Application of Reduced Graphene Oxide in Biocompatible Composite for Improving Its Specific Electrical Conductivity †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods and Materials

2.1. Manufacturing of a Dispersed Medium of Collagen/BSA/Chitosan/SWCNT/rGO/Eosin Y

2.2. Photopolymerization

2.3. Determination of Specific Conductivity

2.4. Determination of Biocompatibility

3. Results and Discussions

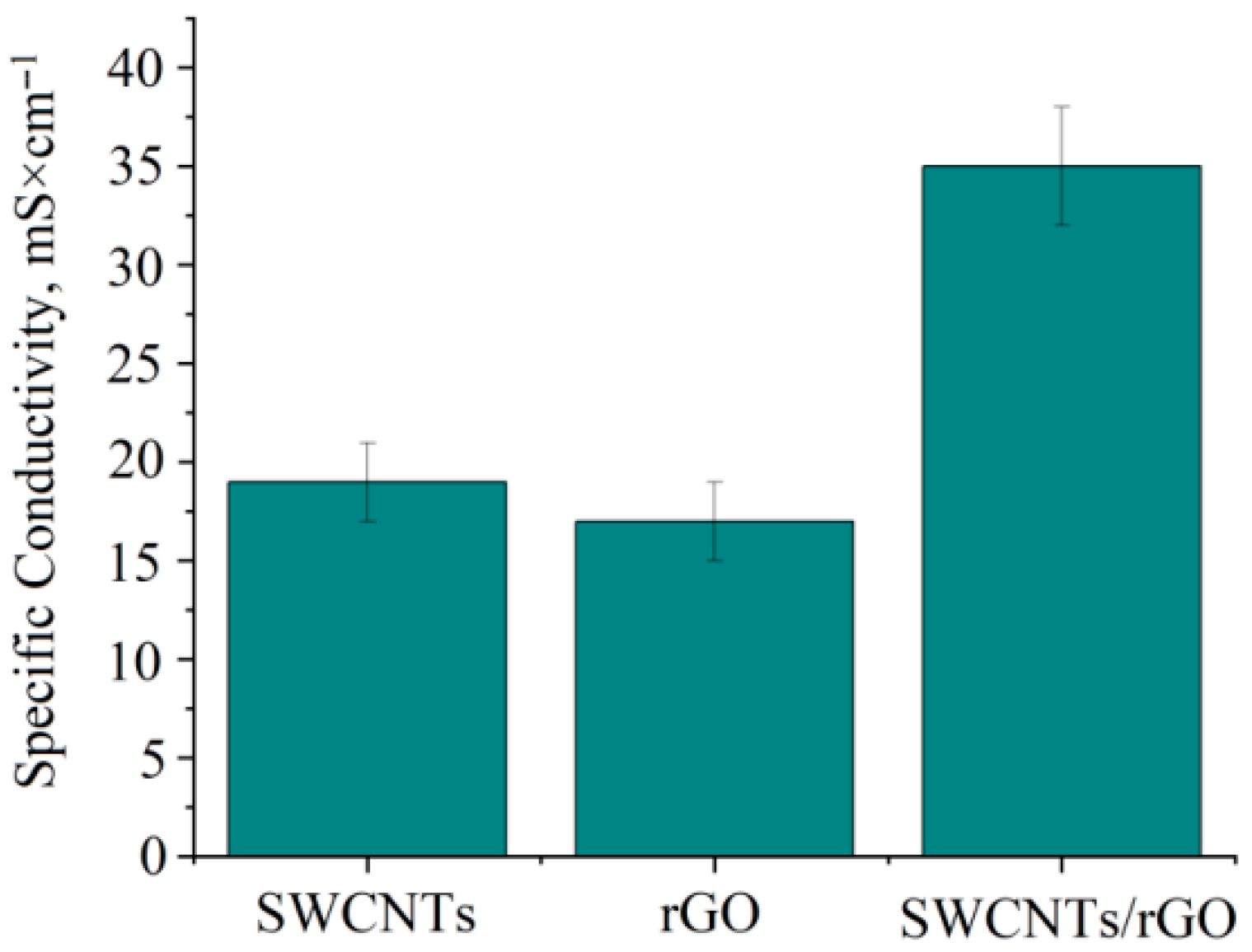

3.1. Electrical Conductivity Properties

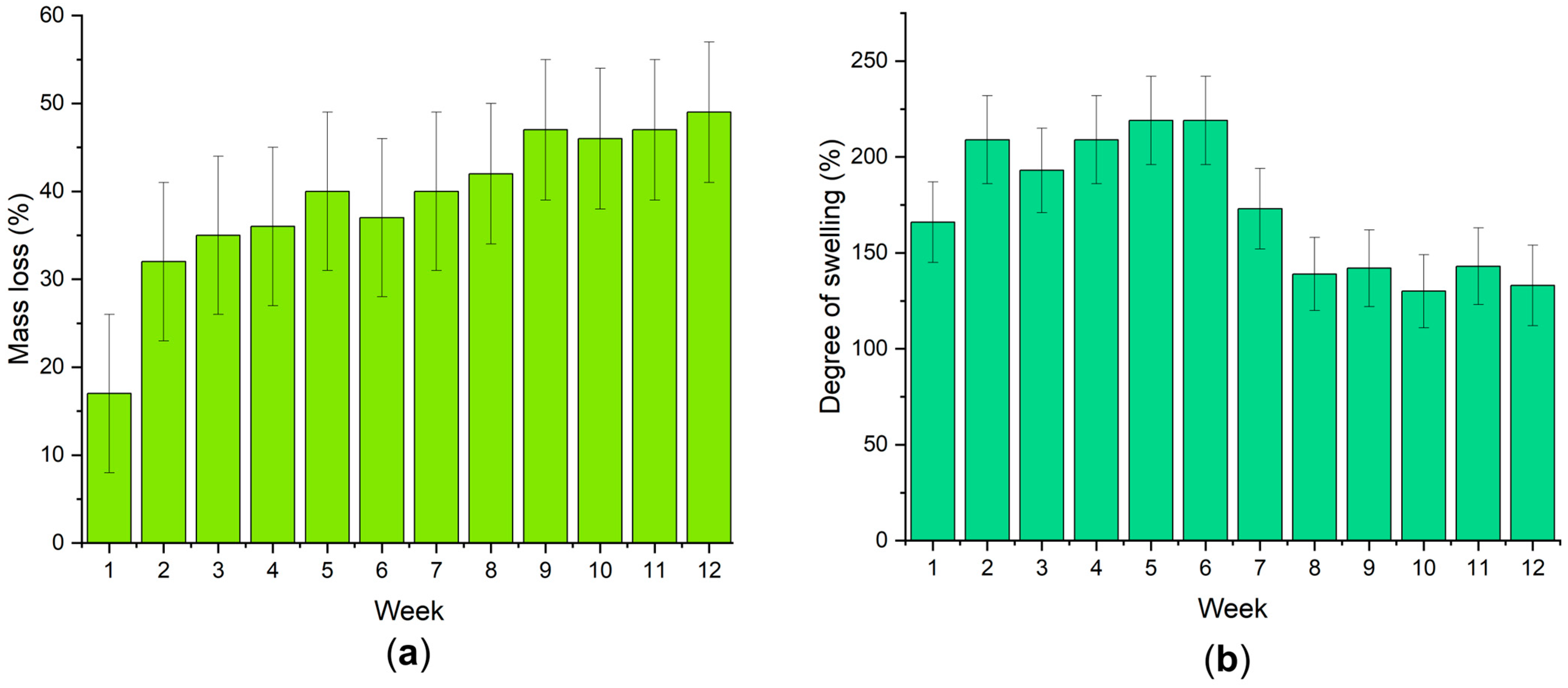

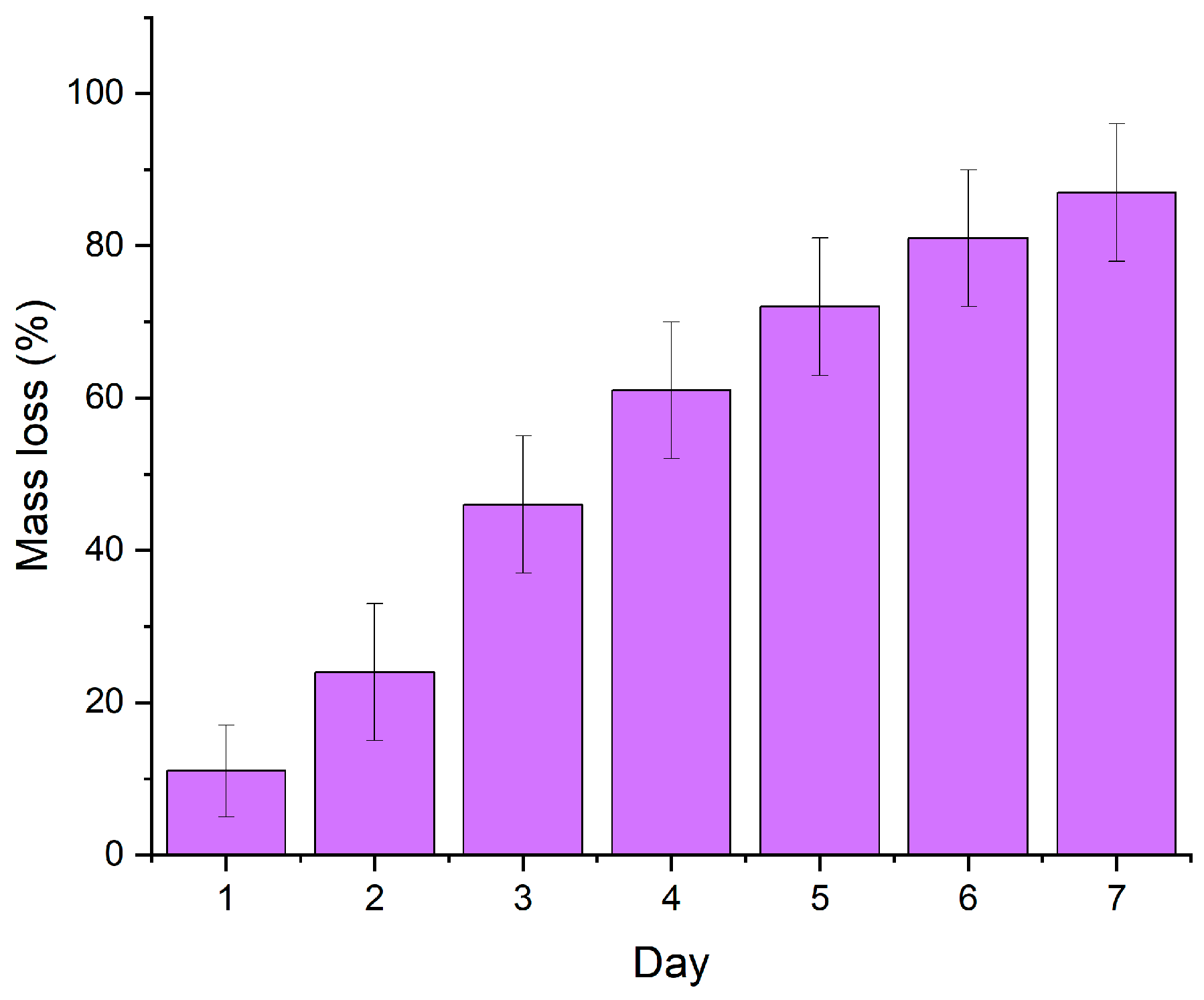

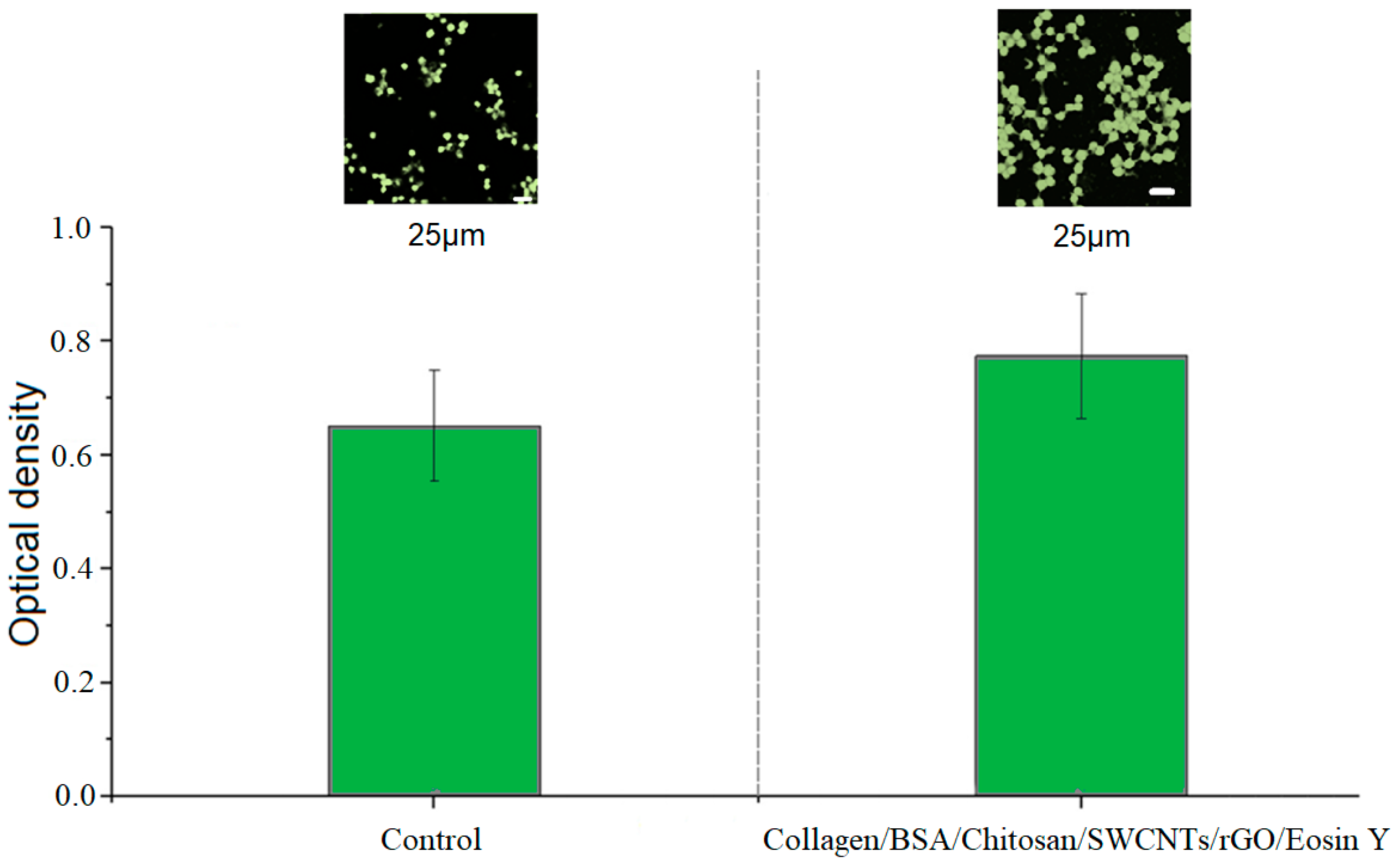

3.2. Biocompatibility

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SWCNTs | Single-wall carbon nanotubes |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| rGO | Reduced graphene oxide |

| Eosin Y | Eosin Yellow |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium |

| TD-DFT | Time-dependent density functional theory |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| MTT | Colorimetric assay for assessing cell metabolic activity |

References

- Staples, N.A.; Goding, J.A.; Gilmour, A.D.; Aristovich, K.Y.; Byrnes-Preston, P.; Holder, D.S.; Morley, J.W.; Lovell, N.H.; Chew, D.J.; Green, R.A. Conductive Hydrogel Electrodes for Delivery of Long-Term High Frequency Pulses. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Mi, G.; Shi, D.; Bassous, N.; Hickey, D.; Webster, T.J. Nanotechnology and Nanomaterials for Improving Neural Interfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1700905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelyev, M.S.; Kuksin, A.V.; Murashko, D.T.; Otsupko, E.P.; Kurilova, U.E.; Selishchev, S.V.; Gerasimenko, A.Y. Conductive Biocomposite Made by Two-Photon Polymerization of Hydrogels Based on BSA and Carbon Nanotubes with Eosin-Y. Gels 2024, 10, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Tian, L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, X.; Wu, L.; Fu, B.; Liu, X. Electrodeposition of Alginate with PEDOT/PSS Coated MWCNTs to Make an Interpenetrating Conducting Hydrogel for Neural Interface. Compos. Interfaces 2019, 26, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, A.Y.; Kuksin, A.V.; Shaman, Y.P.; Kitsyuk, E.P.; Fedorova, Y.O.; Murashko, D.T.; Shamanaev, A.A.; Eganova, E.M.; Sysa, A.V.; Savelyev, M.S.; et al. Hybrid Carbon Nanotubes—Graphene Nanostructures: Modeling, Formation, Characterization. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, F.; Mari, E.; Zicari, A.; Calcaterra, A.; Talamo, M.; Scioli, M.G.; Orlandi, A.; Mardente, S. Metal Free Graphene Oxide (GO) Nanosheets and Pristine-Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes (p-SWCNTs) Biocompatibility Investigation: A Comparative Study in Different Human Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, J.R.; Sousa, A.; Augusto, A.; Bartolo, P.J.; Granja, P.L. Electrospun Polycaprolactone (PCL) Degradation: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Polymers 2022, 14, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slepchenkov, M.M.; Barkov, P.V.; Glukhova, O.E. Hybrid Films Based on Bilayer Graphene and Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Simulation of Atomic Structure and Study of Electrically Conductive Properties. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Hall, W.; LaMantia, A.-S.; White, L. Neuroscience, 5th ed.; Sinauer Associates, Inc.: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0878936953. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, V.; Camelo, J.L.; Carri, N.G. Growth inhibition, morphological differentiation and stimulation of survival in neuronal cell type (Neuro-2a) treated with trophic molecules. Cell Biol. Int. 2014, 25, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dispersions | SWCNTs, g/L | rGO, g/L | BSA, g/L | Collagen, g/L | Chitosan, g/L | Eosin Y, g/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | – | 50.0 ± 1.0 | 25.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 5.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | – | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 50.0 ± 1.0 | 25.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 5.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 50.0 ± 1.0 | 25.0 ± 2.0 | 100.0 ± 5.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| Hydrogels | SWCNTs Concentration, g/L | rGO Concentration, g/L | Specific Electrical Conductivity, mS/cm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | – | 19 |

| 2 | – | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 17 |

| 3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Savelyev, M.; Kuksin, A.; Otsupko, E.; Suchkova, V.; Popovich, K.; Vasilevsky, P.; Kurilova, U.; Selishchev, S.; Gerasimenko, A. Application of Reduced Graphene Oxide in Biocompatible Composite for Improving Its Specific Electrical Conductivity. Eng. Proc. 2025, 117, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117011

Savelyev M, Kuksin A, Otsupko E, Suchkova V, Popovich K, Vasilevsky P, Kurilova U, Selishchev S, Gerasimenko A. Application of Reduced Graphene Oxide in Biocompatible Composite for Improving Its Specific Electrical Conductivity. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 117(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSavelyev, Mikhail, Artem Kuksin, Ekaterina Otsupko, Victoria Suchkova, Kristina Popovich, Pavel Vasilevsky, Ulyana Kurilova, Sergey Selishchev, and Alexander Gerasimenko. 2025. "Application of Reduced Graphene Oxide in Biocompatible Composite for Improving Its Specific Electrical Conductivity" Engineering Proceedings 117, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117011

APA StyleSavelyev, M., Kuksin, A., Otsupko, E., Suchkova, V., Popovich, K., Vasilevsky, P., Kurilova, U., Selishchev, S., & Gerasimenko, A. (2025). Application of Reduced Graphene Oxide in Biocompatible Composite for Improving Its Specific Electrical Conductivity. Engineering Proceedings, 117(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117011