1. Introduction

Photoplethysmography (PPG) is a non-invasive optical technique that measures blood volume changes in the microvascular bed [

1]. At each cardiac cycle, the pressure wave generated by the heart causes a transient increase in peripheral blood volume, followed by an outflow during cardiac relaxation [

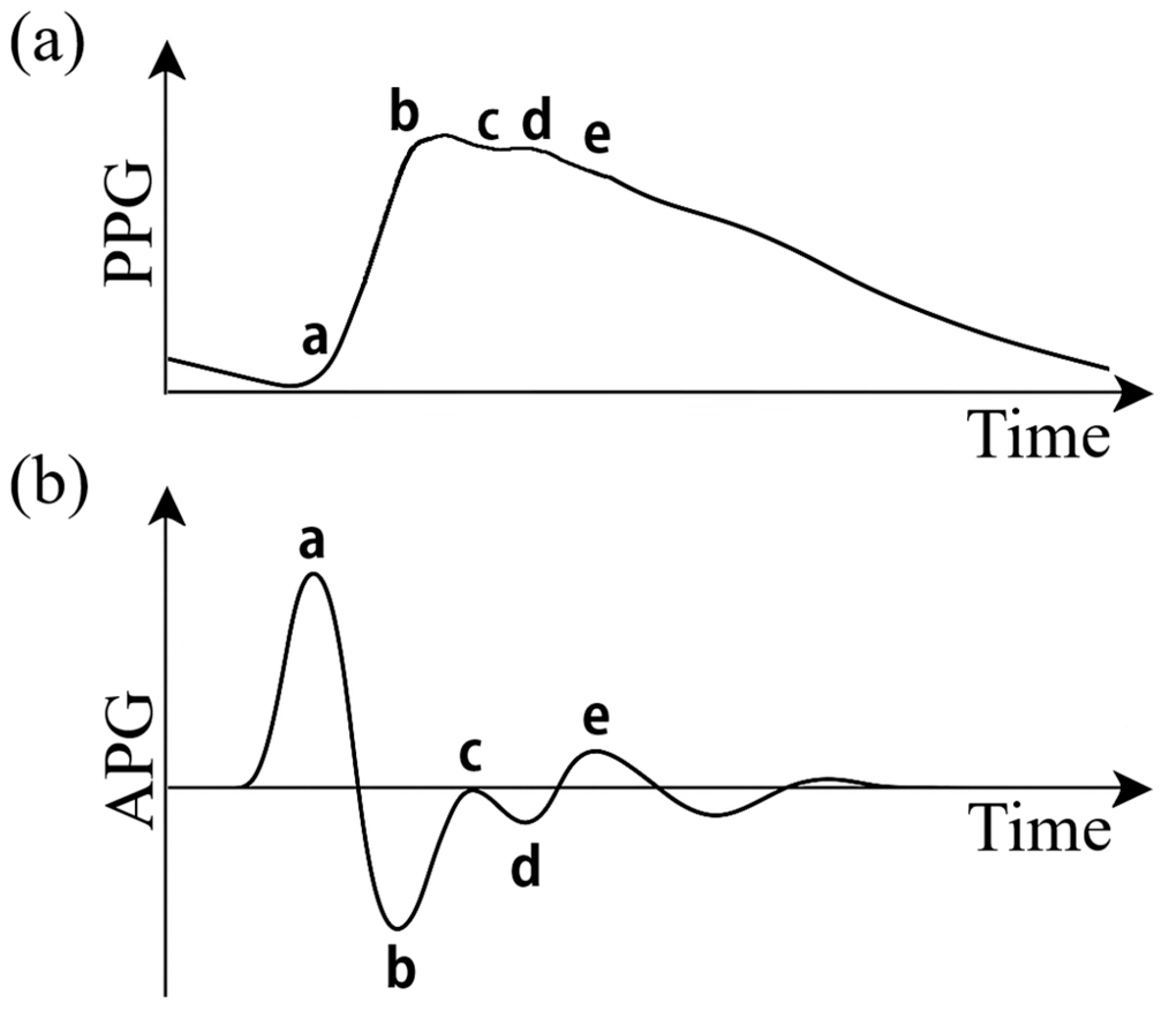

2]. The resulting PPG signal (

Figure 1a) is a pulsatile wave characterized by a rapid systolic rise, i.e., a peak corresponding to the maximum blood volume (systolic wave), and a descending phase with a small notch due to aortic valve closure (dicrotic notch) [

3], followed by a minor wave in diastole (dicrotic wave). In summary, the PPG signal represents the arterial pulse in time and provides indirect information on blood pressure and perfusion [

4].

PPG sensors consist of an LED and a photodetector; they are extremely compact and have low costs [

5], so they can be easily integrated into commercial devices such as smartwatches and smartbands in order to detect physiological signals such as heart rate and blood oxygenation [

6]. Despite their advantages, PPG sensors have unexplored potential, and particularly in recent years, there has been an increasing growth in the study and research of these sensors in order to achieve non-invasive assessment of vascular health status [

7,

8,

9]. For example, recent works have focused on the estimation of arterial stiffness by advanced PPG signal analysis [

10].

One of the most common techniques on the processing of these signals is the analysis of the second derivative of the PPG signal (SDPPG), also called photoplethysmographic acceleration (APG) [

11,

12]. This mathematical transformation (

Figure 1b) highlights inflection points and rapid changes in the wave, allowing more precise detection of morphological details that are often difficult to detect in the raw signal. APG provides information on the structural and functional properties of both large caliber and peripheral arteries and has been widely used for the assessment of vascular stiffness and aging [

13].

The APG waveform typically has five characteristic deflections, conventionally labeled a, b, c, d and e [

14]. Each of these corresponds to specific physiological phases of the pulsatile cycle: the a wave is the first wave and represents a pronounced positive peak due to the onset of systole; the b wave represents a slowing or deceleration of blood flow immediately after the initial systolic peak; the c wave is the second positive wave physiologically attributed to the reflected back wave arriving from the periphery; wave d is the second negative wave that marks the end of the active systole phase and coincides with the dicrotic notch, i.e., at the abrupt drop in pressure caused by aortic valve closure; wave e is a third positive wave that appears during the initial phase of diastole [

15]. Numerous indices of cardiovascular health are derived from combinations or ratios between these amplitudes [

16,

17].

In the present work, the d/a relationship is investigated in two experimental settings: an in vitro study using PPG signals acquired on commercial silicone phantom models with different stiffnesses, representative of healthy and pathological vascular conditions, and an in vivo study in which PPG signals acquired on volunteers of different ages are considered. In both cases, the aim is to evaluate the correlation between the d/a parameter and arterial stiffness, testing its potential as a non-invasive index of vascular health.

2. Materials and Methods

Photoplethysmographic signals were acquired using a single PPG sensor (DFRobot; Beijing, China) operating at 520 nm, connected to an NI USB-6009 acquisition board (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) with a sampling rate of 5000 Hz. Acquisition management was accomplished by a dedicated algorithm implemented in LabVIEW (v.2021, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA).

For the in vitro study, two flexible silicone models with a length of 50 cm and an inner radius of 8 mm and characterized by Young’s modulus of 2.7 MPa (Model 1) and 5.4 MPa (Model 2) were used, representing, respectively, a physiological vascular condition and a pathological condition with increased stiffness. The sensor was placed at the midpoint of each model. To simulate the cardiovascular conditions, the two models were placed in a flow duplicator, as described in previous studies [

18,

19], set to ensure a flow rate of 5 liters/minute, a heart rate of 90 beats/minute, and an arterial pressure between 70 and 120 mmHg. Distilled water (density: 1000 kg/m

3; viscosity: 0.7 mPa·s) was used as the fluid. For each model, five signals lasting three minutes each were acquired. For each acquisition, the average d/a ratio was calculated over one-minute intervals, resulting in a total of 15 samples per model, which were subsequently used for statistical comparison between the two conditions.

For the in vivo study, nine healthy volunteers (6 males and 3 females) aged 42.1 ± 15.2 years with no known cardiovascular disease were recruited. For each participant, three acquisitions lasting three minutes each were performed by placing the PPG sensor on the index finger. For each acquisition, the mean d/a ratio was calculated over one-minute intervals. Since there was no direct measure of arterial stiffness for each individual, the d/a ratio was related to the age of the participants, considering that increasing age is generally associated with an increase in arterial stiffness [

20].

Data processing was performed with MATLAB (v.2022b, The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Initially, the raw signals were filtered using a fourth-order Butterworth IIR bandpass filter with cutoff frequencies between 0.5 Hz and 5 Hz to remove low-frequency artifacts and high-frequency noise. Next, the second derivative of the filtered PPG signal was calculated. Automatic identification of the fiducial points a, b, c, d and e of the second derivative was performed using MATLAB’s findpeaks function, identifying local maxima and minima within time windows consistent with the cardiac cycle. The d/a amplitude ratio was therefore calculated, which was used as an index of arterial stiffness for both the in vitro and the in vivo study.

3. Results

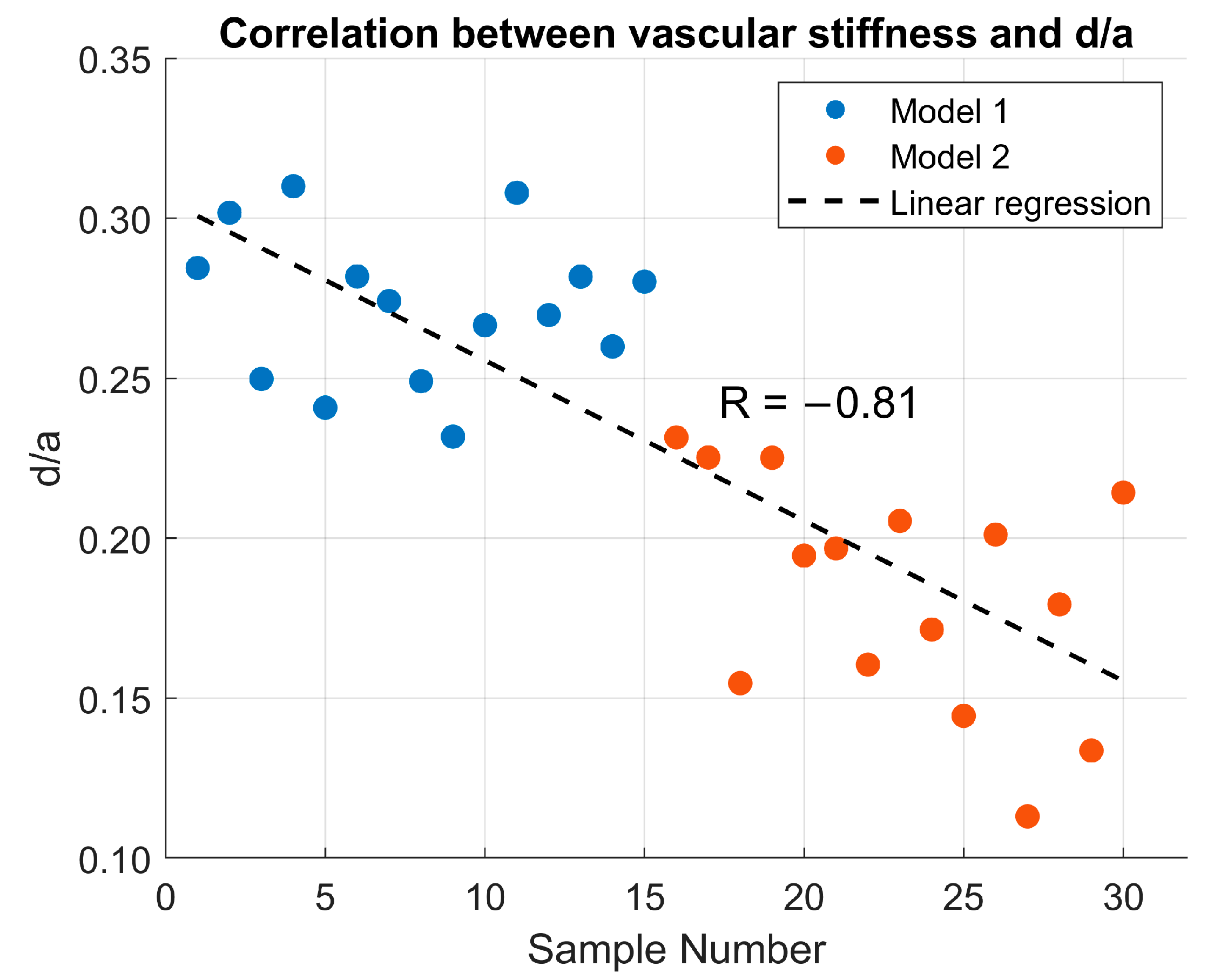

Figure 2 shows the correlation between the d/a ratio and vascular stiffness in the in vitro study using two silicone phantom models. Model 1 (physiological) exhibited a mean d/a value of 0.277 ± 0.036, while Model 2 (pathological) showed a mean value of 0.183 ± 0.036. Linear regression analysis yielded a correlation coefficient of R = −0.81, indicating a strong negative correlation between vascular stiffness and the d/a ratio.

Figure 3 presents the correlation between age and the d/a ratio in the in vivo study. Participant ages ranged from 26 to 63 years, with corresponding d/a values ranging from −0.120 to −0.410. Linear regression analysis revealed a correlation coefficient of R = −0.90, confirming a strong negative correlation between age and the d/a ratio.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in both the in vitro and in vivo studies support the hypothesis that the d/a ratio, derived from the second derivative of the PPG signal, can be used as an indirect indicator of arterial stiffness. It is important to note that, in the absence of direct measurements of arterial stiffness for each participant, age was used as a surrogate marker, based on its well-established association with increased vascular rigidity [

21].

In the in vitro study, silicone phantom models with different mechanical properties produced significantly different d/a values. Model 1 systematically showed higher d/a values than the more rigid phantom, with a strong negative correlation (R = −0.81) between stiffness and d/a ratio. An important observation is that in the silicone models, the values of d/a ratio are positive in both stiffness conditions. This behavior can be attributed to the simplified nature of the model, i.e., the absence of vascular tone, branching, and energy dissipation, which causes the reflected wave to arrive at a phase of the cycle where the second derivative remains positive. Furthermore, the use of distilled water as the working fluid, which has a lower viscosity than blood, reduces wave attenuation and maintains the relative amplitude of d point. Consequently, although the increase in stiffness leads to a reduction in the d/a ratio, the values remain positive in both experimental conditions.

The in vivo results showed a similar trend, with a strong and major negative correlation (R = −0.90): younger participants had higher d/a values, while in older subjects the ratio was progressively reduced. This is consistent with the age-related increase in arterial stiffness, widely documented in the literature [

22,

23], which modifies the pulse wave propagation velocity and reflection characteristics, thus altering the morphology of the PPG signal and its derivatives. The results of the in vivo study are also consistent with those reported by Inoue et al. [

24], who, analyzing a population of women aged between 50 and 79 years, observed the same negative correlation between d/a ratio and stiffness, with values very similar to those found in the present study. Similarly, Takazawa et al. [

25] reported the same trend in a study of 39 patients (mean age 54 ± 11 years), confirming the robustness of the association between a reduction in the d/a ratio and an increase in arterial stiffness. However, it is important to recognize that several external factors can influence the amplitude and morphology of the measured PPG signals, potentially affecting the estimation of the d/a ratio. Previous studies have shown that signal quality is highly dependent on sensor placement and contact pressure, as both insufficient and excessive preload can reduce pulse amplitude and distort systolic and diastolic peaks [

26,

27]. In addition, skin tone, tissue composition, and the distance between the sensor and the artery have been reported as relevant sources of variability [

28]. In this regard, while the present study was conducted under controlled in vitro and in vivo conditions, future investigations should address these influencing factors to further strengthen the robustness and applicability of the d/a ratio in more practical monitoring scenarios.

In conclusion, unlike previous studies that examined the d/a ratio exclusively in clinical settings, this work adopts a dual experimental approach that integrates the acquisition and validation of in vitro and in vivo tests. The use of silicone phantoms with known stiffness allows for accurate assessment of the relationship between d/a ratio and vascular stiffness, while in vivo data confirm its relevance under physiological conditions. Combined in vitro and in vivo data indicate that the d/a ratio is a promising index for non-invasive assessment of vascular health, with potential applications in wearable monitoring systems for early detection of arterial stiffness. Future studies should aim to validate this index against standard measures of stiffness and explore its sensitivity in clinical populations with cardiovascular risk factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D., F.S., S.P. and L.D.; methodology, G.D.; software, G.D. and F.S.; validation, G.D. and F.S.; formal analysis, G.D.; investigation, G.D., F.S. and S.P.; resources, F.S., S.P. and L.D.; data curation, G.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, G.D., F.S., S.P. and L.D.; visualization, G.D. and F.S.; supervision, F.S., S.P. and L.D.; project administration, F.S. and L.D.; funding acquisition, L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen, J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol. Meas. 2007, 28, R1–R39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mynard, J.P.; Kondiboyina, A.; Kowalski, R.; Cheung, M.M.H.; Smolich, J.J. Measurement, Analysis and Interpretation of Pressure/Flow Waves in Blood Vessels. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamrah, M.A.; Xu, J.; El Sawy, A.; Aguib, H.; Yacoub, M.; Parker, K.H. Mechanics of the dicrotic notch: An acceleration hypothesis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H 2020, 234, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Mejía, E.; Allen, J.; Budidha, K.; El-Hajj, C.; Kyriacou, P.A.; Charlton, P.H. Photoplethysmography Signal Processing and Synthesis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 69–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardulla, F.; Cosoli, G.; Gnoffo, C.; Antognoli, L.; Bongiorno, F.; Diana, G.; Scalise, L.; D’Acquisto, L.; Arnesano, M. Experimental Analysis on the Effect of Contact Pressure and Activity Level as Influencing Factors in PPG Sensor Performance. Sensors 2025, 25, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardulla, F.; Riggi, C.; Diana, G.; D’Acquisto, L. Preliminary Analisys on the Effect of Skin Temperature on Photoplethysmographic Signal. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEnv), Chania, Greece, 12–14 June 2024; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, P.H.; Kyriaco, P.A.; Mant, J.; Marozas, V.; Chowienczyk, P.; Alastruey, J. Wearable Photoplethysmography for Cardiovascular Monitoring. Proc. IEEE Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 110, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommermeyer, D.; Zou, D.; Ficker, J.H.; Randerath, W.; Fischer, C.; Penzel, T.; Sanner, B.; Hedner, J.; Grote, L. Detection of cardiovascular risk from a photoplethysmographic signal using a matching pursuit algorithm. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2016, 54, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.H.; Baur, S.; Daswani, M.; Chen, C.; Harrell, L.; Kakarmath, S.; Jabara, M.; Behsaz, B.; McLean, C.Y.; Matias, Y.; et al. Predicting cardiovascular disease risk using photoplethysmography and deep learning. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour, P.; May, J.M.; Kyriacou, P.A. Photoplethysmography for the Assessment of Arterial Stiffness. Sensors 2023, 23, 9882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendi, M.; Jonkman, M.; De Boer, F. Applying the APG to measure Heart Rate Variability. In Proceedings of the 2010 the 2nd International Conference on Computer and Automation Engineering (ICCAE), Singapore, 26–28 February 2010; pp. 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Lee, J.M.; Kwon, S.H. Association of the second derivative of photoplethysmogram with age, hemodynamic, autonomic, adiposity, and emotional factors. Medicine 2019, 98, e18091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohjitani, A.; Miyata, M.; Iwase, Y.; Sugiyama, K. Responses of the second derivative of the finger photoplethysmogram indices and hemodynamic parameters to anesthesia induction. Hypertens Res. 2012, 35, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendi, M.; Jonkman, M.; DeBoer, F. Heart Rate Variability and the Acceleration Plethysmogram Signals Measured at Rest. In Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies. BIOSTEC 2010. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Fred, A., Filipe, J., Gamboa, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha Sardana, H.K.; Dahiya, N.; Dogra, N.; Kanawade, R.; Sharma, Y.P.; Kumar, S. Automated myocardial infarction and angina detection using second derivative of photoplethysmography. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2023, 46, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendi, M.; Jost, E.; Alian, A.; Fletcher, R.R.; Bomberg, H.; Eichenberger, U.; Menon, C. Photoplethysmography Features Correlated with Blood Pressure Changes. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, D.; Esparza, A.; Ghamari, M.; Soltanpur, C.; Nazeran, H. A review on wearable photoplethysmography sensors and their potential future applications in health care. Int. J. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018, 4, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, G.; Scardulla, F.; Puleo, S.; Pasta, S.; D’Acquisto, L. A Preliminary Study on Arterial Stiffness Assessment Using Photoplethysmographic Sensors. Eng. Proc. 2024, 82, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, G.; Scardulla, F.; Puleo, S.; Pasta, S.; D’Acquisto, L. Non-Invasive Estimation of Arterial Stiffness Using Photoplethysmography Sensors: An In Vitro Approach. Sensors 2025, 25, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, J.C.; Lampi, M.C.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Age-related vascular stiffening: Causes and consequences. Front Genet. 2015, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos, J.A. Arterial stiffness: Basic concepts and measurement techniques. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2012, 5, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebre, Y.T.; Yakubov, E.; Wong, W.T.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Sayed, N.; Sikora, A.G.; Bonnen, M.D. Vascular Aging: Implications for Cardiovascular Disease and Therapy. Transl. Med. 2016, 6, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Rahman, A.A.; Lee, S.; Malhotra, R. The Implications of Aging on Vascular Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, N.; Kawakami, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Ito, C.; Fujiwara, S.; Sasaki, H.; Kihara, Y. Second derivative of the finger photoplethysmogram and cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged and elderly Japanese women. Hypertens Res. 2017, 40, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takazawa, K.; Tanaka, N.; Fujita, M.; Matsuoka, O.; Saiki, T.; Aikawa, M.; Tamura, S.; Ibukiyama, C. Assessment of vasoactive agents and vascular aging by the second derivative of photoplethysmogram waveform. Hypertension 1998, 32, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scardulla, F.; Cosoli, G.; Antognoli, L.; Gnoffo, C.; Diana, G.; Bongiorno, F.; Scalise, L.; D’ACquisto, L.; Arnesano, M. Experimental Analysis on the Effect of Contact Pressure, Activity Level, and Skin Tone as Influencing Factors in PPG Sensors Performance. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEnv), Venezia, Italy, 11–13 June 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C.; Silvestri, S.; Schena, E.; Massaroni, C. Smart wristband based on a magnetic soft sensor for pulse wave measurement. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 37142–37150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taffoni, F.; Rivera, D.; La Camera, A.; Nicolò, A.; Velasco, J.R.; Massaroni, C. A Wearable System for Real-Time Continuous Monitoring of Physical Activity. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 1878354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).