Predictive Modeling of Polyphenol Concentration After Sequencing Batch Reactor Winery Wastewater Treatment †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.3. Data Collection

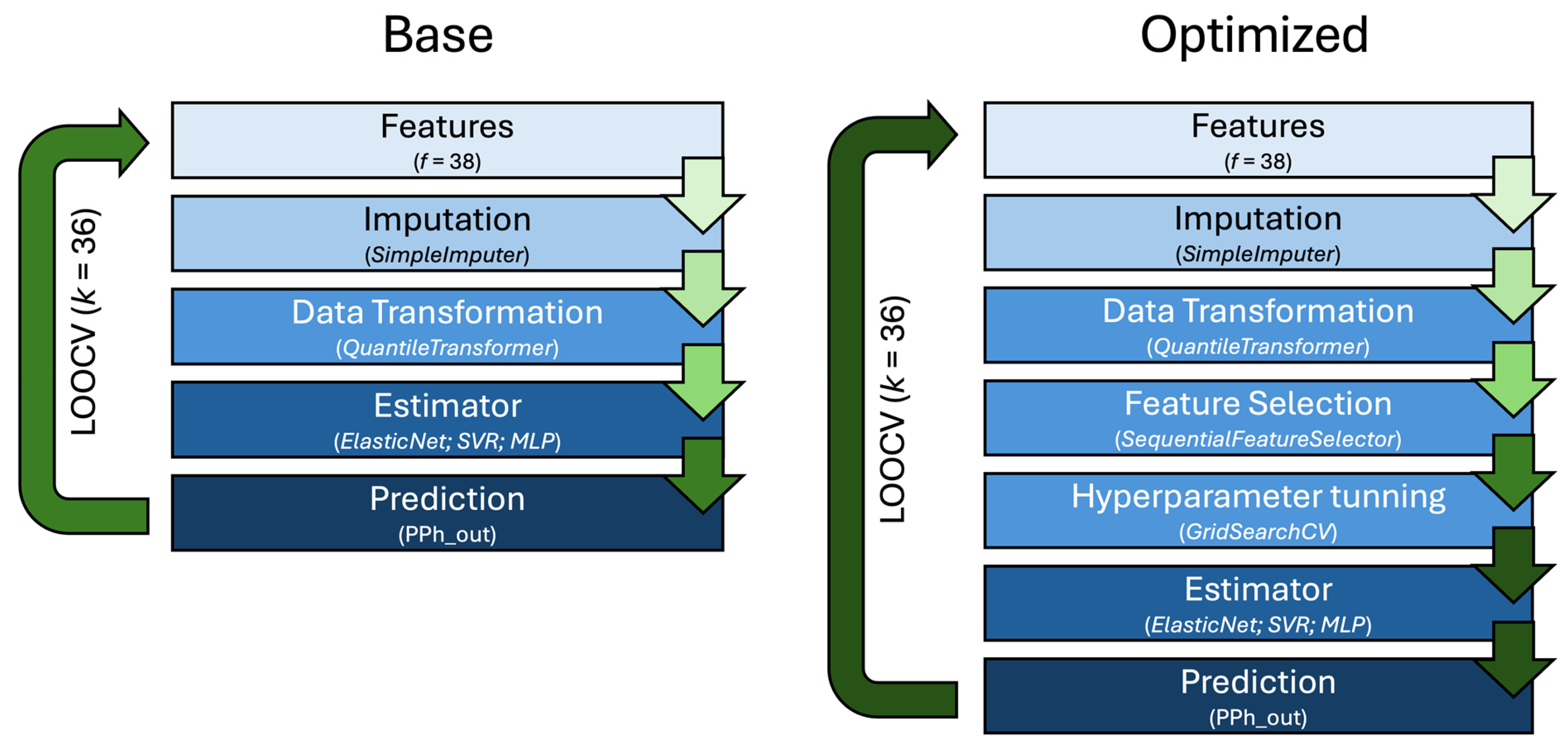

2.4. Machine Learning Model Selection and Optimization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reactor Performance

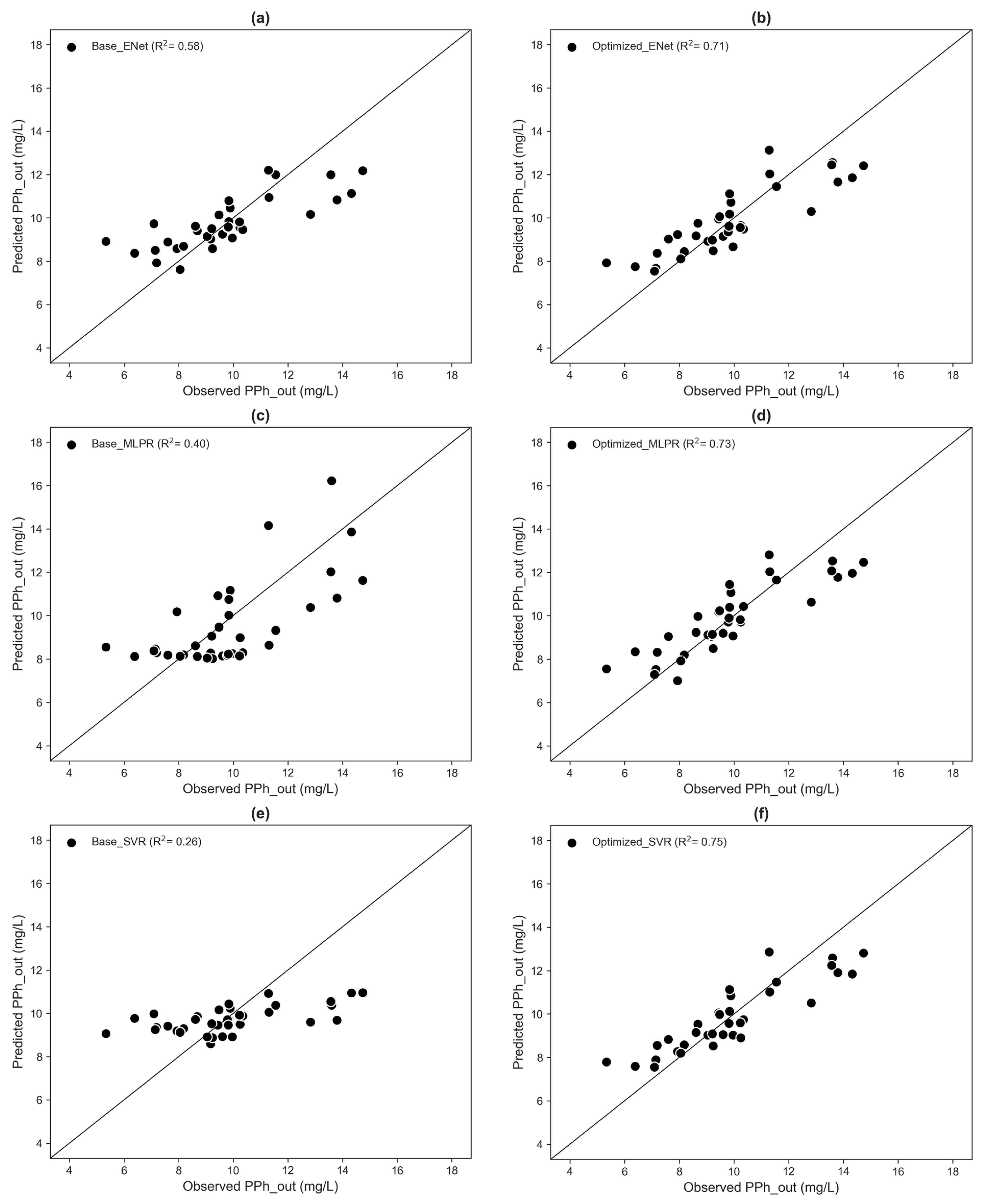

3.2. Model Development and Prediction

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CoV | Coefficient of Variation |

| DIC | Dissolved Inorganic Carbon |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| ENet | ElasticNet |

| FSS | Fixed Suspended Solids |

| HRT | Hydraulic Retention Time |

| LOOCV | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLPR | Multi-Layer Perceptron Regressor |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| SBR | Sequencing Batch Reactor |

| SRT | Sludge Retention Time |

| SVR | Support Vector Regressor |

| TDC | Total Dissolved Carbon |

| TDN | Total Dissolved Nitrogen |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| VSS | Volatile Suspended Solids |

| VER | Volume Exchange Ratio |

References

- Latessa, S.H.; Hanley, L.; Tao, W. Characteristics and Practical Treatment Technologies of Winery Wastewater: A Review for Wastewater Management at Small Wineries. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Pirra, A.; Jorge, N.; Peres, J.A.; Lucas, M.S. Enhancing Sustainability in Wine Production: Evaluating Winery Wastewater Treatment Using Sequencing Batch Reactors. In Proceedings of the 4th International Electronic Conference on Applied Sciences, Online, 27 October–10 November 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 56, p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Baía, A.; Lopes, A.; Nunes, M.J.; Ciríaco, L.; Pacheco, M.J.; Fernandes, A. Removal of Recalcitrant Compounds from Winery Wastewater by Electrochemical Oxidation. Water 2022, 14, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menashe, O.A.; Orlofsky, E.; Bankowski, P.; Kurzbaum, E. Winery Wastewater Innovative Biotreatment Using an Immobilized Biomass Reactor Followed by a Sequence Batch Reactor: A Case Study in Australia. Processes 2025, 13, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Bhushan, B.; Rodriguez-Turienzo, L. Recovery of Polyphenols onto Porous Carbons Developed from Exhausted Grape Pomace: A Sustainable Approach for the Treatment of Wine Wastewaters. Water Res. 2018, 145, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen Ramos, L.; Pluschke, J.; Bernardes, A.M.; Geißen, S.-U. Polyphenols in Food Processing Wastewaters: A Review on Their Identification and Recovery. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2023, 5, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, C.; Marchão, L.; Lucas, M.S.; Peres, J.A. Application of Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Treatment of Recalcitrant Agro-Industrial Wastewater: A Review. Water 2019, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, F.-S.; Carbureanu, M.; Mihalache, S.F. Application of Machine Learning Models in Optimizing Wastewater Treatment Processes: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Thunéll, S.; Lindberg, U.; Jiang, L.; Trygg, J.; Tysklind, M.; Souihi, N. A Machine Learning Framework to Improve Effluent Quality Control in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Z.; Liu, X.; Igou, T.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y. Using Hybrid Machine Learning to Predict Wastewater Effluent Quality and Ensure Treatment Plant Stability. Water 2025, 17, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanrolleghem, P.A.; Khalil, M.; Serrao, M.; Sparks, J.; Therrien, J.-D. Machine Learning in Wastewater: Opportunities and Challenges—“Not Everything Is a Nail!”. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2025, 93, 103271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzooei, S.; Amerlinck, Y.; Abolfathi, S.; Panepinto, D.; Nopens, I.; Lorenzi, E.; Meucci, L.; Zanetti, M.C. Data Scarcity in Modelling and Simulation of a Large-Scale WWTP: Stop Sign or a Challenge. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 28, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janga, K.; Begum, S.; Anupoju, G.R. Effect of Residence Time and Temperature on Pyrolysis of Water Hyacinth Leaf Biomass (WHLB): Experiments and Modelling through ML and Validation by Leave One Out Cross Validation (LOOCV). Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 32, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-T.; Chang, Y.-H.; Shiau, S.-Y. Rheological, Antioxidative and Sensory Properties of Dough and Mantou (Steamed Bread) Enriched with Lemon Fiber. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 61, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water & Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0875530475. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshvaght, H.; Permala, R.R.; Razmjou, A.; Khiadani, M. Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Machine Learning Algorithms in Predicting Raw Wastewater Characteristics: An Analysis Based on Weekly Field Data. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 78, 108702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, L.A.; Puma, G.L.; Fatta-Kassinos, D. Treatment of Winery Wastewater by Physicochemical, Biological and Advanced Processes: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 286, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benitez, F.J.; Beltran-Heredia, J.; Peres, J.A.; Dominguez, J.R. Kinetics of P-Hydroxybenzoic Acid Photodecomposition and Ozonation in a Batch Reactor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 73, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, M.S.; Mouta, M.; Pirra, A.; Peres, J.A. Winery Wastewater Treatment by a Combined Process: Long Term Aerated Storage and Fenton’s Reagent. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Units | Influent | Reactor | Effluent |

| Temperature | °C | T_in | T_sbr | T_out |

| pH | - | pH_in | pH_sbr | pH_out |

| Chemical oxygen demand | mg/L | COD_in | - | COD_out |

| Total dissolved carbon | mg/L | TDC_in | - | TDC_out |

| Dissolved inorganic carbon | mg/L | DIC_in | - | DIC_out |

| Dissolved organic carbon | mg/L | DOC_in | - | DOC_out |

| Total dissolved nitrogen | mg/L | TDN_in | - | TDN_out |

| Polyphenol concentration | mg/L | PPh_in | - | PPh_out * |

| Flow rate | L/d | Flow | - | - |

| Organic loading rate | gCOD/L/d | OLR | - | - |

| Total suspended solids | mg/L | - | TSS_sbr | TSS_out |

| Fixed suspended solids | mg/L | - | FSS_sbr | FSS_out |

| Volatile suspended solids | mg/L | - | VSS_sbr | VSS_out |

| VSS/TSS ratio | - | - | VSS/TSS_sbr | VSS/TSS_out |

| Sludge volume index | mL/g | - | SVI30 | - |

| Turbidity | NTU | - | Turbidity | - |

| Operation time | days | - | Op_t | - |

| Volume | L | - | Vol_sbr | - |

| Volume exchange ratio | % | - | VER | - |

| Hydraulic retention time | days | - | HRT | - |

| Food-to-microorganism ratio | gCOD/gVSS/d | - | FM | - |

| Sludge retention time | days | - | SRT | - |

| COD removal | % | - | - | COD_rmv |

| DOC removal | % | - | - | DOC_rmv |

| TDN removal | % | - | - | TDN_rmv |

| COD | DOC | TDN | Polyphenols | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Removal (%) | 92.0 ± 10.3 | 93.3 ± 6.0 | 89.0 ± 14.8 | 49.8 ± 14.4 |

| Model | Model Pipeline | MAE * (mg/L) | MAPE * (%) | CoV for MAE | CoV for MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENet | Base | 1.08 ± 0.94 | 11.7 ± 12.5 | 0.87 | 1.07 |

| MLPR | Base | 1.44 ± 0.93 | 15.0 ± 11.0 | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| SVR | Base | 1.45 ± 1.26 | 15.6 ± 15.3 | 0.87 | 0.98 |

| ENet | Optimized | 0.94 ± 0.72 | 10.1 ± 8.7 | 0.77 | 0.86 |

| MLPR | Optimized | 0.90 ± 0.73 | 9.4 ± 8.7 | 0.81 | 0.93 |

| SVR | Optimized | 0.88 ± 0.68 | 9.3 ± 8.3 | 0.77 | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva, S.A.; Pirra, A.; Peres, J.A.; Lucas, M.S. Predictive Modeling of Polyphenol Concentration After Sequencing Batch Reactor Winery Wastewater Treatment. Eng. Proc. 2025, 117, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117025

Silva SA, Pirra A, Peres JA, Lucas MS. Predictive Modeling of Polyphenol Concentration After Sequencing Batch Reactor Winery Wastewater Treatment. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 117(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117025

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Sérgio A., António Pirra, José A. Peres, and Marco S. Lucas. 2025. "Predictive Modeling of Polyphenol Concentration After Sequencing Batch Reactor Winery Wastewater Treatment" Engineering Proceedings 117, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117025

APA StyleSilva, S. A., Pirra, A., Peres, J. A., & Lucas, M. S. (2025). Predictive Modeling of Polyphenol Concentration After Sequencing Batch Reactor Winery Wastewater Treatment. Engineering Proceedings, 117(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117025