A PSO-Driven Hyperparameter Optimization Approach for GRU-Based Traffic Flow Prediction †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

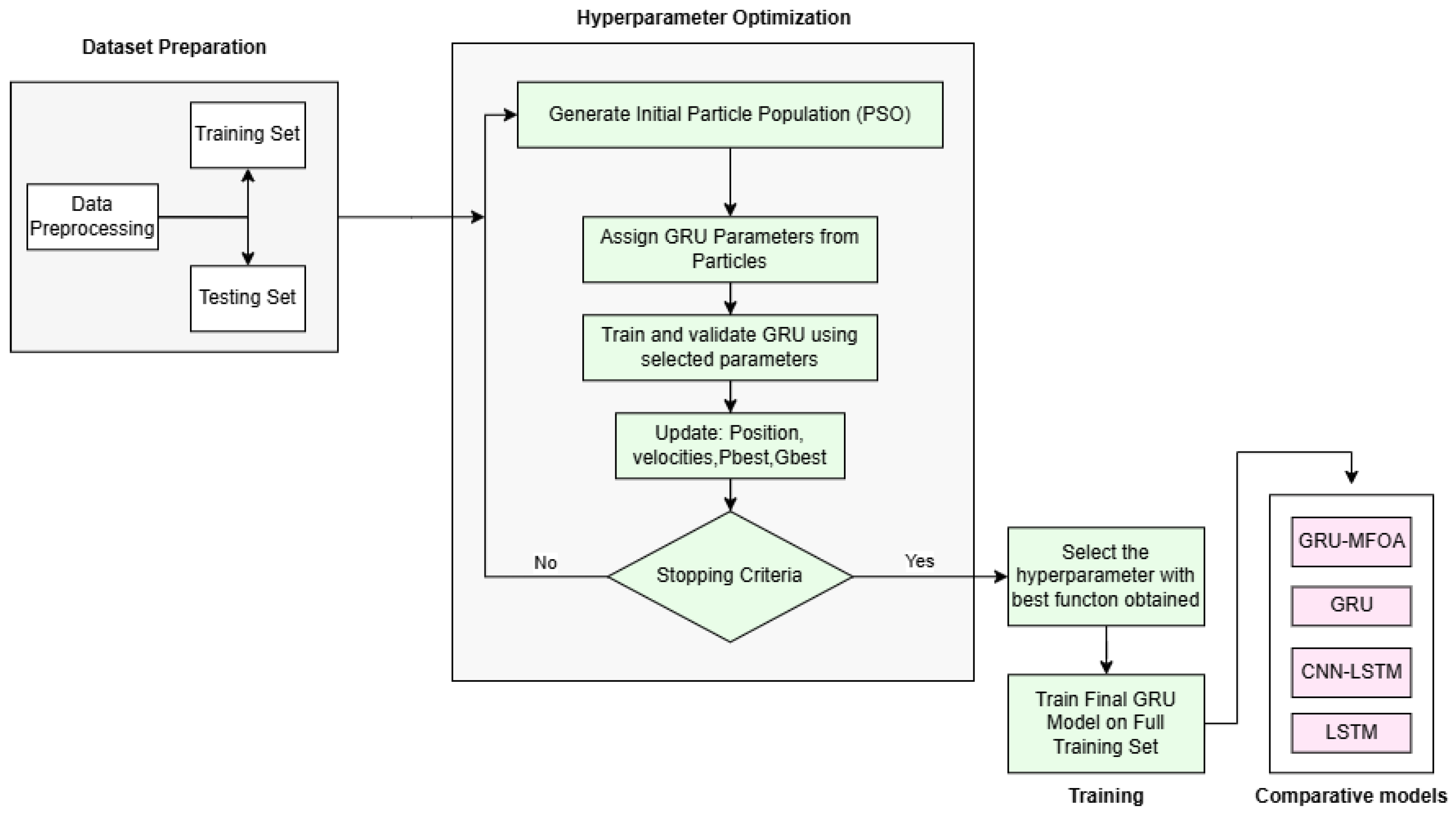

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Preprocessing

| Algorithm 1 PSO-GRU for traffic flow prediction |

|

3.2. Hyperparamteter

3.3. Problem Formulation

3.4. Training and Evaluation

4. Experiment

4.1. Data

4.2. Reference Models

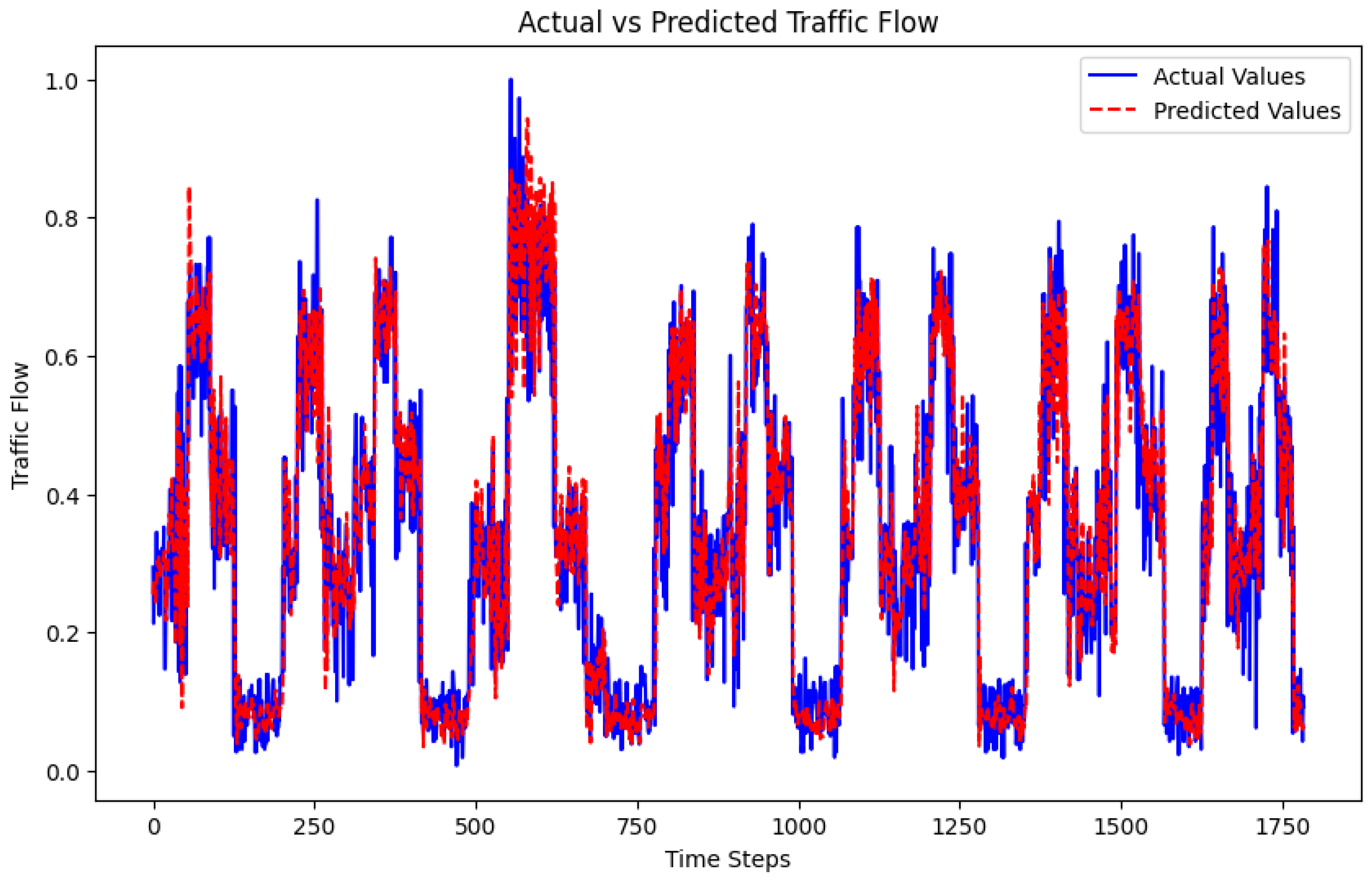

4.3. Result

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Das, S.; Tariq, A.; Santos, T.; Kantareddy, S.S.; Banerjee, I. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs): Architectures, training tricks, and introduction to influential research. Mach. Learn. Brain Disord. 2023, 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Stoean, C.; Zivkovic, M.; Bozovic, A.; Bacanin, N.; Strulak-Wójcikiewicz, R.; Antonijevic, M.; Stoean, R. Metaheuristic-based hyperparameter tuning for recurrent deep learning: Application to the prediction of solar energy generation. Axioms 2023, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q. Dynamic graph convolutional network with attention fusion for traffic flow prediction. In Proceedings of the ECAI 2023, Kraków, Poland, 30 September–4 October 2023; pp. 1633–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Chang, W.; Yin, C.; Xiao, P.; Li, K.; Tan, M. Attention-based spatial–temporal convolution gated recurrent unit for traffic flow forecasting. Entropy 2023, 25, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, P.; Li, B. GRU-and Transformer-based periodicity fusion network for traffic forecasting. Electronics 2023, 12, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, D. Global-aware enhanced spatial-temporal graph recurrent networks: A new framework for traffic flow prediction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04135. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Huang, J.; Shen, Q.; Shi, Q.; Shi, Z. A hybrid model integrating local and global spatial correlation for traffic prediction. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 2170–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, D. Spatiotemporal graph attention networks for urban traffic flow prediction. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE PIMRC, Virtual, 12–15 September 2022; pp. 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, W.; Cai, K.; Xiong, N.N. A short-term traffic flow prediction model based on an improved gate recurrent unit neural network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 16654–16665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, C.; Ye, W. Research on short-term traffic flow prediction based on KNN-GRU. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), Xiamen, China, 25–27 November 2022; pp. 1924–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Duan, Y.; Kang, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, F.-Y. Traffic flow prediction with big data: A deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 16, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bai, Y.; Yu, C.; Gu, Y.; Feng, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, R. A network traffic flow prediction with deep learning approach for large-scale metropolitan area network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/IFIP NOMS 2018, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh, Y.-L.; Yang, Y.-R. A short-term traffic speed prediction model based on LSTM networks. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2021, 19, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Chai, W.K.; Katos, V.; Walton, M. A joint temporal-spatial ensemble model for short-term traffic prediction. Neurocomputing 2021, 457, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ni, A.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, G.; Gao, L. Short-term traffic congestion prediction with Conv–BiLSTM considering spatio-temporal features. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 14, 1978–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.M.; Yiu, K.F.C.; Chan, K.Y.; Zhang, K. Conjoining congestion speed-cycle patterns and deep learning neural network for short-term traffic speed forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 138, 110154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Jiang, H.; Ji, N.; Yu, H. TBSM: A traffic burst-sensitive model for short-term prediction under special events. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 240, 108120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Afzal, M.K.; Ahmad, S.; Mostafa, A.M. Intelligent traffic flow prediction using optimized GRU model. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 100736–100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C. Traffic flow prediction based on depthwise separable convolution fusion network. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Kasamatsu, D. A traffic flow prediction method using road network data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE GCCE, Osaka, Japan, 10–13 October 2023; pp. 1192–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Naheliya, B.; Redhu, P.; Kumar, K. MFOA-Bi-LSTM: An Optimized Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Model for Short-Term Traffic Flow Prediction. Phys. A 2024, 634, 129448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmadha, S.; Vijayakumar, V. Spatio-Temporal Vehicle Traffic Flow Prediction Using Multivariate CNN and LSTM Model. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 81, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Su, K.; Ishibuchi, H.; Jin, Y. Synergistic Integration of Metaheuristics and Machine Learning: Latest Advances and Emerging Trends. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Parameter | Search Range | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| u | Number of GRU units | [32, 256] | Integer |

| Learning rate | [0.0001, 0.01] | Continuous | |

| Dropout rate | [0.1, 0.5] | Continuous | |

| b | Batch size | [16, 128] | Integer |

| L | Time-lag window size | Fixed = 10 | Integer |

| Model | MSE | MAE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRU (manual) | 0.0061 | 0.0568 | 0.0780 | 0.8762 |

| GRU-PSO | 0.0080 | 0.0665 | 0.0895 | 0.8371 |

| GRU-MFOA | 0.0089 | 0.0696 | 0.0945 | 0.8183 |

| LSTM | 0.0092 | 0.0711 | 0.0959 | 0.8130 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.0091 | 0.0706 | 0.0954 | 0.8150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Briki, I.; Ellaia, R.; Chentoufi, M.A. A PSO-Driven Hyperparameter Optimization Approach for GRU-Based Traffic Flow Prediction. Eng. Proc. 2025, 112, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112078

Briki I, Ellaia R, Chentoufi MA. A PSO-Driven Hyperparameter Optimization Approach for GRU-Based Traffic Flow Prediction. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 112(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112078

Chicago/Turabian StyleBriki, Imane, Rachid Ellaia, and Maryam Alami Chentoufi. 2025. "A PSO-Driven Hyperparameter Optimization Approach for GRU-Based Traffic Flow Prediction" Engineering Proceedings 112, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112078

APA StyleBriki, I., Ellaia, R., & Chentoufi, M. A. (2025). A PSO-Driven Hyperparameter Optimization Approach for GRU-Based Traffic Flow Prediction. Engineering Proceedings, 112(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025112078