1. Introduction

The automotive industry is one of the biggest pollutant emission generators that uses internal combustion engine–based powertrains to convert a fuel’s chemical energy into mechanical energy [

1]. Ammonia has been successfully used in the past as an internal combustion engine fuel; its feasibility was proven during World War II, when conventional fossil fuels were in short supply. Belgium used it as a means to power its bus fleet. In the 1960s the US army carried out studies regarding the use of NH

3 as a substitute for classical hydrocarbon fuels in spark ignition and compression ignition engines [

2].

Ammonia is an effective hydrogen carrier, having 1.5 mols of hydrogen per mol of ammonia, equivalent to 107 kg of hydrogen per liquid ammonia cubic meter. Its freezing point is low (−77.73 °C), making it an adequate fuel for extreme cold conditions [

3]. Ammonia is lighter than air, with a density of 0.718 kg/m

3, and is highly soluble in water, which ensures leak control in order to avoid the risk of fire and explosion. Ammonia does not attack carbon steels easily but has a high reactivity with copper and copper alloys, therefore fittings and other equipment in direct contact with ammonia should not contain copper or its alloys.

The lower viscosity of ammonia helps with fuel atomization and droplet formation during injection. Storing ammonia is similar to LPG, its vapor pressure being around the same interval. With a high value octane number (>130), ammonia is suited as a fuel for high-compression engines because of its knock-preventing properties.

Some of the disadvantages of ammonia regarding its application in internal combustion engines are its low calorific value, low boiling point, lower laminar burning speed, high autoignition temperature, relatively high minimum ignition energy, low adiabatic flame temperature, long autoignition delay time, low radiation intensity, high latent heat of vaporization, and narrow flammability limits. These characteristics make it relatively difficult to use ammonia as a single fuel in internal combustion engines. However, ammonia can be used in a mixture with diesel or any other fuel with a lower autoignition temperature, in a dual-fuel diesel engine, which can lead to a significant reduction in carbon-based emissions. The operation of compression ignition engines in dual-fuel mode with ammonia in volumetric fractions of up to 95% has been reported in the literature. The combustion performance of the engine depends on the cetane number (CN) of the secondary fuel. A higher cetane number provides optimal performance, with short autoignition delay and high combustion efficiency [

4].

Under normal engine operating conditions, ammonia combustion produces nitrogen oxides (NO

x) at higher levels than those generated by other fuels. These pollutants contribute significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions and are also a major factor in the formation of acid rain [

5]. Rich air fuel mixture combustion conditions can mitigate NO

x formation, but this results in increased amounts of unreacted ammonia. The equivalence ratio should be maintained around 1.1 (excess air ratio λ = 0.9) to limit both NO

x emissions and the amount of unreacted ammonia [

1].

The use of ammonia as a marine fuel has significant potential to substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions and enable shipowners to gradually transition toward the use of renewable energy sources [

5]. A 2014 study conducted for the International Maritime Organization (IMO) [

6] on greenhouse gas emissions estimates that ammonia will become one of the main marine fuels in the future, with between 15% and 95% of ships expected to be fueled with ammonia. Currently, only 0.2% of ships use ammonia as a fuel.

Maritime regulations concerning emission limits are expected to become increasingly strict.

In the literature, there are some studies that have investigated the use of ammonia as a fuel, either in compression ignition (CI) engines or spark ignition (SI) engines [

5]. These studies have shown that, at a controlled load, an engine can operate in a stable and efficient manner when injection dosing for the main fuel is modified, turbochargers are used, and a constant air-to-ammonia ratio is maintained.

However, during transient operating conditions, such as acceleration, it has been observed that the engine suffers from increased ignition delay due to the intake pressure dropping below 5 bar. Consequently, Hollinger [

7] recommended the use of high compression ratios (>20:1), taking advantage of ammonia’s high-octane rating, and introducing gaseous ammonia into the intake airflow at a constant equivalence ratio in an effort to improve the combustion process.

Ammonia’s higher latent heat of vaporization limits its injection in the liquid phase, as a higher amount of energy is required for its vaporization. As a result, the reduction in cylinder temperature has a negative effect on autoignition, making it necessary to increase the compression ratio in order to achieve the high autoignition temperature required by the fuel. A conventional compression ignition engine can operate on ammonia with minimal modifications, primarily involving fuel storage and supply systems.

For compression ignition engines, Kong et al. [

8] studied the emissions and combustion properties of a compression ignition engine running on ammonia and dimethyl ether (DME) blends. In order to obtain ignition, ammonia was directly injected into the intake manifold, resulting in a premixed air–ammonia–DME mixture. In the experiment, a composition of 95% ammonia and 5% DME was used. With the addition of ammonia into the engine, torque increased substantially. Exhaust ammonia emissions were significantly lower with direct injection than with other ammonia supply methods, and the resulting power output increased as the ammonia dosing was increased.

Increasing the ammonia dose led to longer ignition delays at low engine loads due to ammonia’s longer ignition delay and lower flame speed. However, soot emissions remained low, and ammonia emissions in the exhaust were only a few hundred ppm under most of the engine testing conditions. NOx emissions increased due to the additional formation of nitrous oxides because of the nitrogen content in the ammonia molecule.

Cyclic variability in engine operation also increased. When higher concentrations of ammonia are used, engine modifications, such as increasing the injection pressure, are necessary to achieve better combustion at higher loads.

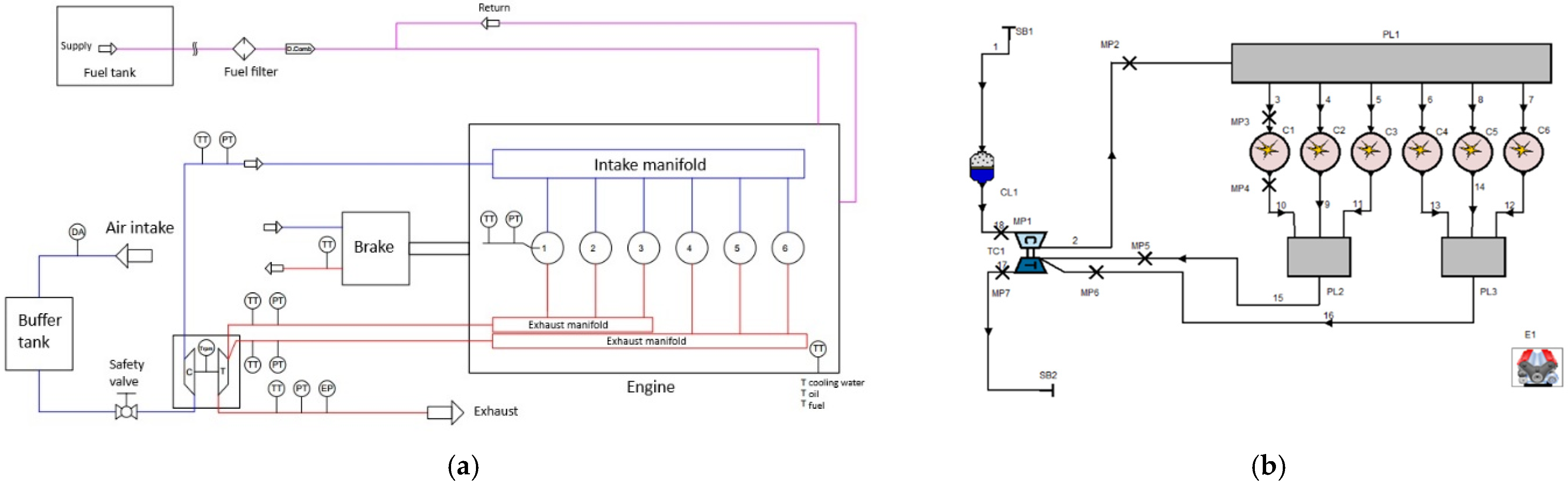

4. Simulation Results

The calibration engine model was first run using standard diesel fuel species, as defined in the software database. For engine dual-fuel operation, the main hypothesis is that the diesel–ammonia mixtures are simultaneously directly injected inside the cylinder by dual-fuel injectors, considering different ammonia mass fractions of 10%, 20%, and 30%. A study of pure diesel shows that engine power (P

e) and torque (M

e) increase with the amount of applied load. Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) decreases and the Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) increases with load because the engine operates closer to its optimal thermal efficiency and therefore produces power more effectively at higher loads. Under high load the fuel is better atomized; therefore, the efficiency increases (see

Figure 2).

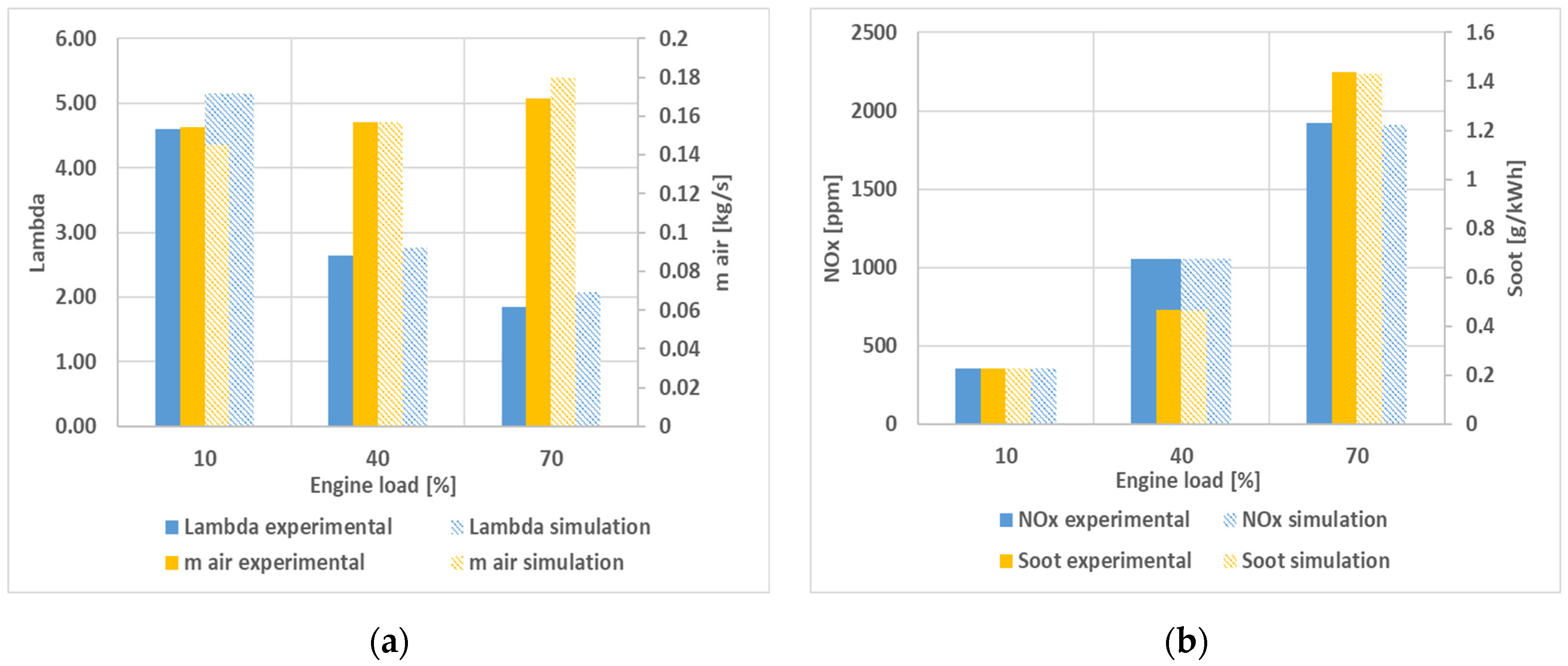

Air excess ratio (λ) and air mass flow (m

air) are directly correlated. Compression ignition (CI) engines run with reduced air excess when under higher loads because the fuel quantity required is higher. It can be observed that while lambda decreases with load, engine air consumption increases. The relative air–fuel ratio λ obtained by simulation is higher than the measured experimental values. Pollutant emissions are a direct consequence of the combustion process. In AVL BOOST simulation software, the AVL MCC combustion model was used with internal mixture preparation. This method predicts NO

x production based on the amount of fuel in the cylinder and the turbulent kinetic energy [

10]. Zuhair Aldarwish et al. highlight in their paper the influence of different loads and engine speeds on pollutant emissions. Higher combustion temperature and longer combustion duration lead to an increase in NO

x and soot. In

Figure 3, the relative air–fuel ratio, air mass flow rate, and pollutant emission variation by load are plotted.

Relative errors for the engine parameters under the test conditions studied are presented in

Figure 4. It can be observed that the errors for the mass airflow and air excess ratio are in the range of 5% to 12% at all engine loads, while for the other parameters, the errors are lower than 5%. Therefore, the model is considered validated against experimental data. At light load (10%), the simulation results for torque and power show relative errors of 14% with respect to the measured values, and hence the model validation was considered acceptable.

Fuel mixtures were studied for each tested condition using the following mass fractions of ammonia: 10%, 20%, and 30%. Due to the mixture’s lower calorific value, the effective power Pe decreased and BSFC increased. The pressure inside the cylinder during combustion is directly related to the power. It represents the force that pushes on the piston head by transforming the fuel’s potential energy into mechanical energy. The indicated diagrams for all analyzed regimes are presented in

Figure 5.

In [

11], the simulation results show a decrease in maximum cylinder pressure and an increase in ignition delay per cycle correlated with higher NH

3 fraction mixtures.

Figure 6 presents a decrease in power; at 70% load and 30% NH

3 mixtures, the engine lost 12.7% (10 kW), while on light load (10%), the difference increased to 47% (5.2 kW). BSFC has the same tendency; at 30% NH

3 and 10% load, the value increased by 88.9% (570.7 g/kWh), and at 70% load it increased by 14.5% (37.3 g/kWh). Pollutant emissions were reduced when higher fractions of NH

3 were used. For 30% NH

3, at the considered maximum load, NO

x decreased by 40.8% (790 ppm), and at 10% load, it decreased by 50.5% (180 ppm). At 30% NH

3 mixture and minimum load, soot decreased by 23.3% (0.05 g/kWh). Yuhan Zhou et al. [

12] proved that higher ammonia ratios, with up to a 60% ammonia energy ratio, lead to lower soot and NO

x emissions.

From the numerical simulations it can be concluded that the presence of ammonia in fuel blends has the biggest impact at the highest fractions (up to 30% NH

3).

Figure 6a shows the variation of engine torque and power by load for different NH

3 fractions. Engine power decreased by 12.7% at 70% load and 47.1% at 10% load. For efficiency evaluation, BTE and BSFC were used.

For the evaluation of BTE, when using diesel–ammonia mixtures, an equivalent lower heating value (LHV) that considers each fuel’s LVH was calculated:

where

%D and

%NH3 represent the mass fractions, and

QD QNH3 represent the LHV of each fuel, respectively.

The fuel consumption of the mixture is presented below as the sum of each component:

To evaluate the BTE and BSFC of the mixtures, the following formulas were used:

Figure 6b shows the variation of engine BTE and BSFC by load for different NH

3 fractions. BTE under the specified conditions decreased by up to 4.7% at low load but increased by 1.7% at high load with a 30% ammonia mass fraction. BSFC increased at heavy load (14.5%) and at the lightest load (88.9%). Although BSFC does not consider the equivalent lower heating value, the authors included it in the analysis, and the main parameter for efficiency evaluation was BTE.

Xuexuan Nie et al. [

13] studied the impact of ammonia substitution rates of up to 30% in a turbocharged diesel engine and found a decrease in both maximum cylinder pressure and BTE.

Figure 6c shows the variation of NO

x and soot emissions by load for different NH

3 fractions A beneficial effect could be seen on pollutant emissions, where NO

x dropped by 40.8% and soot by 13.4% under heavy load, while under light load, they dropped by 50.5% and 23.3%, respectively. The reduction in NO

x and smoke emissions can be explained by the decrease in peak fire temperature and the shortening of the total combustion duration per cycle, which in turn is caused by the reduced amount of available heat.

Air excess ratio (

λ) varies with the amount of NH

3 present in the engine. In

Table 4, simulated values are presented. A higher concentration of ammonia leads to a leaner fuel mixture.

5. Conclusions

It has been shown that direct injection of ammonia in combination with diesel fuel keeps engine performance within acceptable limits (13% lower) for ammonia mass fractions of up to 30%.

BTE under the specified conditions decreases by up to 4.7% at low load but increases by 1.7% at high load with a 30% ammonia mass fraction.

Although BSFC does not require the equivalent LHV of the mixture, the authors included it in the results. BSFC increases at heavy load by 14.5% and at the lightest load by 88.9%.

The presence of NH3 enables the simultaneous reduction in the studied pollutant emissions, with an acceptable decrease in engine power, accompanied by a slight reduction in BTE at low loads and an increase at high loads. NOx dropped by 40.8% and soot by 13.4% under heavy load, while under light load, they dropped by 50.5% and 23.3%, respectively.

The authors have begun to implement a multi-point injection system for ammonia in each cylinder of the tested engine. As for future work, they plan to perform a research study on the effects of ammonia injection timing and duration.