Amino Acid 1,2,4-Triazole Mimetics as Building Blocks of Peptides †

Abstract

1. Introduction

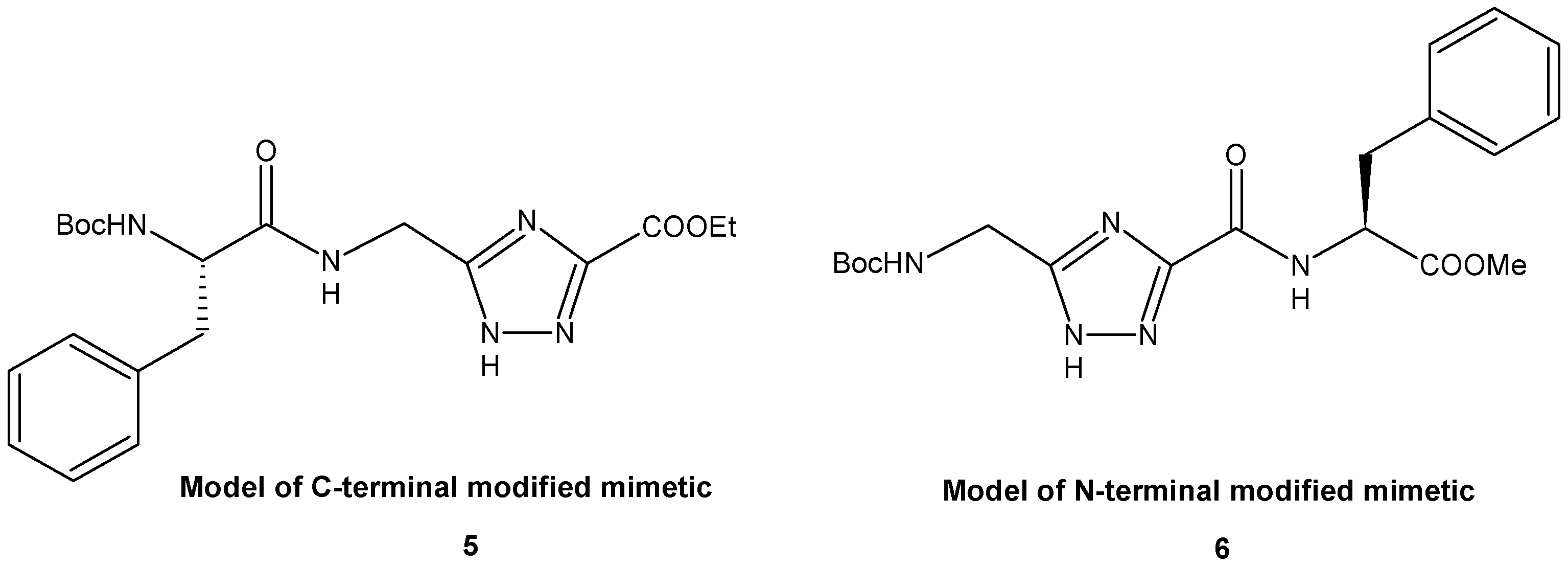

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis

4.3. Antibacterial Activity

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.L.; Dunn, M.K. Therapeutic peptides: Historical perspectives, current development trends, and future directions. Bioorganic. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 2700–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muttenthaler, M.; King, G.F.; Adams, D.J.; Alewood, P.F. Trends in peptide drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetse, J.; Kandel, S.; Mamani, U.F.; Cheng, K. Recent advances in the development of therapeutic peptides. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, H.L.; Yamamoto, A. Penetration and enzymatic barriers to peptide and protein absorption. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1990, 4, 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bocci, V. Catabolism of therapeutic proteins and peptides with implications for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1990, 4, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.M.; Cabalteja, C.C.; Horne, W.S. Peptide Backbone Composition and Protease Susceptibility: Impact of Modification Type, Position, and Tandem Substitution. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.; Moore, S.; Mayes, J.; Parkin, E.; Beeg, M.; Canovi, M.; Gobbi, M.; Mann, D.M.A.; Allsop, D. Development of a Proteolytically Stable Retro-Inverso Peptide Inhibitor of β-Amyloid Oligomerization as a Potential Novel Treatmen for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 3261–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diness, F.; Schoffelen, S.; Meldal, M. Advances In Merging Triazoles with Peptides and Proteins; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Recnik, L.; Kandioller, W.; Mindt, T.L. 1,4-Disubstituted 1,2,3-Triazoles as Amide Bond Surrogates for the Stabilisation of Linear Peptides with Biological Activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonandi, E.; Christodoulou, M.S.; Fumagalli, G.; Perdicchia, D.; Rastelli, G.; Passarella, D. The 1,2,3-triazole ring as a bioisostere in medicinal chemistry. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 1572–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valverde, I.E.; Mindt, T.L. 1,2,3-Triazoles as Amide-bond Surrogatesin Peptidomimetics. Chimia 2013, 67, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kann, N.; Johansson, J.R.; Beke-Somfai, T. Conformational properties of 1,4- and 1,5-substituted 1,2,3-triazole amino acids—Building units for peptidic foldamers. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesar, J.; Sollner, M. Use of 3,5-Disubstituted 1,2,4-Triazoles for the Synthesis of Peptidomimetics. ChemInform 2000, 30, 4147–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dost, J.; Stem, J.; Heschel, M. Zur herstellung von 5-substitmerten 1,2,4-trtazol-3-carbonsaurederivaten aus oxalsaureethylester-N1-acylamtdrazonen. Z. Chem. 1986, 26, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S.; Estenne-Bouhtou, G.; Luthman, K.; Csoregh, I.; Hesselink, W.; Hacksell, U. Synthesis of 1, 2, 4-Oxadiazole-, 1, 3, 4-Oxadiazole-, and 1, 2, 4-Triazole-Derived Dipeptidomimetics. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 3112–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleynik, E.S.; Shmarina, A.A.; Mitina, E.R.; Mikhina, E.A.; Semenov, I.A.; Savina, E.D.; Grebenkina, L.E.; Zhidkova, E.M.; Lesovaya, E.A.; Vetrova, E.N.; et al. 5-Amino-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide homologues and their biological potential. Mendeleev. Commun. 2025, 35, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oleynik, E.; Dmitrieva, V.; Shmarina, A.; Mikhina, E.; Grebenkina, L.; Mitina, E.; Sineva, O.; Matveev, A. Amino Acid 1,2,4-Triazole Mimetics as Building Blocks of Peptides. Chem. Proc. 2025, 18, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26739

Oleynik E, Dmitrieva V, Shmarina A, Mikhina E, Grebenkina L, Mitina E, Sineva O, Matveev A. Amino Acid 1,2,4-Triazole Mimetics as Building Blocks of Peptides. Chemistry Proceedings. 2025; 18(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26739

Chicago/Turabian StyleOleynik, Evgenia, Vera Dmitrieva, Anna Shmarina, Ekaterina Mikhina, Lyubov Grebenkina, Ekaterina Mitina, Olga Sineva, and Andrey Matveev. 2025. "Amino Acid 1,2,4-Triazole Mimetics as Building Blocks of Peptides" Chemistry Proceedings 18, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26739

APA StyleOleynik, E., Dmitrieva, V., Shmarina, A., Mikhina, E., Grebenkina, L., Mitina, E., Sineva, O., & Matveev, A. (2025). Amino Acid 1,2,4-Triazole Mimetics as Building Blocks of Peptides. Chemistry Proceedings, 18(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26739