Abstract

A novel highly sensitive voltammetric sensor based on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) modified with a mixture of cerium and tin dioxide nanoparticles (NPs) as a sensing layer was developed. Surfactants of various nature (anionic sodium dodecyl sulfate, cationic N-cetylpyridinium bromide, and non-ionic Triton X-100, Brij® 35, and Tween-80) were used as dispersive agents for NPs. Complete suppression and a significant decrease in the dye oxidation peak occurred in the case of Tween-80 and sodium dodecyl sulfate, respectively. CeO2–SnO2 NPs in Brij® 35 gave the best response to Acid Yellow 3 caused by its adsorption at the electrode surface. Linear dynamic ranges of 0.50–7.5 and 7.5–25 mg L−1 with a detection limit of 0.13 mg L−1 of Acid Yellow 3 were achieved using differential pulse mode in Britton–Robinson buffer pH 5.0.

1. Introduction

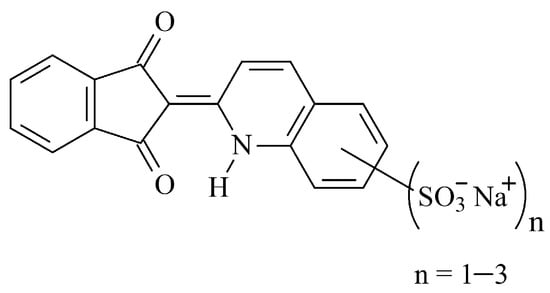

The synthetic dye Acid Yellow 3 (Quinoline Yellow S) is widely applied in the food and pharmaceutical industries to obtain the greenish yellow color of the final products. From a chemical point of view, the dye is a mixture of di-, mono-, and trisulfonates of 2-(2-quinolyl)indan-1,3-dione (Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1.

Acid Yellow 3 structure.

However, dye content is strictly regulated due to the dose-dependent toxic effects of living systems [2]. The maximum permitted level of Acid Yellow 3 in foodstuff is in the range of 10–300 mg kg−1 or mg L−1 depending on the type of product, while the acceptable daily intake is 0.5 mg/kg body weight/day [3]. Therefore, sensitive methods are required for Acid Yellow 3 determination, and electrochemical sensors are perspective ones. Nevertheless, quite limited examples of the electrochemical determination of this dye have been reported to date. All of them are focused on the application of modified electrodes due to the extremely low sensitivity of the dye response at the traditional carbon-based electrodes. Carbon nanomaterials, polymeric coverages (polyvinylpyrrolidone or polypyrrole), and various combinations of nanomaterials are used as electrode surface modifiers. Glassy carbon (GCE) and carbon paste (CPE) electrodes act as a platform for modifier immobilization. The analytical characteristics of Acid Yellow 3 are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Electrochemical sensors for Acid Yellow 3 determination.

All methods require a preconcentration step that increases the measurement time and can promote co-adsorption of other matrix components in real samples leading to worse selectivity of Acid Yellow 3 determination. The concentration of dye expressed in μM [5,6,7,8,9,10] is a significant methodological error as far as dye consists of the mixture of sulfonates and their exact ratio can vary.

Further enlargement of the electrode surface modifiers in Acid Yellow 3 electroanalysis is of interest. Transition metal oxide NPs (CeO2, Fe2O3, MnO2, SnO2, La2O3, MoO3, etc.) have been shown to be an effective sensing layer for various synthetic dyes [11,12,13,14]. A current trend in this type of electrochemical sensors is focused on the combination of several metal oxides in order to obtain a synergetic action of NPs [15,16,17]. Recently, mixed CeO2 and SnO2 NPs have shown a highly sensitive response to Sunset Yellow FCF [18]. Application of such a combination to another class of dyes, i.e., quinoline ones, can give an additional application area of mixed CeO2–SnO2 NPs in organic electroanalysis.

2. Materials and Methods

The stock solution with a concentration of 5060 mg L−1 was prepared from Acid Yellow 3 (TCI, Tokyo, Japan) by dissolution of the exact weight in distilled water.

Commercial CeO2 NPs (10% wt. water dispersion with particle size ˂ 25 nm (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)) and SnO2 NPs (powder with particle diameter < 100 nm (Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany)) were used for the preparation of an electrode surface modifier. The mixture of CeO2 and SnO2 NPs (1 mg mL−1) was obtained by sonication for 10 min in an ultrasonic bath (WiseClean WUC-A03H from DAIHAN Scientific Co., Ltd., Wonju-si, Republic of Korea). An amount of 0.10–1.0 mM surfactant solutions were used as dispersive medium for NPs. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Ph. Eur. Grade, Panreac (Barcelona, Spain), Brij® 35 (98%, Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium)), Tween® 80 (Merck, Steinheim, Germany), Triton X-100 and 98% N-cetylpyridinium bromide (N-CPB) from Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany) were used. Their 1.0 mM (2.5 mM for Brij® 35) stock solutions were prepared in distilled water. The electrode surface was modified by drop casting of 3 μL of NP dispersion. Other chemicals were of c.p. grade and used as received.

The potentiostat/galvanostat PGSTAT 302N with FRA 32M module (Metrohm B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands) with NOVA 1.10.1.9 software was used for electrochemical measurements. GCE (⌀ = 3 mm) from CH Instruments, Inc. (Bee Cave, TX, USA) or GCE modified with CeO2–SnO2 NPs, reference Ag/AgCl (3M NaCl) electrode (Metrohm B.V., Herisau, Switzerland), and auxiliary electrode (platinum wire) from Econix-Expert Ltd. (Moscow, Russia) were used. All measurements were performed in a glass electrochemical cell containing Britton–Robinson buffer (BRB). Cyclic (CVs) or differential pulse (DPVs) voltammograms were recorded from 0.0 to 1.5 V or 0.0 to 1.4 V, respectively.

A high-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope MerlinTM (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used at a 5 kV accelerating voltage and a 300 pA emission current.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Voltammetric Characteristics of Acid Yellow 3

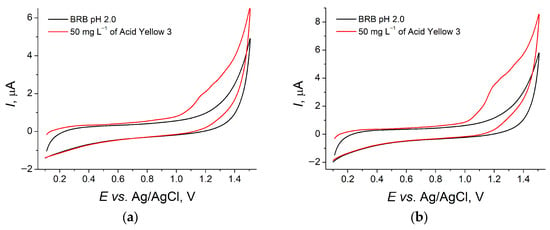

Acid Yellow 3 is irreversibly oxidized at +1.17 V on the bare GCE in BRB pH 2.0 (Figure 2). The oxidation signal is poorly expressed in spite of the high concentration of the dye and cannot be used for analytical purposes.

Figure 2.

CVs of 50 mg L−1 Acid Yellow 3 at bare GCE (a) and GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35 (0.5 mM) (b) in BRB pH 2.0, υ = 0.10 V s−1.

The effect of electrode surface modification with a mixture of CeO2–SnO2 NPs dispersed in 0.10 mM surfactant medium (anionic SDS, cationic N-CPB, and non-ionic Triton X-100, Brij® 35, and Tween-80) on the Acid Yellow 3 response was evaluated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Voltammetric parameters of Acid Yellow 3 at bare GCE and GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–surfactant. csurfactant = 0.10 mM, n = 5; p = 0.95.

Complete suppression and a significant decrease in the dye oxidation peak occur in the case of Tween-80 and sodium dodecyl sulfate, respectively. The presence of Tween-80 blocks the electron transfer that is seen even for the supporting electrolyte. The electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged SDS and dye can explain a 2-fold decrease in the oxidation peak currents as well as an anodic shift in the oxidation potential. Other surfactants provide an improvement of the Acid Yellow 3 signal which is more pronounced in the case of non-ionic surfactants. Electrostatic interactions take place in the case of cationic N-CPB that agree well with the data reported earlier [18,19]. The CeO2–SnO2 NPs in Brij® 35 give the best response (7-fold increase in the oxidation peak currents vs. bare GCE) due to the dye adsorption at the electrode surface via hydrophobic interactions.

The effect of Brij® 35 concentration (0.05–1.0 mM) in NP dispersion on the oxidation peak parameters of Acid Yellow 3 has been tested. The dye oxidation currents are increased, and oxidation potential remains unchanged when 0.05–0.5 mM of Brij® 35 is used. Further increase in surfactant concentration to 1.0 mM leads to significant downfall in oxidation peak currents that is probably caused by the formation of Brij® 35 micelles and their more complex aggregates, such as cylindrical ones [20], which affect electrode reaction kinetics. The highest oxidation currents (0.48 ± 0.03 μA at +1.20 V) are obtained for 0.5 mM Brij® 35. Thus, GCE modified with CeO2–SnO2 NPs dispersed in 0.5 mM Brij® 35 has been chosen for further investigations.

3.2. Electrode Characterization

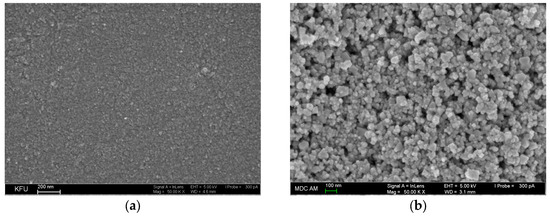

The scanning electron microscopic characterization of the electrode surface morphology is shown in Figure 3. GCE has a relatively smooth unstructured surface of a low roughness (Figure 3a). CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35 are evenly distributed at the electrode surface and presented by spherical and single rhomboid structures of 28–90 nm (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopic images of the electrode surface: (a) bare GCE; (b) GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35.

The electrochemical parameters of the electrodes have been studied with chronoamperometry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) (Table 3). The electroactive surface area (A, cm2) of GCE and GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35 has been evaluated using chronoamperometry of 1.0 mM ferrocyanide ions in 0.1 M KCl. Electrolysis has been carried out at 0.60 V for 25 s and the Cottrell equation has been applied for the calculations [21]. EIS has been performed in the presence of 1.0 mM ferro/ferricyanide ions as the redox probe in 0.1 M KCl at 0.25 V (half-sum of the probe redox peaks) and the impedance spectra have been fitted using a Randles equivalent circuit [22]. The heterogeneous electron transfer rate constants (ket) (Table 3) have been calculated using electrochemical impedance data as described in [23]. An 8.5-fold decrease in the electron transfer resistance (Ret) for the modified electrode clearly indicates the increase in the electron transfer rate that agrees well with the ket values.

Table 3.

Electrochemical parameters of the electrodes (n = 5; p = 0.95).

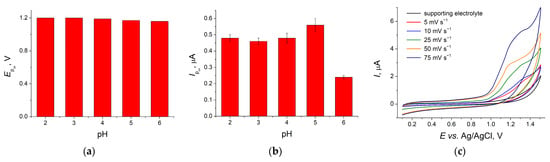

3.3. Acid Yellow 3 Electrooxidation Parameters

Changes in the Acid Yellow 3 oxidation peak at various pH of supporting electrolyte and potential scan rates have been used to elucidate electrode reaction parameters. Well-defined oxidation peak of dye is observed in the pH range of 2.0–6.0. The dye signal disappears completely at pH 7.0. The oxidation potential is almost unchanged with increase in pH (Figure 4a) indicating a proton-independent electrooxidation process. The Acid Yellow 3 oxidation peak currents are increased with pH growth achieving a maximum at pH 5.0 (Figure 4b). Then, a 2.3-fold decrease in currents occurs at pH 6.0. Thus, BRB pH 5.0 has been used in further studies.

Figure 4.

Changes in the oxidation peak of Acid Yellow 3 at various pH and potential scan rates on the GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35: (a) oxidation peak potential of 100 mg L−1 dye, υ = 0.10 V s−1; (b) oxidation peak currents of 100 mg L−1 dye, υ = 0.10 V s−1; (c) CVs of 250 mg L−1 dye in BRB pH 5.0 at υ = 0.005–0.075 V s−1.

The effect of the potential scan rate in the range of 5–150 mV s−1 on the dye oxidation peak parameters has been studied (Figure 4c). The peak currents achieve maximum at a scan rate of 75 mV s−1. Further increase in potential scan rate does not give any changes in the oxidation peak currents. Thus, a surface-controlled electrooxidation of Acid Yellow 3 is suggested and confirmed by the linear plot of Ip vs. potential scan rate (Equation (1)) and the slope of 1.01 for the plot lnIp vs. ln υ (Equation (2)).

Ip[μA] = (−0.02 ± 0.02) + (0.0148 ± 0.0005)υ [mV s−1] R2 = 0.9963,

lnI [µA] = (2.7 ± 0.2) + (1.01 ± 0.04)lnυ [V s−1] R2 = 0.9943.

These results agree well with the data obtained for other modifier electrodes [4,5,6,7,8].

Acid Yellow 3 electrooxidation at the GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35 proceeds irreversibly as long as there are no reduction steps on the CVs. The anodic transfer coefficient is equal to 0.5 in this case. Thus, according to ∆E1/2 = 62.5/αan, two electrons participate in Acid Yellow 3 oxidation. Similar data have been reported for CPE–polyvinylpyrrolidone [7] and GCE/ERGO–MnO2 nanorods [9].

3.4. Acid Yellow 3 Quantification

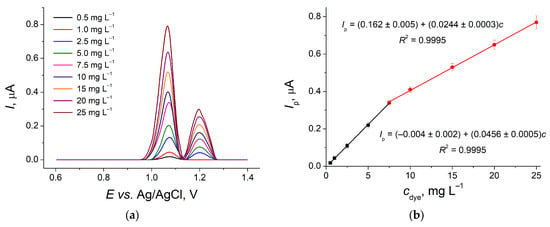

DPV has been applied for the dye quantification. The preliminary optimization of the pulse parameters has shown that the best response is obtained at a modulation amplitude of 0.10 V and a modulation time of 0.025 s. Acid Yellow 3 shows well-defined oxidation peaks at +1.07 and +1.20 V (Figure 5a). The second peak appears at higher concentrations only. Two linear dynamic ranges of 0.50–7.5 and 7.5–25 mg L−1 (Figure 5b) with a detection limit of 0.13 mg L−1 of Acid Yellow 3 have been achieved using the first oxidation peak. The sensor demonstrates sufficient sensitivity to dye as slopes of the calibration plots shown.

Figure 5.

(a) Baseline-corrected DPVs of Acid Yellow 3 at GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35 in BRB pH 5.0. ΔEpulse = 0.10 V, tpulse = 0.025 s, υ = 0.010 V s−1. (b) Calibration plot of Acid Yellow 3.

The high accuracy of the sensor developed is confirmed on the dye model solutions and confirmed by recovery values (Table 4). The RSD of 0.007–0.04 indicates the absence of random errors in Acid Yellow 3 determination.

Table 4.

Acid Yellow 3 determination in model solutions on GCE/CeO2–SnO2 NPs–Brij® 35 in BRB pH 5.0 (n = 5; p = 0.95).

3.5. Real Sample Analysis

The method developed has been tested on real samples, i.e., beverages and food colorants E104 available in local stores. The results obtained have been compared to independent spectrophotometric determination [24] (Table 5). The data of the two methods agree well. The F-test confirms a similar precision of the two methods while t-test indicates the absence of statistically significant errors of determination. Moreover, Acid Yellow 3 contents in food colorants are in line with the labeled percentage of dye.

Table 5.

Acid Yellow 3 contents in real samples (n = 5; p = 0.95).

4. Conclusions

Mixed CeO2–SnO2 NPs dispersed in non-ionic Brij® 35 have been shown to be a sufficiently sensitive layer of voltammetric sensor to Acid Yellow 3 dye. The sensor is simple, inexpensive, and express in fabrication, provides fast response to the target dye, and does not need a preconcentration step. The presence of Brij® 35 enables a hydrophobic interaction with the dye and its adsorption at the electrode surface. The data obtained confirm the effectivity of the metal oxide NPs as the electrode surface modifier and extend their application area in organic analysis.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Author would like to acknowledge Aleksei Rogov (Laboratory of Scanning Electron Microscopy, Interdisciplinary Center for Analytical Microscopy, Kazan Federal University) for the SEM measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Damant, A.P. Food colourants. In Handbook of Textile and Industrial Dyeing; Clark, M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 252–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amchova, P.; Kotolova, H.; Ruda-Kucerova, J. Health safety issues of synthetic food colorants. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 73, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA, 2015. Refined exposure assessment for Quinoline Yellow (E 104). EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y. Electrochemical sensor for hazardous food colourant quinoline yellow based on carbon nanotube-modified electrode. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Fu, L.; Wang, A.; Cai, W. Electrochemical detection of quinoline yellow in soft drinks based on layer-by-layer fabricated multi-walled carbon nanotube. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 3530–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, A.; Cai, W.; Lin, H. Sensitive determination of quinoline yellow using poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) functionalized reduced graphene oxide modified grassy carbon electrode. Food Chem. 2015, 181, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, Z.; Wang, J. Sensitive and rapid determination of quinoline yellow in drinks using polyvinylpyrrolidone-modified electrode. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, X.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, J. Rapid detection of quinoline yellow in soft drinks using polypyrrole/single-walled carbon nanotubes composites modified glass carbon electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2014, 725, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Deng, P.; Tian, Y.; Magesa, F.; Jiu, J.; Li, G.; He, Q. Construction of effective electrochemical sensor for the determination of quinoline yellow based on different morphologies of manganese dioxide functionalized graphene. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 84, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Hristova, L.; Martínez-Moro, R.; Vázquez, L.; Ellis, G.J.; Sánchez, L.; del Pozo, M.; Petit-Domínguez, M.D.; Casero, E.; Quintana, C. A 2D tungsten disulphide/diamond nanoparticles hybrid for an electrochemical sensor development towards the simultaneous determination of sunset yellow and quinoline yellow. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 324, 128731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimadutdinova, L.; Ziyatdinova, G.; Davletshin, R. Selective voltammetric sensor for the simultaneous quantification of Tartrazine and Brilliant Blue FCF. Sensors 2023, 23, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyatdinova, G.K.; Budnikov, H.C. Voltammetric determination of tartrazine on an electrode modified with cerium dioxide nanoparticles and cetyltriphenylphosphonium bromide. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 77, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.Z.; Baghelani, Y.-M.; Mousazadeh, F.; Rahimi, S.; Mohammad-Hassani, M. Electrochemical determination of amaranth in food samples by using modified electrode. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2022, 12, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyatdinova, G.; Gimadutdinova, L.; Bychikhina, D. Voltammetric sensors based on the mixed metal oxide nanoparticles for food dye determination. Eng. Proc. 2024, 82, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Varela, A.; Cardenas-Riojas, A.A.; Nagles, E.; Hurtado, J. Detection of allura red in food samples using carbon paste modified with lanthanum and titanium oxides. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202204737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, K.; Chakroborty, S.; Doshi, P.; Chandra, P.; Ramakrishna, D.S.; Bal, T.; Darwish, I.A.; Mantry, S.P.; Soren, S.; Barik, A.; et al. Investigating CuO-ZrO2 Mixed metal oxide nanocomposites for electrochemical sensing of food colors. Luminescence 2024, 39, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Riojas, A.A.; Calderon-Zavaleta, S.L.; Quiroz-Aguinaga, U.; Muedas-Taipe, G.; Carhuayal-Alvarez, S.M.; Ascencio-Flores, Y.F.; Ponce-Vargas, M.; Baena-Moncada, A.M. Modified electrochemical sensors for the detection of selected food azo dyes: A review. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202300490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimadutdinova, L.; Ziyatdinova, G.; Davletshin, R. Voltammetric sensor based on the combination of tin and cerium dioxide nanoparticles with surfactants for quantification of Sunset Yellow FCF. Sensors 2024, 24, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziyatdinova, G.; Yakupova, E.; Davletshin, R. Voltammetric determination of hesperidin on the electrode modified with SnO2 nanoparticles and surfactants. Electroanalysis 2021, 33, 2417–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Madarász, Á. Structure of BRIJ-35 nonionic surfactant in water: A reverse Monte Carlo study. Langmuir 2006, 22, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A.J.; Faulkner, L.R. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2001; 864p. [Google Scholar]

- Lasia, A. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Its Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; 367p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randviir, E.P. A cross examination of electron transfer rate constants for carbon screen-printed electrodes using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and cyclic voltammetry. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 286, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgür, M.Ü.; Koyuncu, İ. The simultaneous determination of Quinoline Yellow (E-104) and Sunset Yellow (E-110) in syrups and tablets by second derivative spectrophotometry. Turk. J. Chem. 2002, 26, 501–508. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).