Abstract

Today, the right to easy access to medical care for all citizens is one of the universal rights promoted by the WHO to achieve the health goals of sustainable development. Furthermore, an intelligent reevaluation of hospital management is becoming an absolute necessity in light of the pressure that healthcare and public health establishments worldwide face. A management based on the capitalization and exploitation of vast quantities of knowledge. In the 21st century, medicine has already moved to the “in silico” phase, where healthcare professionals must use knowledge bases to make clinical decisions. Indeed, knowledge gains greater value when it’s actively engaged with through dynamic knowledge bases. There is a plethora of research on hospital management, but few studies have approached it from the angle of informational intelligence governed by knowledge management. In this article, we adopt a positivist posture, using deductive logic and the Delphi method based on expert opinion and consensus. We aim to approach hospital management from an informational intelligence perspective, inspired by knowledge representation systems and the object approach. We present an initial vision of the intelligent hospital management model, showing its strengths in relation to its predecessors, as well as its potential uses.

1. Introduction

An efficient health system is, undoubtedly, a system in which everyone has the right to health services with the required quality it is also a system that respects human dignity, and in which each individual in society can recover his or her health needs without incurring financial or administrative difficulties, a system that has the resources and ensures an equitable distribution of health care within its population: these are, according to the WHO (World Health Organization), some of the elements that mark efficient health systems [1].

The health care system is constantly under pressure, as it is subjected to the heaviness of the health care bill with all its constraining imperatives, it must also orchestrate between satisfying the increased and evolving needs of the population as well as rationalizing its resources to guarantee a potential equilibrium challenged by an economic period marked by multiple difficulties. These various difficulties of a demographic nature, the lack of necessary infrastructures, as well as the lack of competencies and quality of the care services offered within the hospital structures, push the obligation to rethink the mode of hospital management to which these health structures are already subjected. This is to carry out a radical reorganization of the modes of hospital management. Indeed, the reflection on hospital management acquires its legitimacy from the very nature, which is rather convoluted, of these establishments. The hospital, as a complex organization, shelters varied services and ensures the satisfaction of the heterogeneous needs of its users while mobilizing its resources. We aim to highlight the emergence of a new managerial model that establishes a strong bijection, at a lower cost, between the immaterial world and the physical world.

We will try to explain how the adequate deployment of Knowledge Management (KM) within hospital structures can stimulate a dynamic of Informational Intelligence (II), contributing to new governance of these instances against the already adopted managerial models.

We will explain the effects of KM on the implementation of a new hospital management model, while rigorously explaining the concepts involved.

We present the different managerial styles governing the hospital scene. We present our proposed new managerial model, linking it to its predecessors.

We clarify the effect of knowledge capitalization in improving the care provided by healthcare professionals in today’s “in silico” phase of medicine. A phase in which major clinical experiments are carried out virtually, using computer simulation tools, and in which the use of multiple knowledge bases is becoming more evident. Such Medicine that is more predictive, more preventive, and more personalized.

2. Hospital Management Models in Light of Public Health Systems

2.1. Porter’s Value Chain Approach

Value-based management is inspired by Porter’s value chain model. Developed in 1990, this type of management has been enriched over time and has added new dimensions to its previous versions, such as competitive advantage through costs and differentiation, performance for the customer linked to the satisfaction of a need, economic performance for the investor, and finally, the performance of the supplier in terms of shared quality benefits [2]. This process can be summarized in three types of relationships where stakeholders interact carefully: the impact of the environment on the performance of value-producing activities, the interaction of activities involving cause and effect relationships, and the flow of value from the organization to the beneficiary parties. To put this model into practice and identify the influence of the hospital environment on the creation of value, it makes sense to theoretically approach the value produced by these hospital structures. To this end, two criteria are adopted: a quantitative criterion linked to hospital capacity in terms of the number of beds and specialties covered, and a qualitative criterion relating to the missions assumed by these hospital structures. In Nobre’s view, in the case of healthcare, the analysis of value production in public hospitals is subject to three theoretical perspectives [3]: functional analysis, temporal analysis, and analysis of the medical activity. For temporal analysis, the nature of the hospital act incorporates the time horizon as a determining parameter, especially for preventive acts related to future pathologies whose valuation is uncertain because the gain, or value, is only expected when the pathology is avoided. As for curative acts, they concern existing pathologies with a certain value. As for the analysis of medical activity, Nobre specifies three components of the medical activity: diagnostic activities, patient relationships, and the organizational component.

2.2. The New Public Management Approach

The NPM concept emerged in the 1960s and 1970s with the aim of adapting business management techniques to the public domain, while recognizing the specific characteristics and constraints of public administration. Although the nature of the value they create is different, the two sectors come together in the manufacturing of goods and services. While the value expected from the business world relates to the return on capital employed, the public domain seeks a value linked to the satisfaction of the general interest, with a slight responsibility towards the financial constraint resulting from the permanent financial support of the State and local authorities. In addition, the contrast and difficulty of transposing private-sector logic can also be explained by two fundamental notions: path dependence and hybridization.

In the healthcare system, path dependency is a brake on institutional change or the dismantling of services within hospital structures. So hence, any change in institutional arrangements is often dependent on legacies of the past [4]. Hybridization is understood as a mode of regulation, a set of organizational arrangements that leads to strong coordination between autonomous actors in the healthcare sector.

One of the strengths of this managerial model in the healthcare sector is its ability to absorb political decisions and separate them from managerial actions. Finally, we can synthesize the NMP around three constituent principles: managerialism, to the extent of seeking better cost control, accountability, and contractualization [5].

2.3. Quality Management Approach

The transposition of the concept of quality within the hospital structures puts all the actors of the health sector at the center of interest in the system to ensure their permanent satisfaction. However, the fragmentation of hospital activities with the multiplicity and heterogeneity of the actors in the sector generates organizational difficulties within hospitals whose current activity is in full recrudescence. This situation pushes towards more commodification and commercialization of health care, thus calling into question the eligibility of the sector, which has made the search for quality and qualification of hospital structures relatively delicate, especially with standards and certification procedures that are often subject to frequent updates without any room for autonomy for the actors. Also, the quality of the health service is often approached according to the therapeutic service itself (curative or preventive) in terms of sustainability, reliability, and efficiency this can be associated with the conquest of excellence through the idea of continuous improvement as part of the strategic axes of the health institution [6].

The quality management approach in hospitals is very similar to the standardized approach of ISO 9001, which is based on a real systemic vision of the organization. The particularity of this approach resides in the staging of a variety of criteria ensuring the performance of the hospital which are articulated around four major dimensions [2]: strategic, to the result-related, economic, and ethical.

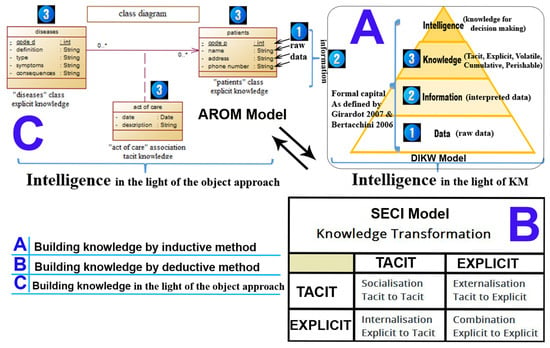

3. Informational Intelligence in the Light of Knowledge Management and OBKRS

According to Ackoff’s model, knowledge is constructed from a set of information that revolves around a meaning. Information is a set of homogeneous elementary data [7]. The information in itself remains useless and presents only a relative interest; its real value resides in its role of constitution and enrichment of the knowledge. So knowledge encompasses a body of information sharing a common structure accepted by the human mind. Knowledge also has great value because it capitalizes on the information that comes into play, thus constituting a considerable utility in guiding strategic decision-making [8]. It should be remembered that the majority of organizations analyze the information available to them to capitalize on it in the form of knowledge for strategic use. In their INTDATA informational intelligence model [9], Ibrahimi et al. adopt three methods of knowledge capitalization (as shown in Figure 1):

- Deductive method, which builds knowledge on the basis of Ackoff’s DIKW [7] pyramid.

- Inductive method, which builds knowledge on the basis of the SECI transformation dynamics of tacit and explicit knowledge [10].

- Capitalization method based on the object approach [11] (pp. 21–59).

Knowledge management is the effective understanding of the information sphere handled within an organization so that it can be rigorously exploited. This ensures an intelligent organizational climate at all levels. It’s a process based on the exchange and communication of knowledge, to consolidate the engineering of information systems within organizations. Knowledge management can be viewed through a managerial lens, where knowledge is regarded as a strategic resource that underpins decision-making and shapes strategic direction [12]. A strong link exists between the pursuit of informational intelligence and the process of knowledge capitalization, which acts as a critical enabler. However, the success of this capitalization largely hinges on the precision and clarity of knowledge representation. The concept of intelligence is inherently connected to the capacity to make well-informed choices based on the acquisition of pertinent information.

This highlights the increasing significance of proper knowledge representation in facilitating both knowledge capitalization and the pursuit of intelligence.

Object-oriented knowledge representation systems (OKRS) are based on frame-based languages [13] and description logics [14], while exploiting the expressive power of conceptual graphs and the instantiation mechanisms characteristic of semantic networks. These systems stand out for their efficiency in intelligent knowledge management. Based on the object-oriented paradigm [15,16], they take advantage of various inference mechanisms such as classification, identity, polymorphism, and inheritance, giving them robustness and flexibility. In this context, Blaha and Rumbaugh [11] (pp. 21–59) conceive knowledge as a set of object classes representing similar entities. A class thus constitutes a common reference structure for a group of objects sharing the same attributes, behaviors, constraints, and semantic meanings. For example, the “Diseases” class groups together all knowledge relating to medical conditions, facilitating the establishment of links with the patient’s class. Page et al. propose the model AROM (Allier Relations et Objets pour déliser) for knowledge representation, based on an approach inspired by UML modeling techniques, recognized for its dynamic expressiveness [17]. Their approach emphasizes the central role of associations between classes, giving them an importance equivalent to that of the classes themselves, thus underlining the semantic richness of relationships. Within the framework of this model, knowledge representation diagrams give the class a new status as a central concept, serving to instantiate information-carrying objects. Each object is made up of attributes, representing elementary data, enabling knowledge to be finely and rigorously structured. Figure 1 shows a representation of the knowledge base taking into account the three knowledge capitalization models: The “disease” class contains the list of records (information) containing the different existing diseases, each one is characterized by the five mentioned data. The association “Act of care” is tacit knowledge that requires the preliminary knowledge of the patient and the disease; it also contains records or information concerning the duration of the care and the description of the act of care.

Figure 1.

Representation of the knowledge base.

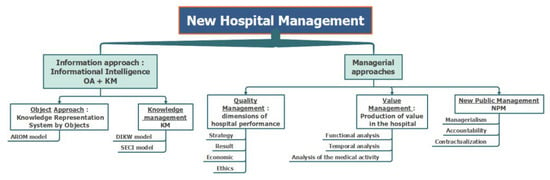

4. New Hospital Management Inspired by Informational Intelligence

The vocation of the knowledge representation system by objects is multiple; on one hand, it guarantees a modeling language with a generic aim for any application domain, in particular, that of health. On the other hand, it facilitates the massive exploitation of knowledge by taking into account their mode of conception, which starts from the raw data constituting the core of the information arriving at the knowledge and then at the intelligence and the assembly of strategies. Our proposed knowledge capitalization model (Figure 1) is based on three capitalization methods (inductive, deductive, and object approach), which represent tacit and explicit knowledge. Object modeling is based on the concept of the object and distinguishes the class object (the knowledge) from the instance objects (the information) [18]. In this class-instance vision, where knowledge is structured around classes, core modeling principles include classification, inheritance, specialization, and polymorphism. The field of health is so rich in actors and knowledge coming from internal and external sources of hospital structures. Knowledge from the internal environment, which is of a medical type and others manipulated by all health actors, in tacit or explicit form with biomedical, clinical, epidemiological, or socio-behavioral aspects, can also come from the external environment of hospitals about the patient, suppliers, and other health actors. This cognitive richness is useful for curative and preventive care activities, as well as for clinical decision-making and care planning. It also helps to create a new hospital management style. Abidi, for his part, specified eight types of knowledge that contribute to clinical decision-making and care planning, of which seven are directly linked to the act of care [19]. With this cognitive arsenal and health registry, all hospital players will be equipped with the knowledge they need to make the right decisions. The final goal is to establish a hospital management system based on intelligent data transformation. A transformation that concatenates data to form meaningful information. This information takes the form of a record containing several raw data items, and in turn forms the solid core of tacit or explicit knowledge. Figure 2 illustrates the building blocks of the new hospital management approach, which takes into account other hospital management models as well as informational intelligence:

Figure 2.

New hospital management in the light of II and managerial approaches.

Indeed, on the one hand, this new hospital management model adopts the major managerial features of the first three models mentioned, and on the other, it relies heavily on the positive spin-offs of knowledge management. It enables the hospital to preserve its cognitive heritage in terms of accumulated experience and know-how. Knowin that this heritage is deteriorating with the turnover and retirement of experts.

This new hospital management model is a synthesis of the three DIKW, SECI, and AROM models. It incorporates both inductive and deductive methods, inspired by the first two models, to capitalize on knowledge, starting from initial data and arriving at the main transformation dynamics of the SECI model developed by Nonaka, the “founding father of Knowledge”. The role of the AROM model is to represent this knowledge in the form of class diagrams, to give it a dynamic aspect, and to be able to represent non-formal tacit knowledge.

5. Comparison with Other Hospital Management Models

- The New Public Management (NPM), in addition to its anomalies related to path dependency and hybridization, has also marked negative effects on occupational health; these effects weigh, in fact, on public employees through the imposition of new requirements [20]. The NPM, as a set of processes of finalization, organization, and control of public hospital structures, aims through its seven principles [21] to steer and develop the evolution of these structures, but it induces a kind of relational harshness [22] and increases incivilities in interpersonal relations at the level of hospital services [23]. Healthcare services are already heterogeneous in terms of the profiles and nature of the tasks performed by their personnel, as well as the multiplicity of stakeholders. The rise of these incivilities within healthcare institutions has an impact on relations with users, and the deployment of the NPM has created a kind of rigidity and bureaucracy that prevents the administrative organization from playing its role correctly.

- As for Porter’s value-chain management, several studies today point to a real difficulty in defining the production of value in hospitals, given the multiplicity of actors involved in the health scene [3]. This managerial model was always influenced by the economic context and changes in medical practices.

- For quality management, its limitations are due, on the one hand, to the quality standard itself, which can often be perfected on an international scale. Its limitations are also due to the fragmentation of activities and the need for high levels of specialization within healthcare departments, as well as the multiplicity of players involved. In addition to these obstacles, there is a growing need for qualified and motivated healthcare personnel, and the population’s health needs are constantly changing. All these factors combined to depress the quality of care services in public hospitals. The healthcare sector is an ideal field of application for knowledge management, since all kinds of medical activity are imperatively governed to a large extent by the exploitation of knowledge. The examples are numerous: knowledge of the efficacy of new drugs, professional training for healthcare executives, patient medical records, and online patient advice services are just a few of the many examples [24]. The final goal behind the deployment of knowledge management, in the public domain in general and in public health in particular, lies in its ability to absorb all concerns and maintain an overall perspective of public authorities on service delivery and policy development in general [25]. Unlike other hospital management models, our proposed approach is capable of capturing both explicit and tacit knowledge. Its dynamic nature stems from its foundation in UML and object-oriented principles. In this model, the class diagram functions as a dynamic knowledge grid, continually updated by another diagram linked to the multiple use cases, which describes the requirements for system operation.

6. Conclusions

This article proposes a novel conceptual framework for understanding the hospital management model. This vision is predicated on three knowledge construction models (DIKW, SECI, and AROM). This managerial model is predicated on the capitalization and representation of knowledge. The implementation of these deductive, inductive, and object-oriented capitalization mechanisms in medical activities provides healthcare professionals with enhanced precision in their clinical decision-making processes. This phenomenon is particularly evident when considering the historical progression of medicine throughout the 19th century. During this era, medical practice was characterized by the “in vivo” phase, which entailed the observation and treatment of bodily symptoms. However, with the advent of the 20th century, a paradigm shift occurred, marking the transition to the “in vitro” phase. This new era was marked by the development of pharmaceuticals and the treatment of disease. In the contemporary era, the advent of the “in silico” phase (employing computer simulation tools) has ushered in a paradigm shift within the medical field, characterized by heightened predictive capabilities, augmented preventive measures, enhanced patient participation, and a more customized approach to healthcare. In the contemporary healthcare environment, professionals require a substantial degree of cognitive complexity to effectively navigate and synthesize the vast repositories of medical knowledge. This ability is pivotal in enabling them to formulate independent judgments and decisions that contribute to optimal patient care. In such contexts, the process of knowledge capitalization is relegated to a low-level activity. This proves that governing a hospital’s health info-sphere with informational intelligence practices in terms of knowledge acquisition, representation, and management greatly facilitates dynamic clinical decision-making. These practices also help to centralize and unify the creation, use, and maintenance of clinical knowledge, offering more opportunities than the simple use of digital tools. This is obvious, as these practices call upon the healthcare professional’s expertise and accumulated experience, generally tacit, as well as his or her interpretative capacities, which have no limits. This knowledge is highly valuable, as it determines a high level of expertise, know-how, and the way actors behave and act, and its transformation into formal explicit knowledge through the SECI model’s externalization mechanism is a major issue and challenge for the scientific community, as it will help future generations to deploy this valuable heritage.

Finally, and on the basis of the analyses carried out, we reiterate the assertion that everything that matters within an organization is immaterial. We would also add, at this level, that the proper and pertinent valorization of this intangible capital imperatively requires the introduction of practices linked to the mastery of information intelligence skills, which will help to make healthcare establishments more efficient. A new field of research is emerging, one that can be called “beyond artificial intelligence”. This is informational intelligence, or the capitalization of knowledge in all its forms, after years of study devoted solely to the visualization of information, which constitutes only a tiny part of knowledge. Such knowledge is challenging to control and often characterized by irregular or fragmented availability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.; methodology, M.I.; writing, M.I.; supervision, M.I. and B.D.; review, B.D.; editing, M.I.; visualization, M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the associated data are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Faire des Choix Justes Pour une Couverture Sanitaire Universelle: Rapport Final du Groupe Consultatif de l’OMS sur la Couverture Sanitaire Universelle et Equitable; OMS: Genève, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sebai, J. L’évaluation de la performance dans le système de soins. Que disent les théories? Santé Publique 2015, 27, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobre, T. Management de la valeur et pouvoirs dans l’hôpital. Financ. Contrôle Strat. 1998, 1, 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Demailly, L.; Giuliani, F.; Maroy, C. Le changement institutionnel: Processus et acteurs. Sociologies 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abord de Chatillon, E.; Desmarais, C. Le nouveau management public est-il pathogène? Manag. Int./Int. Manag./Gestiòn Int. 2012, 16, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayo-Villeneuve, S. Vers un Modèle Intégrateur des Démarches Qualité à L’hôpital: L’apport des Outils de Gestion. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lorraine, Nancy, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L. From data to wisdom. J. Appl. Syst. Anal. 1989, 16, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Queyras, J. L’intelligence Économique Territoriale dans un Centre D’information du Service Public: Application à la Cooperation Scientifique et Universitaire Franco-Brésilienne. Ph.D. Thesis, Université du Sud Toulon-Var, Toulon, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahimi, M.; Debbagh, B. Introduction to the New Data Intelligence Model (INTDATA). In Communication and Information Tech-Nologies Through the Lens of Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge Creating Company; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Blaha, M.; Rumbaugh, J. Object-Oriented Modeling and Design with UML; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grundstein, M.; Rosenthal-Sabroux, C. A sociotechnical approach of knowledge management within the enterprise: The MGKME model. In Proceedings of the 11th World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–11 July 2007; pp. 284–289. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. A Framework for Representing Knowledge. In The Psychology of Computer Vision; Winston, P., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 211–277. [Google Scholar]

- Baader, F.; Calvanese, D.; McGuinness, D.L.; Patel-Schneider, P.F.; Nardi, D. The Description Logic Handbook: Theory, Implementation and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ducournau, R.; Euzenat, J.; Masini, G.; Napoli, A. Langages et Modèles à Objets: État des Recherches et Perspectives; INRIA: Paris, France, 1998; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli, A.; Carré, B.; Ducournau, R.; Euzenat, J.; Rechenmann, F. Objets et représentation, un couple en devenir. Obj. Logiciels Bases Données Réseaux 2004, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; Gensel, J.; Capponi, C.; Bruley, C.; Genoud, P.; Ziébelin, D. Représentation de connaissances au moyen de classes et d’associations: Le système AROM. In Proceedings of the Actes des Journées Langages et Modèles à Objets (LMO 2000), Mont Saint-Hilaire, QC, Canada, 25–28 January 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gensel, J. Représentation de Connaissances par Objets pour la Modélisation et L’adaptation D’informations Multimédias et Spatio-Temporelles. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Joseph Fourier (Grenoble 1), Grenoble, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abidi, S.S.R. Healthcare knowledge management: The art of the possible. In Proceedings of the AIME Workshop on Knowledge Management for Health Care Procedures, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7 July 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Noblet, A.J.; McWilliams, J.; Teo, S.T.; Rodwell, J.J. Work characteristics and employee outcomes in local government. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 17, 1804–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. The ‘new public management’ in the 1980s: Variations on a theme. Account. Organ. Soc. 1995, 20, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, T. New public management in public sector organizations: The dark sides of managerialistic ‘enlightenment’. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, M.H. Writing What’s Relevant: Workplace Incivility in Public Administration-A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing. Adm. Theory Prax. 2006, 28, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, D.; Powell, J.; Conville, P.; Martinez-Solano, L. Managing knowledge in the healthcare sector. A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Dumay, J.; Garlatti, A. Public sector knowledge management: A structured literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 530–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).