Abstract

Multi-material Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Additive Manufacturing (AM) processes enable the integration of different material properties into a single structure, addressing the requirements of various applications and working environments. Laser-based Directed Energy Deposition (DED-LB) has been employed in the past for surface coatings as well as for the repair and repurposing of high-value industrial components, with the goal of extending product lifetime without relying on expensive and time-consuming manufacturing from scratch. While powder DED-LB has traditionally been used for multi-material AM, the more resource-efficient and cost-effective wire DED-LB process is now being explored as a solution for creating hybrid materials. This work focuses on the critical aspects of implementing multi-material DED-LB, specifically defining an optimal operating process window that ensures the best quality and performance of the final parts. By investigating the possibility of combining stainless steel and nickel-based alloys, this study seeks to unlock new possibilities for the repair and optimization of naval components, ultimately improving operational efficiency and reducing downtime for critical naval equipment. The analysis of the experimental results has revealed strong compatibility of stainless steel 316 with Inconel 718 and stainless steel 17-4PH, while the gray cast iron forms acceptable fusion only with stainless steel 17-4PH. Finally, during the experimental phase, substrate pre-heating and process monitoring with thermocouples will be employed to manage and assess heat distribution in the working area, ensuring defect-free material joining.

1. Introduction

Multi-material metal Additive Manufacturing (AM) is the process of combining different materials in a unique structure [1,2,3]. The produced end parts are called bimetallic, trimetallic, etc., components, depending on the number of materials used [2]. These components are adopted increasingly from the industrial world since they can lead to economic benefits (e.g., repair) and end-part performance advantages (e.g., coatings) [4,5].

In the past, multi-metallic components were developed through casting, explosive welding, diffusion joining and powder metallurgy [6,7,8]. However, their process mechanisms have been linked with poor mechanical properties due to high residual stresses caused by continuous thermal cycles throughout the entire geometry, distortion and intrinsic defects, extensive post-machining and low flexibility in terms of geometry [2]. These challenges have steered the industries to explore multi-material metal AM.

Although metal AM does not match the speed and cost efficiency of conventional mass production methods, it provides a viable solution for low-production volume manufacturing (replacement parts, casting parts) while it supports repair processes [1,9]. Compared to traditional repair with arc-based welding, laser-based metal AM provides focused heat input, contributing to narrow heat affected zone and controlled thermal cycles reducing the thermal gradients and distortions [10]. Billions of dollars are spent annually repairing and replacing metal parts due to corrosion or/and wear. Approximately 30% of the associated costs and downtime could be reduced by accelerating the adoption of metal additive manufacturing [9].

The laser-based Directed Energy Deposition (DED-LB) processes can support repair and repurpose processes by joining different materials with very similar material properties and microstructure. In practice, multi-material processes can be achieved in several ways. Powder-based DED-LB systems use multiple hoppers to feed different materials into the melt pool, allowing either in situ mixing or discrete deposition [11]. The latter applies also to wire DED-LB systems, switching the feedstock layer-by-layer or region-by-region, based on the part’s specifications [12]. However, the in situ mixing of material introduces challenges as it regards the process stability and the expected part’s properties [13].

Most of the recorded repair scenarios combine stainless steel and nickel-based alloys. Both material families can cover significant requirements, being compatible with many other metals. On the other hand, they are inserting significant challenges in conventional material removal-subtractive processes. Steel alloys have been used mainly for repairing mold dies and tools, vessels, crankshafts, driveshafts, engine pistons, etc. Nickel-based alloys have been selected for the repair of gas turbines on the compressor seal, turbine blades and airfoils, thin-curved fins of propellers, etc. However, the application of DED is not limited in those materials, but it can be used in any weldable material considering the appropriate choice of heat input type. For the repair of Ti-6Al-4v and Inconel 718 alloys, stainless steel has been used while nickel-based alloys are also preferred for the repair of components made by copper [2]. In an example that comes from the energy sector (wind power equipment), a large-scale component that was made of steel is now being repaired by adding Inconel 625, aiming to improve its surface properties and elongate its lifetime.

Scope of This Work

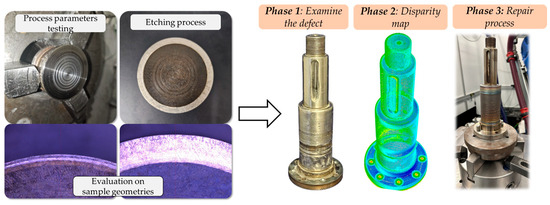

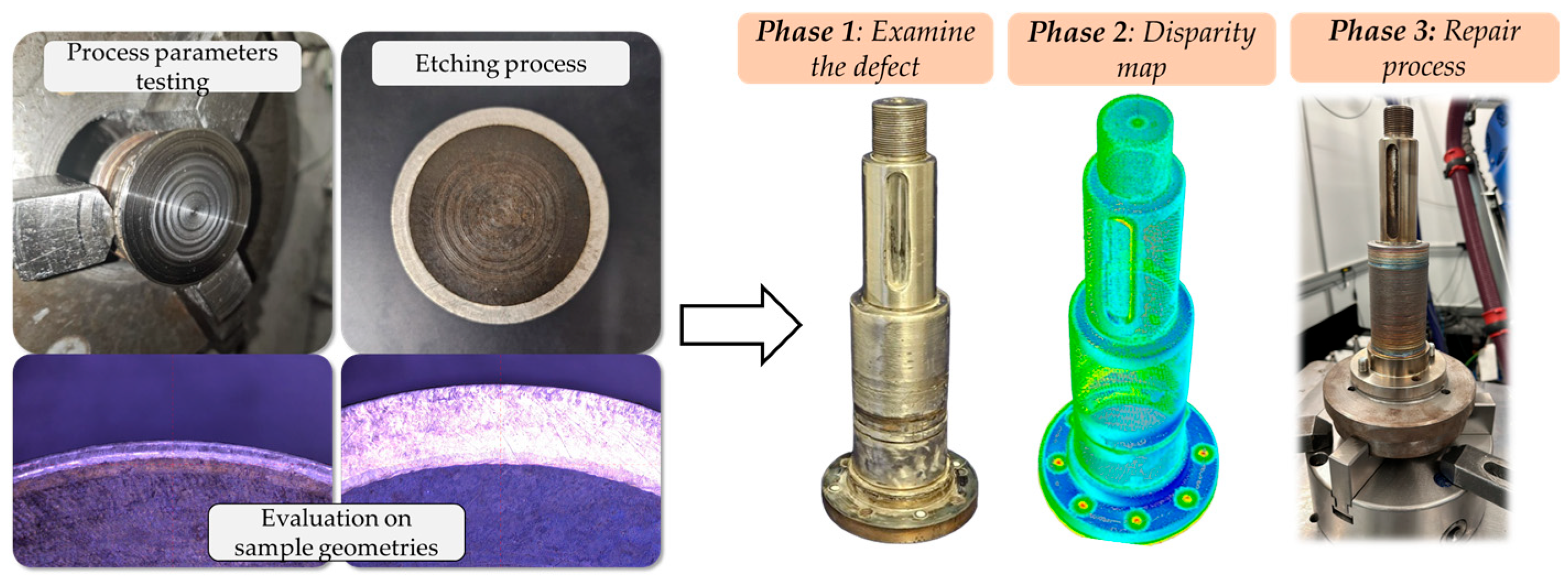

In this work, the existing knowledge from well-documented materials in the field of metal AM is used to guide the selection of working parameters for various materials based on their thermophysical properties and their chemical composition. For this experimental work a wire laser-based Directed Energy Deposition (DED-LB) system is used. The laser power, wire feed rate, deposition head speed and the substrate temperature vary, and their effect on the penetration depth, wetting and porosity as well as on the formation of pores and cracks is evaluated. The combination of parameters that are used for the deposition of stainless steel 316 (SS316) on a substrate of the same material guide the selection of the process parameter values when Inconel 718 (IN718) and stainless steel 17-4PH (SS17-4PH) are deposited on SS316 substrate. All the materials have been provided by the MELTIO (Linares, Spain) company. The same methodology is followed when the base material is a gray cast iron (GCI). In the latter case, apart from the three mentioned feedstock materials, the SS316 is also deposited. These combinations of materials have been selected based on the needs of naval industry.

The structure of the current work is presented hereafter. Section 2 presents the experimental set up while Section 3 delivers the methodology towards the selection of the process parameter values based on the material characteristics while also introducing the combination of the investigated parameters. The results are discussed in Section 4 while in Section 5 the methodology is evaluated based on an actual case-study from naval industry. The conclusions and future remarks are included in Section 6.

2. Experimental Set Up

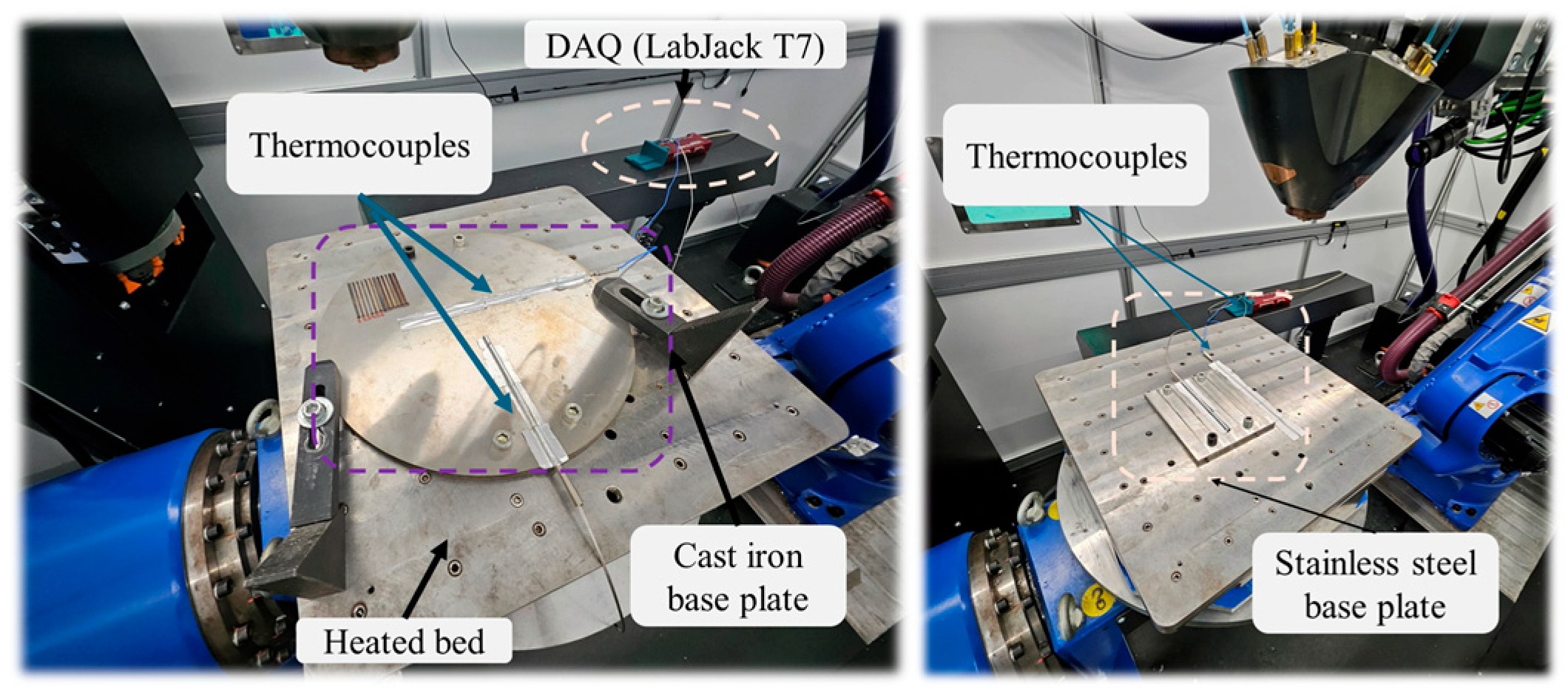

A MELTIO (Linares, Spain) DED-LB head system with six off-axis, infrared laser beams (976 nm) and coaxial wire feeding mechanism is used. The laser spot size for each of the beams is 0.4 mm. The shape of the laser beams at the surface can be simulated to a hexagon, with more than 50% overlap between the beams. The Stand-off Distance (SoD) is set to 6 mm, being defined as the distance between the tip of the wire nozzle and the substrate upper surface. Throughout the experimental work, the inert gas (Argon) was maintained at a constant rate of 8 L/min. The feedstock diameter for all the studied materials was measured around the nominal value of 1 mm (±0.1 mm). The system is equipped with a heated table. A resistance for heating covers the lower surface of the working table. The temperature is controlled based on the feedback from the thermocouples which are located close to the working area and at the substrate. Probe-based, type J, thermocouples were preferred to capture the temperature across the working area instead of the wire-based thermocouples that record the temperature on a spot. Data acquisition and denoising was executed via a LabJack DAQ (T7 PRO) platform. Then, the data were transmitted via USB port to a computer which was interacting via Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) with the robot and DED controller.

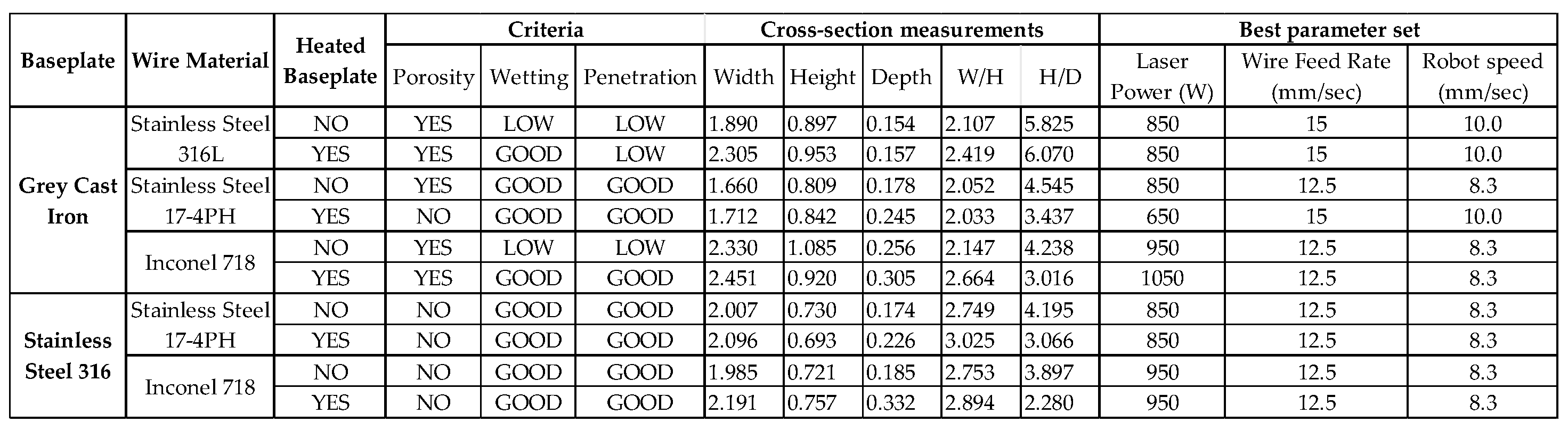

Throughout this work, three substrate plates were used. Two of them were made by SS316 and the third one was made by GCI. The substrate thickness was 10 mm. The experimental set up is depicted in Figure 1. The discussion about the material choice for the feedstock and the substrate is provided in Section 3. Lastly, an Insize (Derio, Spain) ISM-DL301 optical microscope was used to reveal bead dimensions after etching.

Figure 1.

Experimental set up and substrate materials.

3. Experimental Work

The end-users are interested in achieving improved performance by leveraging the laser-based DED process mechanism and the customized mechanical properties of the fabricated parts [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. However, as regards the repair processes, significant challenges occur during the investigation of compatible feedstock and base materials.

In the literature, compatibility matrices of various metals can be found. In practice, during the process planning of a repair or repurpose scenario, the engineer should identify the appropriate filler material after performing metallography analysis of the base material. Moreover, the engineer selects the processing parameters after performing a multi-purpose experimental workflow in single tracks to extract the level of penetration. The penetration depth appears after time-consuming polishing and etching. Single tracks are deposited throughout this investigation to reduce the number of geometrical-dependent parameters, while enabling fast-executed experiments.

Although this workflow can provide a variety of working parameters, the challenge of combining two different materials can appear when multi-layer parts are being fabricated. The challenges are linked to their thermophysical properties and their behavior during thermal cycles. However, these details are geometry dependent, exceeding the scope of the present work.

3.1. Material Characteristics

Throughout this work, stainless steel and nickel-based alloys are investigated with regard to being used by naval, energy and aeronautical sectors as well as mold-making industries. Good corrosion resistance and excellent mechanical strength are achieved by refining the grain structure and reducing residual stresses with the aid of heat treatment. As an example, the aging cycles of parts made or repaired by SS 17-4PH dictate its hardness and tensile strength [17,18]. The heat treatment cycles and the treated area should be determined based on the desired part’s mechanical and surficial properties as well as the thickness of the deposited material. Below, few characteristics of the selected materials are introduced.

- IN 718: It is a Nickel–Iron–Chromium-based-alloy which maintains its material properties up to 700 °C, presenting very good corrosion resistance. It is used in turbine engines, components of vessel engines as well as in nuclear engineering [16,17,18].

- SS316: It is an austenitic Chromium–Nickel–Molybdenum alloy known for its excellent corrosion resistance, which maintains good mechanical properties up to 600 °C. It is used in chemical processing, marine components and medical devices, etc. [9,17].

- SS 17-4 PH: It is a precipitation-hardening martensitic stainless steel that offers a combination of high strength, good corrosion resistance and excellent dimensional stability. It can maintain these properties up to temperatures around 480 °C and is widely used in aerospace, energy and tooling applications.

- GCI: It is a ferrous alloy characterized by the presence of graphite flakes in its microstructure, giving it excellent damping capacity, good machinability and compressive strength. However, it exhibits poor weldability due to its high carbon content. GCI is used in engine blocks, machine bases and structural components. Tailored heat treatments can help reduce residual stresses and improve microstructural integrity [17,18].

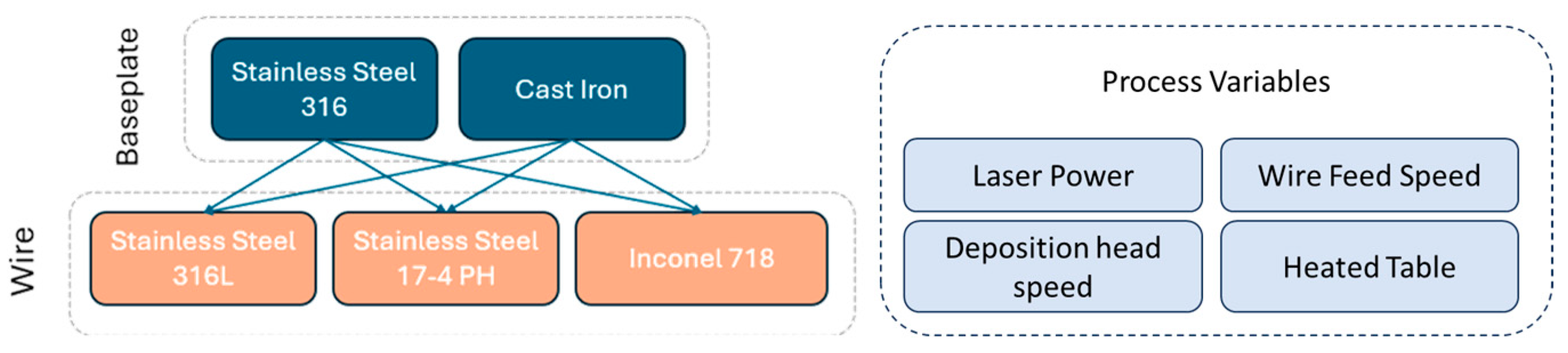

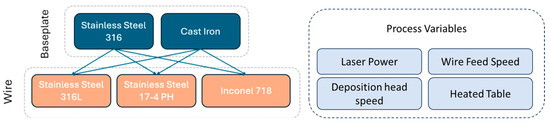

The combination of materials is depicted in Figure 2, dividing the filler and substrate material. The material combinations studied are made up of four combinations for the GCI and three for the SS substrates.

Figure 2.

Combination of substrate and filler material.

3.2. Design of Experiments

The variable process parameters are those with the most prominent effect on part quality (Figure 2)—laser power (P), deposition head speed (v), wire feed rate (WFR) and substrate preheat temperature. The rest of the parameters remained constant across all experiments (shielding gas flow rate, spot size, working distance and beam shape). WFR value depends on v to always match the ratio 1.5:1 (WFR to be 1.5 times v), as it is proven to be a ratio that consistently provided good results in previous experiments [19].

Due to the absence of documentation on multi-material AM in wire DED-LB and complex-to-model thermodynamic phenomena, the selection of process parameters is based on successful parameter sets of SS316 wire and substrate and they are adjusted based on the thermal properties of the material that is used as feedstock and base. The investigated thermal properties are the liquidus temperature, thermal conductivity, specific heat capacity, thermal diffusivity and coefficient of thermal expansion. For each combination, the energy input and the linear energy density are adjusted based on the effect of these properties on heat absorption as it is documented in the literature [20]. As an example, if the liquidus temperature, specific heat capacity and thermal diffusivity of the investigated material exceed those of SS316, the linear energy density (more heat input over a specified length) should also be increased, while if the thermal conductivity is increased, the energy density should be reduced (less heat input over a specified length). Preheating is mandatory in the case of depositing on metals with high thermal expansion coefficients or in metals that are susceptible to cold cracking (e.g., GCI). Conversely, the hot cracking cannot be avoided with pre-heating since it is directly linked to the material chemical composition. Preheating the substrate is also beneficial in reducing porosity and cold cracking, as it reduces residual stresses [20]. Reflectivity can also influence the heat input. A more reflective surface requires higher energy density to achieve the same effect as a less reflective surface. The reflectivity of SS316 is noticeably higher than gray cast iron; thus, decreased energy density is required when using the latter.

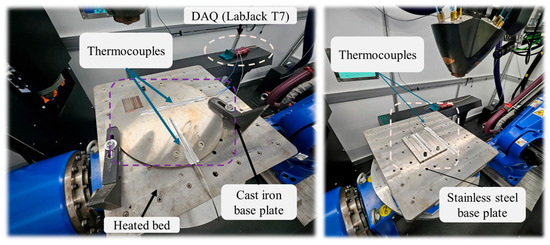

The tested parameters are summarized in Table 1. For each material combination 12 experiments were conducted, 6 experiments with pre-heated table and 6 experiments at room temperature. The pre-heat temperature of the bed was set at 200 °C. In total, five combinations were tested (Figure 2) resulting in 60 experiments in total (Table 1).

Table 1.

Combination of process parameters for multi-material AM investigation.

4. Results and Discussion

After the deposition, the specimens were labeled and sectioned at the middle where the bead geometry is stabilized [20]. The two sides of the section were measured, providing identical values. The specimen’s cross section was polished and etched by using aqua regia etchant for SS316 substrate and Nital etchant for GCI revealing the penetration depth, the wetting, as well as some inclusions.

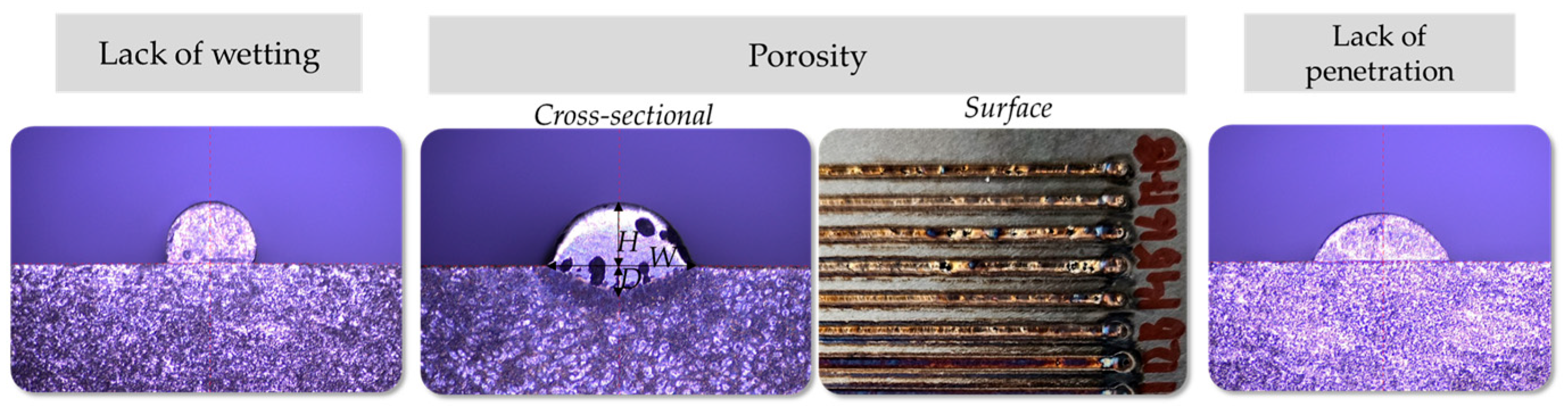

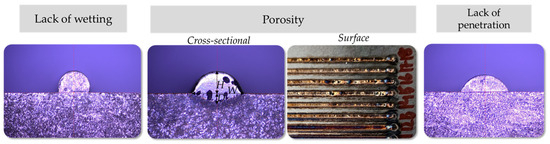

Failure Criteria-Performance Indicators

The quality of the deposited bead is assessed using the width-to-height (W/H) ratio. This ratio evaluates the shape of the bead above the build plate. In the literature, an optimal ratio around three has been identified [20]. In addition to geometric considerations, wetting is a critical criterion which determines structural integrity by indicating the fusion between the deposited material and the substrate. The presence of macro-porosity or/and cracks on the bead is considered unacceptable, regardless of its size. Each of these defects are seen in Figure 3 while in Figure 4 the effect of pre-heat on bead quality is presented.

Figure 3.

Failure criteria, lack of wetting, porosity, lack of penetration.

Figure 4.

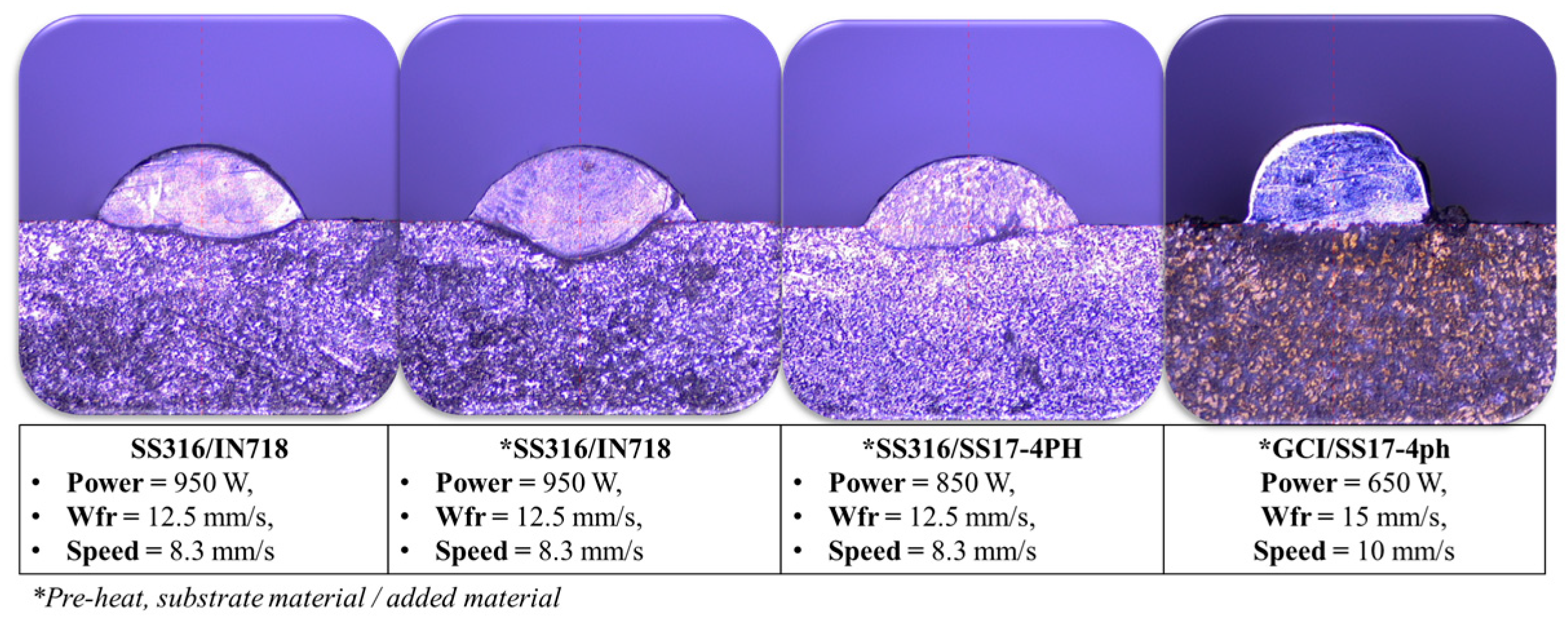

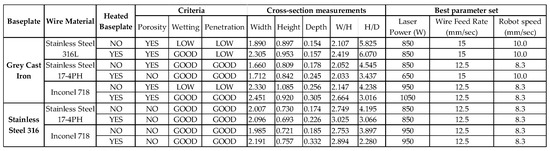

Measurements and comparison of the best track for each metal combination.

The experiments provided valuable insights into the compatibility of the investigated materials. Specifically, the tracks deposited on GCI plate present uneven interface between the substrate and deposited feedstock. Macro-pores along the interface line were detected. This is probably due to the inclusions and impurities found in GCI, forming gas bubbles within the melt pool while the waviness can be attributed to the difference in density of the two metals [20]. It is noted that preheating is beneficial for the GCI substrate experiments since it contributes to reduced thermal gradients, effectively reducing porosity, cracking tendency and achieving greater penetration depth.

- GCI–SS316: In this combination, low wetting and penetration depth as well as complete lack of fusion in the case of low energy density (P: 650 W, v: 10 mm/s) experiments with and without preheating has been identified. Preheating has contributed to improving the wetting and W/H ratio. However, macro-pores were detected.

- GCI–SS17-4PH: One acceptable parameter set was identified (P: 650 W, v: 10 mm/s), demonstrating the compatibility of these two materials. Table pre-heat contributed to higher penetration depth and thus to a successful set of parameters. Both scenarios are pore-free. This set will also be tested in solid structures with various path planning strategies, following the guidelines for the cold welding of GCI [20].

- GCI–IN718: No acceptable parameter sets were found. Extreme porosity and surface waviness is present in all tracks with and without preheat. Preheating has increased penetration depth and bead width while it has led to improved wetting.

- SS316–SS17-4PH: Adequate compatibility was achieved. Two acceptable parameter sets without preheated table (P: 850 W, v: 8.3 mm/s, P: 850 W, v: 10 mm/s) and three with preheated (P: 750 W, v: 8.3 mm/s, P: 850 W, v: 8.3 mm/s, P: 850 W, v: 10 mm/s) were found. These results are expected due to the relatively close material properties and chemical composition of the studied materials.

- SS316–IN718: Two acceptable parameter sets have been identified in the case of not preheating the table (P: 950 W, v: 8.3 mm/s, P: 1050 W, v: 10 mm/s) and two more sets when the table has been preheated (P: 950 W, v: 8.3 mm/s, P: 1050 W, v: 8.3 mm/s). Preheating leads to increased bead width and penetration depth.

Finally, the optimal combinations of parameters for the various combinations of materials and the relative bead dimensions and shape are given in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Successful set of parameters for the investigated combination of materials.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This work delivers a structured workflow on the identification of working parameters for a combination of materials based on the understanding of their material properties. Five material combinations were studied. At least one successful set was identified for the cases where the SS316 is used as substrate and only one filler material was found (SS 17-4PH) to be compatible with the GCI plate. The workflow was validated in a case study from the naval industry by depositing SS 316 on duplex stainless steel. The findings of this work can be used to guide future research on this topic with significant industrial adoption, especially in the repair and repurposing application area:

- Microstructure investigation (grain size and morphology) at the interface between the bonded metals to provide further insights about the grains and their morphology.

- Development of thin walls and solid structures to evaluate the effect of the thermal cycles on the interface microstructure.

- Study the effect of preheating methods (e.g., coils, laser) on bead shape and geometry.

- The addition of a third intermediate layer (tri-metallic joining) with a metal of higher compatibility with the other two metals to improve joining.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and K.T.; methodology, K.T. and N.P.; software, K.T. and N.G.; validation, P.S. and K.T.; formal analysis, N.G.; investigation, N.P. and N.G.; resources P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G. and N.P.; writing—review and editing K.T., N.G. and P.S.; visualization N.P. and K.T.; supervision, P.S.; project administration, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This research has been partially supported by EIT Manufacturing and co-funded by the European Union (EU), through project (TF Knownet+), ID 24235.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stavropoulos, P. AM Applications. In Additive Manufacturing: Design, Processes and Applications; Springer Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekh, M.; Yeo, L.C.; Bair, J.L. A review of 3D-printed bimetallic alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 4191–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, A.; Aversa, A.; Marchese, G.; Biamino, S.; Lombardi, M.; Fino, P. Application of Directed Energy Deposition-Based Additive Manufacturing in Repair. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leino, M.; Pekkarinen, J.; Soukka, R. The Role of Laser Additive Manufacturing Methods of Metals in Repair, Refurbishment and Remanufacturing—Enabling Circular Economy. Physics Procedia 2016, 83, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Kapil, A.; Klobčar, D.; Sharma, A. A Review on Multiplicity in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Process, Capability, Scale, and Structure. Materials 2023, 16, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Onuike, B. Additive Manufacturing of Bimetallic Structures. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2022, 17, 256–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Wu, G.Q.; Huang, Z.; Ruan, Z.J. Diffusion Bonding of Laser Surface Modified TiAl Alloy/Ni Alloy. Mater. Lett. 2004, 58, 3470–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.A.; Dewan, M.W.; Huggett, D.J.; Okeil, A.M.; Liao, T.W.; Nunes, A.C. Challenges in the Detection of Weld-Defects in Friction-Stir-Welding (FSW). Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 5, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porevopoulos, N.; Tzimanis, K.; Souflas, T.; Bikas, H.; Panagiotopoulou, V.C.; Stavropoulos, P. Decision Support for Repair with DED AM Processes Based on Sustainability and Techno-Economical Evaluation. Procedia CIRP 2024, 130, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagalingam, A.P.; Shamir, M.; Tureyen, E.B.; Sharman, A.R.C.; Poyraz, O.; Yasa, E.; Hughes, J. Recent progress in wire-arc and wire-laser directed energy deposition (DED) of titanium and aluminium alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 2035–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, B.; O’Neil, A.; Sahasrabudhe, H. Microstructural and Mechanical Characterization of Stainless Steel 420 and Inconel 718 Multi-Material Structures Fabricated Using Laser Directed Energy Deposition. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 68, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureña, J.; Alvarez-Leal, M. Microstructural and Hardness Characterization of Stainless Steel 316–Inconel 718 Multimaterial Developed by Wire-Based Directed Energy Deposition. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 135, 2975–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelz, J.S.; Ku, N.; Shoulders, W.T.; Meyers, M.A.; Vargas-Gonzalez, L.R. Multi-material additive manufacturing of functionally graded carbide ceramics via active, in-line mixing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Video: AM for Repair of Large Shafts. Available online: https://www.additivemanufacturing.media/articles/video-am-for-repair-of-large-shafts (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Saboori, A.; Aversa, A.; Marchese, G.; Biamino, S.; Lombardi, M.; Fino, P. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AISI 316L Produced by Directed Energy Deposition-Based Additive Manufacturing: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, P.; Pastras, G.; Tzimanis, K.; Bourlesas, N. Addressing the challenge of process stability control in wire DED-LB/M process. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3D Metal Printing Saves Time and Lowers Costs: DED for Repair. Available online: https://optomec.com/how-3d-metal-printing-saves-time-and-lowers-costs-ded-for-repair-of-industrial-components/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Guidelines for Welding Cast Iron. Available online: https://www.lincolnelectric.com/en/welding-and-cutting-resource-center/welding-how-tos/guidelines-for-welding-cast-iron (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Unitor Welding Handbook–Welding and Related Processes for Repair and Maintenance Onboard (14th ed., 2nd Rev.). Available online: https://www.wilhelmsen.com/globalassets/ships-service/welding/documents/wilhelmsen-ships-service---unitor-welding-handbook.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Pilagatti, A.N.; Atzeni, E.; Salmi, A.; Tzimanis, K.; Porevopoulos, N.; Stavropoulos, P. Knowledge Generation of Wire Laser-Beam-Directed Energy Deposition Process Combining Process Data and Metrology Responses. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).