A Low-Cost 3D Printed Piezoresistive Airflow Sensor for Biomedical and Industrial Applications †

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The design of a low-cost and customizable airflow sensor fabricated solely through 3D printing,

- Experimental validation of its performance in biomedical and industrial contexts, and

- Demonstration of its suitability for disposable and resource-constrained applications, including direct resistance readout without external signal conditioning.

2. Related Work

3. Design of the Airflow Sensor

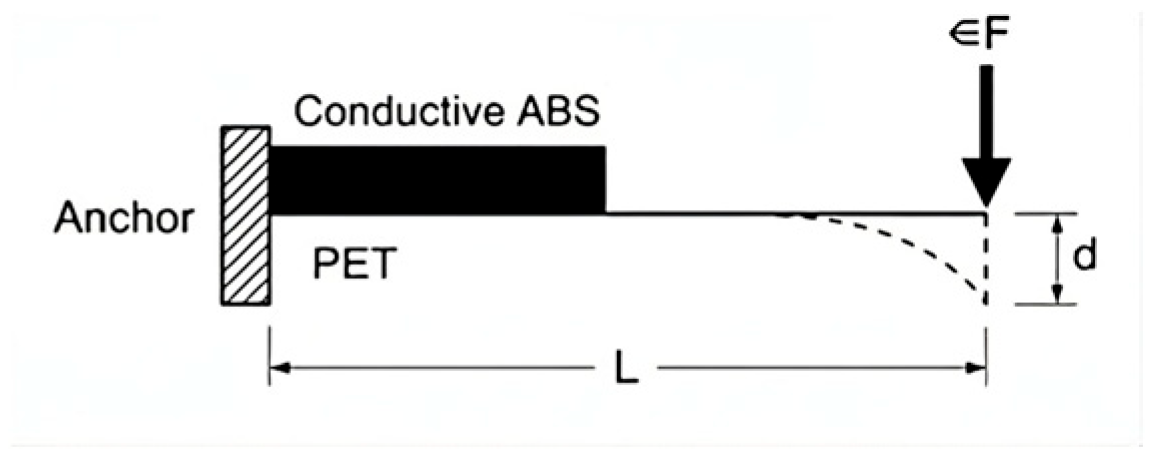

3.1. Mechanical Design Based on Cantilever Beam Model

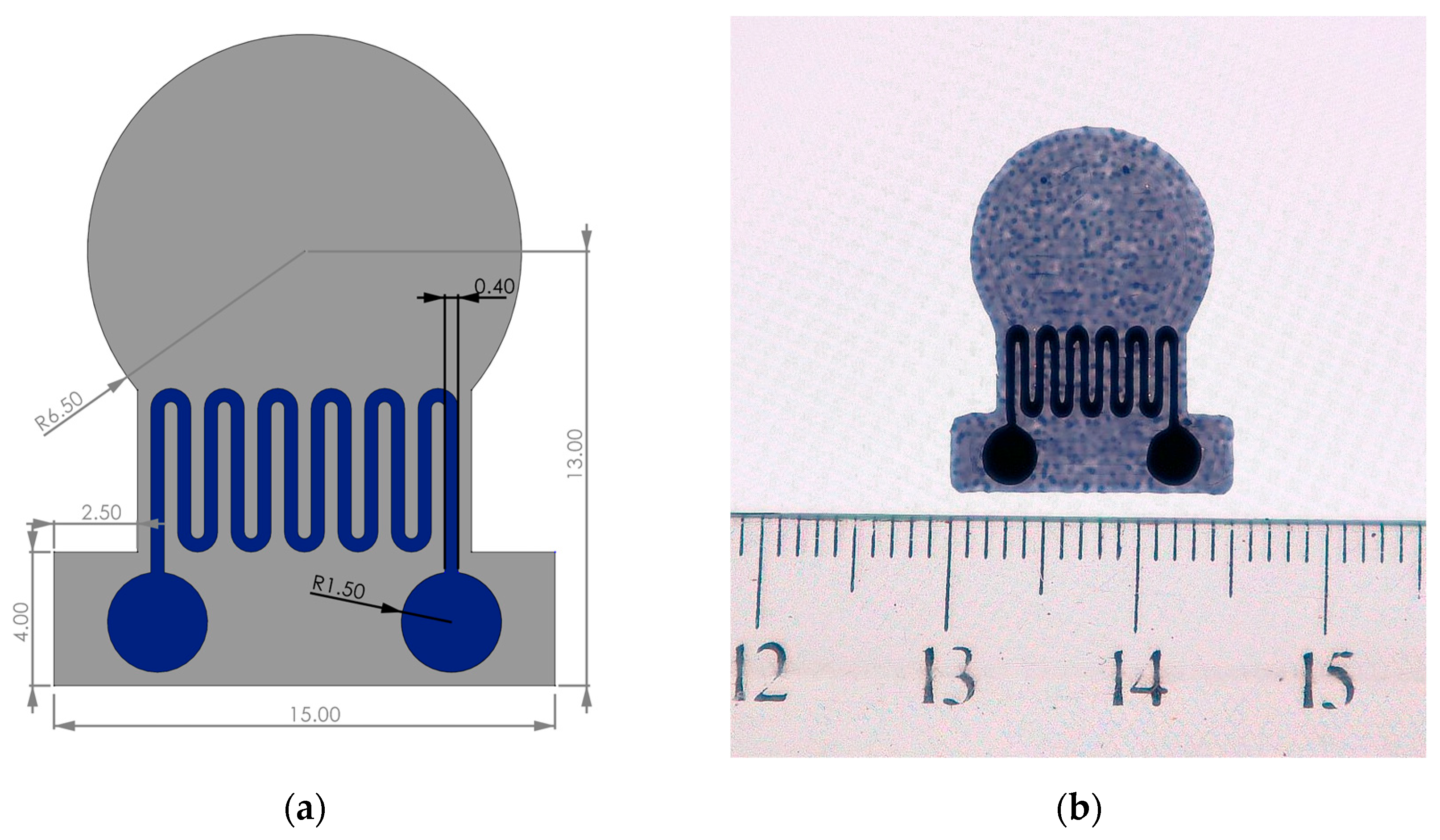

3.2. Practical Sensor Design and Structural Choices

3.3. Measurement and Readout Approach

4. Experimental Results

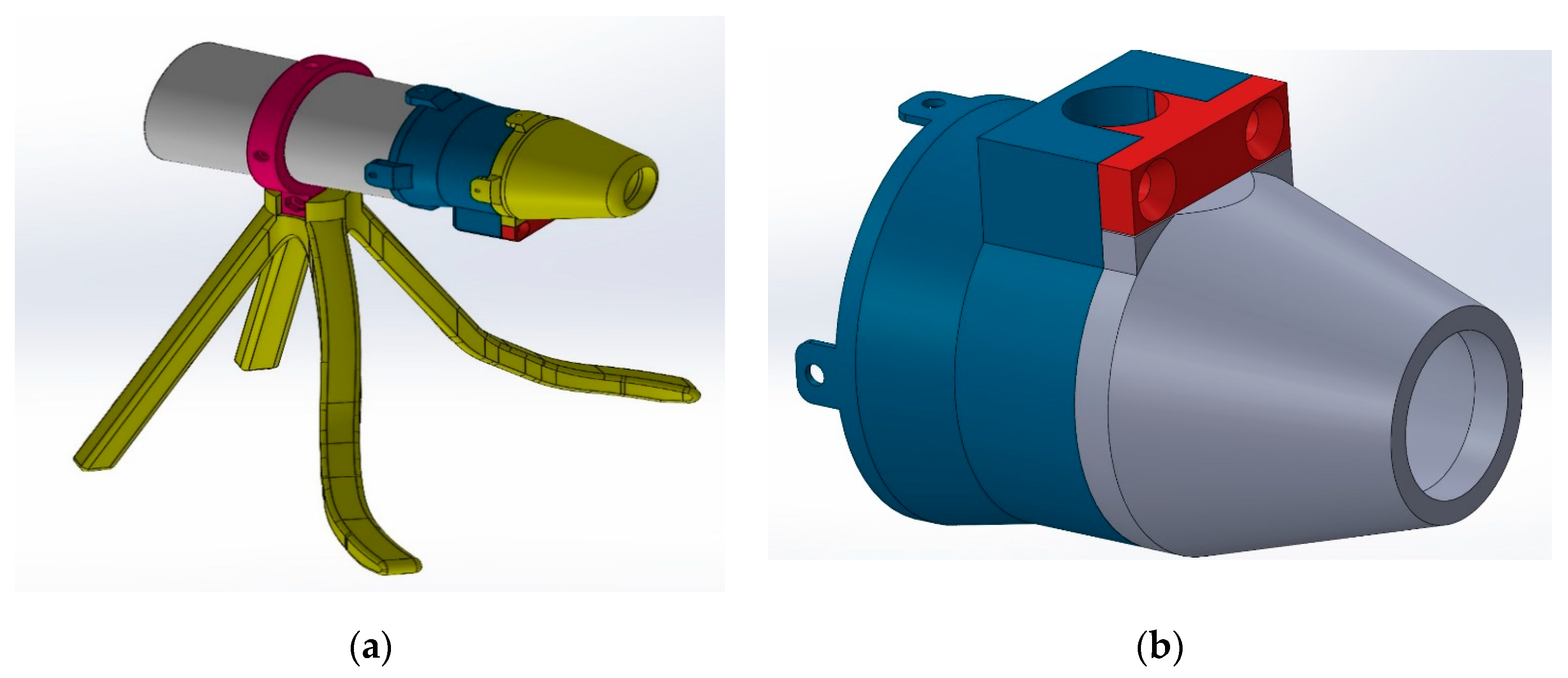

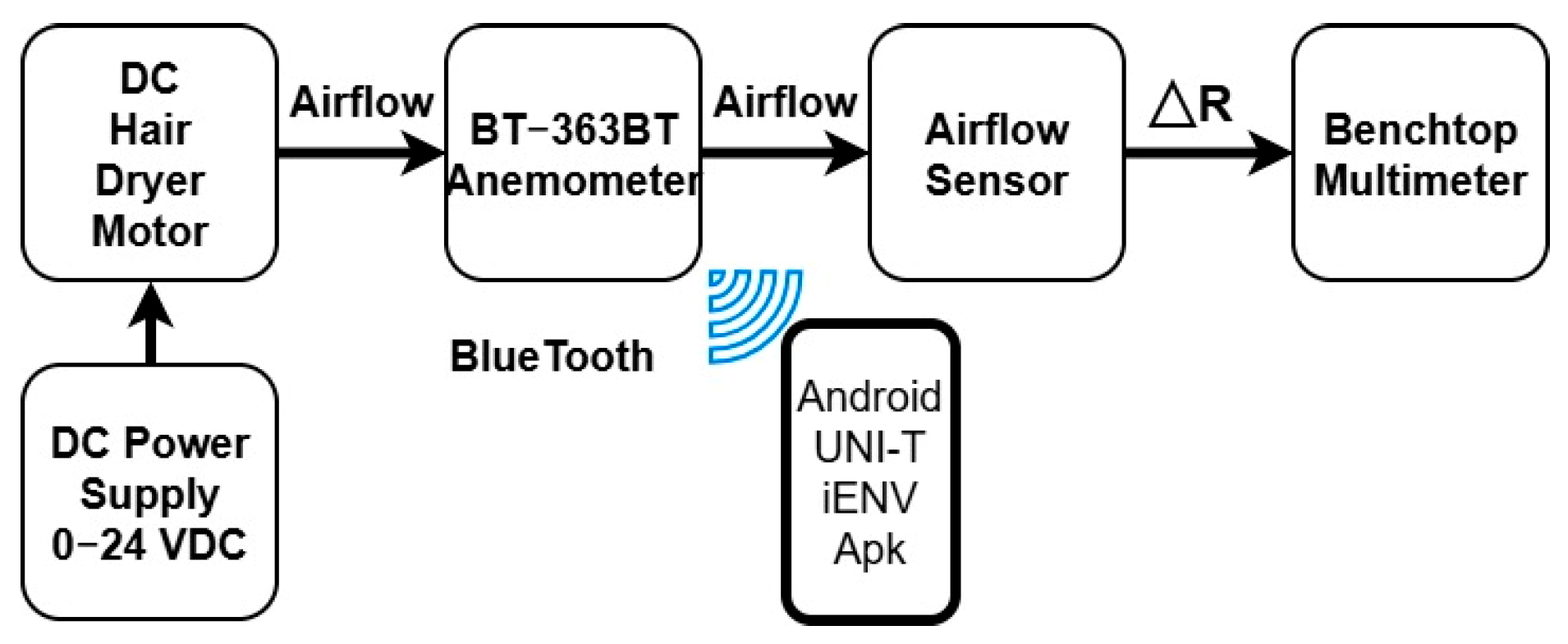

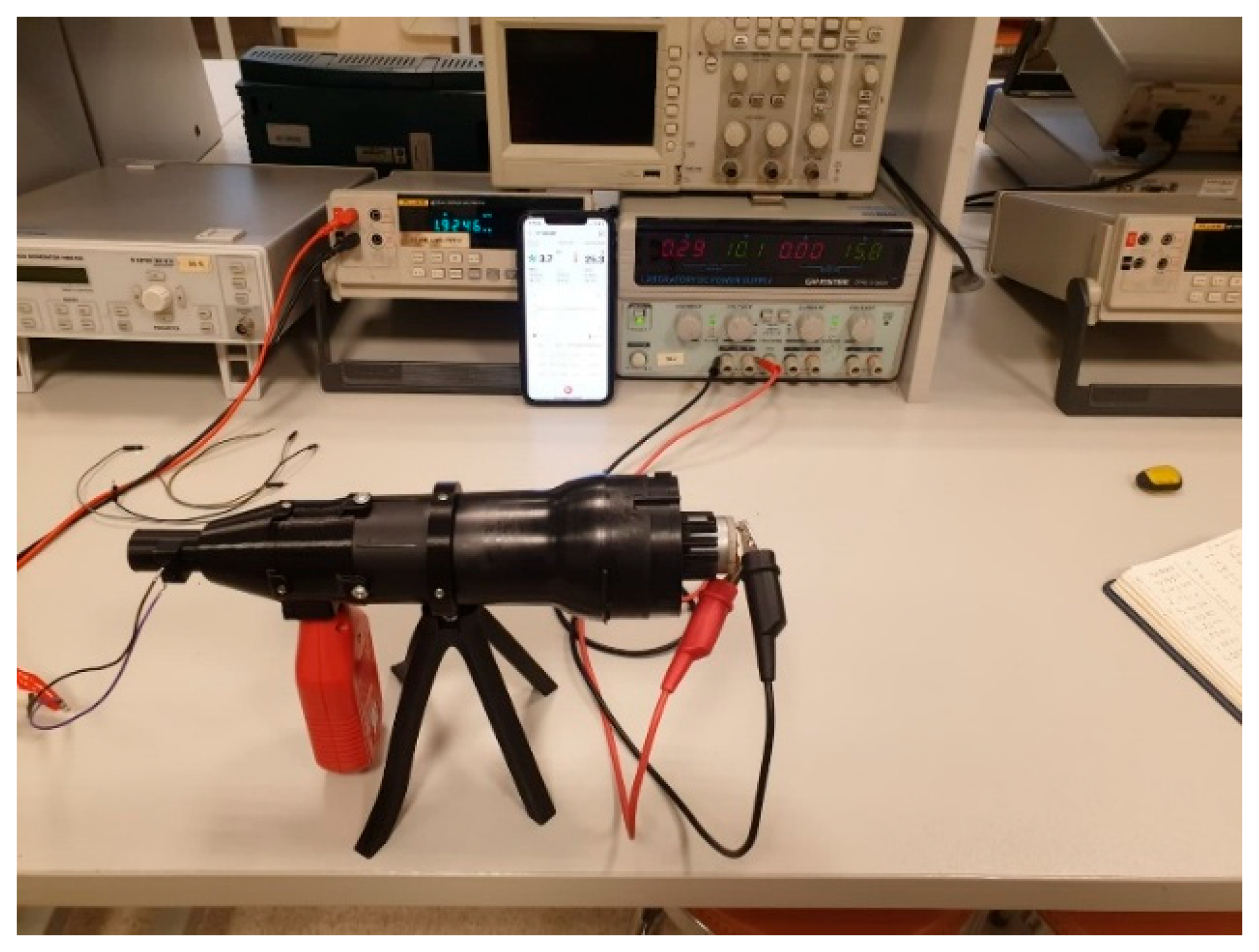

4.1. Experimental Setup

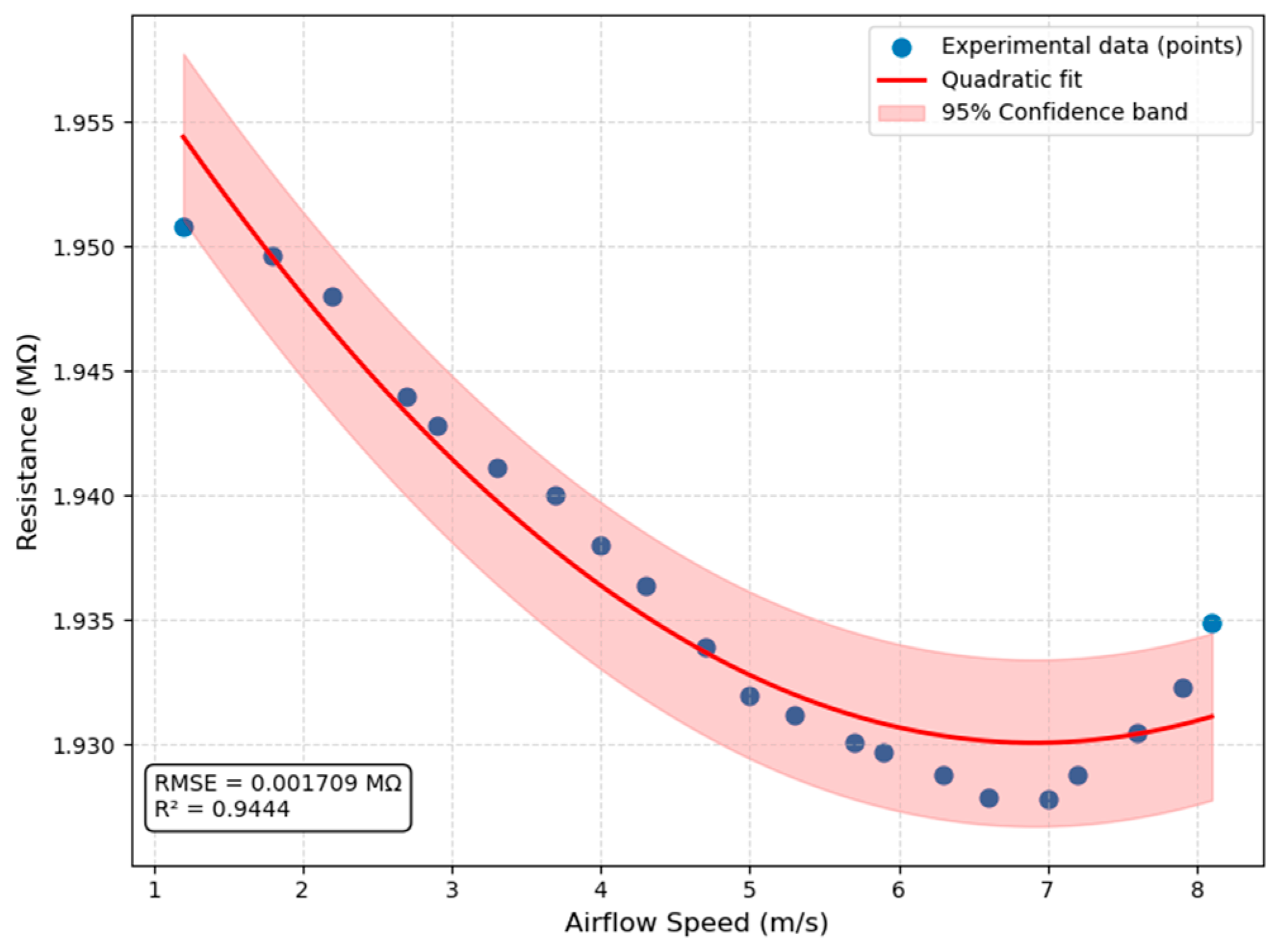

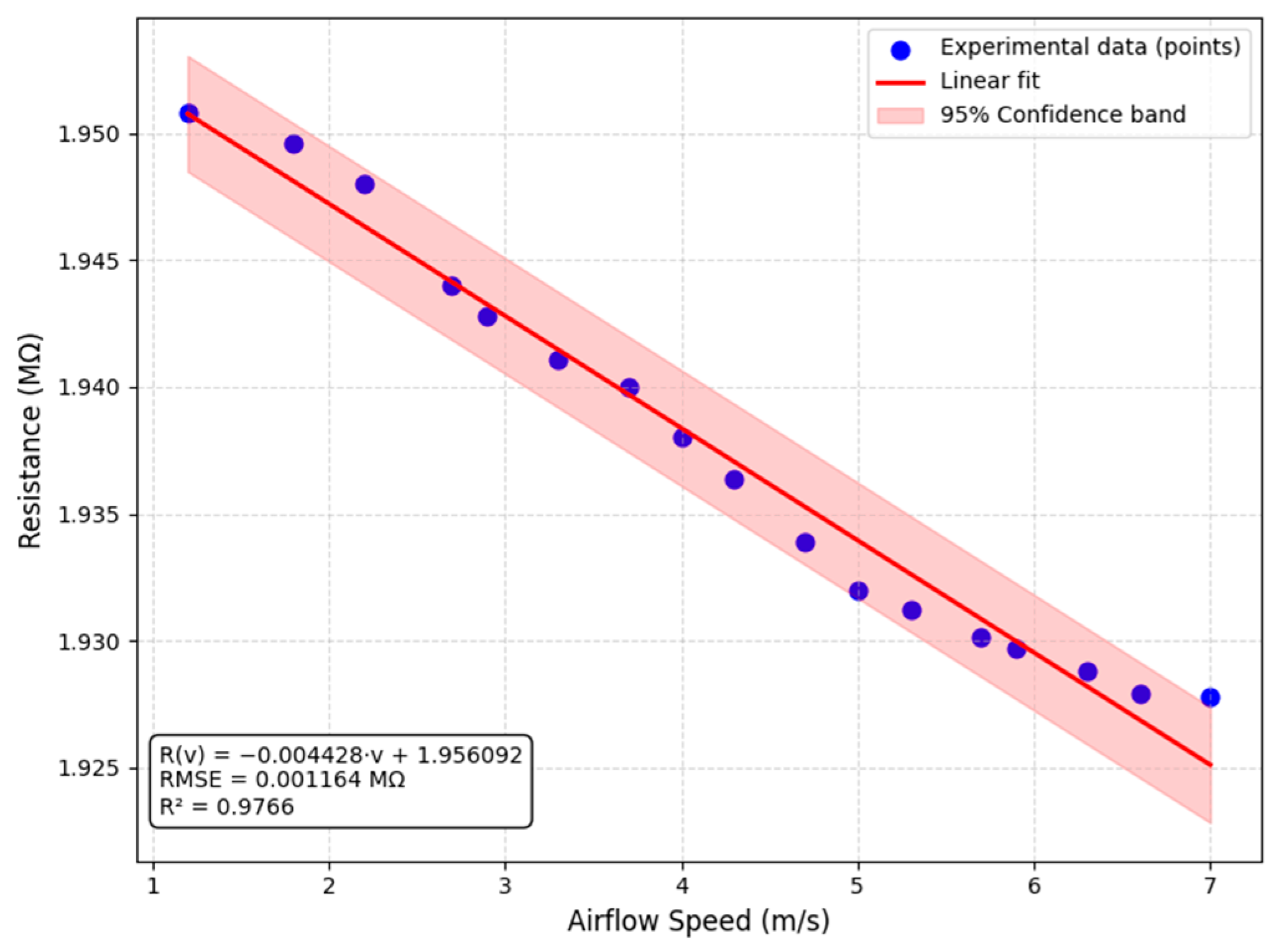

4.2. Sensor Characterization

4.3. Extracted Characteristics

- Minimum detectable speed vmin: 1.2 m/s, corresponding to ΔR ≈ 400 Ω.

- Maximum tested speed vmax: 7.0 m/s, with ΔR ≈ 16 kΩ.

- Resolution: 9.27 Pa equivalent, enabled by the large-scale resistance changes measured directly on a DMM.

- Dynamic Range: up to ~51.5 kΩ across the tested range.

4.4. Comparative Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malik, S.; Ahmad, M.; Punjiya, M.; Sadeqi, A.; Baghini, M.S.; Sonkusale, S. Respiration Monitoring Using a Flexible Paper-Based Capacitive Sensor. In Proceedings of the IEEE Sensors, New Delhi, India, 28–31 October 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Mwangi, M.; Li, X.; O’Brien, M.; Whitesides, G.M. Based Piezoresistive MEMS Sensors. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, O.; Azami, M.; Ameli, A.; Salman, E.; Stanacevic, M.; Willing, R.; Towfighian, S. Experimental Investigation of 3D-Printed TPU Triboelectric Composites for Biomechanical Energy Conversion in Knee Implants. Sensors 2025, 25, 6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, L.T.; Bottin-Noonan, J.; Armitage, L.; Alici, G.; Sreenivasa, M. 3D-Printed Insole for Measuring Ground Reaction Force and Center of Pressure During Walking. Sensors 2025, 25, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mubasshira, N.; Rahman, M.; Uddin, N.; Rhaman, M.; Roy, S.; Sarker, S. Next-Generation Smart Carbon–Polymer Nanocomposites: Advances in Sensing and Actuation Technologies. Processes 2025, 13, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.-L.; Tian, H.; Xie, D.; Yang, Y. Flexible Graphite-on-Paper Piezoresistive Sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 6685–6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.; Peng, B.; Liang, G.; Yu, S. Recent Advances in Porous Polymer-Based Flexible Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. Polymers 2025, 17, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Y.; Huang, S.; Huang, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, M.; Gao, L. Dual-Mode Flexible Pressure Sensor Based on Ionic Electronic and Piezoelectric Coupling Mechanism Enables Dynamic and Static Full-Domain Stress Response. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, T.; Phan, H.-P.; Dao, D.V.; Woodfield, P.; Qamar, A.; Nguyen, N.-T. Graphite on Paper as Material for Sensitive Thermoresistive Sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 8776–8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.Y.; Goh, C.-H.; Yap, K.Z.; Ramakrishnan, N. One-Step Fabrication of Paper-Based Inkjet-Printed Graphene for Breath Monitor Sensors. Biosensors 2023, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Arifuzzman, A.K.M.; Hossain, K.; Gardner, S.; Eliza, S.A.; Alexander, J.I.D.; Massoud, Y.; Haider, M.R. A Low-Power Sensitive Integrated Sensor System for Thermal Flow Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2019, 27, 2949–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.C.; Budynas, R.G.; Sadegh, A.M. Roark’s Formulas for Stress and Strain, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Tran, V.-T.; Du, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, C. A Direct-Writing Approach for Fabrication of CNT/Paper-Based Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors for Airflow Sensing. Micromachines 2021, 12, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3DYazdiralim.com. Frosch Conductive ABS Filament Specifications. Available online: https://www.3dyazdiralim.com/frosch-iletken-abs-filament (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Anuar, A.F.M.; Johari, S.; Wahab, Y.; Zainol, M.; Fazmir, H.; Mazalan, M.; Arshad, M. Development of a Read-Out Circuitry for Piezoresistive Microcantilever Electrical Properties Measurement. In Proceedings of the IEEE Regional Symposium on Micro and Nanoelectronics (RSM), Penang, Malaysia, 19–21 August 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| Material | Type/Form | Key Properties (Typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Conductive PET Filament (1.75 mm) | Substrate/Base film | Thickness: ~250 µm (adjustable) Density: ~1.38 g/cm3 Tensile Strength: 55–75 MPa Electrical Resistivity: >1015 Ω·cm (insulator) |

| Conductive ABS Filament (1.75 mm) | Piezoresistive/Sensing Element | Resistivity: ~0.6–1.0 Ω·cm (depends on grade) |

| Specification | Our Work | Ref. [14] | Ref. [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensing material | Conductive ABS | Carbon nanotubes | Graphite pencil |

| Substrate material | PETg | polyimide | A4 paper |

| Fabrication technique | FDM 3D printed | Direct-writing | Hand-drawing |

| Fabrication duration | 1 min | >8 h | <30 min |

| Sensitivity | 967 Ω/Pa | 1.00537 kPa−1 | 0.9 Mv/mV |

| Resolution | 9.27 Pa | NA | 500 μN |

| Detection Limit | 83.27 Pa | 153 Pa | NA |

| Operation Range | 0.88–26.68 Pa | 0–3 kPa | 0–50 mN |

| Bill of Material | <$0.05 | NA | <$0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tek, U.; Nişancı, M.A.; Çiçek, İ. A Low-Cost 3D Printed Piezoresistive Airflow Sensor for Biomedical and Industrial Applications. Eng. Proc. 2026, 122, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122016

Tek U, Nişancı MA, Çiçek İ. A Low-Cost 3D Printed Piezoresistive Airflow Sensor for Biomedical and Industrial Applications. Engineering Proceedings. 2026; 122(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122016

Chicago/Turabian StyleTek, Utkucan, Mehmet Akif Nişancı, and İhsan Çiçek. 2026. "A Low-Cost 3D Printed Piezoresistive Airflow Sensor for Biomedical and Industrial Applications" Engineering Proceedings 122, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122016

APA StyleTek, U., Nişancı, M. A., & Çiçek, İ. (2026). A Low-Cost 3D Printed Piezoresistive Airflow Sensor for Biomedical and Industrial Applications. Engineering Proceedings, 122(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026122016