1. Introduction

The efficient distribution of requests across multiple servers is a paramount factor for system performance, reliability, and scalability in modern distributed systems. Since the demand for cloud-based services, web applications, and microservices increases, optimal utilization of resources with minimal latency has become significantly challenging. Load balancing is the fundamental method to tackle these challenges, which is the process of distributing incoming traffic among a set of servers [

1]. Load balancing helps servers avoid overloading and improves overall performance.

Round Robin (RR), which is one of the conventional load balancing algorithms, introduces a simple algorithm by assigning requests to servers sequentially, ignoring their current workload or performance metrics [

2]. RR is effective in homogeneous environments; however, it may not perform that well in heterogeneous or dynamically changing server conditions. For example, while more capable servers remain underused, servers with lower processing capacity can become bottlenecks, resulting in increased latency and decreased throughput [

3].

Weighted Round Robin (WRR) differs from RR by assigning server-specific weights to servers to take into account differences in server capacities, distributing requests proportionally [

4]. Despite better performance in heterogeneous environments, WRR is limited by its static nature and cannot dynamically adapt to real-time fluctuations in server load or varying traffic patterns [

5]. Currently, there is an increasing demand for load balancing strategies that are both intelligent and adaptive, and capable of responding to dynamic system behavior.

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) give us possibilities for both predictive and adaptive load-balancing strategies. By analyzing historical traffic patterns and server performance metrics, ML models can theoretically predict the latency of a request if directed to each server, determine the one with the lowest latency, and direct the request to it, improving performance and reducing latency.

In this paper, we implement and evaluate a machine learning-based predictive load balancing approach alongside RR and WRR. It was expected to perform best since our approach determines the lowest expected latency based on request and container parameters.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

A comparative evaluation of Round Robin, Weighted Round Robin, and our predictive ML-based load balancing approach under heterogeneous workloads.

An implementation and experimental setup that illustrates the practical challenges of applying machine learning in load balancing in containerized environments.

An analysis of results.

2. Literature Review

Load balancing is one of the key strategies in distributed and cloud computing systems, contributing to more optimized resource utilization and a better user experience [

6]. There are several studies on traditional load-balancing algorithms, such as round robin (RR) [

7] and weighted round robin (WRR) [

4]. X. Zhou [

3] showed that RR performs poorly in heterogeneous environments, although RR offers simplicity and low computational overhead. Also, WRR does not adapt to real-time load fluctuations, although it improves when considering static server capacities [

8]. These extensive comparative analyses illustrate that traditional static algorithms perform poorly under varying system loads, especially in microservices and hybrid cloud environments, due to limitations [

9,

10].

Nguyen and Nguyen [

9] highlighted challenges in terms of scalability and fault tolerance, pointing out that existing WRR variants are often insufficient to handle rapid workload changes in real-world microservice architectures. Shafiq et al. [

10] also observed a significant gap in adaptive efficiency metrics by categorizing various load-balancing strategies.

Recently, the integration of machine learning (ML) and deep learning into load-balancing algorithms has been explored as a potential way to overcome these limitations [

11]. There are some studies comparing ML-based approaches with existing load balancing techniques. For example, ML-based approaches that predict server load and make intelligent allocation decisions using historical and live runtime data have shown improvements in throughput and latency compared to traditional methods [

12,

13]. Furthermore, reinforcement learning has been used to create adaptive and self-tuning load balancers, which dynamically optimize performance metrics [

13]. In addition, to predict resource usage and distribute load in containerized and cloud-native environments, novel ML models such as graph neural networks (GNNs) have been applied [

14].

The research gap is that existing ML-based load balancing approaches either rely on complex models (as shown in approaches above) or require fine-grained telemetry that may not be practical in real-world deployments [

12]. That is, there are several challenges in implementing ML-based approaches despite the potential they offer. In practice, ML models may face issues such as prediction inaccuracies and outdated telemetry data. These limitations can outweigh the benefits of predictive scheduling, especially in systems with strict latency requirements or limited resources.

In light of this, our research performs an experimental evaluation of a predictive ML-based load-balancing strategy in a containerized environment and compares it with RR and WRR. The novelty of this paper is that we implemented a new and relatively simple ML-based approach and conducted an experiment to explore the effectiveness of the new technique and how these challenges affect overall performance.

3. Methodology

This section shows the experimental setup, workload generation, load balancing algorithms, machine learning model, training procedure, and evaluation methodology.

3.1. System Setup

The experimental environment was deployed on a local workstation using Docker containers with different computational resources.

Container 1: 4 CPU cores, 12 GB memory

Container 2: 3 CPU cores, 9 GB memory

Container 3: 2 CPU cores, 6 GB memory

Each container runs a Go-based application designed to handle synthetic workloads. Workloads are defined by one parameter:

3.2. Workload Generation and Data Collection

A request generator script was implemented to create workloads. Request attributes include:

HTTP method: randomly sampled from {GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, PATCH}.

URL: dynamically composed from multiple resource segments (e.g., /users/orders/payments).

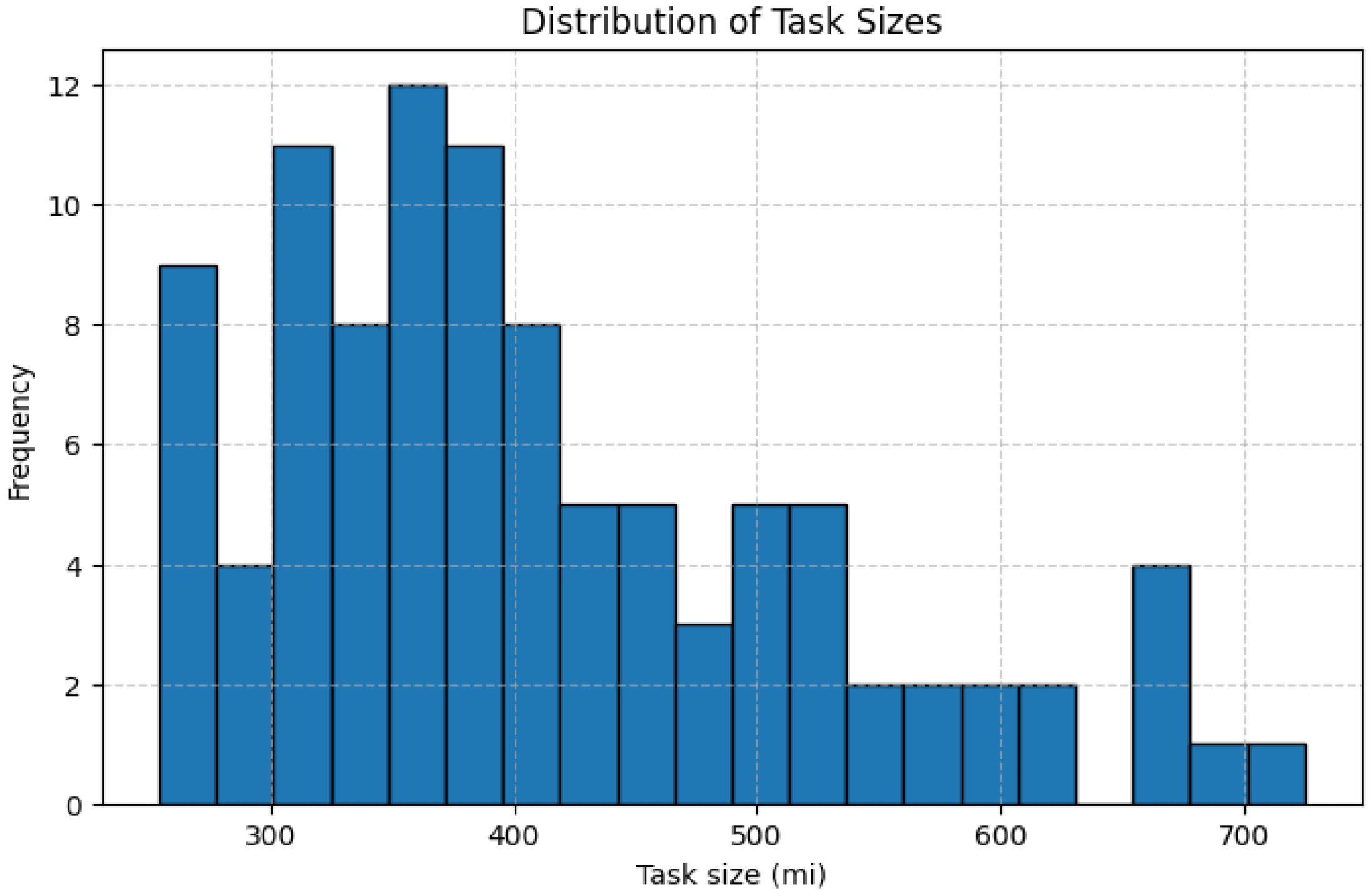

Task size (MI): sampled from a log-normal distribution (250–750 MI) to simulate varying computational demands (in

Figure 1).

Workload traffic was generated across a collection of 100 unique APIs, each designed to simulate different service endpoints in a real-world microservice environment. To ensure sufficient variability and robustness of the evaluation, every API was executed 200 times, resulting in a large number of independent request instances. Between successive requests, an artificial inter-arrival delay of 10 ms was introduced. This delay was carefully chosen: on one hand, it prevented the containers from being overwhelmed by a burst of simultaneous requests, while on the other hand it allowed the system’s monitoring component (exposed through the/stats endpoint) to respond in near real time. As a result, the workload reflected a controlled but realistic flow of traffic with both diversity and temporal separation.

For practical execution, a request generator was developed to automatically produce JSON-formatted input files. Each request definition captured essential attributes such as the HTTP method, target URL, and computational task size, thereby providing the simulator with sufficient information to mimic realistic service calls. These JSON inputs were then consumed by a request simulator, which issued the requests to the load balancer, recorded the corresponding responses, and persisted structured results including latency, status code, container assignment, and runtime metrics.

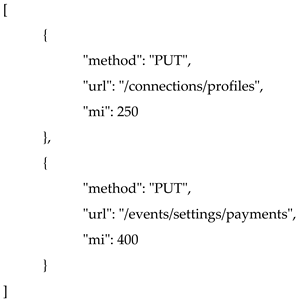

The snippet below illustrates two representative synthetic requests generated during the experiments:

The simulator sent these requests to the load balancer, recorded responses, and stored structured results (latency, status code, assigned container, and runtime metrics) in CSV format. 40,000 labeled samples were collected: 20,000 under Round Robin (RR) scheduling and 20,000 under Weighted Round Robin (WRR).

3.3. Load Balancing Algorithms

Three load-balancing strategies were implemented:

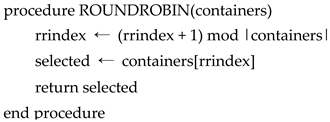

Round Robin (RR): assigns requests sequentially across containers.

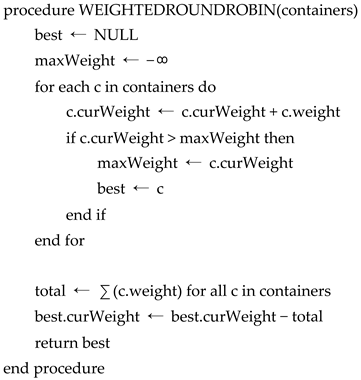

Weighted Round Robin (WRR): assigns requests proportionally to container weights.

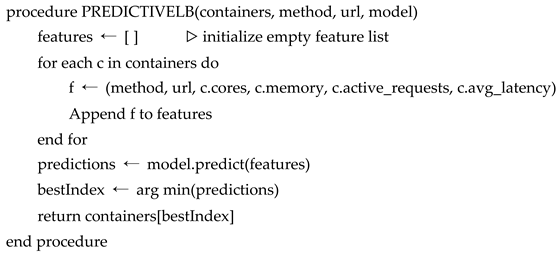

Predictive Load Balancing (PLB): employs a machine learning model to predict expected latency per container and chooses the one with the lowest predicted latency.

3.3.2. Weighted Round Robin

3.4. Machine Learning Model

The predictive load balancer uses CatBoost, a gradient boosting algorithm optimized for heterogeneous features. CatBoost was chosen based on Ileri’s study [

15], since it showed superior accuracy and stability over XGBoost, LightGBM, and Random Forest in similar predictive tasks.

3.5. Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

The target variable was the response latency (ms) of a request. Input features included:

Request attributes: HTTP method, URL.

Container resources: number of CPU cores, memory.

Runtime statistics: active requests, average latency of last 50 requests.

Training was conducted on 20,000 labeled requests (collected under Round Robin to ensure each container receives an equal share of requests for more consistent learning). Optuna was used for Bayesian hyperparameter tuning to minimize RMSE. The final parameters selected are shown in

Table 1.

On the validation data, the model achieved R

2 = 0.84; on test data, R

2 = 0.81. The prediction latency was on the order of microseconds, enabling real-time scheduling. The reason for selecting active requests and average latency instead of CPU and memory usages is that fetching CPU and memory statistics was significantly slower (a fetching interval of 500 ms using docker stats—stream, compared to 100 ms (for keeping frequency high while not overloading containers) + API latency using \texttt{/stats}; R

2 was 0.71 for validation and 0.60 for test data (hyperparameters are shown in

Table 2), due to the delayed statistics when using CPU and memory usage for prediction, which is noticeably lower than the former approach).

3.6. Experiment Process

Each of the three strategies (RR, WRR, PLB) was evaluated. For each, the request simulator executed the same workload distribution with 200 repetitions to ensure robustness. The responses were recorded and the /stats API was queried every 100 ms to capture the state of the container throughout the experiments.

3.7. Evaluation Metrics

From the list of load-balancing efficiency parameters identified by Shafiq et al. [

10], throughput and average latency were selected as the primary metrics due to their calculation feasibility.

These metrics allow for a fair comparison of both the efficiency and responsiveness of each strategy.

4. Results

We collected latency and throughput statistics from 20,000 requests executed under each approach to evaluate the effectiveness of the three load-balancing strategies. The same API requests were sent 200 times across all strategies.

The average latency and throughput for each strategy were calculated as:

where:

N = total number of requests,

latencyi = execution time of the i-th request,

task_size_MIi = size of the i-th task in million instructions.

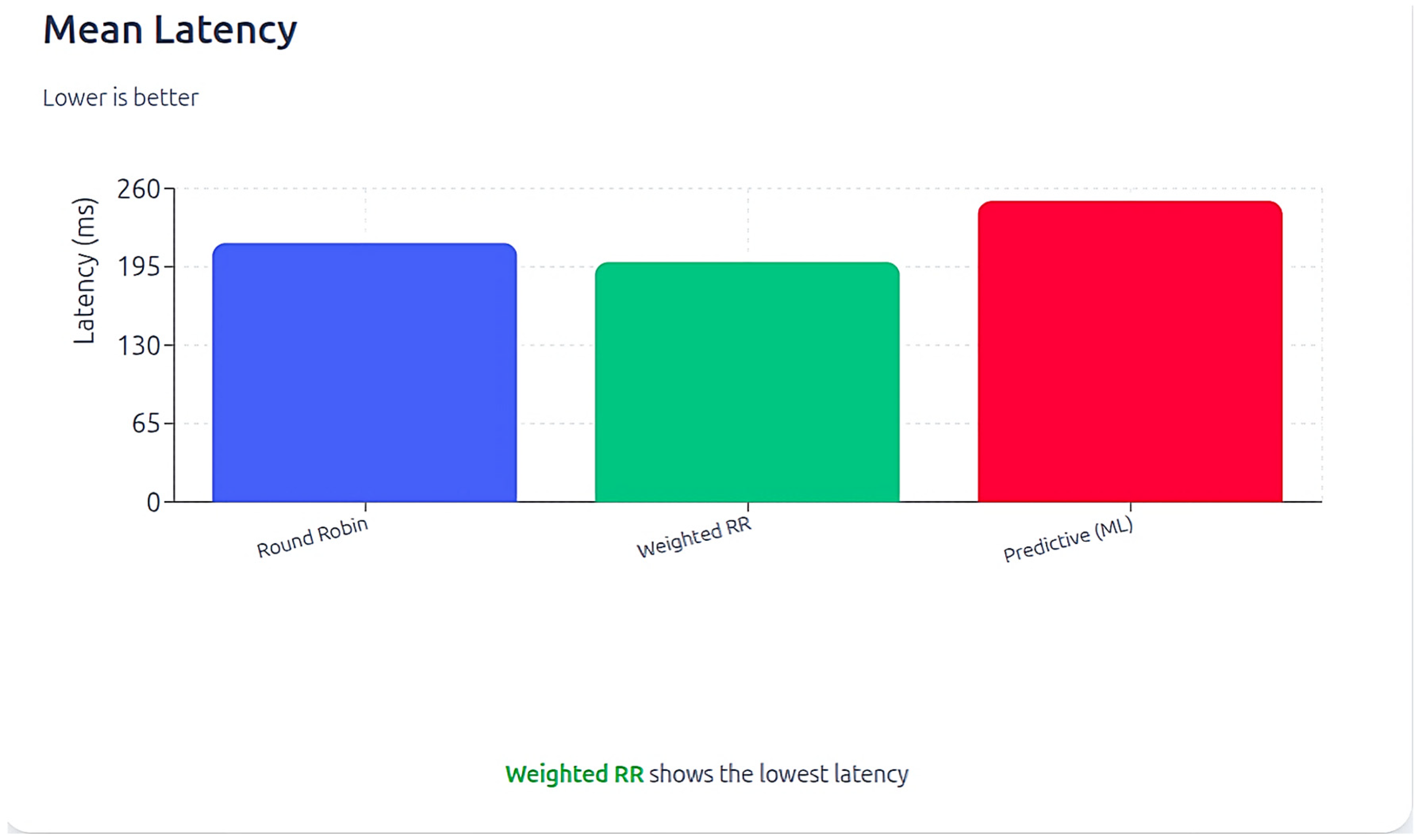

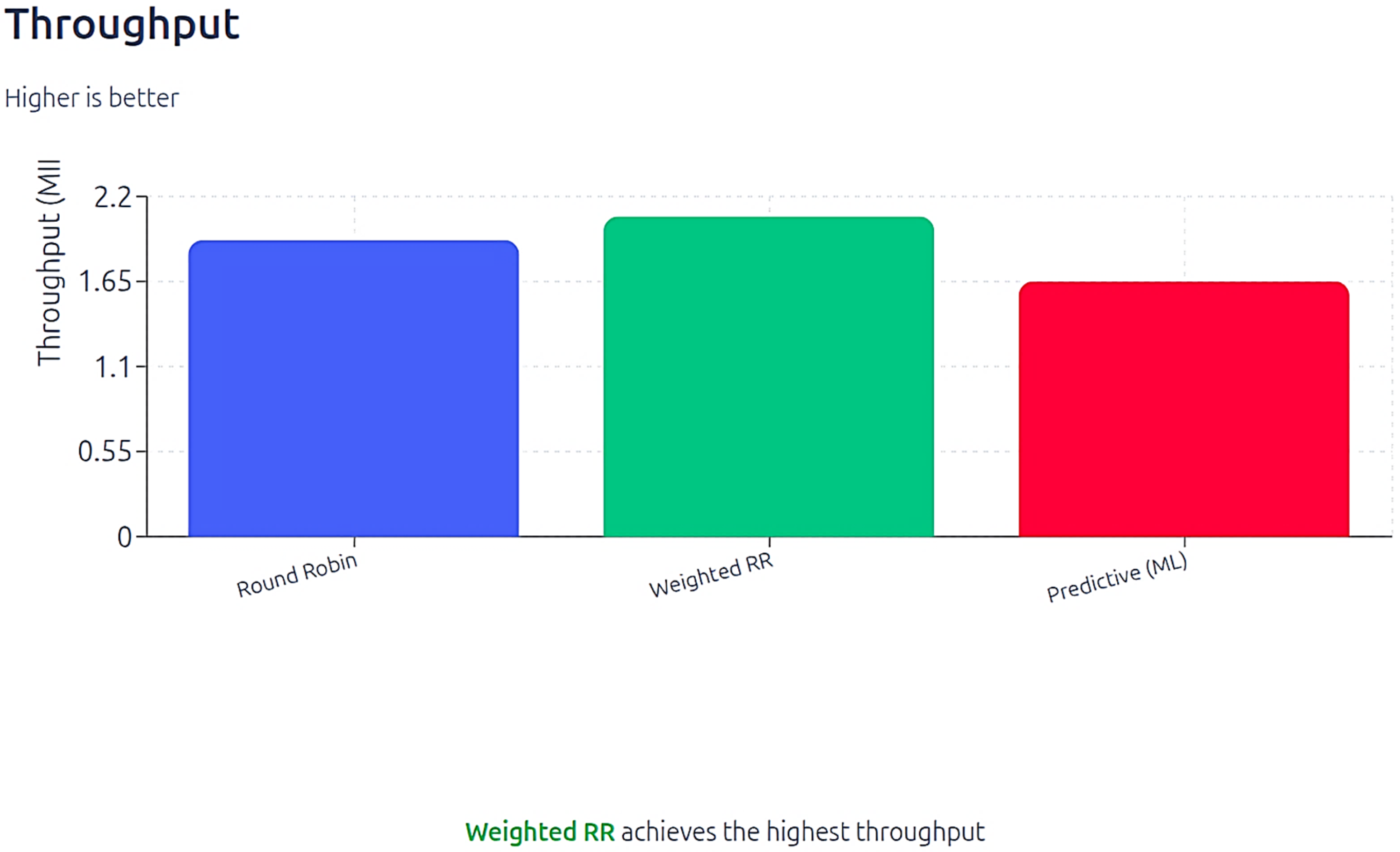

The visualizations below present the summarized results. Weighted Round Robin achieved the best overall performance, with the lowest mean latency (198.90 ms) and the highest throughput (2.07 MIPS) (see

Table 3,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Round Robin followed closely, with slightly higher latency (214.67 ms) and slightly lower throughput (1.92 MIPS). The predictive machine learning strategy, however, performed the worst, with the highest mean latency (249.63 ms) and the lowest throughput (1.65 MIPS).

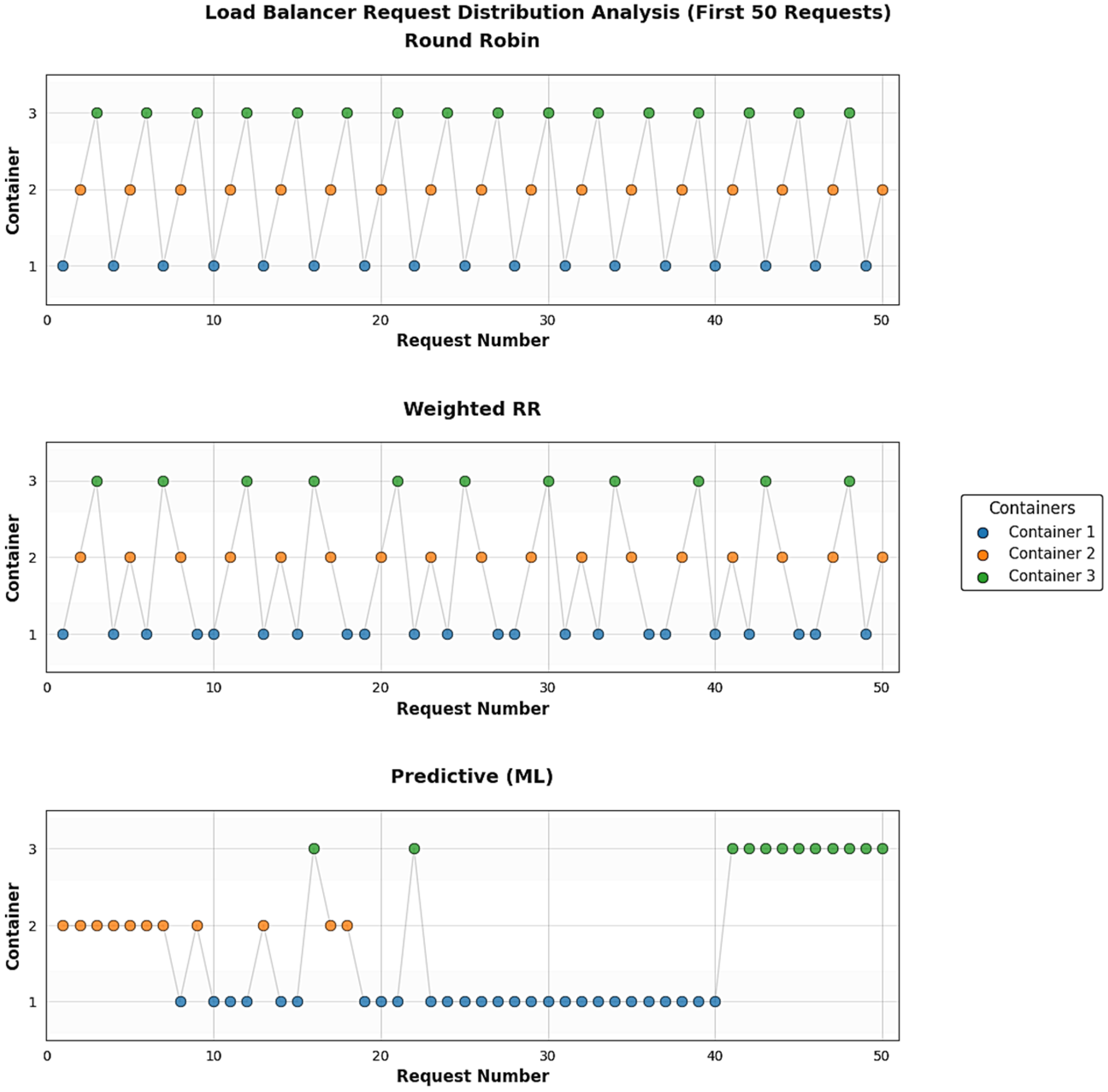

There are several deviations from the expected selection of containers, since requests can influence the decisions; however, almost the same containers are chosen consistently over time.

The study provides valuable information on the challenges of integrating ML into load balancing and highlights the vital role of real-time server feedback.

5. Conclusions

This paper exhibits a comparative study of two traditional load-balancing algorithms, namely Round Robin and Weighted Round Robin, and a new ML-based predictive load balancing strategy. Although there were positive expectations, the predictive approach performed worse, leading to high latency and low throughput compared to the others. Weighted Round Robin got the best overall results, followed by Round Robin.

The poor performance of the predictive model can be explained by its reliance on periodically fetched container statistics. The ML model continued to route requests to the last determined ‘best’ container between update intervals. Due to that, all requests were sent to a single container, causing the container to be overloaded and causing lower performance. This issue negatively affected the overall performance, illustrating that prediction alone is not enough without more frequent updates to the container metrics.

Figure 4 illustrates how containers were selected by load balancing strategies.

Although this paper showed that the machine learning-based predictive strategy underperformed relative to Round Robin and Weighted Round Robin, several directions for future research could address the observed limitations.

First, up-to-date server statistics are paramount; as the predictive model relies on periodically updated metrics, more frequent or real-time monitoring could prevent overloading a single server and improve decision accuracy.

Second, to adapt continuously without waiting for full statistics refresh cycles, incremental or online updates can be implemented in the predictive model. For example, server statistics can be calculated manually or by leveraging ML approaches based on requests sent and the latest server metrics until the next update. This would decrease the demand for faster fetching of server metrics and reduce the probability of sending all requests to the same server during update intervals.

By addressing these areas, the efficiency of ML-based predictive load balancing algorithms can be further improved, making them more effective in terms of optimized resource utilization and overall performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R. and T.A.; methodology, E.R.; software, E.R. and T.A.; validation, E.R. and T.A.; formal analysis, E.R.; investigation, E.R. and T.A.; resources, E.R.; data curation, E.R. and T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are presented in the article. For any clarifications, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cardellini, V.; Yu, P.S.; Colajanni, M. Dynamic Load Balancing on Web-Server Systems. IEEE Internet Comput. 1999, 3, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balharith, T.; Alhaidari, F. Round Robin Scheduling Algorithm in CPU and Cloud Computing: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Computing Applications and Information Security (ICCAIS), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1–3 May 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Rathgeb, E.; Dreibholz, T. Improving the Load Balancing Performance of Reliable Server Pooling in Heterogeneous Capacity Environments. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of Sustainable Internet—Third Asian Internet Engineering Conference (AINTEC 2007), Phuket, Thailand, 27–29 November 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Casale, G. Evaluating Weighted Round Robin Load Balancing for Cloud Web Services. In Proceedings of the 2014 16th International Symposium on Symbolic and Numeric Algorithms for Scientific Computing (SYNASC), Timisoara, Romania, 22–25 September 2014; pp. 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, D.C.; Uthariaraj, V.R. Load Balancing in Cloud Computing Environment Using Improved Weighted Round Robin Algorithm for Nonpreemptive Dependent Tasks. Sci. World 2016, 2016, 896065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahakar, M.; Mahajan, S.A.; Patil, L. A Survey on Various Load Balancing Approaches in Distributed and Parallel Computing Environment. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2023, 11, 187–196. Available online: https://ijisae.org/index.php/IJISAE/article/view/3511 (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Anusha, S.K.; Bindu Madhuri, N.R.; Nagamani, N.P. Load Balancing in Cloud Computing Using Round Robin Algorithm. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2014, 2, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, G.; Sinha, D.K. Enhanced Weighted Round Robin Algorithm to Balance the Load for Effective Utilization of Resource in Cloud Environment. EAI Endorsed Trans. Cloud Syst. 2020, 6, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesbahi, M.; Rahmani, A.M. Load Balancing in Cloud Computing: A State of the Art Survey. IJMECS 2016, 8, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Kavitha, G. Load Balancing in Cloud Computing—A Hierarchical Taxonomical Classification. J. Cloud Comput. 2019, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, A.A.A.; Alsabbagh, A.; Maraqa, R.; Alzubi, S. Load Balancing Techniques in Cloud Computing: Extensive Review. ASTESJ 2021, 6, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, K. Reinforcement Learning-Based Adaptive Load Balancing for Dynamic Cloud Environments. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.04896. [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaik, P.; Khan, M.Z.; Mansuri, M. Large Language Models and Reinforcement Learning for Efficient Load Balancing in Dynamic Cloud Environments. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 6553–6565. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.R. Dynamic Load Balancing in Cloud Computing: Optimized RL-Based Clustering with Multi-Objective Optimized Task Scheduling. Processes 2024, 12, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileri, K. Comparative Analysis of CatBoost, LightGBM, XGBoost, RF, and DT Methods Optimized with PSO to Estimate the Number of k-Barriers for Intrusion Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2025, 16, 6937–6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |