Design and Implementation of a Wi-Fi-Enabled BMS for Real-Time LiFePO4 Cell Monitoring †

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LiCoO2) or LCO;

- Lithium Manganese Oxide (LiMn2O4) or LMO;

- Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide (LiNiCoAlO2)—NCA;

- Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (LiNiMnCoO2)—NMC;

- Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4)—LFP.

- Long service life with over 3000 to 5000 life cycles available;

- Extreme safety, with a high thermal runaway threshold and superior durability;

- Tolerance to full-charge conditions.

- State of Charge (SoC), which describes the cells charge as a %;

- State of Health (SoH), which describes the battery maximum charge compared to nominal as the battery life indicator;

- State of Power, which describes the maximum power the battery can provide;

- Depth of Discharge (DoD), which describes the capacity utilized at a certain use, e.g., from 100% to 40% discharging.

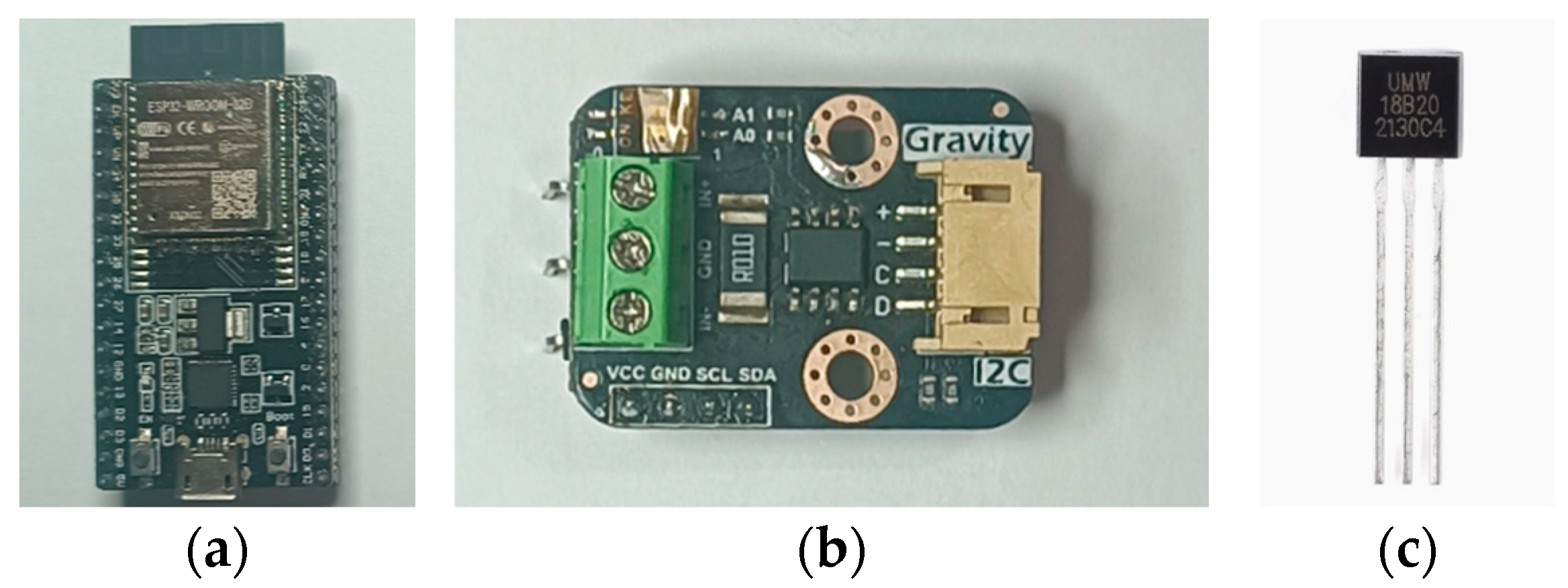

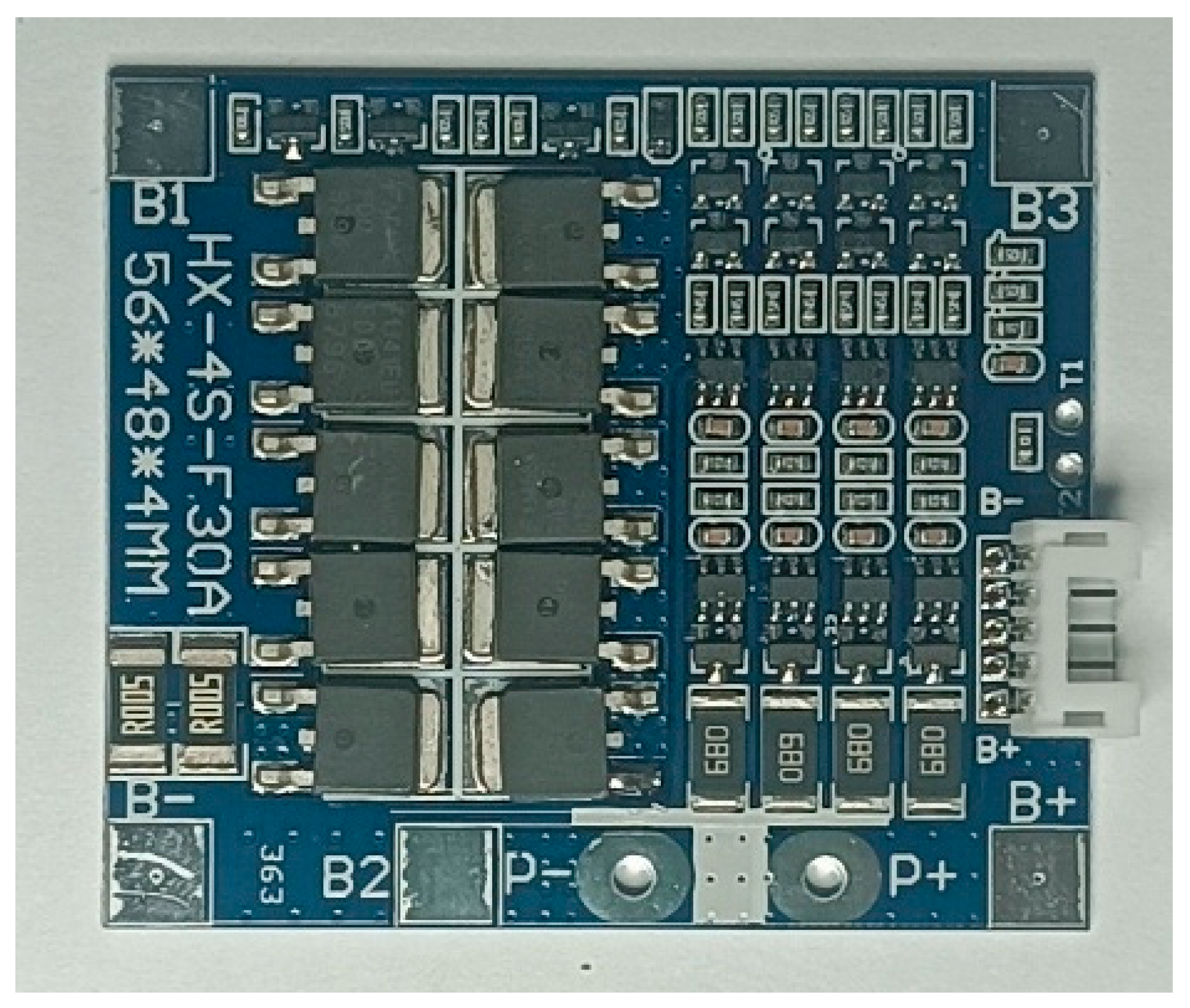

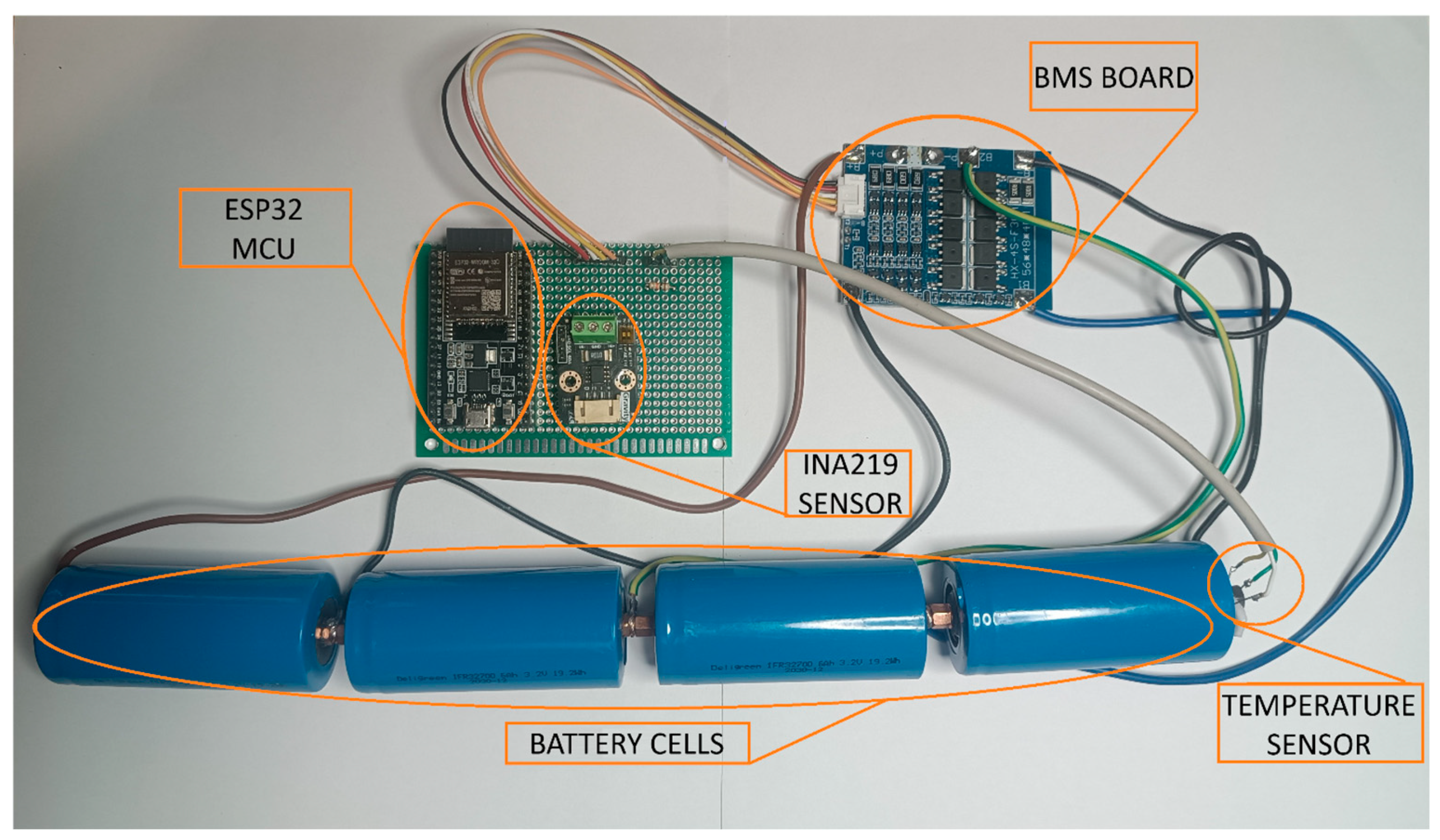

2. Materials and Methods

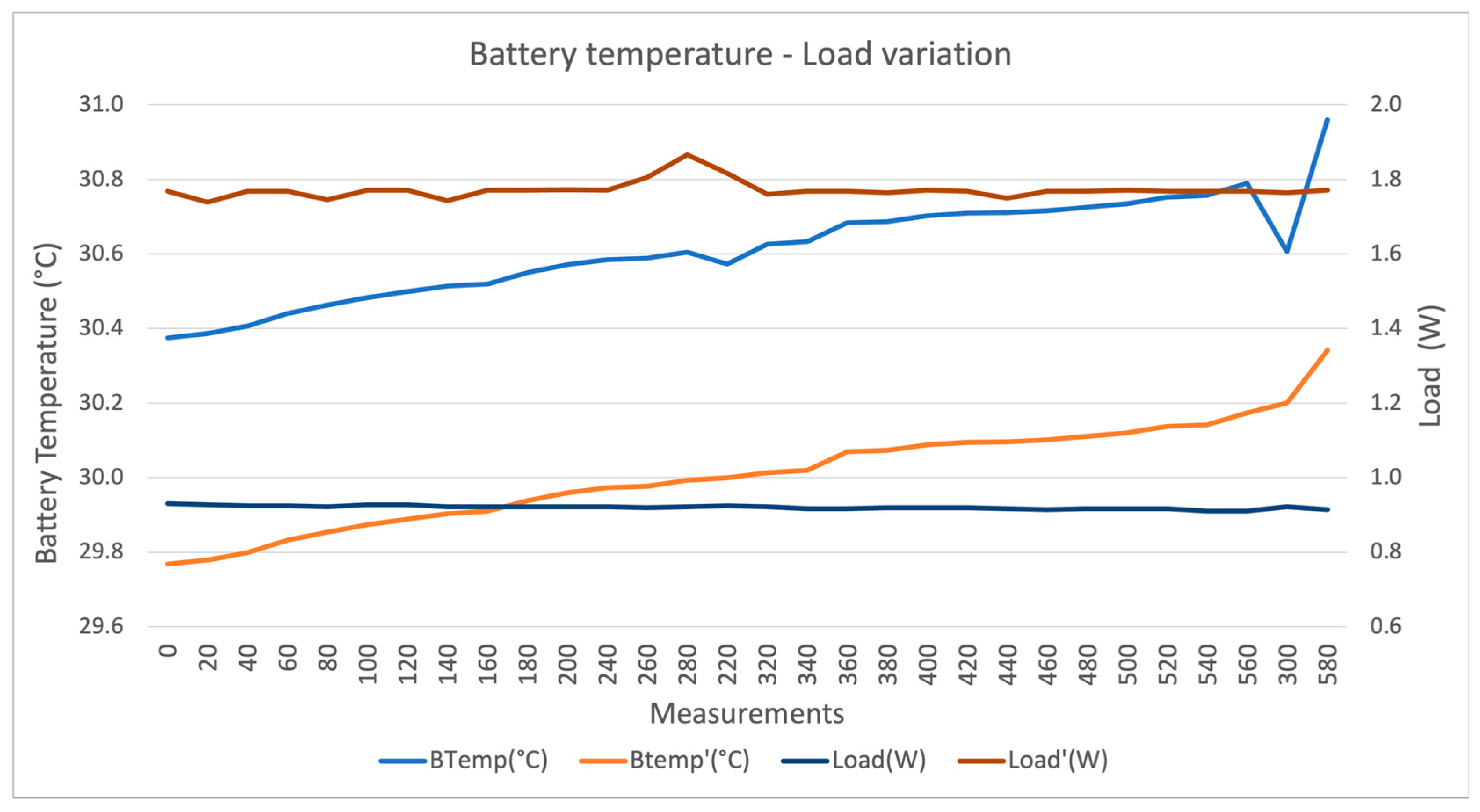

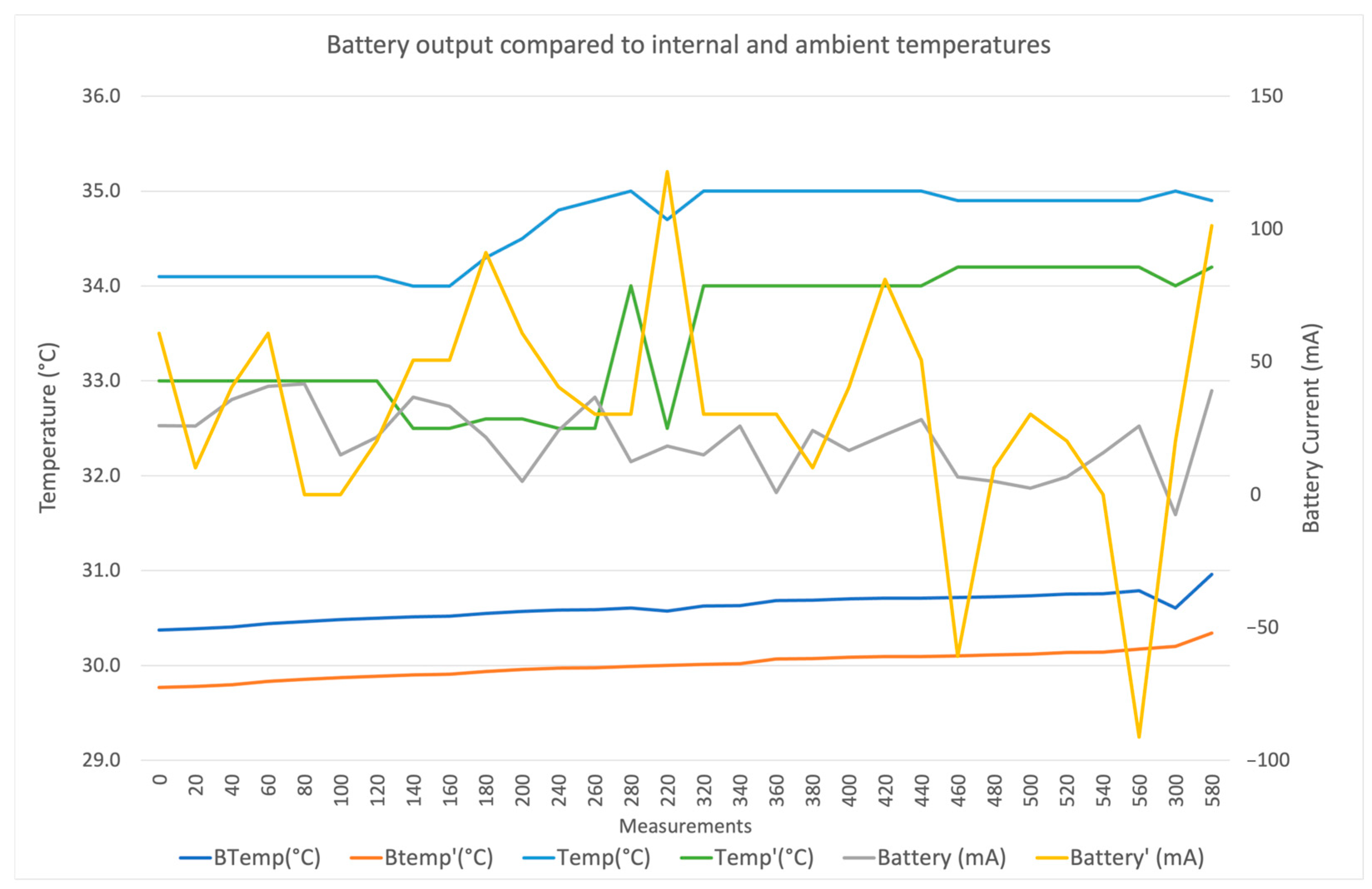

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, H.; Aifantis, K.E. Applications of Lithium Batteries. In Rechargeable Ion Batteries; Kumar, R., Aifantis, K., Hu, P., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 83–103. ISBN 9783527350186. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnieri, M. Secondary Batteries for Mobile Applications: From Lead to Lithium [Historical]. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2022, 16, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comanescu, C. Ensuring Safety and Reliability: An Overview of Lithium-Ion Battery Service Assessment. Batteries 2025, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.-W.; Lan, T.; Yin, H.; Liu, Y. Development and Commercial Application of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles: A Review. Processes 2025, 13, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamathulla, S.; Dhanamjayulu, C. A Review of Battery Energy Storage Systems and Advanced Battery Management System for Different Applications: Challenges and Recommendations. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera, J.; Arribas, J.R.; De Castro, R.M.; Núñez, C.S. Semi-Empirical Ageing Model for LFP and NMC Li-Ion Battery Chemistries. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahallawy, M.; Elfouly, T.; Alouani, A.; Massoud, A.M. A Comprehensive Review of Lithium-Ion Batteries Modeling, and State of Health and Remaining Useful Lifetime Prediction. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 119040–119070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoy, K.R.; Lukong, V.T.; Yoro, K.O.; Makambo, J.B.; Chukwuati, N.C.; Ibegbulam, C.; Eterigho-Ikelegbe, O.; Ukoba, K.; Jen, T.-C. Lithium-Ion Batteries and the Future of Sustainable Energy: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 223, 115971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menye, J.S.; Camara, M.-B.; Dakyo, B. Lithium Battery Degradation and Failure Mechanisms: A State-of-the-Art Review. Energies 2025, 18, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xia, X.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, X.; Ouyang, T.; Feng, H. A Balanced SOH-SOC Control Strategy for Multiple Battery Energy Storage Units Based on Battery Lifetime Change Laws. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 7725–7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimpas, D.; Kaminaris, S.D.; Aldarraji, I.; Piromalis, D.; Vokas, G.; Papageorgas, P.G.; Tsaramirsis, G. Energy Management and Storage Systems on Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 61, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Priyadarshi, N.; Twala, B. Digital Technology Implementation in Battery-Management Systems for Sustainable Energy Storage: Review, Challenges, and Recommendations. Electronics 2022, 11, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimpas, D.; Orfanos, V.A.; Chalkiadakis, P.; Christakis, I. Design and Development of a Low-Cost and Compact Real-Time Monitoring Tool for Battery Life Calculation. Eng. Proc. 2023, 58, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Deligreen IFR-32700 LFP Battery Datasheet. Available online: https://evparts.ir/uploadfile/file_portal/site_4540_web/file_portal_end/IFR32700N60-SPEC_FB0819-R01-IFR32700N60(1).pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- ESP32-WROOM-32 Datasheet. Available online: https://www.espressif.com/sites/default/files/documentation/esp32-wroom-32_datasheet_en.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- INA219 I2C—Digital Wattmeter SKU: SEN0291 Datasheet. Available online: https://wiki.dfrobot.com/Gravity:%20I2C%20Digital%20Wattmeter%20SKU:%20SEN0291 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- DS18B20 Programmable Resolution 1-Wire Digital Thermometer Datasheet. Available online: https://cdn.sparkfun.com/datasheets/Sensors/Temp/DS18B20.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- BMS-40A-4S-E Datasheet. Available online: https://www.mantech.co.za/datasheets/products/BMS-40A-4S_SGT.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Kychkin, A.; Deryabin, A.; Vikentyeva, O.; Shestakova, L. Architecture of Compressor Equipment Monitoring and Control Cyber-Physical System Based on Influxdata Platform. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing (ICIEAM), Sochi, Russia, 25–29 March 2019; IEEE: Sochi, Russia, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Grafana Labs—The Open Platform for Analytics and Monitoring. Available online: https://grafana.com/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- SKYRC MC500 Datasheet. Available online: https://manuals.plus/skyrc/mc5000-cylindrical-battery-charger-and-analyzer-manual (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Zhou, R.; Lu, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, K. Research on Lithium Iron Phosphate Battery Balancing Strategy for High-Power Energy Storage System. Energies 2025, 18, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Previous Work [13] | This Work |

|---|---|---|

| SoC Range | 60–100% | 40–100% |

| SoH at end | 100% | 100% |

| SoP | 14.8 A | 20 A 1 |

| DoD | 40% | 40–60% |

| Maximum Current (mA) | 40 mA | 110 mA |

| Temperature Range | 30.3 to 31 °C | 29.8 to 30.3 °C |

| Faster Cooling | X | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Christakis, I.; Orfanos, V.A.; Christoforidis, C.; Rimpas, D. Design and Implementation of a Wi-Fi-Enabled BMS for Real-Time LiFePO4 Cell Monitoring. Eng. Proc. 2025, 118, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26613

Christakis I, Orfanos VA, Christoforidis C, Rimpas D. Design and Implementation of a Wi-Fi-Enabled BMS for Real-Time LiFePO4 Cell Monitoring. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 118(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26613

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristakis, Ioannis, Vasilios A. Orfanos, Chariton Christoforidis, and Dimitrios Rimpas. 2025. "Design and Implementation of a Wi-Fi-Enabled BMS for Real-Time LiFePO4 Cell Monitoring" Engineering Proceedings 118, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26613

APA StyleChristakis, I., Orfanos, V. A., Christoforidis, C., & Rimpas, D. (2025). Design and Implementation of a Wi-Fi-Enabled BMS for Real-Time LiFePO4 Cell Monitoring. Engineering Proceedings, 118(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECSA-12-26613