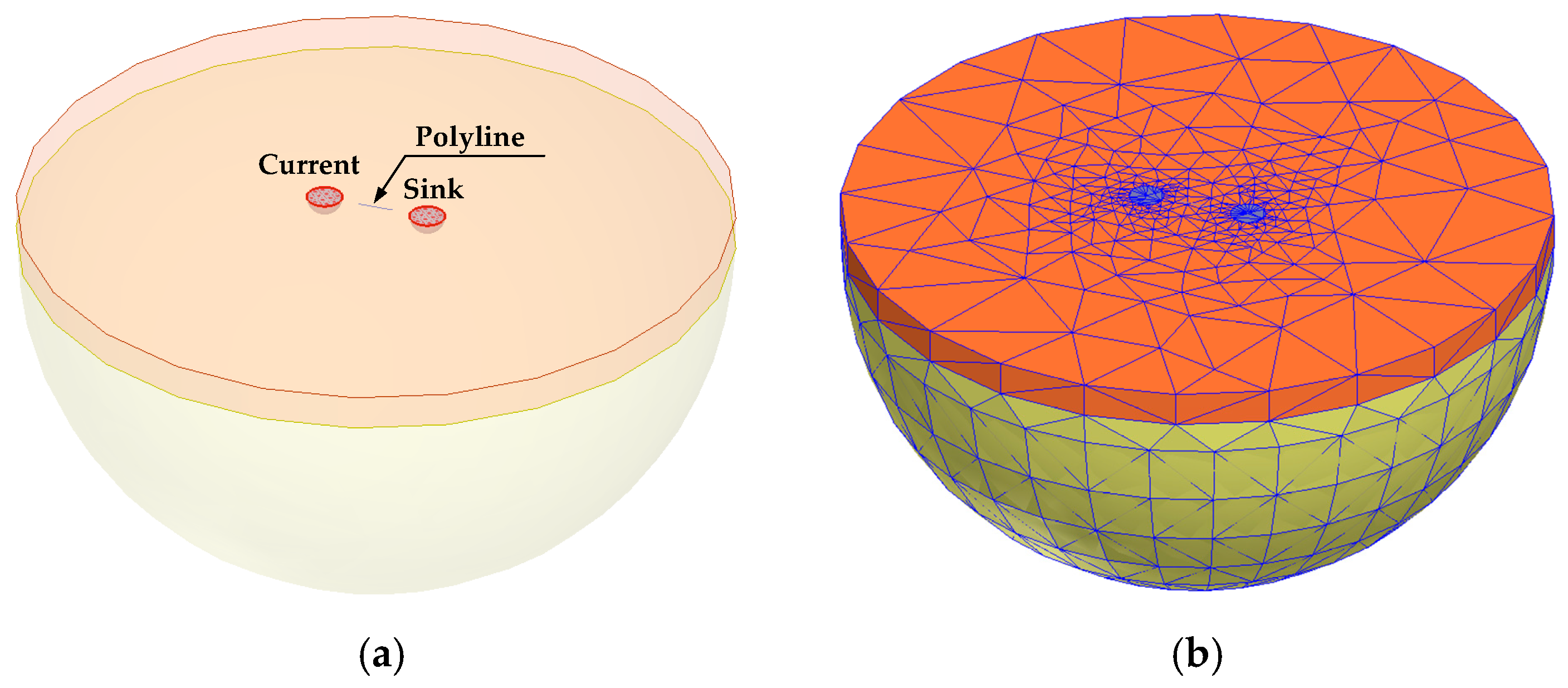

3. Soil and Wenner Array Modelling: FEM Approach

Electromagnetic (EM) problems, for example, as described in this paper (soil and Wenner array), can be described with integral or differential equations. The type of numerical method applied to solve the resulting system of equations depends on the choice of description of the EM problem. If the EM problem is described with integral equations, then the boundary element method (BEM) is used to solve the resulting system of equations. If the EM problem is described by differential equations, then the finite element method (FEM) is typically used to solve the resulting system of equations. Among the more popular (well-known) software packages that use the FEM are Ansys [

10] and COMSOL [

11]. In this paper, the soil and Wenner array were modelled in the Ansys software. The Ansys software has inherent features that make it particularly suitable for simulating and analyzing galvanic vertical electrical sounding techniques. Among many, the ease of modelling heterogeneous soil, both in terms of structure and electrical parameters, stands out. At the same time, it is easy to model different electrode arrays, and automate the calculation process using the parameter sweep option. These benefits were used in the example of numerical calculation of the apparent resistance of a two-layer soil using the Wenner method. Given that in the FEM approach infinite and semi-infinite space needs to be represented by a space of finite dimensions, the two-layer soil is modelled by a conglomerate of a hemisphere and a cylinder (

Figure 5). Local soil heterogeneity is modelled by a cylinder in the upper soil layer (

Figure 5b and

Figure 6).

Soil and Wenner array modelling using FEM-based software is a well-defined, simple, and fast process. For illustration, on the example of using Ansys software, several important steps of that process have been selected and described in detail as follows. The modelling process begins by drawing the geometries of the soil (represented by a hemisphere and a cylinder (

Figure 7a)) and the Wenner array (more precisely, current electrodes represented by smaller hemispheres (

Figure 7a)). After finishing drawing geometric objects, the electrical properties of the materials are assigned to specific geometric objects. The next step is choosing the type of excitation. In this paper, the current excitation is selected. For simplicity of modelling, the current of one ampere was injected into the upper base of the left smaller hemisphere, which represents the current electrode C1 (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7a). This was achieved by choosing a current excitation called “current source”. The upper base of the right smaller hemisphere, which represents the current electrode C2, is associated with current excitation called “current sink” (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7a). In this way, all injected current in the electrode C1 is extracted through the upper base of the right smaller hemisphere, by which the electrode C2 is modelled. After the above, the division of the computational domain into a finite number of elements follows (

Figure 7b). In terms of achieving the optimum between the accuracy and the duration of the numerical calculation, the division of the computational domain was performed by limiting the number of elements to 10,000 elements. Given that in reality the soil is of infinite dimensions (half-space), and it is represented (i.e., it is modelled) with a computational domain of finite dimensions (hemisphere plus cylinder) whose dimensions are

(

Figure 5a), there will be a certain inherent error in the numerical calculation [

14].

In order to reduce this type of error within acceptable limits, it is necessary that the dimension of the computational domain be at least ten times greater than the distance between the current electrodes C1 and C2 (

) [

14]. In the next step, an adaptive solver setup with a maximum number of passes equal to 15 and a percentage error of 1% was set. Given that the excitation is by DC current, the DC conduction solver was chosen to solve the EM problem. In the DC conduction solver, the quantity that is solved numerically is the electric scalar potential [

14]. In the DC conduction solver, current density and electric field are determined from the scalar electric potential according to the expressions (4) and (5) [

13].

where

is the electric field strength and

is the scalar electric potential.

where

is current density,

is the electrical conductivity of the soil, and is related to electrical resistivity

of the soil by expression

.

The apparent resistivity is determined as follows: On the soil surface, along the line that passes through the current electrodes, between the points −0.5a and +0.5a (

Figure 6), a polyline is drawn (

Figure 7a). The calculated voltage along the polyline can be accessed by making a Field Report, and is determined by the following expression [

13]:

where the integration curve “

C” corresponds to the polyline.

Once the voltage is determined, it enables the determination of the apparent resistivity. Using the programme module “Calculator” within the Ansys program, the apparent resistivity was calculated based on expression (1). Multiple calculations were performed for different distances between adjacent electrodes. For this purpose, a = 0.5 m was chosen for the initial distance between adjacent electrodes, and the distance between adjacent electrodes was increased in steps of 0.25 m up to 35.5 m. In the Ansys Maxwell software package, the process of automating simulations for different amounts of the variable “a” is achieved using Parametric Analysis. To demonstrate the influence of local soil heterogeneity on the measurement results obtained by Wenner’s method, simulations were carried out in the Ansys Maxwell software package. For this purpose, a common two-layer soil model was chosen. Also, it was chosen that the upper layer of the soil has a higher resistivity than the lower layer of the soil (), and the thickness of the upper soil layer of 5 m was chosen. The two-layer soil model is extended by adding local heterogeneity in the shape of a cylinder whose radius (0.5 m) which corresponds approximately to concrete pipes (for wastewater) buried in the ground. The influence of local heterogeneity of the soil, which can be expected during practical measurements, was analyzed.

4. Results and Discussion

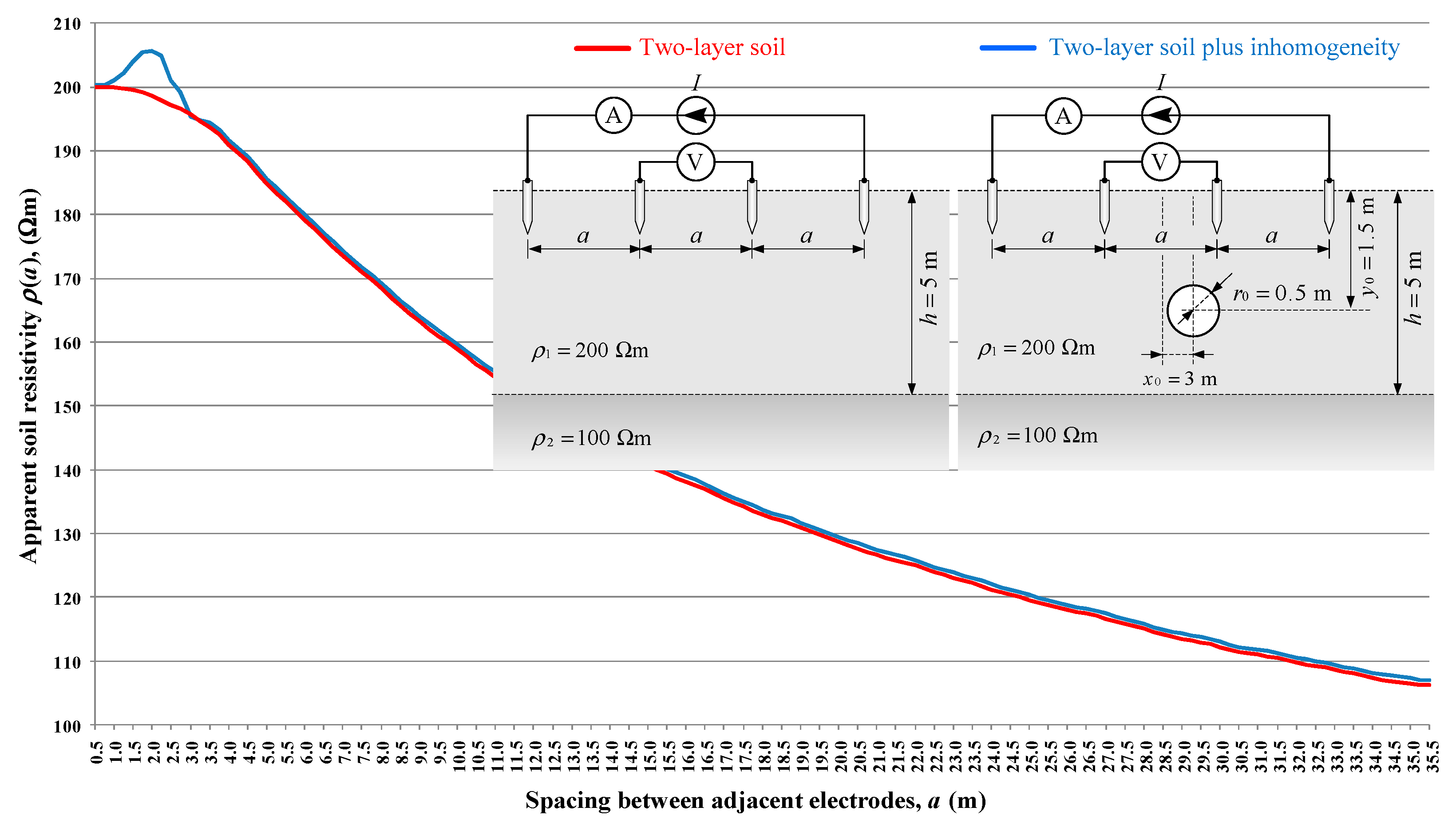

Using the previously described models, a FEM calculation for the determination of soil resistivity was performed. The results of FEM calculations are shown in

Figure 8 [

7]. By comparing the waveforms of apparent soil resistivity for cases with and without local soil heterogeneity, the influence of local heterogeneity is evident (

Figure 8 [

7]). Local soil heterogeneity positioned three metres horizontally from the centre of the Wenner array causes a local maximum (bulge) on the apparent soil resistivity curve (blue curve).

The local maximum on the curve for apparent soil resistivity corresponds to the space between adjacent electrodes a = 2 m. For a = 2 m, the position of the current electrode C2 is 3.5 m from the centre of the Wenner array, i.e., 0.5 m horizontally away from the centre of the local heterogeneity in the soil. The result is expected for the galvanic method; however, the Wenner method has a certain spatial sensitivity to changes in soil resistivity. For this reason, a certain offset is always present. Despite the aforementioned phenomenon, in practical applications, the method provides sufficiently accurate information about the area where the presence of pipes is suspected. The reason for which the presence of concrete pipes has manifested as an increase in apparent resistivity is that it acts as an electric insulator. The more extensive simulations in which the radius of the concrete pipes are varied would give a pattern that establishes the relationship between the height and width of the local maximum (bulge) on the apparent resistivity curve and the radius of the concrete pipes.

5. Conclusions

Despite the progress of other methods of measuring soil structure and soil composition, the galvanic method, also called the DC method, used for measuring soil structure and resistivity, is still widespread. The simplicity, numerous suppliers, and affordability of measuring equipment, as well as short training time for the operator, are some of the reasons for the galvanic method’s popularity. A more demanding part of the application of the galvanic method for measuring the resistivity of soil is the correct interpretation of the measured data. Local soil heterogeneities, whether natural or artificial, such as pipes and channels, can significantly complicate the interpretation of measurement data. This paper demonstrated that for such cases, operators in charge of data processing can be trained by analyzing the results of simulations obtained with the FEM-based software. With FEM-based software packages, it is possible to model and analyze different scenarios of local soil heterogeneities. One such case of local soil heterogeneity is presented in this paper.