A Three-Stage Transformer-Based Approach for Food Mass Estimation †

Abstract

1. Introduction

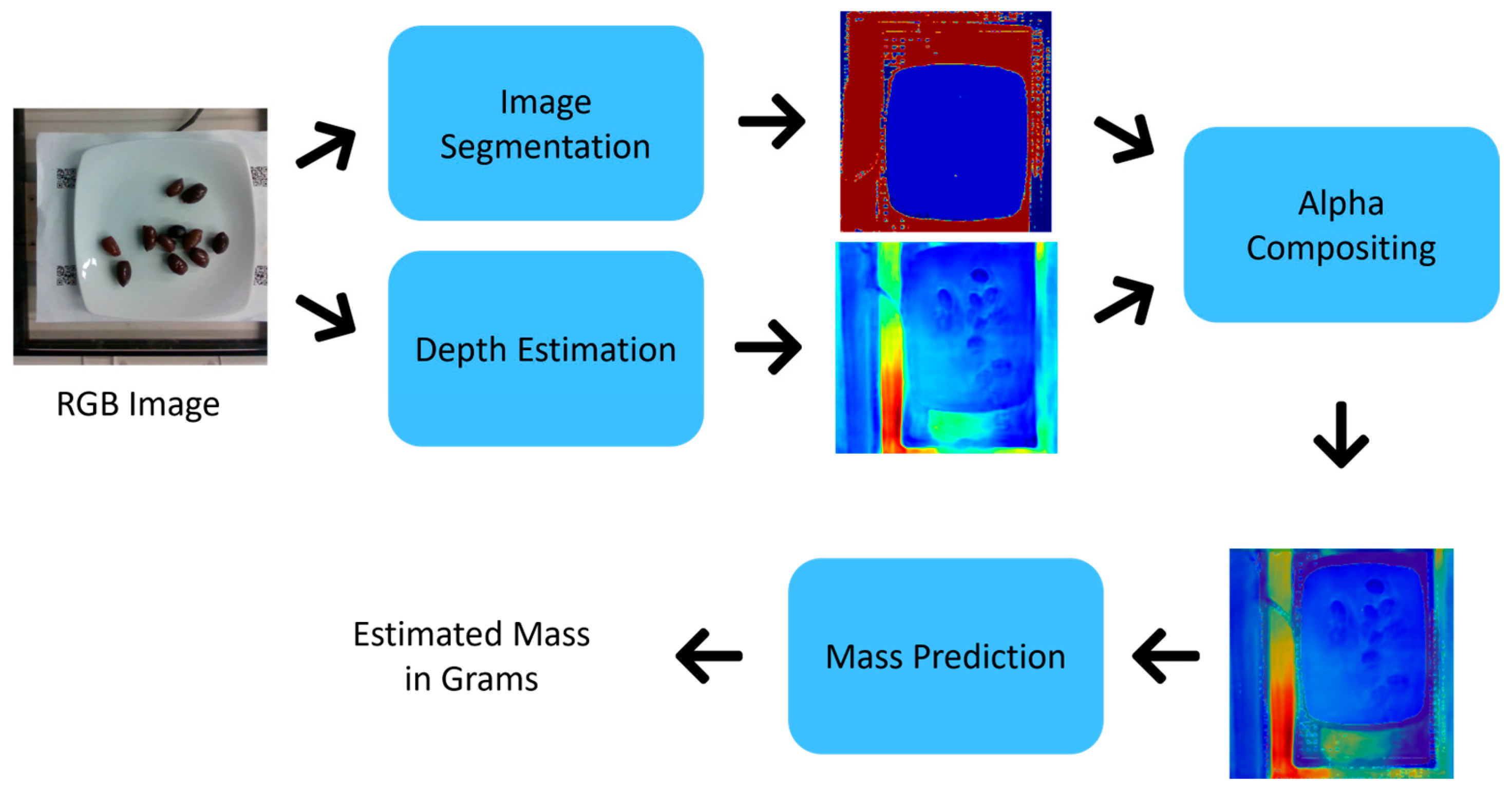

- We propose a three-stage, transformer-based approach for enhanced FME. The stages involve image segmentation to extract food regions, MDE to extract depth information, and FME to predict the food mass on plates.

- We use four variations of the SAM 2 model for image segmentation based on the SUECFood dataset. The GLPN model is employed for MDE using the Nutrition5k dataset, and the ViT model is utilized for FME.

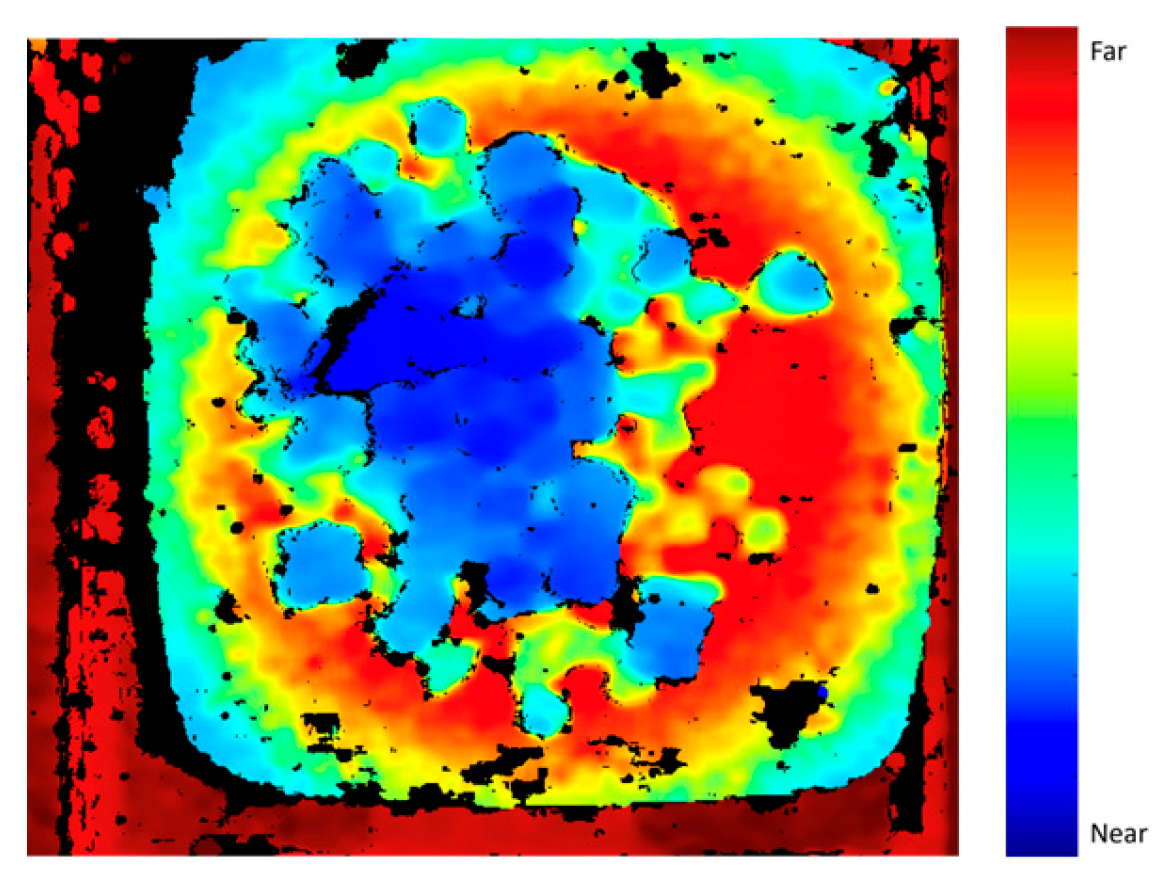

- We combine the image segmentation and MDE results using the AC method to ensure better contour definition in the depth images and, consequently, more accurate mass estimation namely, an MSE of 5.61 and an MAE of 1.07.

- We conduct a comparative study with prior research using the same dataset and demonstrate the superiority of our approach.

2. Literature Review

3. Proposed Approach

3.1. Dataset

- MuseFood: The MuseFood dataset [22] is a large-scale Japanese food image dataset designed primarily for food segmentation tasks. The key features of the MuseFood dataset are as follows:

- ∘

- RGB Images: The dataset contains 31,395 images of various food items, providing a substantial resource for food image segmentation.

- ∘

- Masks: Each image in the dataset is accompanied by a pixel-level annotation, or mask.

- Nutrition5k: The Nutrition5k dataset [15] is a large-scale, diverse dataset designed specifically for food image recognition, mass estimation, and calorie estimation tasks in the context of dietary assessment. The key features of the Nutrition5k dataset are as follows:

- ∘

- RGB Images: The dataset includes 5000 unique food dishes, offering substantial diversity in food types and portion sizes. Each dish is captured from multiple angles to enhance the accuracy of 3D reconstruction and volume estimation techniques.

- ∘

- Depth Images: A depth map is provided for each dish, captured using a depth camera to represent the distance of the food from the camera at each pixel.

- ∘

- Annotations: The dataset includes detailed annotations, such as dish ingredients (e.g., eggplant, roasted potatoes, cauliflower), to facilitate classification tasks. It also provides mass per ingredient, total dish mass, caloric information per ingredient, total calories, as well as fat, carbohydrate, and protein content for each dish and ingredient.

3.2. Image Segmentation

- Fine-Tuning: Each segmentation model variant (Hiera-B+, Hiera-L, Hiera-S, and Hiera-T) was fine-tuned to partition images into distinct regions such as food ingredients versus background. This training was performed using RGB images and their corresponding segmentation masks from the SUECFood dataset. A total of 80% of the dataset was allocated for training purposes. The models were trained for 1000 epochs with a fixed learning rate of 0.0001.

- Testing: The evaluation phase was conducted using the remaining 20% of the dataset. The results from this testing phase are summarized in Table 1.

- Inference: For inference, the best-performing checkpoint of each fine-tuned SAM 2 variant was applied to all RGB images in the Nutrition5k dataset. The goal of this inference step was to generate segmented versions of the images, ultimately facilitating mass estimation based on RGB inputs. This approach is critical because using the depth maps provided by the dataset directly would undermine the objective of the study, which emphasizes leveraging RGB images instead of depth camera data.

3.3. Monocular Depth Estimation

- Fine-tuning: The model was trained to generate depth maps using RGB images paired with ground-truth depth images from the Nutrition5k dataset. As with segmentation, 80% of the dataset was used for training. The model was trained over 10 epochs with a learning rate of 0.0001 and a batch size of 512.

- Testing: The model was evaluated using the remaining 20% of the dataset to assess its generalization performance.

- Inference: The best checkpoint obtained during fine-tuning was used to infer depth images for the entire Nutrition5k dataset, using RGB inputs.

3.4. Alpha Compositing

3.5. Food Mass Estimation

- Training: The model learns to estimate mass from the previously generated AC images. We train the model for 100 epochs, with a learning rate of 0.0001 and a batch size of 8 to avoid overloading the GPU. The data is split, with 80% used for training.

- Testing: Similarly to the previous stages, the model is evaluated on the remaining 20% of the dataset.

3.6. Experimental Settings

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Image Segmentation

4.2. Monocular Depth Estimation

4.3. Food Mass Estimation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Konstantakopoulos, F.S.; Georga, E.I.; Fotiadis, D.I. A Review of Image-Based Food Recognition and Volume Estimation Artificial Intelligence Systems. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 17, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhafzay, A.; Rouhafzay, G.; Jbilou, J. Image-Based Food Monitoring and Dietary Management for Patients Living with Diabetes: A Scoping Review of Calorie Counting Applications. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1501946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugas, K.R.; Giroux, M.-A.; Guerroudj, A.; Leger, J.; Rouhafzay, A.; Rouhafzay, G.; Jbilou, J. Calorie Counting Apps for Monitoring and Managing Calorie Intake in Adults with Weight-Related Chronic Diseases: A Decade-long Scoping Review (2013–2024). JMIR Prepr. 2024, 64139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehais, J.; Anthimopoulos, M.; Shevchik, S.; Mougiakakou, S. Two-View 3D Reconstruction for Food Volume Estimation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2016, 19, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannejad, H.; Matrella, G.; Ciampolini, P.; De Munari, I.; Mordonini, M.; Cagnoni, S. A New Approach to Image-Based Estimation of Food Volume. Algorithms 2017, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, F.P.-W.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, J.; Lo, B.P.L. Food Volume Estimation Based on Deep Learning View Synthesis from a Single Depth Map. Nutrients 2018, 10, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.-C.; Lim, Z.-Y.; Lin, H.-W. Food Intake Estimation Method Using Short-Range Depth Camera. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP), Beijing, China, 13–15 August 2016; pp. 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Xu, C.; Khanna, N.; Boushey, C.J.; Delp, E.J. Food Image Analysis: Segmentation, Identification and Weight Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), San Jose, CA, USA, 15–19 July 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, H.; Cao, S.; Xu, Q.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, H.; Jia, W.; Mao, Z.-H.; Sun, M. Human-Mimetic Estimation of Food Volume from a Single-View RGB Image Using an AI System. Electronics 2021, 10, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantakopoulos, F.; Georga, E.I.; Fotiadis, D.I. 3D Reconstruction and Volume Estimation of Food Using Stereo Vision Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 21st International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), Kragujevac, Serbia, 25–27 October 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Ren, Y.; Li, B.; Beatrice, B.; Que, J.; Cao, S.; Wu, Z.; Mao, Z.-H.; Lo, B.; Anderson, A.K.; et al. A Novel Approach to Dining Bowl Reconstruction for Image-Based Food Volume Estimation. Sensors 2022, 22, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, N.; Zainuddin, Z.; Tahir, Z. 3D Reconstruction with SFM-MVS Method for Food Volume Estimation. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2024, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Naritomi, S.; Yanai, K. Hungry Networks: 3D Mesh Reconstruction of a Dish and a Plate from a Single Dish Image for Estimating Food Volume. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia in Asia, Tokyo, Japan, 7–9 March 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, Y.; Ege, T.; Cho, J.; Yanai, K. DepthCalorieCam: A Mobile Application for Volume-Based Food-Calorie Estimation Using Depth Cameras. In Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Multimedia Assisted Dietary Management, Nice, France, 21 October 2019; pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Thames, Q.; Karpur, A.; Norris, W.; Xia, F.; Panait, L.; Weyand, T.; Sim, J. Nutrition5k: Towards Automatic Nutritional Understanding of Generic Food. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8903–8911. [Google Scholar]

- Pouladzadeh, P.; Shirmohammadi, S.; Al-Maghrabi, R. Measuring Calorie and Nutrition from Food Image. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2014, 63, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Yanai, K. An Automatic Calorie Estimation System of Food Images on a Smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Multimedia Assisted Dietary Management, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 16 October 2016; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Jia, W.; Bucher, T.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M. Image-Based Food Portion Size Estimation Using a Smartphone without a Fiducial Marker. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, F.P.-W.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, J.; Lo, B.P.L. Point2Volume: A Vision-Based Dietary Assessment Approach Using View Synthesis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 16, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wu, W.; Huang, Z. DPF-Nutrition: Food Nutrition Estimation via Depth Prediction and Fusion. Foods 2023, 12, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, W.; Hou, S.; Jia, W.; Zheng, Y. Rapid Non-Destructive Analysis of Food Nutrient Content Using Swin-Nutrition. Foods 2022, 11, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Tan, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W. MuseFood: Multi-Sensor-Based Food Volume Estimation on Smartphones. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation (SmartWorld/SCALCOM/UIC/ATC/CBDCom/IOP/SCI), Leicester, UK, 19–23 August 2019; pp. 899–906. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, N.; Gabeur, V.; Hu, Y.-T.; Hu, R.; Ryali, C.; Ma, T.; Khedr, H.; Rädle, R.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; et al. SAM 2: Segment Anything in Images and Videos. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.00714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Ka, W.; Ahn, P.; Joo, D.; Chun, S.; Kim, J. Global-Local Path Networks for Monocular Depth Estimation with Vertical CutDepth. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.07436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.; Nath, A. Scope and Issues in Alpha Compositing Technology. Int. Issues Alpha Compos. Technol. 2016, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An Image Is Worth 16×16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Nokhwal, S.; Chilakalapudi, P.; Donekal, P.; Nokhwal, S.; Pahune, S.; Chaudhary, A. Accelerating Neural Network Training: A Brief Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Metaheuristics & Swarm Intelligence, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 22–23 February 2024; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Eigen, D.; Puhrsch, C.; Fergus, R. Depth Map Prediction from a Single Image Using a Multi-Scale Deep Network. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 2, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar]

| Library | Version | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Torch | 2.4.1 | DL Framework |

| Torchvision | 0.19.1 | Image Processing |

| Transformers | 4.45.2 | Large Language Model Framework |

| SAM 2 | 1.11.2 | Image Segmentation |

| Pillow | 10.4.0 | Image Manipulation |

| Numpy | 1.26.4 | Numerical Computing |

| SAM 2 Variation | MSE | IoU (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hiera-T | 0.0149 | 94.35 |

| Hiera-S | 0.0162 | 94.94 |

| Hiera-B+ | 0.0196 | 94.97 |

| Hiera-L | 0.0086 | 95.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Besrour, S.; Rouhafzay, G.; Jbilou, J. A Three-Stage Transformer-Based Approach for Food Mass Estimation. Eng. Proc. 2025, 118, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26521

Besrour S, Rouhafzay G, Jbilou J. A Three-Stage Transformer-Based Approach for Food Mass Estimation. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 118(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26521

Chicago/Turabian StyleBesrour, Sinda, Ghazal Rouhafzay, and Jalila Jbilou. 2025. "A Three-Stage Transformer-Based Approach for Food Mass Estimation" Engineering Proceedings 118, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26521

APA StyleBesrour, S., Rouhafzay, G., & Jbilou, J. (2025). A Three-Stage Transformer-Based Approach for Food Mass Estimation. Engineering Proceedings, 118(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26521