1. Introduction

The exponential rise of wireless technologies and the Internet of Things (IoT) has led to a significant increase in the number of connected devices deployed across diverse environments, from smart cities to wearable and implantable systems. These devices, often powered by compact sensors, require energy sources that are autonomous, maintenance-free, and environmentally sustainable, posing limitations for traditional batteries due to their short lifespan and ecological footprint.

In response, a variety of ambient energy-harvesting techniques have been explored over the past decade to power low-energy devices, such as wireless sensors (WS) and implantable medical devices (IMDs). Energy harvesting offers a continuous power supply for sensors by utilizing various ambient sources, such as solar, thermal, piezoelectric, and radio frequency (RF) energy, each with distinct characteristics [

1], using appropriate energy converters. In this context, radio frequency energy harvesting (RFEH) has emerged as a promising approach, enabling the conversion of electromagnetic waves into usable electrical energy [

2]. Unlike other sources, RF energy is continuously available in both indoor and outdoor environments. Despite recent advances in antenna design, impedance matching circuits (IMCs), and RF-to-DC rectifiers, RFEH systems are still limited by the low power density of ambient RF signals, fluctuating signal conditions, miniaturization constraints, and the complexity of extracting usable energy from variable RF sources.

This systematic literature review (SLR) provides a comprehensive and up-to-date synthesis of RFEH technologies. It focuses on three essential subsystems: the receiving antenna (RA), the impedance matching circuit (IMC), and the rectifier. Based on the analysis of 25 selected articles published between 2020 and 2025, this study identifies core design strategies, highlights key technical challenges, and outlines research directions toward the development of reliable, compact, and energy autonomous electronic systems.

2. Methodology

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA methodology (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), ensuring a rigorous, transparent, and reproducible approach. The literature search was performed on the Scopus database using the keywords “RF harvesting”, “antenna”, and “sensors”. The search was restricted to publications from 2020 to 2025 and limited to conference papers, journal articles, and book chapters to ensure academic relevance and quality. An initial search yielded 279 articles. After the removal of duplicates (15 articles), 264 unique studies remained. A first screening based on titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 188 articles that were either irrelevant or did not meet the eligibility criteria. Among the remaining 76 articles, 10 could not be retrieved due to access restrictions, resulting in 66 full-text articles. An additional filtering step was applied based on the median number of citations per year (excluding 2025), which led to the exclusion of 41 articles with low citation impact.

In the end, 25 studies were selected for in-depth analysis (as illustrated in

Figure 1). These works focus on the design and performance of radio frequency energy-harvesting (RFEH) system components. This structured methodological process ensures a scientifically robust and relevant selection, thereby supporting the quality and reliability of the findings presented in this review.

3. Radio Frequency Energy Harvesting (RFEH)

RFEH systems enable the conversion of ambient electromagnetic energy into electrical power, offering a sustainable alternative to conventional batteries for low-power devices.

Figure 2 illustrates the general operating principle of an ambient RF energy-harvesting system, where the colored lines represent the propagation of electromagnetic waves radiated from surrounding sources toward the receiving antenna, which captures and converts them into usable electrical energy. The environment contains multiple RF sources that collectively form an exploitable energy reservoir, though their non-directional nature often leads to low received power levels [

3]. RFEH approaches are generally classified into two types: ambient energy harvesting, which captures existing RF signals from existing infrastructure such as cellular base stations, Wi-Fi routers, FM/TV stations, dedicated transmitters, and other sources [

2], and dedicated energy harvesting (or Wireless Power Transfer, WPT), which uses purposefully generated RF signals to provide energy to remote or embedded devices [

4]. While differing in source and implementation, both approaches are based on the same principle: converting electromagnetic waves into usable electrical energy. RFEH shows strong potential for powering IoT devices, wireless sensors, wearable systems, and remote monitoring applications in a self-sustaining and maintenance-free manner.

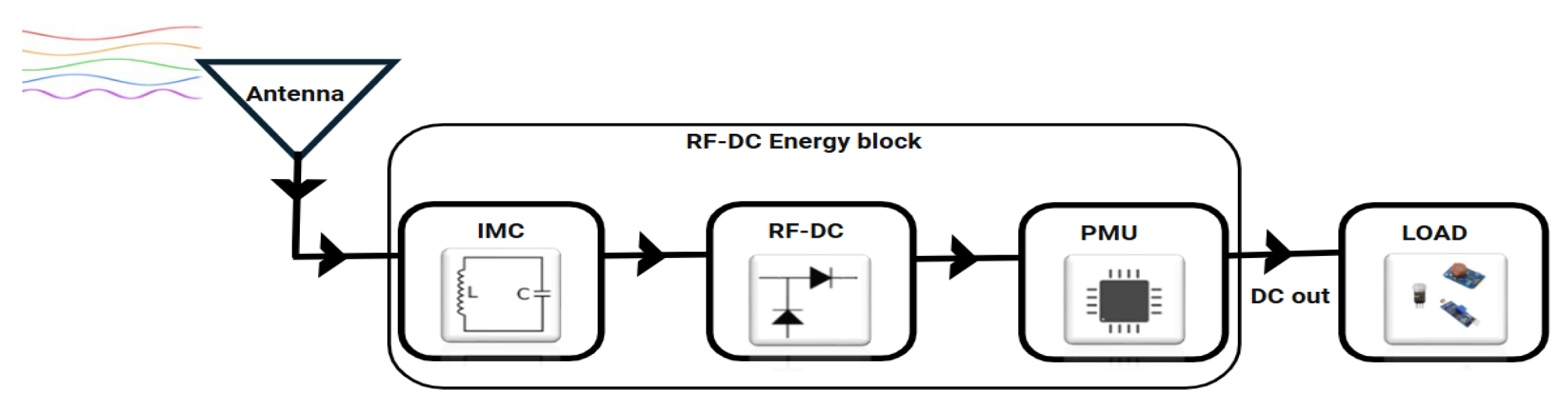

Figure 3 presents the detailed functional architecture of an RFEH system, which typically consists of a receiving antenna (RA), an impedance matching circuit (IMC), and an RF-to-DC rectifier. The RA captures ambient RF energy and delivers it to the IMC, which optimizes energy transfer by matching impedances with the rectifier. The rectification stage then converts the alternating RF signal into a stable DC output suitable for powering electronic loads [

5]. Some systems also include a power management unit (PMU) to regulate and stabilize the output [

1,

6], although PMU integration may introduce additional complexity and power losses. The overall performance of an RFEH system is strongly influenced by the selection and interaction of its components. Antenna design must be adapted to the operating frequency and application context, while the rectifier architecture plays a critical role in determining energy-conversion efficiency. The combination of these factors directly impacts the feasibility of RFEH systems in real-world deployments.

Recent research increasingly focuses on the joint optimization of antenna design, impedance matching, and rectification, emphasizing miniaturization and energy efficiency to meet the demands of next-generation autonomous systems.

3.1. Receiving Antenna for RFEH

Among the key components of an RFEH system, the RA plays a pivotal role in capturing electromagnetic energy. Its performance directly influences the system’s overall power conversion efficiency. The selection of a RA critically influences the performance of RFEH systems. High-gain antennas efficiently capture ambient RF signals, especially from low-power sources. Choosing an RA depends on environmental RF availability, target applications, and size constraints. The literature presents diverse antenna designs tailored for RFEH.

Table 1 summarizes key antenna characteristics, such as frequency, gain, dimensions, and substrates, helping in the evaluation of trade-offs between gain, polarization, miniaturization, and frequency coverage.

Various antenna types have been explored in the literature for use in RFEH, each offering specific advantages depending on the application. These include dipole [

4,

6], planar [

7,

8,

9], textile [

10], and flexible antennas [

11]. For instance, flexible or textile antennas, though limited by substrate-induced radiation losses, offer benefits in mechanical flexibility and seamless integration into garments or medical antennas. Patch antennas are the most widely adopted due to their compact size, low cost, simplicity, and easy integration with electronic circuits [

2,

5,

10,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Their reliable performance in terms of gain, polarization control, and frequency adaptability makes them particularly suitable for RF energy capture.

As antenna selection is often driven by the characteristics of the targeted frequency bands, it is essential to examine the most commonly used spectral ranges in RFEH systems. The 2.4 to 2.5 GHz band is widely adopted due to its high density of available RF signals from Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and ISM applications [

5,

8,

9,

10,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

19,

22,

23]. Other bands, such as RFID [

17], 4G/5G [

7], FM/TV [

6], or GSM [

16], are selected based on signal availability and application-specific constraints. Narrowband antennas are well suited for scenarios where the RF source is known and fixed; however, they limit the simultaneous harvesting of multiple ambient signals, which can be a disadvantage in dynamic or multi-source environments. To overcome this limitation, wideband or ultra-wideband (UWB) antennas are utilized. For example, a compact dual-port 2 × 1 UWB MIMO antenna covers 2.3 to 21.7 GHz with high gains (up to 10.29 dBi), excellent efficiency (99% at 13.5 GHz), and a compact size (39 × 30 mm

2), using Rogers RT 5880 as a substrate due to its excellent dielectric properties (

,

); while FR4 is commonly used in patch antenna designs, the superior dielectric properties of Rogers RT 5880 offer significant performance advantages, particularly at higher frequencies [

15]. Multiband antennas also enable energy harvesting across multiple frequency bands simultaneously. For instance, the designs proposed in [

8,

23] operate over several frequency ranges (0.85, 1.81, 2.18, 2.40 GHz) and (1.8, 2.1, 2.4, 2.65, 3.5 GHz), respectively, achieving moderate gain values of 3.95–4.82 dBi and 1.59–3.46 dBi. These results illustrate the typical trade-offs associated with multiband antenna designs, where supporting multiple frequencies often comes at the cost of reduced gain or increased design complexity. Additionally ref. [

23] features left-hand and right-hand circular polarization (LHCP and RHCP), which enhances signal reception regardless of the antenna’s orientation. This example also demonstrates how specific slot patterns and circular geometries contribute to the generation of circular polarization (CP). Although geometrically more complex, CP is especially preferred for its strong resistance to polarization mismatch and its ability to mitigate multipath fading [

5], making it particularly well suited for wearable applications where antenna orientation varies unpredictably.

Miniaturized antennas, essential for integration into compact or implantable devices, often involve performance trade-offs. In particular, reducing the antenna size can significantly compromise its radiation efficiency and overall energy-harvesting capability, frequently resulting in a noticeable reduction in antenna gain. For example, the CPW-fed monopole antenna reported in ref. [

13], with dimensions of only 24.9 mm × 8.6 mm and operating at 2.45 GHz, achieves a relatively low gain of 0.8 dBi, primarily due to the constraints imposed by its highly miniaturized structure. Recent innovations involving metastructures (e.g., AMC, EBG, metalenses), slot configurations, and advanced dielectrics have significantly enhanced antenna performance. For instance, combining AMC and slot techniques achieves RHCP, high gains (8–9.5 dBi), and maintains compact dimensions (50 mm × 50 mm) [

9]. Another design, integrating a metalens with an AMC antenna has been shown to boost gain from 8 to 19 dBi [

21]. Despite the inherent trade-offs, these advanced techniques offer an effective balance between gain, polarization, miniaturization, and frequency coverage.

Selecting the appropriate antenna requires balancing performance indicators (gain, bandwidth, and polarization) with practical constraints (size, orientation, and integration). High gain often implies larger size, limiting use in wearable or implantable devices, while circular polarization improves robustness but adds complexity. For low-power or implantable applications, compact metasurface antennas are preferred. Textile and flexible antennas offer mechanical adaptability but face efficiency losses. In contrast, wideband or UWB suit dynamic IoT nodes exposed to multiple RF sources, despite lower gain. Each design must align with the target application’s needs and limitations.

3.2. Impedance Matching Circuit for RFEH

In RF-energy-harvesting systems, ensuring good power transfer from the antenna to the rectifier is a critical design objective. The impedance matching circuit (IMC) plays a fundamental role in this context, as it is placed between the receiving antenna and the rectifier to maximize power transfer by ensuring proper impedance alignment. Without an IMC, a significant portion of the captured RF energy may be lost due to impedance mismatch [

3]. Typically, antennas are designed with a fixed impedance, often standardized at 50 Ω [

21], whereas the impedance of rectifier circuits varies with frequency and depends on the characteristics of the rectifying components. This mismatch necessitates the use of an IMC to ensure efficient power transfer. The performance of an IMC is commonly evaluated using the reflection coefficient (

), which quantifies the amount of power reflected back to the source due to impedance mismatch. A practical design criterion requires

to be lower than −10 dB [

4], indicating that nearly 90% of the incident power is effectively transferred to the load.

An IMC may adopt various topologies, such as L, T, or

, the L-topology is commonly preferred for its simplicity, compactness, and ease of implementation [

12]. In contrast, T,

, and hybrid configurations often offer improved impedance matching, but at the cost of an increased circuit area and greater design complexity. In terms of implementation, two main design approaches are frequently employed: lumped-element (LC) circuits and distributed transmission line (TL) structures [

23]. LC-based designs, which use inductors and capacitors, are valued for their simplicity and ease of implementation, making them ideal for ultra-compact or implantable RF-energy-harvesting systems. In ref. [

12], an L-topology is employed, consisting of a series inductor and a parallel capacitor, achieving an excellent reflection coefficient of −28.7 dB at 2.45 GHz, indicating highly effective impedance matching. The TL-based approach relies on distributed transmission line structures, incorporating open, short, radial, or meandered stubs printed directly onto the substrate. These structures enable more effective multiband tuning, particularly in space-rich environments where substrate area is less constrained. The study in ref. [

8] presents a multiband TL-based IMC, employing transmission lines with radial stubs to achieve effective matching at frequencies of 1.8, 2.1, 2.4, 2.65, and 3.5 GHz, each with reflection coefficients lower than −15 dB, demonstrating both flexibility and multiband capability. Hybrid IMCs combine LC and TL techniques to improve impedance matching while also simplifying rectifier integration and reducing overall cost. Ref. [

24] introduces a hybrid T-topology using inductors and radial stubs (as substitutes for capacitors), achieving reflection coefficients below −25 dB at 0.95 and 9.25 GHz simultaneously.

Table 2 summarizes representative IMC designs, detailing their operating frequencies, circuit types, and corresponding

values.

Beyond conventional architectures, recent approaches exploit metamaterials to improve both compactness and multiband performance. As shown in ref. [

17], integrating an MTM-EBG (Metamaterial Electromagnetic Bandgap) unit cell into a microstrip line enables independent tuning of the stub’s electrical length at each frequency. This technique supports the design of compact, multiband matching networks, well suited for wideband RF energy harvesting in space-constrained applications, while also simplifying optimization and lowering manufacturing costs.

The design of impedance matching circuits (IMCs) must address both reflection loss minimization and the physical constraints of RFEH applications. LC-based networks are compact and easy to implement, ideal for implantable or miniaturized systems, while TL-based designs support multiband operation but require more space. Hybrid LC-TL approaches offer a balance between flexibility and complexity. The shift toward metamaterial-inspired topologies reflects the need for broadband, efficient, and integration-friendly solutions in next-generation RFEH systems.

3.3. RF-DC Rectifier for RFEH

The rectifier is a key component in RF-energy-harvesting (RFEH) systems, responsible for converting the captured RF signal into usable DC energy. Its design directly impacts the overall efficiency of the energy-harvesting system, and various topologies have been proposed to address different constraints, such as input power level, load conditions, and circuit complexity. Rectifier circuits are classified into half-wave and full-wave types with various topologies.

Table 3 summarizes the main rectifier configurations, including diode types, achieved power conversion efficiency (PCE), load resistance, and output voltage. Half-wave rectifiers use a single diode and rectify only one half of the AC signal, resulting in limited efficiency. Despite this, half-wave rectifiers remain attractive for low-power, cost-sensitive, and space-constrained applications due to their simplicity, low component count, and minimal fabrication cost. For instance, the half-wave rectifier proposed in [

20] achieved a PCE of only 31.22% under a 2 kΩ load at an input power of −12 dBm per rectenna (RA + IMC + rectifier) within a compact area of 67 mm × 27 mm.

In contrast, full-wave rectifiers such as voltage doublers, Dickson multipliers, and Cockcroft–Walton architectures are preferred in scenarios where higher output voltage is required. While they require more components and occupy greater circuit area, these designs convert the entire AC signal into DC, thereby significantly enhancing energy conversion efficiency. Voltage doublers are widely employed in RF energy harvesting (RFEH) due to their simplicity and higher output voltages. The work in ref. [

9] utilized a voltage doubler rectifier, achieving a PCE of 65% and 3.2 V under a 2 kΩ load. Similarly, study ref. [

24] reported a PCE of 69% and an output voltage of 2.33 V at −2.5 dBm input power across a 14 kΩ load. Multi-stage rectifiers are intended to enhance output voltage under low-input-power conditions. Nonetheless, their adoption is often limited by increased circuit complexity and the cumulative losses associated with cascading multiple stages, which can outweigh the benefits in ultra-low-power RF-harvesting scenarios [

1]. These architectures are better suited for environments where ambient RF power levels are relatively high or where energy accumulation over time is feasible, such as near dedicated transmitters or in RF-dense urban areas. A seven-stage Cockcroft–Walton rectifier implemented in ref. [

10] achieved a peak power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 56% at an input power of −1 dBm while providing a maximum output voltage of 3.18 V at 0 dBm across a 50 kΩ load. Meanwhile, a ten-stage Cockcroft–Walton rectifier reported in ref. [

19] achieved 50.38% efficiency at 5.59 dBm input power, producing 3.8 V and reaching up to 14.76 V at 14.22 dBm within an antenna array system across a 21 kΩ load. Other full-wave rectifier architectures also aim to optimize energy conversion efficiency despite higher load resistances. For example, a multistage Dickson rectifier in ref. [

3] achieved a PCE of 73.46% under a 500

and 49.12% across a 1 MΩ, providing 2.99 V.

Most rectifiers reported in the literature [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] utilize Schottky diodes due to their low forward voltage, low series resistance, and minimal parasitic capacitance, making them ideal for low-power and high-frequency applications [

3,

10,

12,

13,

24].

The rectifier design must balance simplicity, output voltage, and efficiency across input power levels. Single-diode and voltage doubler circuits are suitable for low-power or space-constrained applications, while multi-stage topologies like Cockcroft–Walton or Dickson offer higher voltages at the cost of complexity and size. The number of stages, diode type, and topology must align with ambient power density, load demands, and integration constraints. Wearable systems benefit from compact designs, whereas IoT nodes can support more elaborate rectifiers with energy storage.

3.4. System-Level Trade-Offs and Experimental Use Cases

Designing an efficient RF-energy-harvesting (RFEH) system requires careful optimization and coherent integration of its key subsystems: RA, IMC, and rectifier. Trade-offs emerge when reconciling electrical efficiency with mechanical and application-specific constraints. For wearable or implantable use, compactness and flexibility are critical, yet often reduce antenna gain and matching bandwidth, while stationary IoT deployments allow for larger structures and advanced rectification, at the cost of increased complexity and footprint. Several experimental studies highlight these trade-offs in practice.

Study ref. [

10] designed a textile-based metasurface patch antenna (70 × 70 mm) integrated with a seven-stage Cockcroft–Walton rectifier. Tested under free space, on-body, and real Wi-Fi conditions, the system achieved a 450 μW DC output at −1 dBm input (56% PCE), reduced to 46% on-body. Although mechanically compliant, the felt substrate introduced RF losses, requiring a larger antenna and rectifier, limiting the compactness. Similarly, ref. [

11] built a flexible rectenna operating at 915 MHz for ultra-low-power harvesting (0.17 μW/cm

2). Integrated with a DC-DC boost converter, it delivered 1 V to power a BLE sensor 11 m from a Powercast source. The design balanced surface size, impedance tuning, and orientation tolerance. In more robust ambient scenarios, ref. [

6] proposed a quasi-isotropic harvester using orthogonally polarized antennas on FR4 to simultaneously collect UHF-TV and FM energy. With dual-stage matching and rectifiers, it harvested 885 μW (FM) and 231 μW (TV), powering a BLE node for 16 min after 26 min of charging. The spatial coverage came with greater circuit complexity and system volume. Finally, ref. [

1] presented a compact bow-tie antenna (0.85–3.66 GHz) integrated with a voltage doubler rectifier and a PMU, fully embedded beneath the ground plane. Real-world outdoor tests on the KAIST campus under ambient RF conditions confirmed broadband impedance matching and a system-level efficiency of 12.46% at −12.98 dBm input. However, cutting the antenna for miniaturization degraded impedance matching, which was later recovered via LC tuning.

Collectively, these examples demonstrate how RFEH systems must be tailored through careful trade-offs between form factor, power levels, antenna structure, and integration strategy depending on the intended deployment context.

4. Challenges and Perspectives

Although radio frequency energy harvesting (RFEH) has experienced significant progress in recent years, several critical challenges still limit its widespread deployment. A primary constraint is the inherently low power density of ambient RF sources, necessitating rigorous optimization across the entire energy conversion chain, from the antenna to the rectifier. On the receiving side, the antenna plays a key role in capturing ambient RF energy. However, designing antennas that simultaneously achieve high gain, multiband or wideband operation, circular polarization, and compact size remains particularly challenging, especially for wearable or implantable applications. To overcome these constraints, various antenna solutions have been proposed in the literature, including slotted structures, optimized low-loss materials, and metamaterial-based designs. While these approaches offer improved performance, they often result in increased design complexity and higher fabrication costs. Impedance matching circuits (IMCs) must efficiently manage power transfer under varying frequency and load conditions. Lumped element (LC-based) circuits offer simplicity and ease of integration, whereas distributed transmission line (TL-based) solutions, compatible with printed circuit fabrication, typically suffer from increased complexity, larger physical size, and limited tunability. Emerging hybrid designs and metamaterial-inspired architectures offer valuable trade-offs but are still at an early developmental stage. Downstream, rectifier circuits represent another major bottleneck. Multi-stage architectures, such as voltage doublers, Dickson, or Cockcroft–Walton multipliers, can achieve higher output voltages, but they typically exhibit reduced efficiency in complex configurations or at low-input RF power levels. Effective integration with energy storage elements, including micro-batteries or supercapacitors, remains essential to maintain stable operation under fluctuating ambient conditions. At the same time, miniaturization remains crucial for the seamless integration of RFEH systems into next-generation devices. Advances in manufacturing technologies, such as flexible substrates, 3D printing, and novel functional materials, offer promising avenues toward achieving compact and lightweight designs, though challenges related to cost-effectiveness and scalability persist.

Furthermore, incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) into RFEH systems opens promising avenues for adaptive performance optimization. AI-based algorithms can dynamically reconfigure antenna parameters, such as resonance frequency and radiation pattern, to harvest energy more efficiently from dominant ambient sources. Machine learning models may also adjust impedance matching circuits in real time, compensating for frequency drifts or environmental changes. In addition, intelligent rectifier control allows the system to switch between modes depending on signal strength or waveform characteristics. These AI-driven strategies enable real-time adaptability without hardware reconfiguration, thereby improving efficiency. As such, environment-aware learning and self-tuning mechanisms represent a robust path toward intelligent, resilient RF energy harvesting.

Finally, ensuring robustness in real-world applications demands consideration of environmental resilience, particularly regarding interference, multipath propagation effects, and extreme temperature variations. Addressing these challenges will require interdisciplinary collaboration, integrating advances in materials science, RF design, microelectronics, energy management, and AI-driven control strategies. Given the rapid growth of IoT applications, autonomous sensors, and biomedical electronics, RFEH technology is strategically positioned to provide sustainable, autonomous, and intelligent power solutions for future connected ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review has outlined recent advancements in RF-energy-harvesting (RFEH) architectures, focusing on receiving antennas, impedance matching circuits, and RF-to-DC rectifiers for low-power and implantable applications. Significant progress has been achieved in terms of miniaturization, gain improvement, and conversion efficiency. Advanced antenna materials and configurations offer a good balance between compactness and performance, while hybrid and metamaterial-based matching circuits address multiband and size limitations. Despite these advances, the rectifier efficiency remains constrained by trade-offs linked to circuit complexity and low input power, with Schottky diodes playing a central role in high-frequency conversion. Major challenges persist, including low ambient RF power density, integration complexity, and environmental variability. To address these, future research should adopt interdisciplinary strategies combining materials science, microelectronics, RF design, and AI-based optimization. Intelligent, adaptive systems for dynamic tuning and real-time control will be key to making RFEH a viable, autonomous, and sustainable energy solution for next-generation IoT and biomedical technologies.