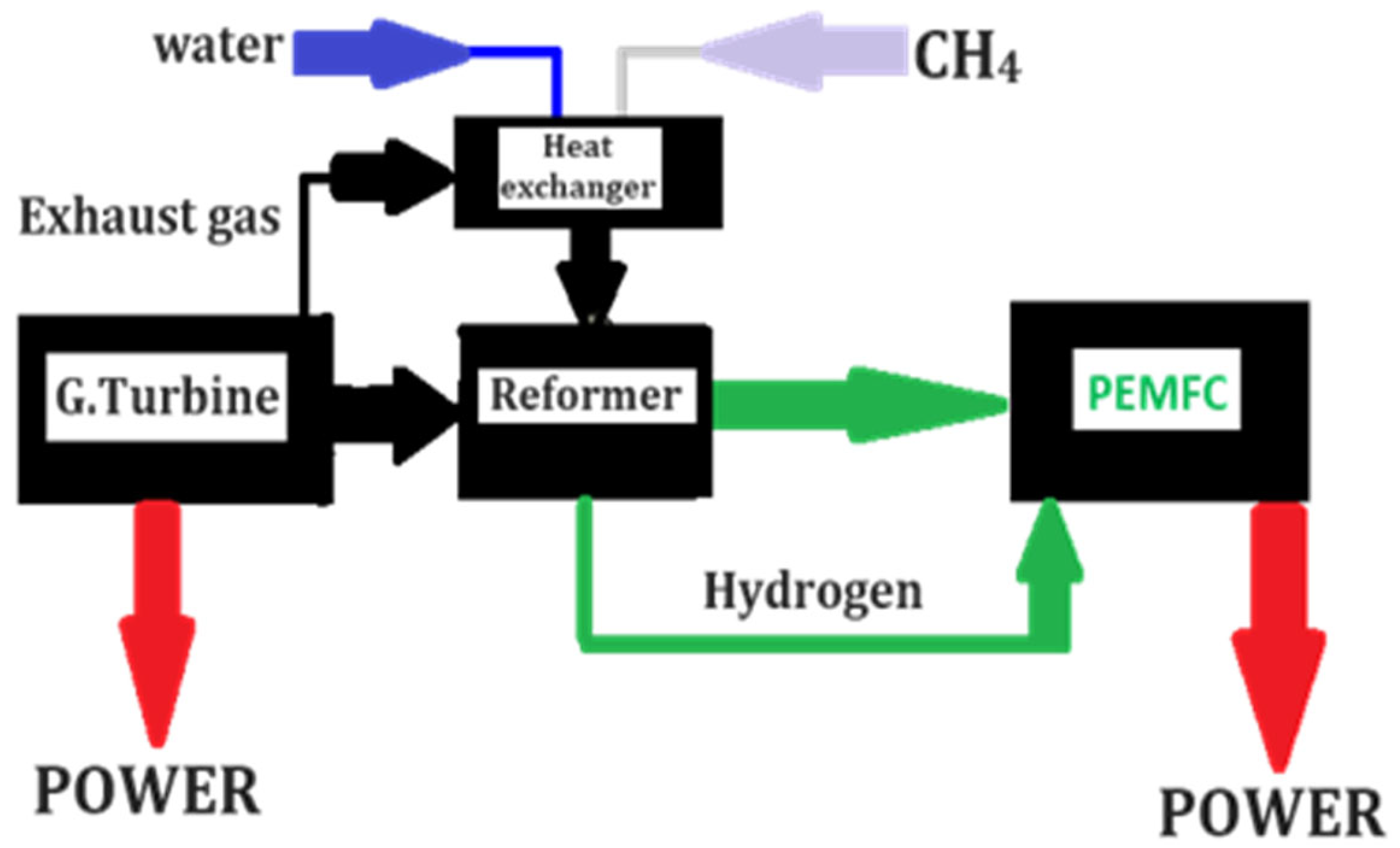

Interface Engineering in Hybrid Energy Systems: A Case Study of Enhance the Efficiency of PEM Fuel Cell and Gas Turbine Integration †

Abstract

1. Introduction

- low temperatures FC: such as Direct Methanol Fuel Cell (DMFC), Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cell (PAFC), and PEMFC.

- high temperatures FC: include molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFC), alkaline fuel cells (AFC), and solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC).

2. Methods and Experimental Study

2.1. System Modelling and Simulation

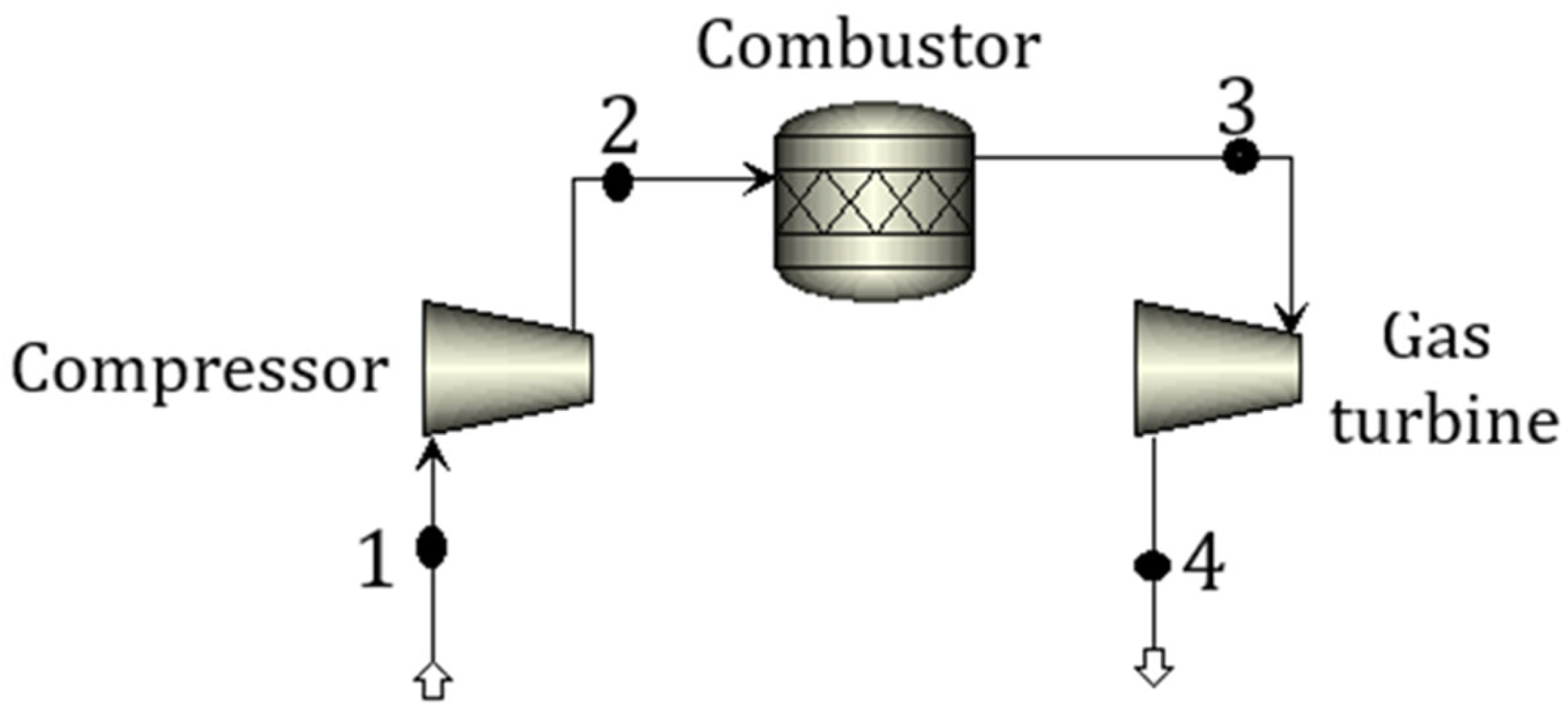

2.2. Description of the Oya Cycle

2.3. Thermodynamic Analysis of the Gas Turbine

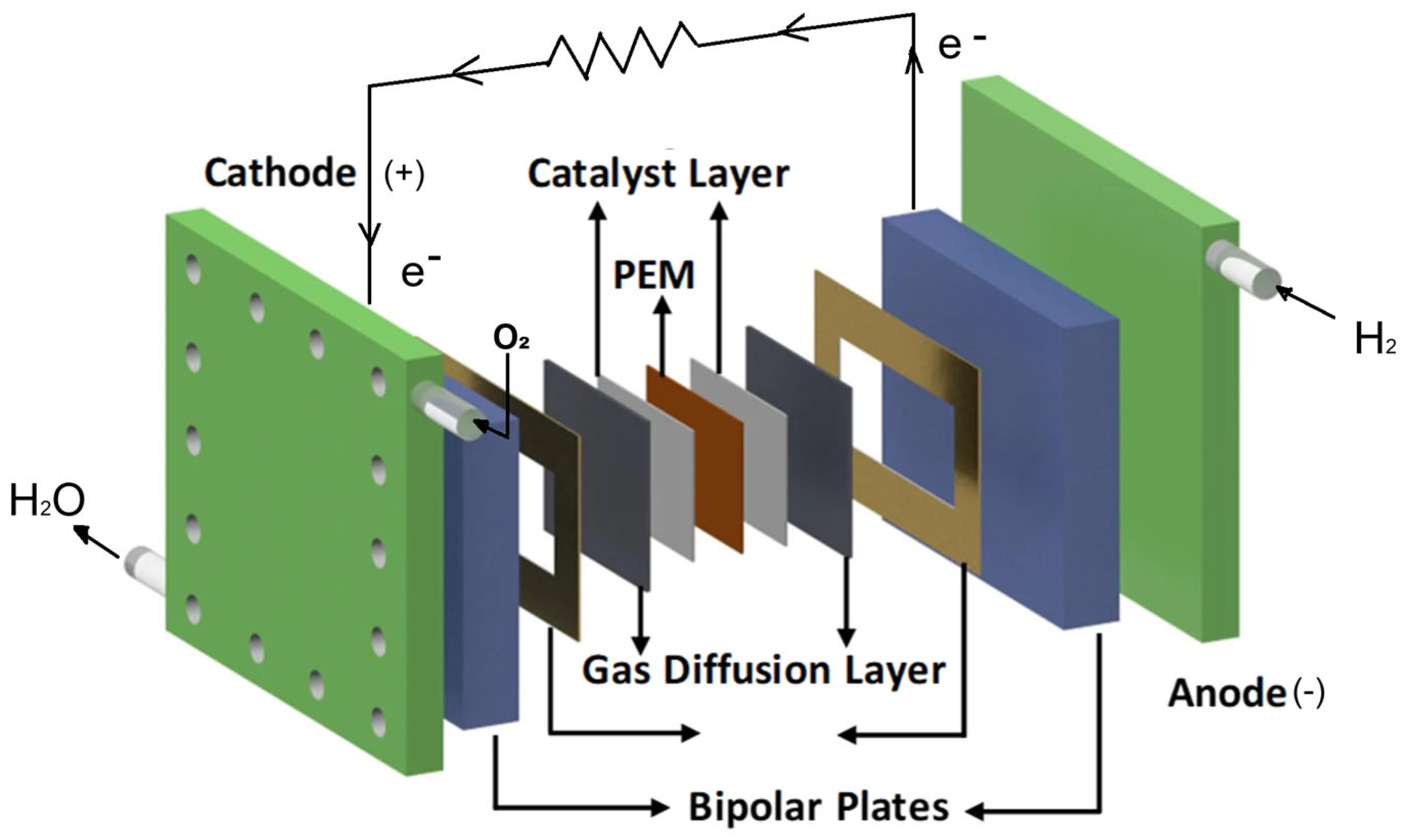

2.4. PEM Fuel Cell Modelling

2.5. Steam Methane Reforming (SMR)

2.6. Reformer Proposed Design and Catalyst Details

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Verification of the Model

3.1.1. Gas Turbine Model Validation

3.1.2. PEM Fuel Cell Model Validation

3.2. Effect of Current Density on PEMFC Performance

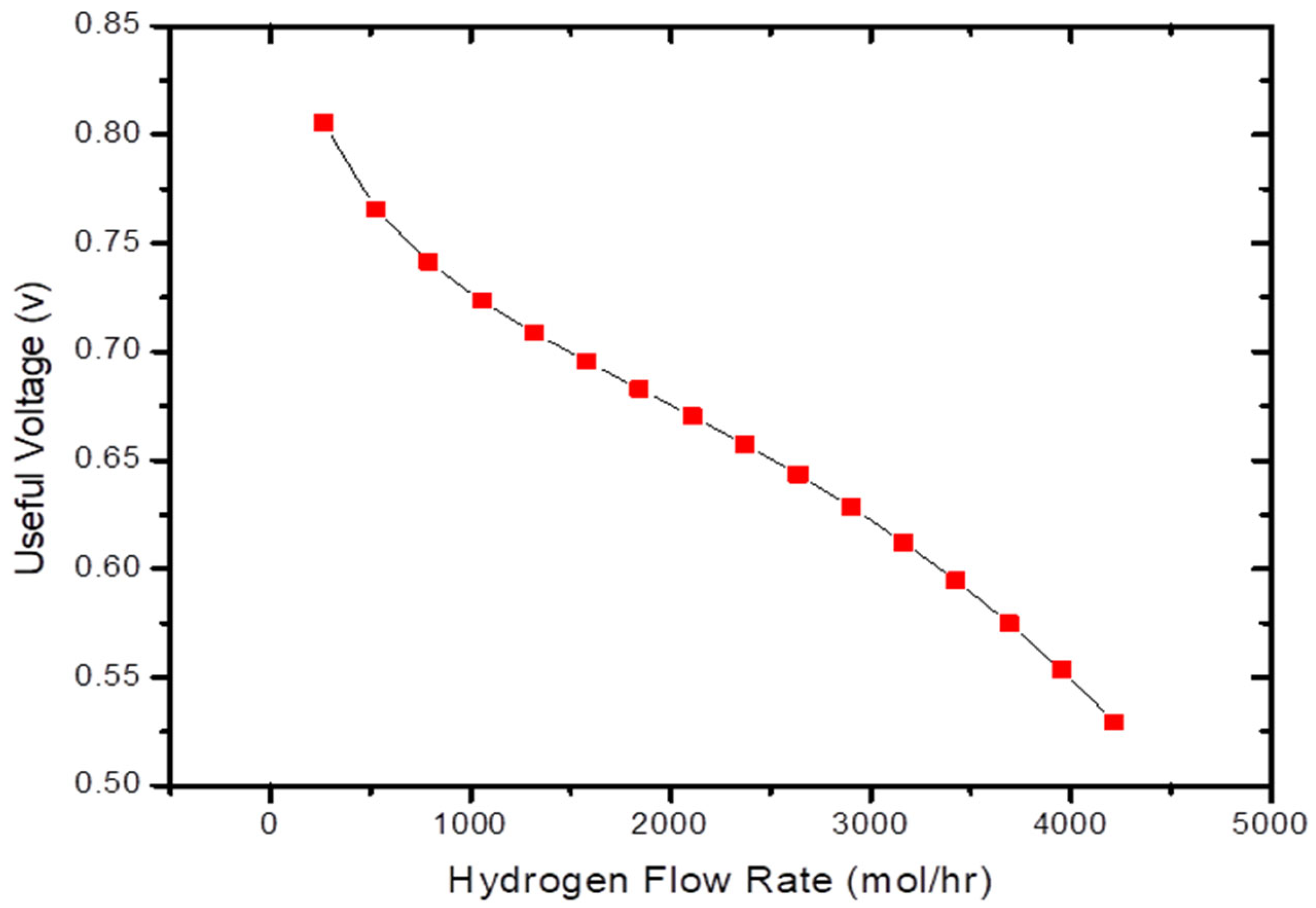

3.3. Hydrogen Flow Rate vs. Cell Voltage

3.4. Polarisation Curve Analysis

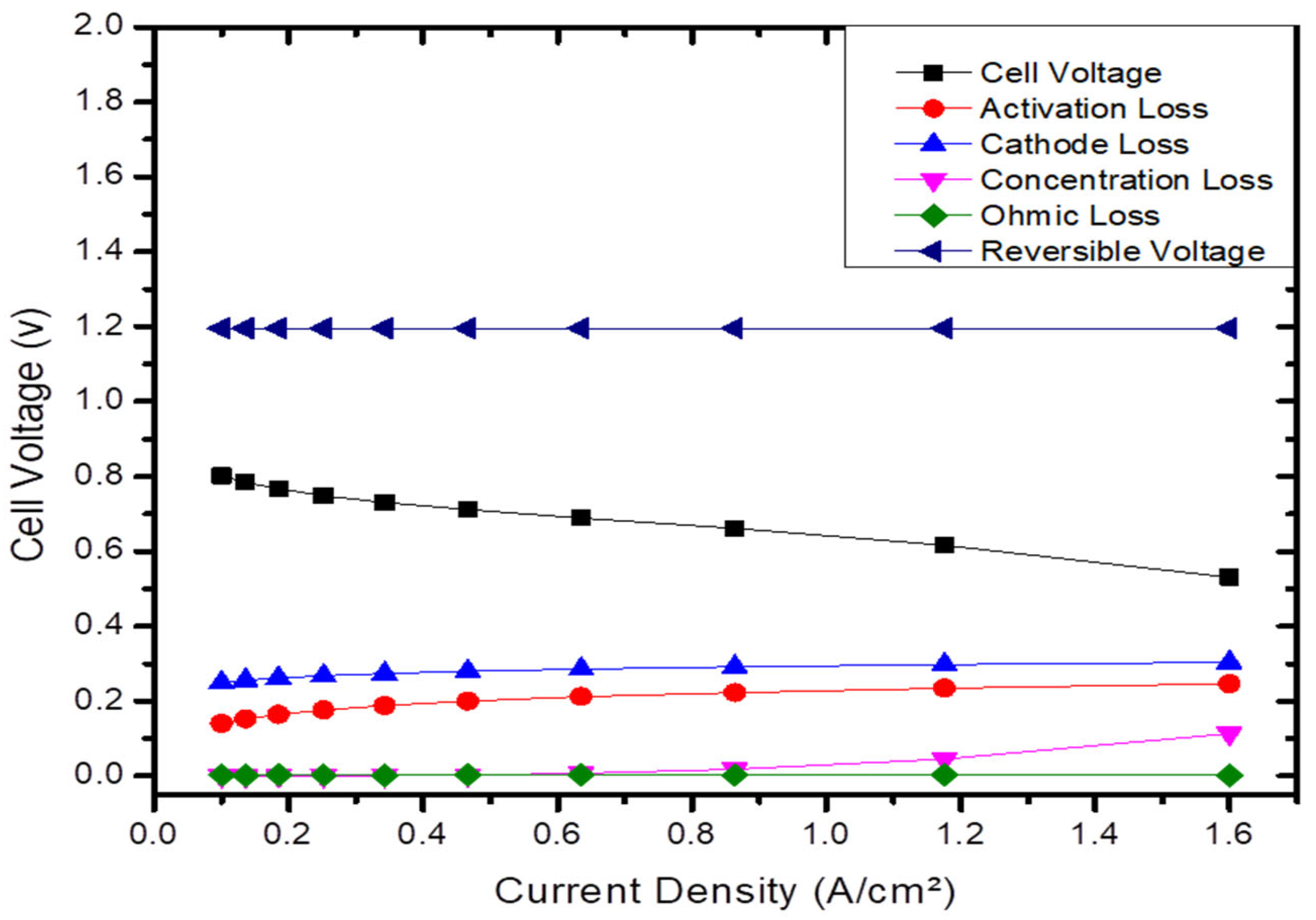

3.5. Voltage Loss Breakdown

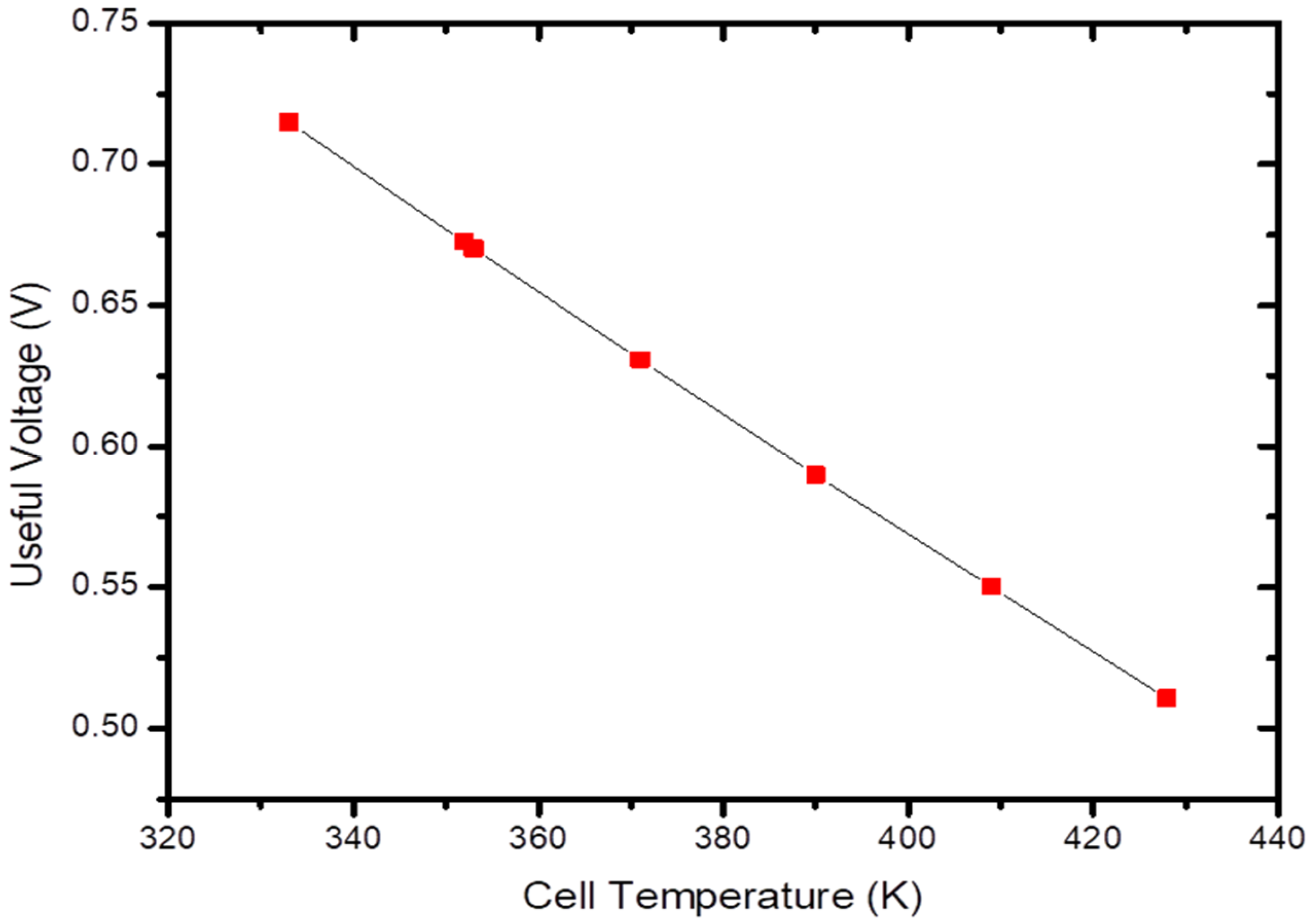

3.6. Temperature Effect on Cell Voltage

3.7. Pressure Effect on Cell Voltage

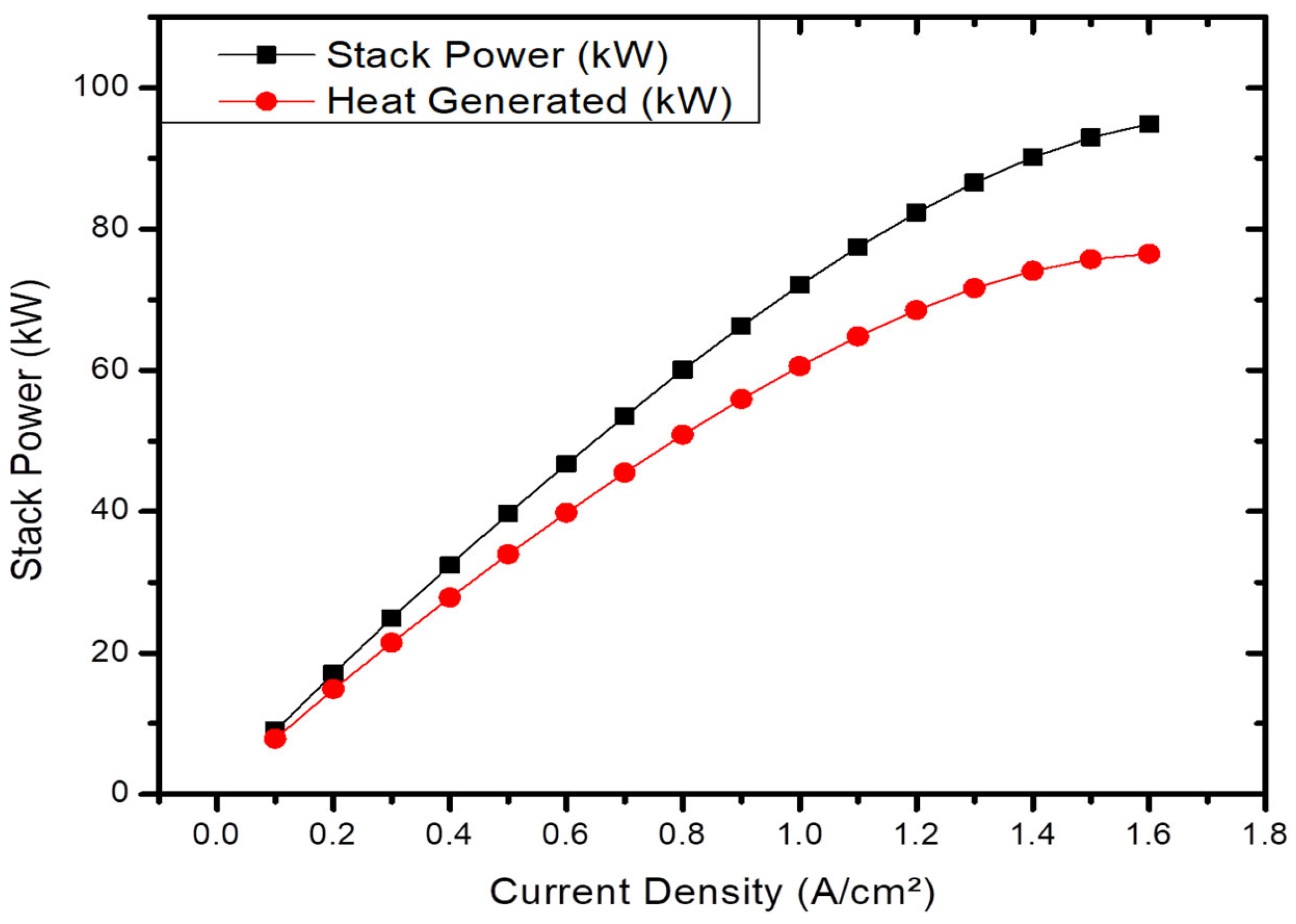

3.8. Current Density vs. Net Power Output

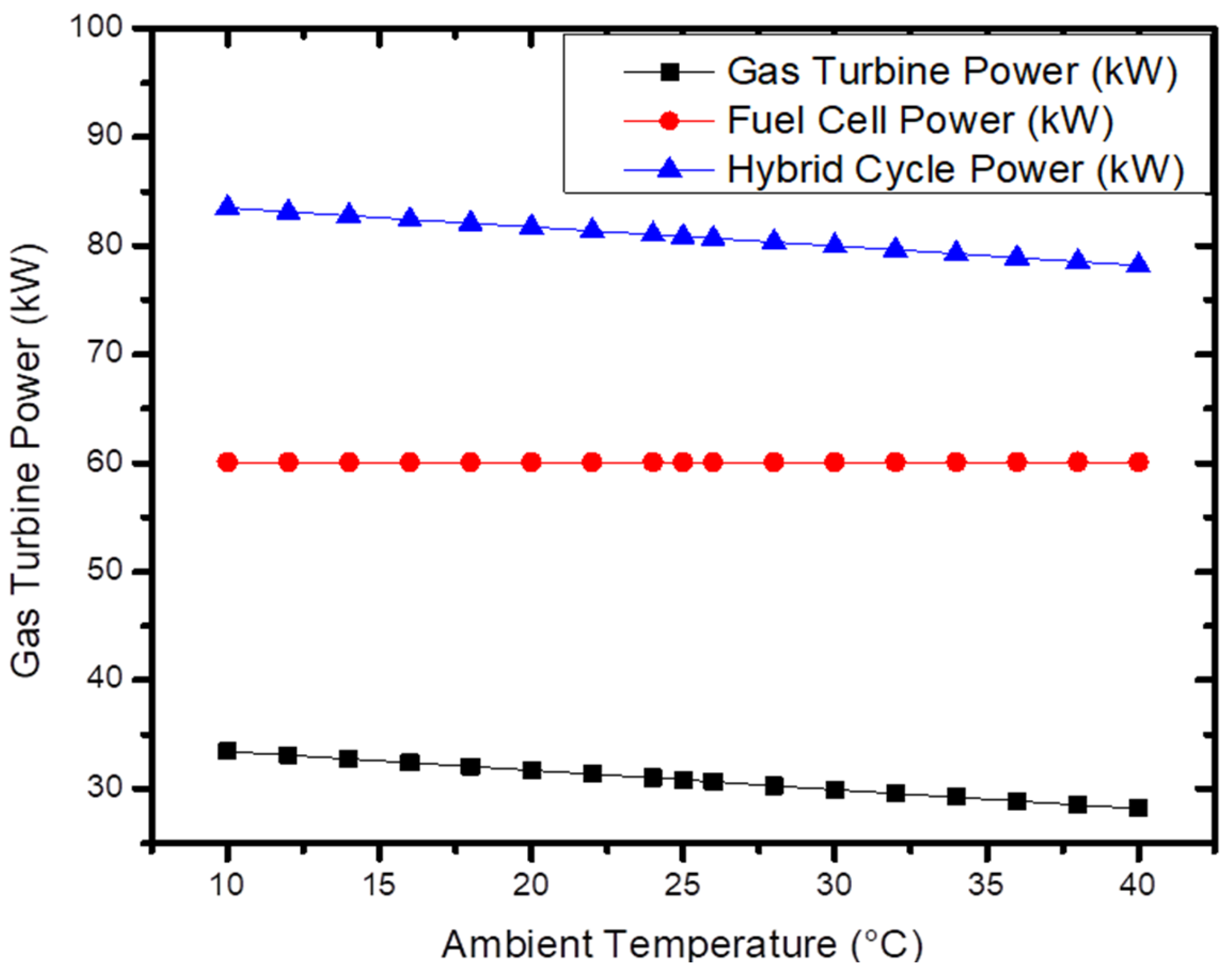

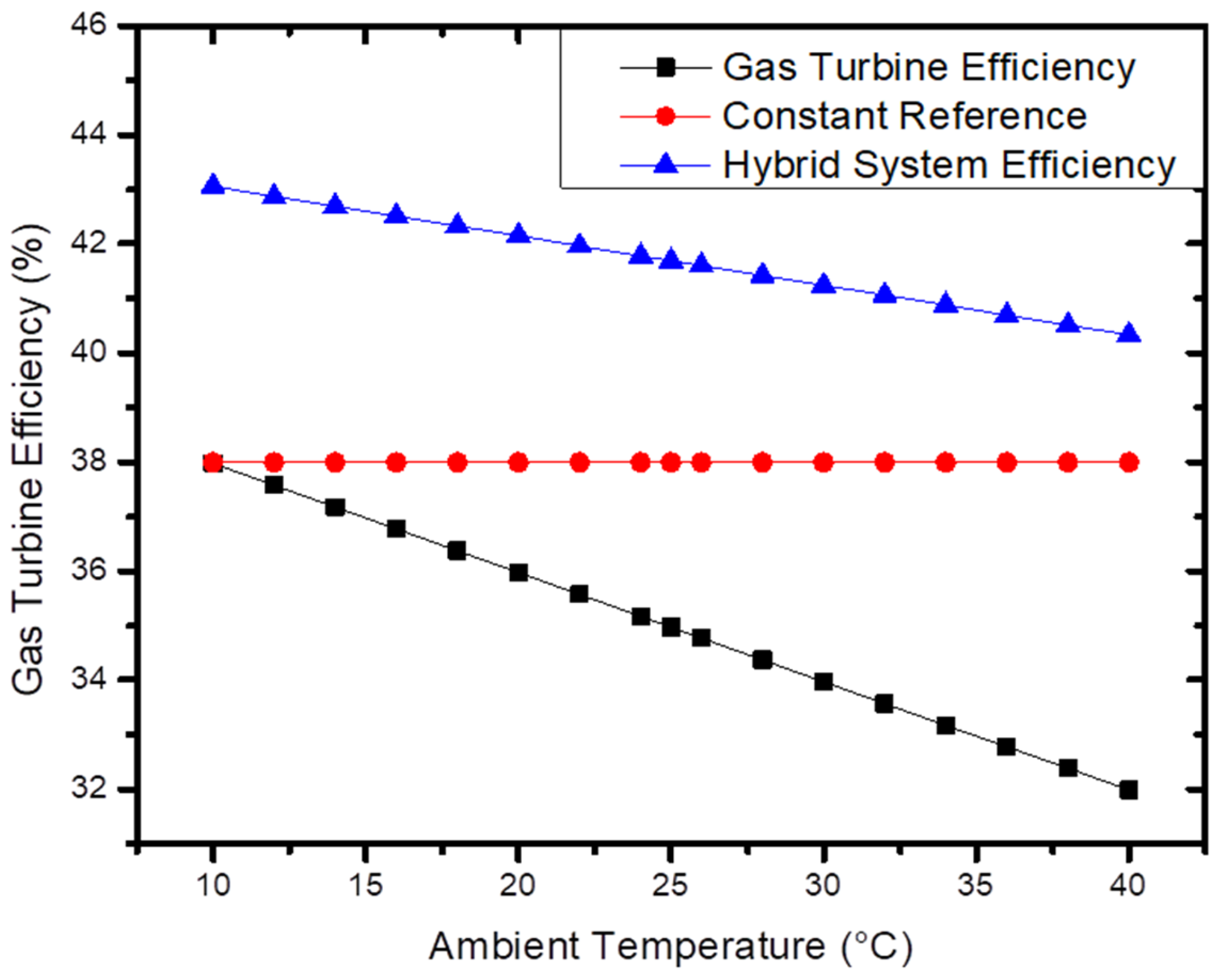

3.9. Ambient Temperature Impact on Gas Turbine and Oya Cycle

3.10. Overall Efficiency Improvement

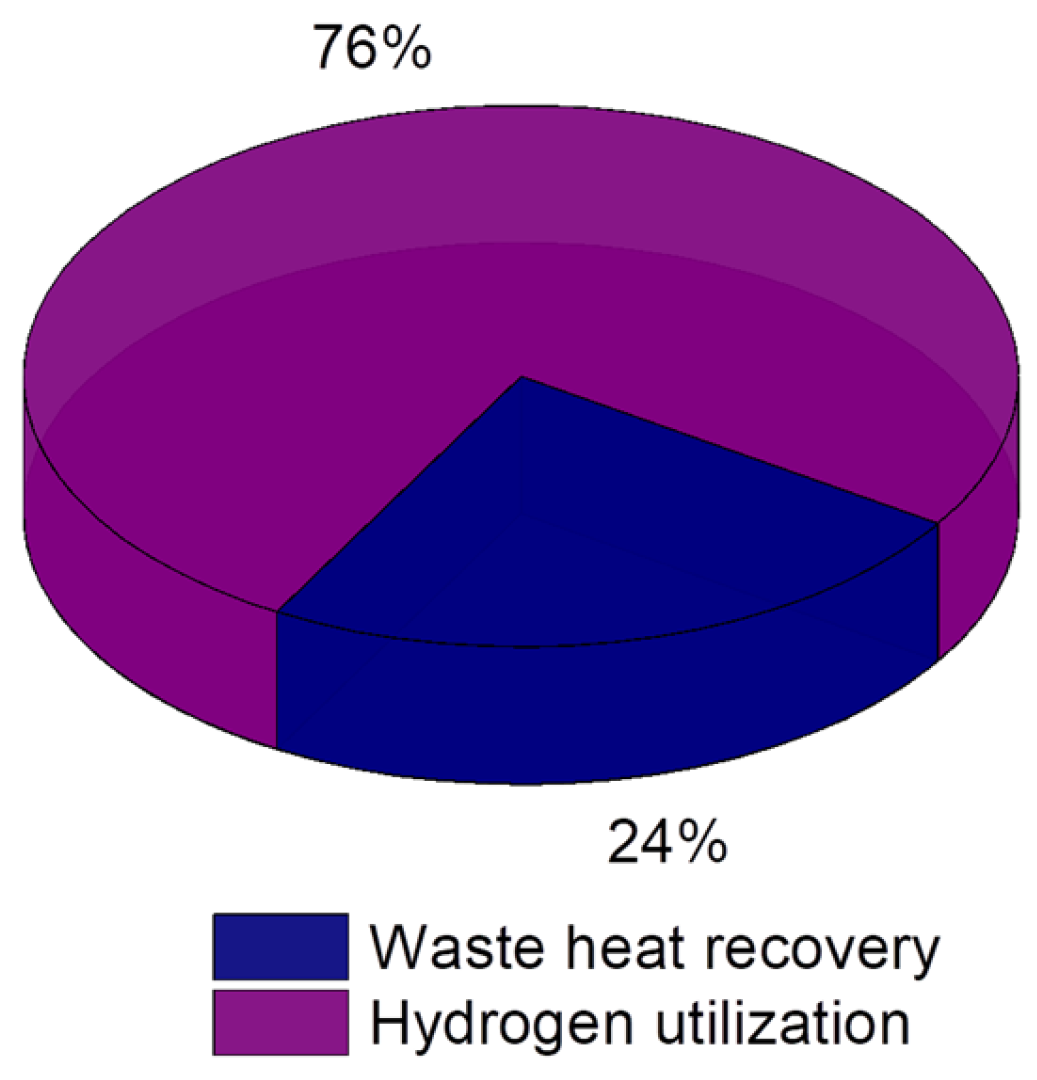

3.11. Breakdown of Efficiency Improvement

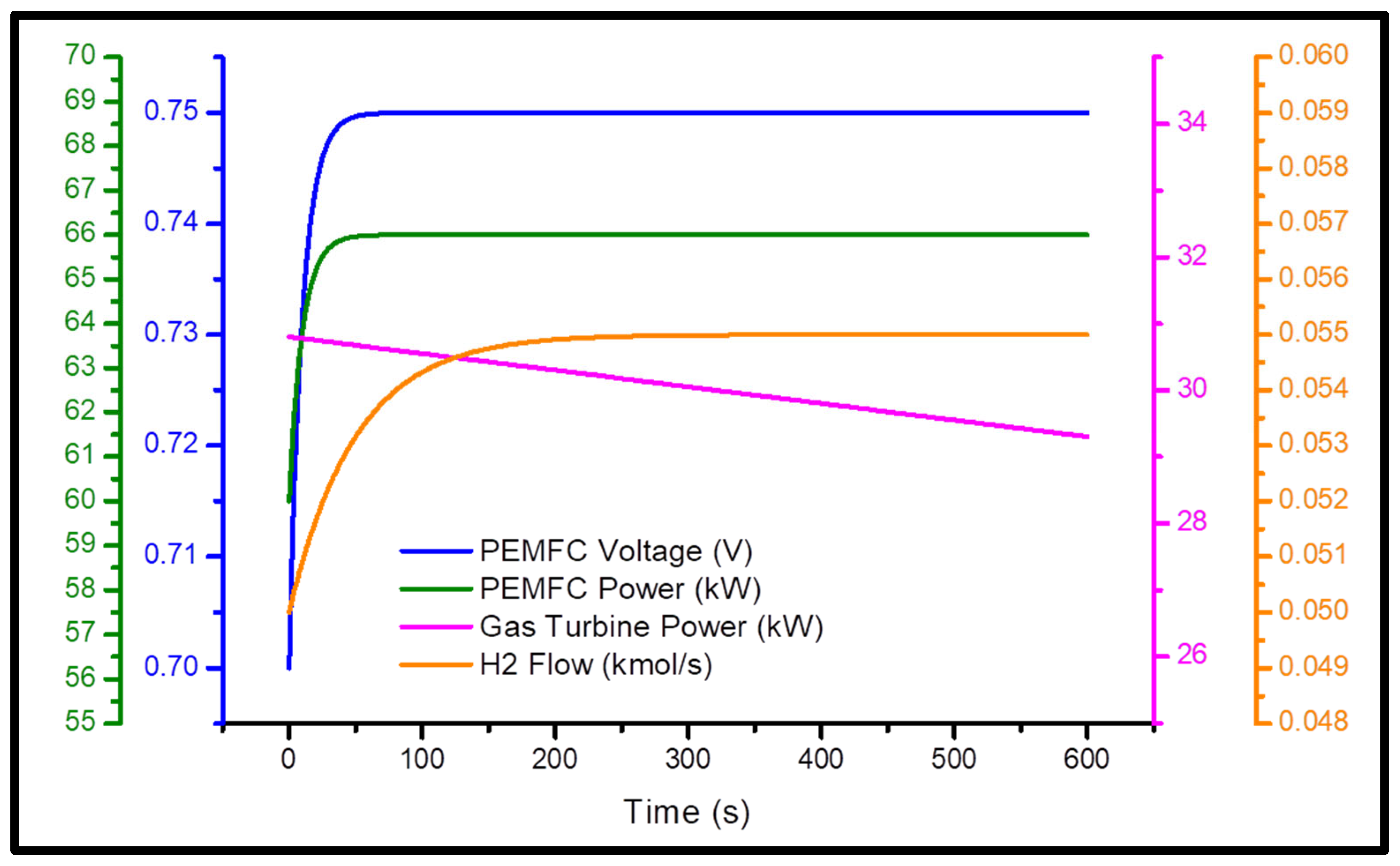

3.12. Preliminary Dynamic Response

3.13. Preliminary Techno-Economic Feasibility Study

4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avevor, J.; Agbale Aikins, S.; Anebi Enyejo, L. Optimizing Gas and Steam Turbine Performance Through Predictive Maintenance and Thermal Optimization for Sustainable and Cost-Effective Power Generation. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2025, 10, 994–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeishi, K.; Krewinkel, R. Advanced Gas Turbine Cooling for the Carbon-Neutral Era. Int. J. Turbomach. Propuls. Power 2023, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, M.H.; Rahaq, Y.; Takita, S.; Zahoor, F.D.; Farmilo, N.; Lewis, O. The Influence of Adding a Functionalized Fluoroalkyl Silanes (PFDTES) into a Novel Silica-Based Hybrid Coating on Corrosion Protection Performance on an Aluminium 2024-T3 Alloy. Mater. Proc. 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takita, S.; Nabok, A.; Lishchuk, A.; Mussa, M.H.; Smith, D. Enhanced Performance Electrochemical Biosensor for Detection of Prostate Cancer Biomarker PCA3 Using Specific Aptamer. Eng 2023, 4, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaq, Y.; Mussa, M.; Mohammad, A.; Wang, H.; Hassan, A. Highly Reproducible Perovskite Solar Cells via Controlling the Morphologies of the Perovskite Thin Films by the Solution-Processed Two-Step Method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 16426–16436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, G.; Capocelli, M.; De Falco, M.; Piemonte, V.; Barba, D. Hydrogen Production via Steam Reforming: A Critical Analysis of MR and RMM Technologies. Membranes 2020, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öberg, S.; Odenberger, M.; Johnsson, F. Exploring the Competitiveness of Hydrogen-Fueled Gas Turbines in Future Energy Systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 624–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaolo, T. Gas Turbine Handbook: Principles and Practice, 5th ed.; River Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781003151821. [Google Scholar]

- Horlock, J.H. A Brief Review of Power Generation Thermodynamics. In Advanced Gas Turbine Cycles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalis, D.P.; Stamatis, A.G. Performance Simulation of a Hybrid Micro Gas Turbine Fuel Cell System Based on Existing Components. In Proceedings of the Volume 4: Cycle Innovations; Fans and Blowers; Industrial and Cogeneration; Manufacturing Materials and Metallurgy; Marine; Oil and Gas Applications; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuge, W. Thermodynamic Analysis of a Hydrogen Fuel Cell Waste Heat Recovery System Based on a Zeotropic Organic Rankine Cycle. Energy 2021, 232, 121038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhav, D.; Wang, J.; Keloth, R.; Mus, J.; Buysschaert, F.; Vandeginste, V. A Review of Proton Exchange Membrane Degradation Pathways, Mechanisms, and Mitigation Strategies in a Fuel Cell. Energies 2024, 17, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.F.; Amphlett, J.C.; Hooper, M.A.I.; Jensen, H.M.; Peppley, B.A.; Roberge, P.R. Development and Application of a Generalised Steady-State Electrochemical Model for a PEM Fuel Cell. J. Power Sources 2000, 86, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukrushpan, J.T.; Peng, H.; Stefanopoulou, A.G. Control-Oriented Modeling and Analysis for Automotive Fuel Cell Systems. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2004, 126, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, A.; Bhatt, V. Hydrogen Production Using Advanced Reactors by Steam Methane Reforming: A Review. Front. Therm. Eng. 2023, 3, 1143987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, M.; Tian, J. Latest Progresses of Ru-Based Catalysts for Alkaline Hydrogen Oxidation Reaction: From Mechanism to Application. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2024, 676, 119684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NREL 2023 Electricity ATB Technologies and Data Overview. Available online: https://atb.nrel.gov/electricity/2023/index (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Kleen, G.; Gibbons, W. Heavy-Duty Fuel Cell System Cost—2023. Available online: https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/docs/hydrogenprogramlibraries/pdfs/review24/24004-hd-fuel-cell-system-cost-2023.pdf?sfvrsn=70ff384f_3 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- NREL 2024 Electricity ATB Technologies. Available online: https://atb.nrel.gov/electricity/2024/technologies (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- U.S. Energy information Administration Natural Gas Prices (Dollars per Thousand Cubic Feet). Available online: https://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/ng_pri_sum_a_epg0_pin_dmcf_m.htm (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Cicgolotti, V.; Genovese, M. Stationary Fuel Cell Applications. Current and Future Technologies Costs, Performances, and Potential 2021. Available online: https://ieafuelcell.com/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

| Symbol | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | Compression ratio | 3.6 | unitless |

| T3 | Turbine inlet temperature | 1117 | K |

| Compressor efficiency | 79.6 | % | |

| Turbine efficiency | 84 | % | |

| Combustion efficiency | 85 | % | |

| Air mass flow rate | 0.3005 | kg/s | |

| Fuel mass flow rate | 1.9582 × 10−3 | kg/s | |

| Total mass flow rate (air + fuel) | 0.302483 | kg/s | |

| T4 | Exhaust gas temperature | 873.272 | K |

| Lower heating value of methane | 45,000 | kJ/kg |

| Symbol | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cells | 400 | Piece | |

| Active area per cell | 200 | cm2 | |

| m | Membrane thickness | 0.0127 | cm |

| ta, tc | Thickness of gas diffusion layers (GDL) | 0.0003 | m |

| Exchange current density (cathode) | A/cm2 | ||

| Exchange current density (anode) | A/cm2 | ||

| Faraday constant | 96,400 | C/mol |

| Symbol | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| T | Operating temperature | 353 | K |

| P | Operating pressure | 3 | Atm |

| Tc | Cathode inlet temperature | 353 | K |

| Ta | Anode inlet temperature | 353 | K |

| Pc | Cathode pressure | 3 | Atm |

| Pa | Anode pressure | 3 | Atm |

| --- | Cathode humidity | 0.9 | % |

| --- | Anode humidity | 0.9 | % |

| Hydrogen excess ratio | 1.25 | unitless | |

| Oxygen excess ratio | 2 | unitless | |

| J | Current density | 0.8 | A/cm2 |

| E | Cell voltage | 0.67 | V |

| Net power output of PEMFC | 60 | kW | |

| Hydrogen flow rate | 2110 | Mol/h | |

| Oxygen flow rate | 8039 | Mol/h |

| Parameter | Assumed Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Micro Gas Turbine Cost | $1200 per kW | Includes turbine, generator, and controls [17]. |

| PEMFC Stack Cost | $1000 per kW | Based on current commercial stack pricing [18]. |

| Reformer & Heat Exchanger | $400 per kW | Covers SMR reactor and thermal integration [17]. |

| Capacity Factor | 0.70 | Typical for distributed generation systems [19]. |

| Fuel Price (Natural Gas) | $6 per MMBtu | Average industrial tariff [20]. |

| System Lifetime | 10 years | Assumes periodic maintenance and overhaul [21]. |

| Operation & maintenance Cost | 3% of capital per year | Includes routine service and consumables [19]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Musa, A.; Al-Glale, G.; Mussa, M.H. Interface Engineering in Hybrid Energy Systems: A Case Study of Enhance the Efficiency of PEM Fuel Cell and Gas Turbine Integration. Eng. Proc. 2025, 117, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117015

Musa A, Al-Glale G, Mussa MH. Interface Engineering in Hybrid Energy Systems: A Case Study of Enhance the Efficiency of PEM Fuel Cell and Gas Turbine Integration. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 117(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117015

Chicago/Turabian StyleMusa, Abdullatif, Gadri Al-Glale, and Magdi Hassn Mussa. 2025. "Interface Engineering in Hybrid Energy Systems: A Case Study of Enhance the Efficiency of PEM Fuel Cell and Gas Turbine Integration" Engineering Proceedings 117, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117015

APA StyleMusa, A., Al-Glale, G., & Mussa, M. H. (2025). Interface Engineering in Hybrid Energy Systems: A Case Study of Enhance the Efficiency of PEM Fuel Cell and Gas Turbine Integration. Engineering Proceedings, 117(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117015