1. Introduction

A study by the University of Pretoria Veterinary Sciences developed a mathematical model between the L*a*b* colour of blood and blood oxygen saturation content [

1]. L*a*b* colourimeters, such as the Lovibond, are bulky and require a substantial sample. Motivated by that work, this paper develops a miniaturised L*a*b* colour sensor. This sensor can output L*a*b* colour through medical tubing. The projected goal outside the scope of this paper is to use the L*a*b* colour space, with the model from [

1], to estimate blood oxygen levels. These levels, combined with the partial pressure of oxygen (pO

2), will ultimately aid diagnosis by comparison with a standard oxygen dissociation curve [

2]. Measuring unusual temperature and pH offers insights into shifts in the oxygen dissociation curve. Such shifts reflect changes in haemoglobin’s oxygen affinity. Temperature and pH are also useful for compensation in electrochemical measurements. The aim of this work is to design a low-power, miniaturised, multi-sensing prototype sensor. The preliminary sensor array measures dissolved oxygen content and the L*a*b* colour of a dyed sample. Dissolved oxygen content was varied using sodium sulphite. Temperature and pH sensors were included for the additional insights listed above.

2. Materials and Methods

The sensor array employs two analytical methods: electrochemistry and optics.

2.1. Dissolved Oxygen

For the measurement of dissolved oxygen, a screen-printed electrode (Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland), consisting of a gold working electrode, silver/silver chloride reference electrode and carbon counter electrode. A potentiostat (DropSens S.L., Llanera, Asturias, Spain) was used to perform linear sweep voltammetry in varying concentrations of sodium sulphite, which is known to be an oxygen scavenger. A polarising voltage of 0.9 V was found to be appropriate for amperometry and hence was selected for the custom-designed potentiostat. The potentiostat design incorporated elements from [

3,

4], such as the inclusion of a control amplifier, buffer and a transimpedance amplifier. The current generated through amperometry was converted into a voltage through a transimpedance amplifier. The voltage output was then read by the ADC of a microcontroller. The Black Pill STM32F411CEU6 development board (using STM32F411CEU6 MCU from STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) was selected as the microcontroller due to its small size and ability to allow calibration of the sensor.

2.2. L*a*b* Colour

For the measurement of the redness of a liquid, in comparison to the redness of blood, an RGB sensor (Adafruit Industries LLC, New York, NY, USA) was purchased. This consisted of the TCS34725 light-to-digital converter that makes use of I

2C. The model developed by the UP Veterinary campus in [

1] made use of the L*a*b* colour space; hence, a conversion between the RGB colours space, to the L*a*b* colour space in software was necessary. The mathematical conversion from [

5] was programmed in C for the same microcontroller selected above due to its ability to perform the real-time conversion. An RGB LED (OSRAM Opto Semiconductors GmbH, Regensburg, Germany) was also purchased to develop a light source as close as possible to D65 by varying the amount of current on the respective R, G and B LEDs through varying resistor values. The Avantes spectrometer (Avantes B.V., Apeldoorn, Netherlands) and the halogen light source (Avantes B.V., Apeldoorn, Netherlands) were used for verification. A commercial red food colourant (Robertsons, Unilever South Africa (Pty) Ltd, Durban, South Africa) was used as the dye source added to distilled water in various quantities to vary the redness of the liquid.

2.3. Temperature and pH

For the pH and temperature measurement, a screen-printed electrode from Metrohm that consisted of a hydrogen-sensitive ruthenium oxide working electrode, silver/silver chloride reference electrode and carbon counter electrode was utilised. A Dropsens potentiostat was used to measure the open circuit potential of the reference and working electrode. An RTD (RS Components, South Africa) in conjunction with a transducer bridge was used to measure the temperature. A sampling chamber was 3D printed using the resin printer (Formlabs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA) in clear resin to house the electrodes and enable movement of the liquid onto the electrodes. A colour sensor housing was 3D printed in black resin from Formlabs to enable optical measurements through medical tubing. An OLED display (Midas Displays, Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK) was added to display all the modalities available.

Figure 1 shows the full system.

2.4. Data Collection

The sample consisted of distilled water mixed with varying amounts of sodium sulphite. The dissolved oxygen concentration was determined using stoichiometric calculations based on the known quantities of reagents. To create samples with different colour intensities, varying amounts of red food colouring were added. Each sample was first measured using laboratory equipment and then tested with the prototype sensor. The liquid was pumped through medical tubing, where the prototype measured colour intensity, dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature before the sample was discharged into a waste beaker. The tubing, sampling chamber, and electrodes were rinsed and dried between readings. The entire process took approximately 20 min, with a 3 h interval between the first and last measurements.

3. Results

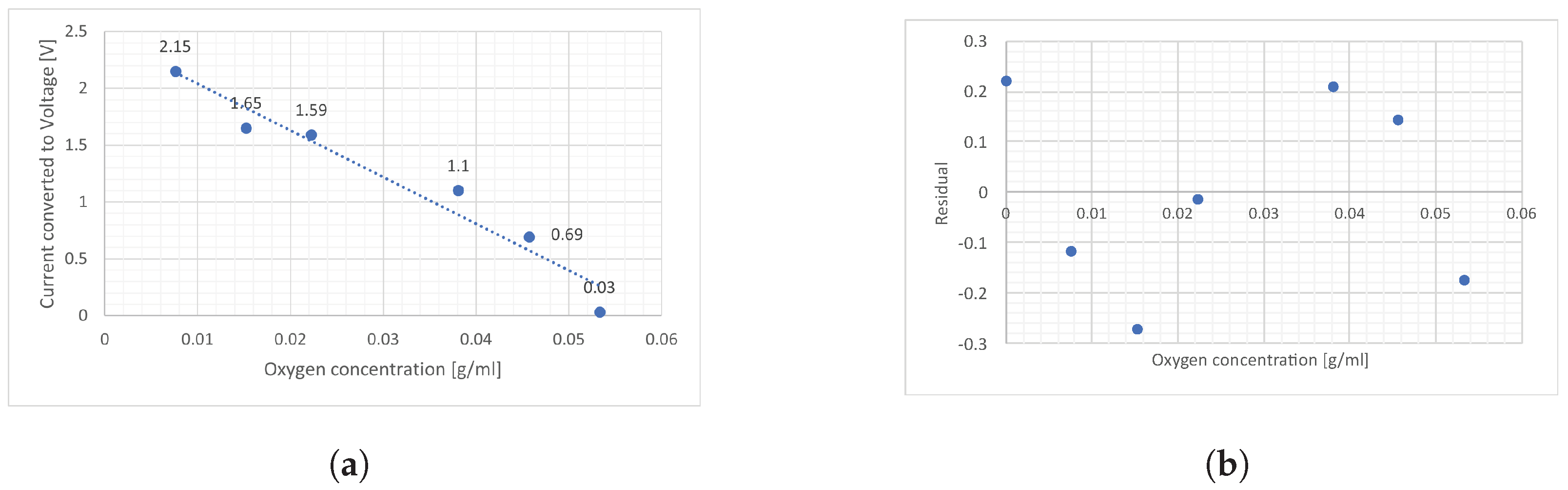

A calibration curve of partial pressure against voltage (induced by current) was derived. A linear model has been applied, as seen in

Figure 2a. A residual plot in

Figure 2b is computed by comparing the measured voltage points to the fitted trend.

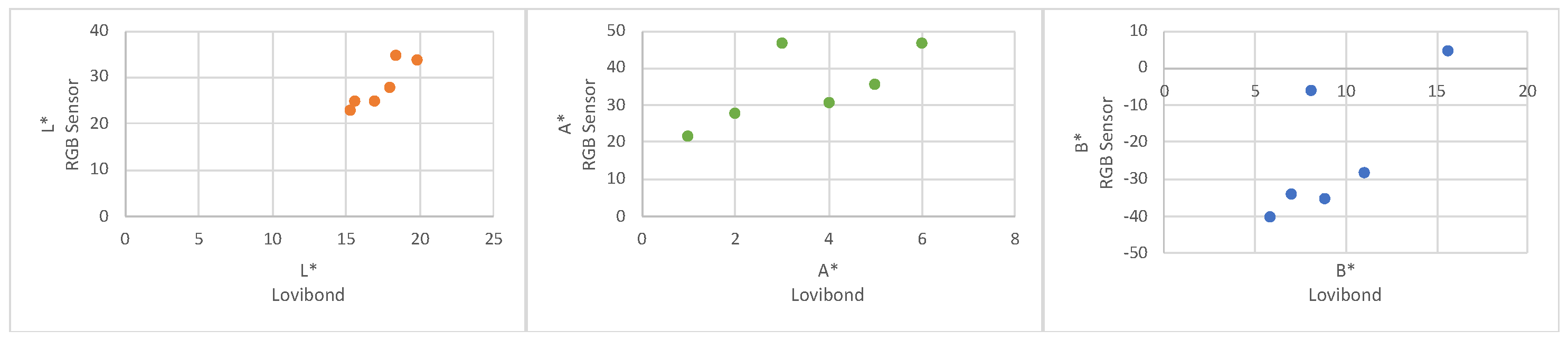

The RGB sensor after processing to L*a*b* is compared to an Avantes spectrometre, the two values are computed against each other, as seen in

Figure 3, to see how well the sensor compared to an industrial standard, similar to the electrochemical measurement. The average absolute residuals are provided in the form of mean ± standard deviation of the mean. L* was founded to be 11.0 ± 3.27 %, A* was found to be 11.3 ± 6.60 and B* was found to be 32.38 ± 14.35.

The pH and temperature sensors were validated against a laboratory pH metre and thermometer, respectively. The pH sensor had a mean absolute difference of 0.38 ± 0.30, while the temperature sensor showed a mean absolute difference of 0.17 ± 0.10, both expressed as percentages of the measured values. The multimodal device operated reliably on a 5 V power bank and weighed less than 130 g, including all integrated sensors.

4. Discussion

The amount of sodium sulphite added to 10 mL of distilled water ranged from 0.6 to 3 g, yielding a maximum pH of 8. This value lies outside the range reported in [

6], suggesting that the sulphite ions were not oxidised and that the dissolved oxygen content remained unaffected. For dissolved oxygen determination, the applied linear model produced low residuals, and the distinct voltage responses for different concentrations demonstrate the sensor’s potential for oxygen sensing in blood. The low residuals further confirm a well-fitted trend. However, a dedicated study with a larger sample size would be necessary to validate the device’s applicability. Since distilled water lacks the ionic composition of blood, incorporating relevant ions in future tests would provide a more accurate evaluation of the sensor’s performance.

The laboratory sensor consistently overestimated L* and a* values while underestimating b*. These discrepancies may result from differences in illumination, as the spectrometer comparator employed a halogen light source, whereas a different source was used during testing. Further investigation into the effect of the light source could help quantify this bias and enhance sensor accuracy, including through measurement of a control state. Despite these variations, the absolute differences observed—relative to the bounded ranges of the colour parameters (L*: 100, a*, b*: 255)—indicate strong potential for the intended application.

The temperature and pH sensors also demonstrated reliable performance, showing deviations of less than 0.5 units compared to the laboratory thermometer and pH metre.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a strong proof of concept for the biosensor. With the proposed improvements, a larger sample set, and dedicated blood sample testing, the work could evolve into a highly promising and practical biosensing platform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M. and T.-H.J.; methodology, K.M.; software, K.M.; validation, K.M.; formal analysis, K.M.; investigation, K.M.; resources, T.-H.J.; data curation, K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.; writing—review and editing, K.M.; visualisation, K.M.; supervision, T.-H.J.; project administration, T.-H.J.; funding acquisition, T.-H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the South African Department of Science and Innovation Nano and Micro Manufacturing Facility grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data for L*a*b* and concentration are included in this article. For the pH and temperature, only summarized data (mean ± standard deviation) are reported. Additional raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Basson, E.P.; Zeiler, G.E.; Kamerman, P.R.; Meyer, L.C. Use of blood colour for assessment of arterial oxygen saturation in immobilized impala (Aepyceros melampus). Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2021, 48, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, R.N. Regulation of Tissue Oxygenation, 2nd ed.; Colloquium Series on Integrated Systems Physiology: From Molecule to Function; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Umar, S.N.H.; Bakar, E.A.; Kamaruddin, N.M.; Uchiyama, N. A low cost potentiostat device for monitoring aqueous solution. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 217, 04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snizhko, D.; Zholudov, Y.; Kukoba, A.; Xu, G. Potentiostat design keys for analytical applications. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 936, 117380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, K.; Mery, D.; Pedreschi, F.; León, J. Color measurement in L*a*b* units from RGB digital images. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinsky, A.G. Features of Sulphite Oxidation on Gold Anode. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 188, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).