1. Introduction

Modern maritime security is increasingly threatened by a variety of activities, including illegal fishing, smuggling, and tactical infiltration. The emergence of small maritime objects and unmanned surface vehicles, such as inflatable boats, speedboats, and autonomous craft, has reshaped the operational landscape, particularly within the grey-zone domain where low-observability platforms and non-conventional tactics are employed to evade conventional surveillance. These strategies exploit the inherent limitations of current detection and classification systems, which rely heavily on visible-spectrum imaging, automatic identification system signals, and manual monitoring.

In adverse environmental conditions, such as fog, rain, darkness, and high sea states, these systems often suffer from missed detections, false alarms, and delayed decision-making, revealing systemic weaknesses such as non-real-time data flow and fragile sensing modalities. The dynamic nature of the maritime environment further increases the burden on both human operators and sensor infrastructures. To address these limitations, we developed an integrated surveillance architecture combining thermal imaging, deep learning-based object detection, and fuzzy logic inference. Designed for high-risk coastal zones, the proposed system enhances all-weather situational awareness, improves real-time responsiveness, and ensures robust target recognition. By embedding semantic inference and fault-tolerant mechanisms, the framework supports stable decision-making in uncertain and adversarial environments, offering a scalable solution for maritime domain awareness.

Recent thermal imaging research emphasizes the role of noise equivalent temperature difference and minimum resolvable temperature difference (MRTD) in influencing object detectability under maritime conditions [

1,

2]. In particular, powered vessels often yield clearer thermal contours, while low-emissivity targets remain challenging, necessitating preprocessing strategies such as contrast enhancement or noise reduction.

The You Only Look Once (YOLO) v8 model serves as the core recognition engine in this study due to its anchor-free architecture, enhanced residual modules, and strong performance in detecting small objects under thermal imaging conditions. Compared with its predecessors (YOLOv5–v7), YOLOv8 demonstrates superior inference speed, accuracy, and deployment efficiency, with validated use cases in traffic and maritime surveillance [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

The Johnson Criteria [

10] remains one of the most widely cited standards for detection, recognition, and identification (DRI) performance evaluation, emphasizing the role of spatial resolution—measured in cycles per target—in the three-stage DRI logic. While this study does not directly implement the parameterized MRTD approach [

11], relevant literature was reviewed to understand how MRTD curves relate to DRI range estimation and thermal imaging performance. Several studies [

1,

2] highlight the influence of thermal contrast and observation geometry on DRI accuracy, providing valuable insights for system calibration and design. In addition, the historical review of the Johnson Criteria [

12] outlines its evolution and addresses its applicability limits in modern sensing contexts.

To overcome the limitations of conventional object detection, especially under low-confidence or occluded conditions, we adopted fuzzy logic inference as a robust semantic reasoning framework. Using triangular membership functions and center of area (CoA) defuzzification, the system enables soft decision boundaries and improved interpretability. In maritime surveillance, this enhances AI stability under uncertainty and supports adaptive defense strategies in grey-zone scenarios [

13].

By integrating fuzzy inference as a core semantic reasoning mechanism, the proposed system architecture inherently supports both open set recognition and few-shot learning, enabling robust adaptation to operational uncertainty. Fuzzy logic facilitates soft decision boundaries and interpretable generalization from limited data, thereby reducing the dependence on large, predefined class sets. This flexibility is critical for open set recognition, where the system must identify and reject unfamiliar or novel objects—a common scenario in maritime surveillance involving emerging vessel types or anomalous behaviors. Furthermore, the fuzzified representation enhances few-shot learning by enabling the model to make informed decisions from sparse annotated instances, particularly in defense applications involving rare or covert targets. Together, these capabilities ensure resilient DRI assessments even in adversarial or unpredictable maritime conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Annotation and Methodology Design

We selected the following data annotation and preprocessing method for training domain-adaptive object detection models.

The proposed approach incorporates domain-specific characteristics of maritime thermal imaging and DRI tasks. By aligning with standard object detection practices while addressing operational constraints, the resulting workflow ensures high-quality, semantically consistent annotations suitable for robust model training and downstream fuzzy inference integration.

2.1.1. Thermal Imaging Data

To construct a representative thermal imaging dataset, we collaborated with the Maritime and Port Bureau, Ministry of Transportation and Communications, Taiwan, to collect thermal data during real-world vessel operations. The resulting dataset primarily consists of thermal imagery captured from the “Harbor 1” vessel under diverse operational scenarios. The collected images exhibit the following characteristics:

Temporal diversity: Scenes captured during daytime, nighttime, and dawn, covering different lighting conditions.

Dynamic diversity: Scenes classified as either static camera (e.g., docked ships, fixed monitoring) or moving camera (e.g., during navigation).

Weather and visibility conditions: Including clear skies, overcast, low visibility, backlighting, and fog/rain environments.

All images are encoded by timestamp and labeled by mission type to ensure consistency and traceability in subsequent annotation and training.

2.1.2. Annotation Workflow and Quality Assurance

To support robust object detection training, a structured annotation workflow was developed with an emphasis on semantic consistency and boundary precision. Video data were collected under diverse maritime conditions and categorized based on scene dynamics. For static scenes (e.g., docking), frames were extracted every 1800 frames (static scenes) and every 30 frames (dynamic scenes) was used to capture temporal variability. Extracted frames were archived by source video and uploaded to a centralized NAS.

Annotations were performed manually using the Labelme tool, targeting thermal object contours via polygon-based labeling. A three-tier quality assurance strategy was implemented: (1) task allocation to trained research assistants, (2) dual-person cross-validation to verify semantic consistency and completeness, and (3) weekly quantitative assessments by the core team using metrics such as intersection-over-union (IoU) and label consistency rate.

Upon completion, annotations were converted from JavaScript Object Notation to YOLOv8-compatible .txt format through a custom parser, enabling downstream model training and fuzzy inference integration. This reproducible pipeline ensures high-quality, semantically valid labels while balancing scalability and annotation efficiency.

2.2. Model Training

The object detection training model was developed to address the challenges of maritime thermal imagery, such as low contrast, small object scale, and frequent occlusions. YOLOv8n was selected for its balance between real-time inference and deployment feasibility. To enhance robustness across operational scenarios, the dataset was stratified by environmental conditions (e.g., day/night, clear/foggy), and augmented using standard transformations (e.g., flipping, cropping, scaling) alongside photometric perturbations to simulate varying thermal contrast. Occlusion effects, such as fog and water glare, were further modeled using custom mosaic and masking strategies to improve generalization under real-world interference.

Training was conducted with fine-tuned pretrained YOLOv8n weights using the Adam optimizer and cosine annealing. A calibrated IoU threshold was introduced to enhance small-object detection performance. Model effectiveness was evaluated using mean average precision (mAP), precision-recall curves, and confusion matrices, with a particular focus on low signal-to-noise ratio and occluded scenes. This domain-adaptive training configuration provides the foundation for integrating downstream fuzzy inference modules, enabling robust and interpretable DRI estimation under complex maritime conditions.

2.2.1. Training Data Preparation and Splitting Strategy

Upon completion of the annotation workflow, a diverse thermal imaging dataset was constructed, covering various scenes, time periods, and weather conditions, including daylight, nighttime, backlighting, fog, and both static and dynamic camera views. The dataset was partitioned according to standard deep learning practices, as follows:

Training set (80%): Used to optimize model weights.

Validation set (10%): Used to monitor convergence and prevent overfitting.

Test set (10%): Used to evaluate the model’s generalization performance on unseen data.

2.2.2. Model Architecture: YOLOv8n

Training was conducted using the Anaconda platform with compute unified device architecture-enabled NVIDIA graphics processing unit (GPU) and the PyTorch 2.10.0 framework. YOLOv8n, a lightweight model incorporating anchor-free design, C2f modules, and a decoupled head, was selected to balance detection performance and deployment feasibility. Pretrained weights were fine-tuned on the thermal dataset to enhance recognition under limited data conditions. The loss function integrates classification, localization (complete IoU (CIoU)), and objectness terms, jointly optimized through backpropagation. Training dynamics were monitored via loss convergence curves to assess learning stability and generalization.

To improve robustness under low-contrast and occluded conditions, domain-adaptive augmentation strategies were implemented, including photometric distortion, geometric transforms, and occlusion simulation via custom masking techniques. These augmentations were integrated directly into the training pipeline to enhance generalization across diverse maritime scenarios.

2.2.3. Hyperparameter

To ensure convergence and training stability, the model was trained for 100 epochs using an initial learning rate of 0.01 with cosine decay scheduling. The batch size was set to 16 and adjusted based on available GPU memory, while momentum (0.937) and weight decay (0.0005) were applied to enhance convergence dynamics and mitigate overfitting. Input image resolution was standardized at 640 × 640. An early stopping criterion with a patience of 10 epochs was implemented to prevent overfitting and reduce unnecessary computational overhead. All hyperparameters followed YOLOv8 default settings unless otherwise noted.

2.2.4. Training Stabilization and Overfitting Mitigation

Given the relatively small and thermally heterogeneous dataset, the overfitting risk was non-trivial. To address this, early stopping was triggered upon validation stagnation across 10 consecutive epochs. L2 weight decay (λ = 0.0005) and a Dropout ratio of 0.3 were applied to suppress co-adaptation and improve generalization. Continuous tracking of loss, mAP, precision, and recall was performed to monitor training convergence and divergence trends. Checkpoints were saved every 10 epochs and archived to a centralized NAS for performance traceability and ablation comparison. This monitoring pipeline proved essential in maintaining model robustness, especially under variable maritime imaging conditions.

2.3. Fuzzy Logic-Based Robust DRI Inference

Analysis results of the collected thermal dataset revealed limitations in using spatial resolution (cycles per target) as the sole criterion for DRI. For example, two vessels—a cargo ship (approximately 100 m in length) and a ferry (approximately 17 m in length)—were assigned bounding boxes of similar pixel dimensions by the model. This occurred because the ferry was closer to the camera while the cargo ship was farther away, resulting in a comparable apparent size in the thermal image despite their substantial differences in physical dimensions and distances.

2.3.1. Fuzzy Modeling for Multi-Parameter DRI Inference

Through in-depth analysis, it was found that DRI inference is inherently limited and prone to misjudgment relying on any single variable, such as confidence score, bounding box screen ratio, or estimated distance [

14,

15,

16]. To overcome this, a fuzzy logic framework was adopted to integrate multi-source object detection features into interpretable DRI assessments under uncertainty, providing a fault-tolerant alternative to threshold-based methods.

2.3.2. Selection and Fuzzification of Premise Variables

To enhance the interpretability and reliability of DRI estimation under uncertainty, three key features derived from object detection outputs were selected as premise variables for fuzzy inference.

Confidence score (from YOLOv8 predictions), representing detection reliability;

Screen ratio, defined as the area of the bounding box normalized by image size, indicates visual prominence;

Estimated distance, computed via a monocular geometric algorithm incorporating camera height, field of view, and object scale [

17].

For each feature, fuzzy membership functions were constructed using a hybrid approach based on both statistical analysis and physical interpretation.

Distribution analysis (e.g., histograms, cumulative distribution functions, interquartile range) was conducted to identify natural breakpoints and define universe of discourse (e.g., low, medium, high).

To avoid semantic mismatches, domain knowledge was applied to adjust boundaries. For instance, although confidence scores below 0.5 are statistically valid, they are often too uncertain to support meaningful recognition, and thus are categorized as Low. Similarly, distance thresholds were adjusted to match maritime risk assessment (e.g., <200 m as Near).

This dual-layered method ensures that fuzzy variables retain both data-driven reliability and domain-driven semantic validity, enabling robust, explainable, and operationally meaningful fuzzy rule construction for downstream DRI decision logic.

3. Results

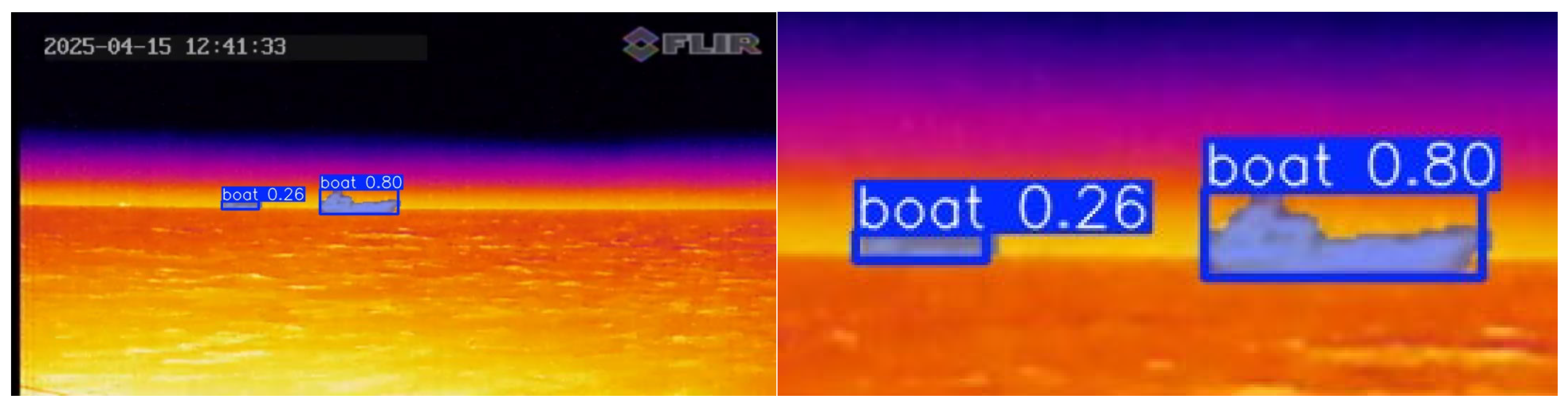

To determine appropriate universe of discourse for the premise variables, we analyzed the current thermal imaging dataset in detail. Focusing on the confidence score, results from the trained YOLOv8 model indicate that predictions below 0.5 are frequently linked to unrecognizable features or misclassifications. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the vessel on the right, with sufficient pixel coverage, is accurately identified as a ship with a confidence score of 0.8. In contrast, the vessel on the left, appearing much smaller due to its greater distance, exhibits limited visual features, leading the model to assign a significantly lower confidence score of 0.26.

Based on the results, a confidence score of 0.5 was adopted as a reference value for defining the universe of discourse. The resulting membership function is defined as follows:

Low: Confidence score in the range of 0.00–0.50.

Medium: Confidence score in the range of 0.20–0.80.

High: Confidence score in the range of 0.50–1.00.

The overlapping intervals in universe of discourse facilitate interpretability of fuzzy inference.

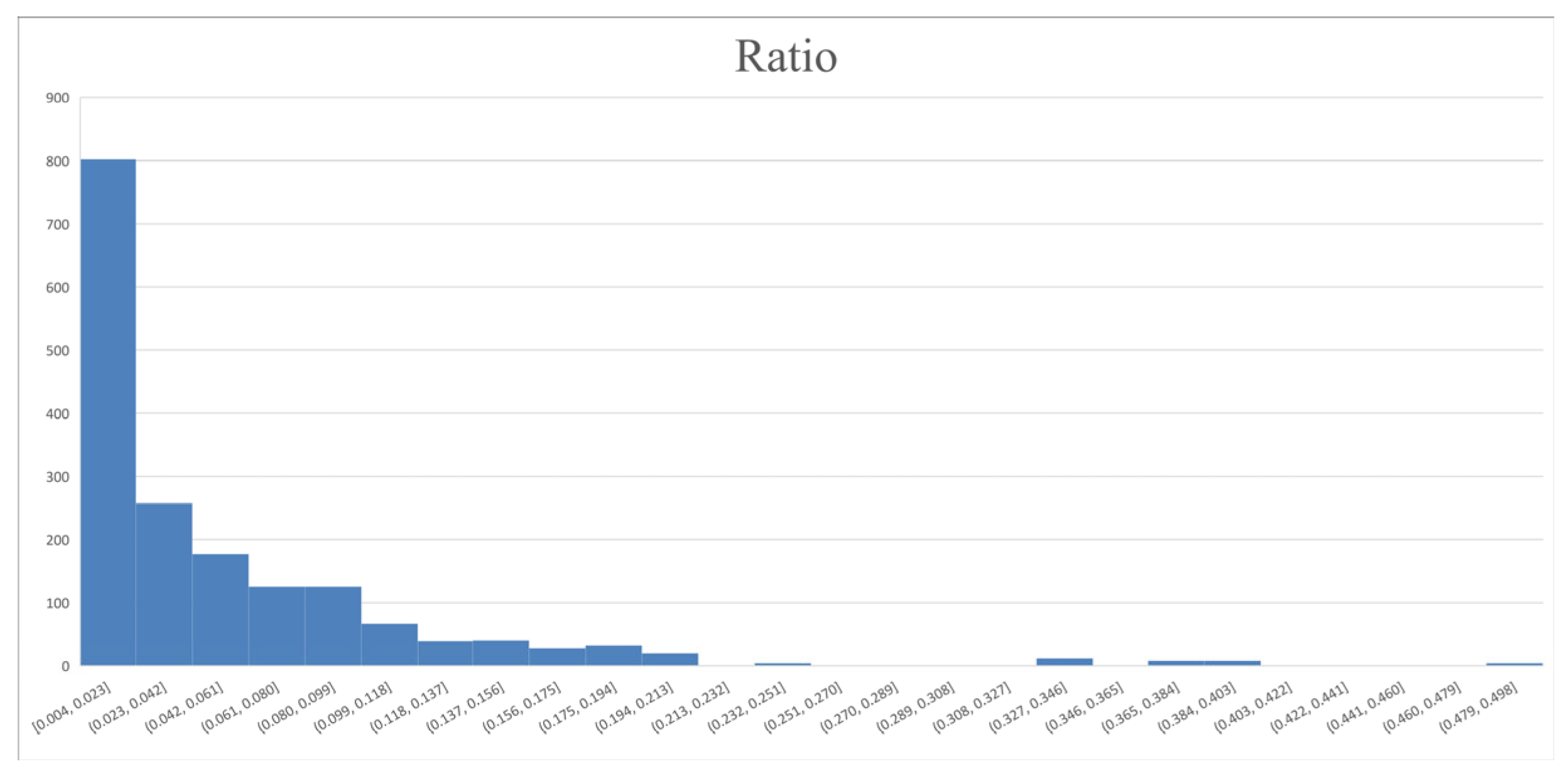

Subsequently, based on the annotated results obtained through the aforementioned training and data quality strategies, the screen ratio of bounding boxes was statistically analyzed with respect to spatial resolution (i.e., cycles per target). The results were visualized as a sorted distribution chart, illustrating the variation in object image scale from smallest to largest, as shown in

Figure 2. The screen ratio of the annotated bounding boxes ranges from approximately 0.01 to 0.5 (on the

x-axis). Accordingly, the universe of discourse for this feature were defined as follows, with the corresponding membership function:

Low: Bounding box occupies 0.001–0.05 of the screen area.

Medium: Bounding box occupies 0.01–0.1 of the screen area.

High: Bounding box occupies 0.05–0.5 of the screen area.

Figure 2.

Bounding box area statistics (x-axis: bounding box screen ratio; y-axis: count).

Figure 2.

Bounding box area statistics (x-axis: bounding box screen ratio; y-axis: count).

Based on the estimated relative distance between the navigating vessel and maritime targets, distance intervals were defined to support semantic fuzzy inference. The corresponding membership function is defined as follows:

Near: Distance between 0 and 500 m.

Medium: Distance between 200 and 700 m.

Far: Distance between 500 and 1000 m.

These intervals in universe of discourse provide a domain-aware basis for classifying target proximity under real-world operational conditions.

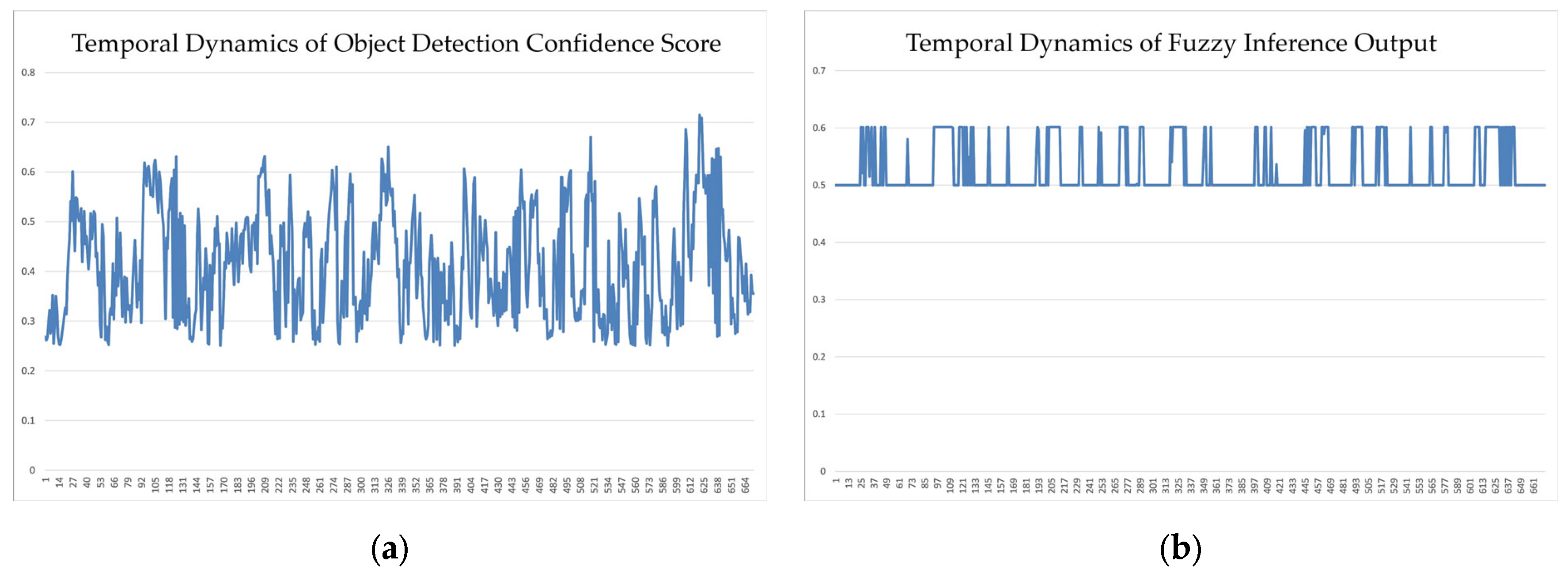

Figure 3 demonstrates that relying solely on the confidence score for maritime object detection can lead to unstable or fluctuating recognition outputs, particularly under low-visibility or occluded conditions. In contrast, the proposed fuzzy inference framework that which integrates confidence score, screen ratio, and estimated distance as premise variables, produces significantly stable and semantically consistent detection outcomes. By leveraging multi-parameter fusion, the fuzzy logic system compensates for weaknesses in individual features, yielding robust DRI assessments even when one or more inputs exhibit uncertainty. This confirms the advantage of fuzzy reasoning in enhancing the reliability and interpretability of object recognition in complex maritime environments.